Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

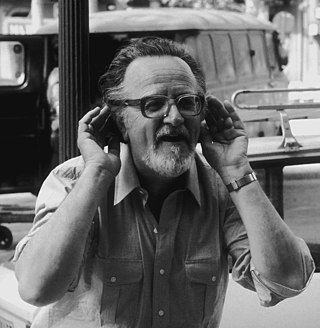

José Donoso

Chilean writer, journalist and professor (1924 – 1996) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

José Manuel Donoso Yáñez (5 October 1924 – 7 December 1996), known as José Donoso, was a Chilean writer, journalist and professor. He lived most of his life in Chile, although he spent many years in self-imposed exile in Mexico, the United States and Spain. Although he stated that he had left Chile in the 1960s for personal reasons, after 1973 his exile was also a form of protest against the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. He returned to Chile in 1981 and lived there until his death in 1996.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

Donoso is the author of a number of short stories and novels, which contributed greatly to the Latin American literary boom. His best known works include the novels Coronation, Hell Has No Limits (El lugar sin límites), and The Obscene Bird of Night (El obsceno pájaro de la noche). His works are known for their dark sense of humor and themes including sexuality, the duplicity of identity, and psychology.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Donoso was born in Santiago to the physician José Donoso Donoso and Alicia Yáñez. Alicia was the niece of Eliodoro Yáñez.[citation needed]

Donoso studied at The Grange School, where he was classmates with Luis Alberto Heiremans and Carlos Fuentes, and later studied in Liceo José Victorino Lastarria High School. During his childhood, Donoso worked as a juggler and an office worker. Later he would begin working as a writer and teacher.[citation needed]

In 1945 he traveled to the southernmost parts of Chile and Argentina, where he worked on sheep farms in the province of Magallanes. Two years later, he finished high school and signed up to study English at the Institute of Teaching in the Universidad de Chile. In 1949, thanks to a scholarship from the Doherty Foundation, he went to study English literature at Princeton University, where he studied under such professors such as R. P. Blackmur, Lawrence Thompson and Allan Tate. The Princeton magazine, MSS, published his first two stories, both written in English: "The Blue Woman" (1950) and "The Poisoned Pastries" (1951).[1] Donoso graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in English from Princeton in 1951 after completing a senior thesis titled "The Elegance of Mind of Jane Austen: An Interpretation of Her Novels Through the Attitudes of Heroines."[2]

Remove ads

Career

Summarize

Perspective

In 1951, he traveled to Mexico and Central America. He then returned to Chile and in 1954 started teaching English at the Universidad Católica and in the Kent School.

His first book, Summer Vacation and Other Stories (Veraneo y otros cuentos), was published in 1955 and won the Municipal Prize of Santiago. In 1957, while he lived with a family of fishermen in the Isla Negra, he published his first novel, Coronación (Coronation), in which he described the high Santiaguina classes and their decadence. Eight years later, it was translated and published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf and in England by The Bodley Head.

In 1958, he left Chile for Buenos Aires and returned to Chile in 1960.[3]

He started writing for the magazine Revista Ercilla in 1959 and filed stories while traveling through Europe. He continued as an editor and literary critic for Ercilla until 1964. He also worked as a co-editor of the Mexican journal Siempre.[4][5]

In 1961, he married the painter, writer and translator María del Pilar Serrano (1925–1997), also known as María Esther Serrano Mendieta, daughter of Juan Enrique Serrano Pellé from Chile and Graciela Mendieta Alvarez from Bolivia. Donoso had previously met her in Buenos Aires.[3]

The pair left Chile in 1965 for Mexico. Donoso would work as a writer-in-residence at the University of Iowa from 1965 to 1967. He and his wife moved to Spain in 1967.[3][1] In 1968, the couple adopted a three-month-old girl from Madrid, whom they named María del Pilar Donoso Serrano, best known as Pilar Donoso.[6]

Donoso taught a workshop in writing novels in the Comparative Literature Department at Dartmouth College during the 1975 Summer Term.

In 1981, after his return to Chile, he conducted a literature workshop in the which, during the first period, many writers such as Roberto Brodsky, Marco Antonio de la Parra, Carlos Franz, Carlos Iturra, Eduardo Llanos, Marcelo Maturana, Sonia Montecino Aguirre, Darío Oses, Roberto Rivera, Jaime Collyer, Gonzalo Contreras, and Jorge Marchant Lazcano participated. Later, Arturo Fontaine Talavera, Alberto Fuguet and Ágata Gligo attended, among others.

At the same time, he continued publishing novels, even though they did not reach the same level of acclaim as his preceding works:[citation needed] Curfew (La desesperanza), the novellas Taratuta, Still Life with Pipe (Naturaleza muerta con cachimba), and Donde van a morir los elefantes (1995). El mocho (1997) and The Lizard's Tale (Lagartija sin cola) were published posthumously.

Remove ads

Death

José Donoso died of liver cancer in his house in Santiago, 7 December 1996 at the age of 72.[7] On his deathbed, according to popular belief, he asked that his family read him the poems of Altazor by Vicente Huidobro. His remains were buried in the cemetery of a spa located in the province of Petorca, 80 kilometers from Valparaíso.[8]

In 2009, his daughter, Pilar Donoso, published a biography of her father titled Correr el tupido velo (Drawing the Veil), based on her father's private diaries, notes and letters, as well as Pilar's own memories.[9]

Awards and honors

- 1956: Premio Municipal de Santiago

- 1962: William Faulkner Foundation Prize for Latin American Literature

- 1969: Premio Pedro de Oña (Spain)

- 1978: Premio de la Crítica de narrativa castellana (Spain)

- 1990: Premio Mondello (Italy)

- 1990: Premio Nacional de Literatura en Chile

- 1991: Prix Roger Caillois (France)

- 1995: Caballero Gran Cruz de la Orden del Mérito Civil (Spain)

Bibliography

Novels

- Coronación (Nascimento, 1957). Coronation, translated by Jocasta Goodwin (The Bodley Head; Knopf, 1965).

- Este domingo (Zig-Zag, 1966). This Sunday, translated by Lorraine O'Grady Freeman (Knopf, 1967).

- El lugar sin límites (1966). Hell Has No Limits, translated by Suzanne Jill Levine in Triple Cross (Dutton, 1972) and later as a revised translation (Sun & Moon Press, 1995).

- El obsceno pájaro de la noche (Seix Barral, 1970). The Obscene Bird of Night, translated by Hardie St. Martin and Leonard Mades (Knopf, 1973). Revised by Megan McDowell (New Directions, 2024).

- Casa de campo (Seix Barral, 1978). A House in the Country, translated by David Pritchard and Suzanne Jill Levine (Knopf, 1984).

- La misteriosa desaparición de la marquesita de Loria (1981). The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria, trans. Megan McDowell (New Directions, 2025).

- El jardín de al lado (1981). The Garden Next Door, translated by Hardie St. Martin (Grove, 1992).

- La desesperanza (Seix Barral, 1986). Curfew, translated by Alfred MacAdam (George Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988).

- Donde van a morir los elefantes (1995). Where the Elephants Will Die.

- El mocho (posthumous, 1997). The Mocho.

- Lagartija sin cola (posthumous, 2007). The Lizard's Tale, edited by Julio Ortega and translated by Suzanne Jill Levine (Northwestern University Press, 2011).

Novellas

- Tres novelitas burguesas (Seix Barral, 1973). Sacred Families: Three Novellas, translated by Andrée Conrad (Knopf, 1977; Gollancz, 1978).

- Contains: Chatanooga choochoo (Chattanooga Choo-Choo), Átomo verde número cinco (Green Atom Number Five) and Gaspard de la Nuit.

- Cuatro para Delfina (Seix Barral, 1982).

- Contains: Sueños de mala muerte, Los habitantes de una ruina inconclusa, El tiempo perdido and Jolie Madame

- Taratuta y Naturaleza muerta con cachimba (Mondadori, 1990). Taratuta and Still Life with Pipe, translated by Gregory Rabassa (W. W. Norton, 1993).

- Nueve novelas breves (Alfaguara, 1996).

- Compiles Tres novelitas burguesas, Cuatro para Delfina and Taratuta y Naturaleza muerta con cachimba

Short story collections

- Veraneo y otros cuentos (1955). Summertime and Other Stories.

- Contains seven stories: "Veraneo" ("Summertime"), "Tocayos" ("Namesakes"), "El Güero" ("The Güero"), "Una señora" ("A Lady"), "Fiesta en grande" ("Big Party"), "Dos cartas" ("Two Letters") and "Dinamarquero" ("The Dane's Place").

- Republished as Veraneo y sus mejores cuentos (Zig-Zag, 1985), with three additional stories: "Paseo", "El hombrecito" and "Santelices".

- El charleston (1960).

- Contains five stories: "El charleston" ("Charleston"), "La puerta cerrada" ("The Closed Door"), "Ana María", "Paseo" ("The Walk") and "El hombrecito" ("The Little Man").

- Los mejores cuentos de José Donoso (Zig-Zag, 1966). The Best Stories of José Donoso. Selection by Luis Domínguez.

- Contains: "Veraneo", "Tocayos", "El Güero", "Una señora", "Fiesta en grande", "Dos cartas", "Dinamarquero", "El charleston", "La puerta cerrada", "Ana María", "Paseo", "El hombrecito", "China" and "Santelices".

- Republished as Cuentos (Seix Barral, 1973; Alfaguara, 1998; Penguin, 2015).

- Charleston and Other Stories, translated by Andrée Conrad (Godine, 1977).

- Contains nine stories from Cuentos: "Ana María", "Summertime", "The Güero", "A Lady", "The Walk", "The Closed Door", "The Dane's Place", "Charleston" and "Santelices".

Poems

- Poemas de un novelista (1981)

Other

- Historia personal del "boom" (1972). The Boom in Spanish American Literature: A Personal History, translated by Gregory Kolovakos (1977).

- Artículos de incierta necesidad (1998). Selection of his articles published for magazines compiled by Cecilia García-Huidobro.

- Conjeturas sobre la memoria de mi tribu (fictional memories, 1996). Conjectures About the Memory of My Tribe.

- Diarios tempranos. Donoso in progress, 1950-1965 (2016)

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads