Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Bat

Order of flying mammals From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Bats (order Chiroptera /kaɪˈrɒptərə/) are winged mammals; the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most birds, flying with their long spread-out digits covered with a thin membrane or patagium. The smallest bat, and one of the smallest extant mammals, is Kitti's hog-nosed bat, which is 29–33 mm (1.1–1.3 in) in length, 150 mm (5.9 in) across the forearm and 2 g (0.071 oz) in mass. The largest bats are the flying foxes, with the giant golden-crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus) reaching a weight of 1.5 kg (3.3 lb) and having a wingspan of 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in).

The second largest order of mammals after rodents, bats comprise about 20% of all classified mammal species worldwide, with at least 1,500 known species. These were traditionally divided into two suborders: the largely fruit-eating megabats, and the echolocating microbats. But more recent evidence has supported dividing the order into Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera, with megabats as members of the former along with several species of microbats. Many bats are insectivores, and most of the rest are frugivores (fruit-eaters) or nectarivores (nectar-eaters). A few species feed on animals other than insects; for example, the vampire bats are haematophagous (feeding on blood). Most bats are nocturnal, and many roost in caves or other refuges; it is uncertain whether bats have these behaviours to escape predators. Bats are distributed globally in all except the coldest regions. They are important in their ecosystems for pollinating flowers and dispersing seeds as well as controlling insect populations.

Bats provide humans with some direct benefits, at the cost of some disadvantages. Bat dung has been mined as guano from caves and used as fertiliser. Bats consume insect pests, reducing the need for pesticides and other insect management measures. Some bats are also predators of mosquitoes, suppressing the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases. Bats are sometimes numerous enough and close enough to human settlements to serve as tourist attractions, and they are used as food in Africa, Asia, the Pacific and the Caribbean. Due to their physiology, bats are one type of animal that acts as a natural reservoir of many pathogens, such as rabies; and since they are highly mobile, social, and long-lived, they can readily spread disease among themselves. If humans interact with bats, these traits become potentially dangerous to humans.

Depending on the culture, bats may be symbolically associated with positive traits, such as protection from certain diseases or risks, rebirth, or long life, but in the West, bats are popularly associated with darkness, malevolence, witchcraft, vampires, and death.

Remove ads

Etymology

A dialectal English name for bats is flittermouse, which matches their name in other Germanic languages (for example German Fledermaus and Swedish fladdermus), related to the fluttering of wings. Middle English had bakke, most likely cognate with Old Swedish natbakka ('night-bat'), which may have undergone a shift from -k- to -t- (to Modern English bat) influenced by Latin blatta, 'moth, nocturnal insect'. The word bat was probably first used in the early 1570s.[2][3] The order name Chiroptera derives from Ancient Greek χείρ (kheír), meaning "hand",[4] and πτερόν (pterón), meaning "wing".[5][6]

Remove ads

Phylogeny and taxonomy

Summarize

Perspective

Evolution

The delicate skeletons of bats do not fossilise well; it is estimated that only 12% of bat genera that lived have been found in the fossil record.[7] The oldest known bat fossils include Archaeonycteris praecursor and Altaynycteris aurora (55–56 million years ago), both known only from isolated teeth.[8][9] The oldest complete bat skeleton is Icaronycteris gunnelli and Onychonycteris finneyi (52 million years ago), known from two skeletons discovered in Wyoming.[1][10] The extinct bats Palaeochiropteryx tupaiodon and Hassianycteris kumari, both of which lived 48 million years ago, are the first fossil mammals whose colouration has been discovered: both were reddish-brown.[11]

Bats were formerly grouped in the superorder Archonta, along with the treeshrews (Scandentia), colugos (Dermoptera), and primates.[12] Modern genetic evidence now places bats in the superorder Laurasiatheria, with its sister taxon as Ferungulata, which includes carnivorans, pangolins, odd-toed ungulates, and even-toed ungulates.[13][14][15][16][17] One study places Chiroptera as a sister taxon to odd-toed ungulates (Perissodactyla).[18]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogenetic tree showing Chiroptera within Laurasiatheria, with Fereuungulata as its sister taxon according to a 2013 study[17] |

The flying primate hypothesis proposed that when adaptations to flight are removed, megabats are allied to primates and colugos by anatomical features not shared with microbats and thus flight evolved twice in mammals.[19] Genetic studies have strongly supported the common ancestry of all bats and the single origin of mammal flight.[1][19]

Coevolutionary evidence

An independent molecular analysis trying to establish the dates when bat ectoparasites (bedbugs) evolved came to the conclusion that bedbugs similar to those known today (all major extant lineages, all of which feed primarily on bats) had already diversified and become established over 100 million years ago, suggesting that they initially all evolved on non-bat hosts and "bats were colonized several times independently, unless the evolutionary origin of bats has been grossly underestimated."[20] No analysis has provided estimates for the age of the flea lineages associated with bats. The oldest known members of a different lineage of bat ectoparasites (bat flies), however, are from roughly 20 million years ago, well after the origin of bats.[21] The bat-ectoparasitic earwig family Arixeniidae has no fossil record, but is not believed to originate more than 23 million years ago.[22]

Inner systematics

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internal relationships of the Chiroptera, divided into the traditional megabat and microbat clades, according to a 2011 study[23] |

A 2011 study supported separating megabats and microbats.[23] However, other and more recent evidence indicates that megabats belong within the microbats.[17] Two new suborders have been proposed; Yinpterochiroptera includes the Pteropodidae, or megabat family, as well as the families Rhinolophidae, Hipposideridae, Craseonycteridae, Megadermatidae, and Rhinopomatidae. Yangochiroptera includes the other families of bats (all of which use laryngeal echolocation), a conclusion supported by a 2005 DNA study.[24] A 2013 phylogenomic study supported the two new proposed suborders.[17]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internal relationships of the Chiroptera, with the megabats subsumed within Yinpterochiroptera, according to a 2013 study[17] |

The 2003 discovery of an early fossil bat from the 52-million-year-old Green River Formation, Onychonycteris finneyi, indicates that flight evolved before echolocative abilities. Unlike mordern bats, Onychonycteris had claws on all five of its fingers. It also had longer hind legs and shorter forearms, possible adaptations for climbing. This palm-sized bat had short, broad wings, suggesting that it could not fly as fast or as far as later bat species. Instead of flapping its wings continuously while flying, Onychonycteris probably switched between flaps and glides in the air.[1] Hence flight in bats likely developed from gliding.[25] and in arboreal locomotors, rather than terrestrial runners. This model of flight development, commonly known as the "trees-down" theory, holds that bats first flew by taking advantage of height and gravity to drop down on to prey, rather than running fast enough for a ground-level take off.[26][27]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Familial relationships of bats according to a 2023 study using mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from 151 species. Two different analysis methods were used which resulted in almost identical trees, except for the position of Emballonuroidea and the relationships between Rhinolophidae, Hipposideridae, and Rhinonycteridae, which are represented as polytomies.[28] |

The molecular phylogeny was controversial, as it pointed to microbats not having a unique common ancestry, which implied that some seemingly unlikely transformations occurred. The first is that laryngeal echolocation evolved twice in bats, once in Yangochiroptera and once in the rhinolophoids.[29] The second is that laryngeal echolocation had a single origin in Chiroptera, was lost in the family Pteropodidae (all megabats), and later evolved as a system of tongue-clicking in the genus Rousettus.[30] Analyses of the sequence of the vocalisation gene FoxP2 were inconclusive on whether laryngeal echolocation was lost in the pteropodids or gained in the echolocating lineages.[31] Echolocation probably first derived in bats from communicative calls. The Eocene bats Icaronycteris (52 million years ago) and Palaeochiropteryx had cranial adaptations suggesting an ability to produce ultrasound. This may have been used at first mainly to forage on the ground for insects and map out their surroundings in their gliding phase, or for communicative purposes. After the adaptation of flight was established, it may have been refined to target flying prey.[25] A 2008 analysis of the hearing gene Prestin seems to favour the idea that echolocation developed independently at least twice, rather than being lost secondarily in the pteropodids,[32] but ontogenic analysis of the cochlea supports that laryngeal echolocation evolved only once.[33]

Classification

Bats are placental mammals. After rodents, they are the largest order, making up about 20% of known mammal species.[34][35] In 1758, Carl Linnaeus classified the seven bat species he knew of in the genus Vespertilio in the order Primates. Around twenty years later, the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach gave them their own order, Chiroptera.[36] Since then, the number of described species has risen to over 1,500,[37] traditionally classified as two suborders: Megachiroptera (megabats), and Microchiroptera (microbats/echolocating bats).[38] Not all megabats are larger than microbats.[39] Several characteristics distinguish the two groups. Microbats use echolocation for navigation and finding prey, but megabats apart from those in the genus Rousettus do not.[40] Accordingly, megabats have a well-developed eyesight.[38] Megabats have a claw on the second finger of the forelimb, external ears close to form a ring and lack of a tail.[41][38] They only feed on plant material like fruit and nectar.[38]

Below is a table chart following the bat classification of families recognised by various authors of the ninth volume of Handbook of the Mammals of the World published in 2019:[42]

Remove ads

Anatomy and physiology

Summarize

Perspective

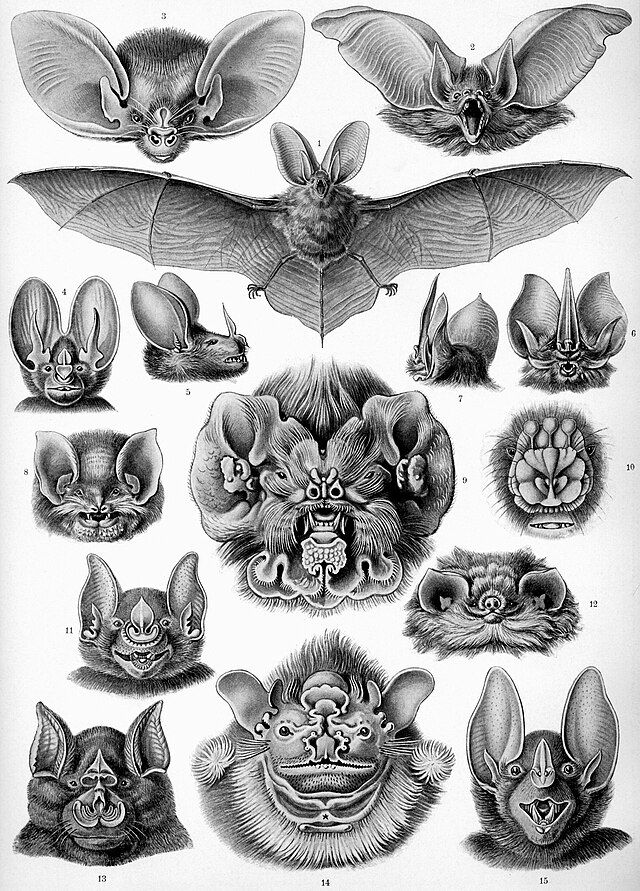

Skull and dentition

The head and teeth shape of bats can vary by species. In general, megabats have a fox-like appearance with long snouts and ears, hence their nickname of "flying foxes".[38] Among microbats, longer snouts are associated with nectar-feeding,[43] while vampire bats have reduced snouts.[44] The number of teeth in bats can vary between 38 teeth in small, insect-eating species, and as low as 20 in vampire bats. A diet of hard-shelled insects requires fewer but larger teeth along with longer canines and more robust lower jaws. In nectar-feeding bats, the canines are long while the cheek-teeth are reduced. In fruit-eating micro-bats, the cusps of the cheek teeth are adapted for crushing.[43] The upper incisors of vampire bats lack enamel, which keeps them razor-sharp.[44] The bite force of small bats is generated through mechanical advantage, allowing them to bite through the hardened armour of insects or the skin of fruit.[45]

Wings, skin and flight

Bats are the only mammals capable of sustained flight, as opposed to the gliding of flying squirrels, colugos and sugar gliders.[46][47] The fastest bat, the Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), can achieve a ground speed of 160 km/h (100 mph).[48]

The flexible finger bones of bats have a flattened cross-section and become less mineralised towards the tips.[49][50] The elongation of bat digits, a key feature required for wing development, is due to the upregulation of bone morphogenetic proteins (Bmps). During embryonic development, the gene controlling Bmp signalling, Bmp2, is subjected to increased expression in bat forelimbs – resulting in the extension of the manual digits. This crucial genetic alteration helps create the specialised limbs required for powered flight. The relative proportion of extant bat forelimb digits compared with those of Eocene fossil bats have no significant differences, suggesting that bat wing morphology has been conserved for over fifty million years.[51] During flight, the bones undergo bending and shearing stress; the former being less than in terrestrial mammals, and the latter being greater. The wing bones of bats are less resistant to breaking than those of birds.[52]

As in other mammals, and unlike in birds, the radius is the main component of the forearm. Bats have five elongated digits, which all radiate around the wrist. The thumb points forward and supports the leading edge of the wing, and the other digits support the tension held in the wing membrane. The second and third digits go along the wing tip, allowing the wing to be pulled forward against aerodynamic drag, without having to be thick as in pterosaur wings. The fourth and fifth digits go from the wrist to the trailing edge, and repel the bending force caused by air pushing up against the stiff membrane. The knees point upwards and outwards during flight due to the attachment of the femurs, while the ankle joint can bend the trailing edge downwards.[53]

Due to their flexible joints, bats are more maneuverable and more dexterous than gliding mammals.[54] and their thin, articulated wings allow them to maneuver more accurately than birds, and fly with more lift and less drag.[55] By folding the wings in toward their bodies on the upstroke, they save 35 percent energy during flight.[50] Flight muscles used for the upstroke are located on the back, while those for the downstroke are at the chest. This is in contrast to birds where both muscle types are at the chest.[56] Nectar- and pollen-eating bats can hover in a similar way to hummingbirds. The sharp leading edges of the wings can create vortices, which provide lift. The vortex may be stabilised by the animal changing its wing curvature.[57]

The patagium is the wing membrane; which reaches from the arm and finger bones, to the side of the body and the hindlimbs.[58] The extent to which the tail of a bat is attached to a patagium can vary by species, with some having completely free tails or even no tails.[43] For bat embryos, only the hindfeet experience apoptosis (programmed cell death), while the forefeet retain webbing between the fingers that become the wing membranes.[59] These structures include connective tissue, elastic fibres, nerves, muscles, and blood vessels. The muscles keep the membrane taut as the animal flies.[58]

While the skin on the body of the bat is covered in hair and sweat glands with an epidermis, a dermis, and a fatty subcutaneous layer, the patagium is an extremely thin double layer of epidermis separated by a connective tissue centre, rich with collagen and elastic fibers.[60][61] The surface of the wings is equipped with touch-sensitive receptors on small bumps called Merkel cells. Each bump has a tiny hair in the centre, allowing the bat to detect and adapt to changing airflow; the primary use is to judge the most efficient speed at which to fly, and possibly also to avoid stalls.[62] Insectivorous bats may also use tactile hairs when maneuvering to capture flying insects.[54] While delicate, the membranes can heal quickly and regrow when torn.[63][64]

Photoluminescence has been reported in at least six North American species based on 60 museum specimens. The wings, uropatagium (around the tail), and hind limbs of these bats glowed green when exposed to UV light.[65] The explanation for this is uncertain, and some have suggested the phenomenon is an artifact of the techniques used to dry specimens for museum storage.[66][67]

Roosting and gaits

When not flying, bats hang upside down from their feet, a posture known as roosting. Most megabats roost with the head tucked towards the belly, whereas most microbats roost with the neck curled towards the back. This difference is due to structure of the cervical or neck vertebrae in the two groups, which are clearly distinct.[68] Tendons allow bats to hang from a roost with no effort, which is needed to release.[69]

Bats are more awkward when crawling on the ground, though a few species such as the New Zealand lesser short-tailed bat (Mystacina tuberculata) and the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) are quite agile. These species move their limbs one after the other, but vampire bats accelerate by bounding, the folded up wings being used to propel them forward. Vampire bats likely evolved these gaits to stalk their hosts while short-tailed bats took to the ground due to a lack of competition from other mammals. Terrestrial locomotion does not appear to effect their ability to fly.[70]

Internal systems

Bats have an efficient circulatory system. They seem to make use of particularly strong venomotion, a rhythmic contraction of venous wall muscles. In most mammals, the walls of the veins provide mainly passive resistance, maintaining their shape as deoxygenated blood flows through them, but in bats they appear to actively support blood flow back to the heart with this pumping action.[71][72] Because of their small, lightweight bodies, bats are not at risk of blood rushing to their heads when roosting.[73] Compared to a terrestrial mammal of similar size, the bat's heart can be up to three times larger, and pump more blood, while blood oxygen levels are twice as much.[74] An active microbat can reach a heart rate of 1000 beats per minute.[75]

Bats possess a highly adapted respiratory system to cope with the demands of powered flight. They have relatively large lungs and many species have proportionally larger alveolar surface areas and pulmonary capillary blood volumes than other mammals.[76] During flight the respiratory cycle has a one-to-one relationship with the wing-beat cycle.[77] Their mammalian lungs prevent them from flying at high altitudes.[53] Bats can also meet oxygen demands by exchanging gas through the patagium of the wing. When the bat has its wings spread it allows for an increase in surface area to volume ratio, 85% of the surface area being the wing.[78] The subcutaneous vessels in the membrane lie near the surface and allow for the diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide.[79]

The digestive system of bats varies depending on the species of bat and its diet. Digestion is relatively quick to meet the energy demands of flight. Insectivorous bats may have certain digestive enzymes to better process insects, such as chitinase to break down their chitin exoskeleton.[80] Vampire bats, probably due to their diet of blood, are unique among vertebrates in that they do not have the enzyme maltase, which breaks down malt sugar, in their intestinal tract. Nectivorous and frugivorous bats have more maltase and sucrase enzymes than insectivores, to cope with the higher sugar contents of their diet.[81]

The adaptations of the kidneys of bats vary with their diets. Carnivorous and vampire bats consume large amounts of protein and can output concentrated urine; their kidneys have a thin cortex and long renal papillae. Frugivorous bats lack that ability and have kidneys adapted for electrolyte-retention due to their low-electrolyte diet; their kidneys accordingly have a thick cortex and very short conical papillae.[81] Flying gives bats relatively high metabolism, which increases respiratory water loss. Lipids known as cerebrosides retain water in cold temperatures but allow for evaporation though the skin in hot temperatures to cool them.[82] Water helps maintain the ionic balance in their blood, thermoregulation system and urinary and waste system. They are also susceptible to blood urea poisoning if they do not receive enough fluid.[83]

The structure of the uterine system in female bats can vary by species, with some having two uterine horns while others have a single mainline chamber.[84]

Senses

Echolocation and hearing

Microbats and a few megabats emit ultrasonic sounds to produce echoes. Sound intensity of these echos are dependent on subglottic pressure. The bats' cricothyroid muscle, located inside the larynx, controls the orientation pulse frequency, which is an important function.[85] By comparing the outgoing pulse with the returning echoes, bats can learn about their environment and detect prey in darkness.[86] Some bat calls can reach over 140 decibels.[87] Microbats use their larynx to emit echolocation signals through the mouth or the nose.[88] Bat call frequencies range from as low as 11 kHz to as high as 212 kHz.[89] The noses of various groups of bats have fleshy extensions, known as nose-leaves, which play a role in sound transmission.[90]

In low-duty cycle echolocation, bats can separate their calls and returning echoes by time. They have to time their short calls to finish before echoes return.[89] In high-duty cycle echolocation, bats emit a continuous call and separate pulse and echo in frequency using the Doppler effect of their motion in flight. The shift of the returning echoes yields information relating to the motion and location of the bat's prey. These bats must deal with changes in the Doppler shift due to changes in their flight speed. They have adapted to change their pulse emission frequency in relation to their flight speed so echoes still return in the optimal hearing range.[89][91]

In addition to echolocating prey, bat ears are sensitive to sounds made by their prey, such as the fluttering of moth wings. The complex geometry of ridges on the inner surface of bat ears helps to sharply focus echolocation signals, and to passively listen for any other sound produced by the prey. These ridges can be regarded as the acoustic equivalent of a Fresnel lens.[92] Bats can estimate the elevation of their target using the interference patterns from the echoes reflecting from the tragus, a flap of skin in the external ear.[93]

By repeated scanning, bats can mentally construct an accurate image of the environment in which they are moving and of their prey.[94] Many species of moth have exploited this, such as many tiger moths, which produce aposematic ultrasound signals to warn bats that they are chemically protected and therefore distasteful.[95] Some tiger moths can produce signals to jam bat echolocation.[96] In some moth species, the tympanum hearing organ causes the insect to move in random evasive manoeuvres when detecting a bat call.[97]

Vision

Microbats tend to have small eyes, but are still sensitive to light and no species is truly blind.[98] Most microbats have mesopic vision, meaning that they can detect light only in low levels, whereas other mammals have photopic vision, which allows colour vision. Microbats may use their vision for orientation and while travelling between their roosting grounds and feeding grounds, as echolocation is effective only over short distances. Megabat species generally have good eyesight and may have some colour vision to help them distinguish ripe fruits. Some species can detect ultraviolet (UV). As the bodies of some microbats have distinct coloration, they may be able to discriminate colours.[46][99][100][101]

Smell

Among bat species, megabats tend to have a more developed sense of smell, being particularly sensitive to esters which are found in ripe fruits.[102] Similarly, smell is also important for vampire bats, which sense a potential host by their fur or faeces.[103] Insectivorous bats have less use for smell during foraging as they rely on echolocation to search for prey.[102]

Magnetoreception and infrared sensing

Like birds, microbats' sensitivity to the Earth's magnetic field gives them great magnetoreception. Microbats use a polarity-based compass, which means they can distinguish north from south, unlike birds, which use the strength of the magnetic field to differentiate latitudes, which may be used in long-distance travel. The mechanism possibly involves magnetite particles.[104][105] Vampire bats are the only mammals that use infrared sensing; heat sensors around the nose allow them to detect blood vessels near the surface of the skin of their target.[106]

Thermoregulation

Tropical bats tend to be homeothermic (having a stable body temperature), while temperate and subtropical species which enter hibernation or torpor are more heterothermic (where body temperature can vary).[107][108] Compared to other mammals, bats have a high thermal conductivity. They lose heat via the wings when they are spread, so resting bats wrap their wings around themselves to keep warm. Smaller bats generally have a higher metabolic rate than larger bats, and so need to consume more food in order to maintain homeothermy.[109]

Bats may avoid flying during the day to prevent overheating in the sun, since they would absorb sun radiation via their dark wing-membranes. Bats may not be able to release heat if the ambient temperature is too high;[110] they use saliva to cool themselves in extreme conditions.[111] Among megabats, the flying fox Pteropus hypomelanus uses saliva and wing-fanning to cool itself while roosting during the hottest part of the day.[112] Among microbats, the Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis), the Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), and the pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus) cope with temperatures up to 45 °C (113 °F) by panting, salivating, and licking their fur to promote evaporative cooling; this is sufficient to releasing twice their metabolic heat production.[113]

During torpor, bats drop their body temperature to 6–30 °C (43–86 °F), while their energy usage diminishes by 50 to 99%.[114] Tropical bats may use it to reduce the chance of being caught by a predator during foraging.[115] Megabats were generally believed to be homeothermic, but three species of small megabats, with a mass of about 50 grams (1+3⁄4 ounces), have been known to use torpor: the common blossom bat (Syconycteris australis), the long-tongued nectar bat (Macroglossus minimus), and the eastern tube-nosed bat (Nyctimene robinsoni). Torpid states last longer in the summer for megabats than in the winter.[116]

During hibernation, bats enter a torpid state and decrease their body temperature for 99.6% of their hibernation period; even during periods of arousal, when their body temperature returns to normal, they sometimes enter a shallow torpid state, known as "heterothermic arousal".[117] Some bats become dormant during higher temperatures to keep cool in the summer months (aestivation).[118]

Heterothermic bats during long migrations may fly at night and go into a torpid state roosting in the daytime. Unlike migratory birds, which fly during the day and feed during the night, nocturnal bats have a conflict between travelling and eating. The energy saved reduces their food requirements, and also decreases the duration of migration, which may prevent them from spending too much time in unfamiliar places, and decrease predation. In some species, pregnant individuals use a more moderate state of torpor to maintain fetal development, while still saving energy.[119][120]

Size

The smallest bat, and one of the smallest mammals, is Kitti's hog-nosed bat (Craseonycteris thonglongyai), which is 29–33 mm (1+1⁄8–1+1⁄4 in) long with a 150-millimetre (6 in) forearm and weighs 2 oz (56+11⁄16 g).[121] The largest species is the Giant golden-crowned flying fox, (Acerodon jubatus), which can weigh 1.5 kg (3+1⁄4 lb) with a wingspan of 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in).[122] Larger bats tend to use lower frequencies and smaller bats higher for echolocation; high-frequency echolocation is better at detecting smaller prey. Small prey may be absent in the diets of large bats as they are unable to detect them.[123]

Remove ads

Ecology

Summarize

Perspective

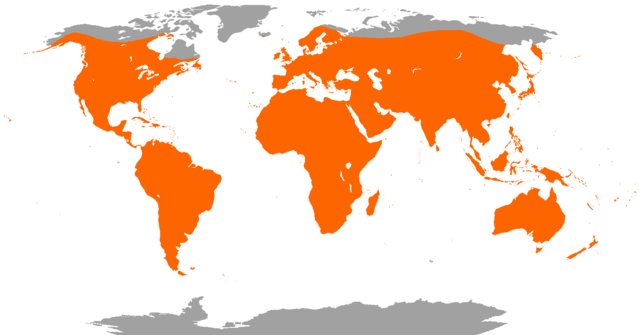

Flight has enabled bats to become one of the most widespread groups of mammals,[124] being found nearly everywhere apart from polar regions, some remote islands and the very top of mountains.[43][125] Species diversity is greater in tropical areas than temperate ones.[126] Bats are about 66% of all mammalian individuals, despite being just 10% of the total biomass of wild terrestrial mammals.[127] Different species select different habitats during different seasons, including ocean coasts, mountains, rainforests and deserts, but they require suitable roosts. Bat roosts can be found in hollows, crevices, foliage, and even human-made structures, and include "tents" the bats construct with leaves;[125] Megabats generally roost in trees.[128] Bats are usually nocturnal,[43] but are known to exhibit diurnal behaviour in temperate regions during summer to make up for insufficient nighttime feeding,[129][130] and where there is little predatory threat from birds.[131][132]

In temperate areas, some bats migrate to winter hibernation dens, usually caves and mines, where they pass into torpor during the cold weather, never waking and relying on their stored fat. Similarly tropical bats go through aestivation during periods of prolonged heat and dryness.[133] Bats rarely fly in rain, possibly because being wet costs them more energy and raindrops interfere with their echolocation.[134] They do appear to surf storm fronts when travelling to give birth in warmer temperatures.[135]

Food and feeding

Different bat species have different diets, including insects, nectar, pollen, fruit and even vertebrates.[136] Megabats are mostly fruit, nectar and pollen eaters.[137][43] Due to their small size, high metabolism and rapid burning of energy through flight, bats must consume large amounts of food for their size. Insectivorous bats may eat over 120 percent of their body weight per day, while frugivorous bats may eat over twice their weight.[138] They can travel significant distances each night, exceptionally as much as 38.5 km (24 mi) in the spotted bat (Euderma maculatum), in search of food.[139] Bats may acquire water from the food they eat or drink from sources like lakes and streams, flying over the surface and dipping their tongues into the water.[140]

Bats as a group appear to be losing vitamin C synthesis.[141] Such a loss was recorded in 34 bat species from six major families, both insect- and fruit-eating, with the cause being a single mutation inherited from a common ancestor.[142][a] Vitamin C synthesis has been recorded in at least two species of bat, Leschenault's rousette (Rousettus leschenaultii) and the great roundleaf bat (Hipposideros armiger).[143]

Insects and invertebrates

Most bats, especially in temperate areas, prey on insects. The diet of an insectivorous bat may span many species,[144] including flies, mosquitos, beetles, moths, grasshoppers, crickets, termites, bees, wasps, mayflies and caddisflies.[43][145][146] They will also eat other arthropods such as spiders, scorpions, centipedes, lobsters and shrimp.[147] Large numbers of Mexican free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) fly hundreds of metres above the ground in central Texas to feed on migrating moths.[148] Species that hunt insects in flight, like the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) and the eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis) may catch an insect in mid-air directly with the mouth, or use their tail membranes or wings.[149] The slow-moving brown long-eared bat (Plecotus auritus) plucks insects from vegetation while many horseshoe bat species wait for them from their perches.[43] Some bats may take the insect to its roost and eat it there.[150] Arthropod-eating bats living at high latitudes have to consume prey with higher energetic value than tropical bats.[151]

Plant material

Consumption of fruit, nectar, pollen and other plant material occurs in megabats and New World leaf-nosed bats. Bats prefer ripe fruit, and typically pull it from a tree and travel somewhere else to feed, possibly to avoid predators, though larger megabats may eat on site at the fruiting tree.[152] The Jamaican fruit bat (Artibeus jamaicensis) has been recorded carrying fruit weighing as much as 50 g (1.8 oz).[153] Many species of plants depend on bats for seed dispersal.[154][155][156] Fruit-eating bats sometimes chew leaves to suck up the moisture, and then spit them out. Bats apparently cannot digest cellulose.[157]

Nectar-eating bats have acquired specialised adaptations. These bats possess long muzzles and long, extensible tongues covered in fine bristles that aid them in feeding on particular flowers and plants.[156][158] The tube-lipped nectar bat (Anoura fistulata) has a proportionally longer tongue than any mammal and the only species capable of reaching deep into the flowers of Centropogon nigri. When the tongue retracts, it is pulled inside the rib cage.[159] Because of these features, nectar-feeding bats cannot easily turn to other food sources in times of scarcity, making them more at risk of extinction than other species.[160][161] Nectar feeding also aids a variety of plants, since these bats serve as pollinators, as pollen attaches to their fur while they feed. Around 500 species of flowering plant rely on bat pollination and thus tend to open their flowers at night.[156] Many rainforest and Mediterranean plants depend on bat pollination.[162][154]

Vertebrates

Some bats prey on other vertebrates, such as fish, frogs, lizards, birds and mammals.[43][163] The fringe-lipped bat (Trachops cirrhosus), for example, is skilled at catching frogs. locating them by tracking their mating calls.[164] The greater noctule bat (Nyctalus lasiopterus) will hunt and catch birds in flight.[165][166] Some species, like the greater bulldog bat (Noctilio leporinus) hunt fish, flying over the water and grabbing them with their clawed feet. They use echolocation and may be alerted by ripples on the surface or a jumping fish.[167] Some species species feed on other bats, including the spectral bat (Vampyrum spectrum), and the ghost bat (Macroderma gigas).[168]

Blood

The three species of vampire bat strictly feed on animal blood (hematophagy); the common vampire bat feeding on mammals while the hairy-legged (Diphylla ecaudata) and white-winged vampire bats (Diaemus youngi) feed on birds.[169] Vampire bats target sleeping prey and can sense deep breathing.[170] They cut through and peel the animal's skin with their teeth, and lap up the blood with their tongues, which have grooves on the underside adapted to this purpose. Certain substances in the salvia keep the blood flowing.[171]

Predators, parasites, and diseases

Bats are subject to predation from birds of prey, such as owls, hawks, and falcons. J. Rydell and J. R. Speakman argue that bats evolved nocturnality during the early Eocene period to avoid predators.[172] Other zoologists find the evidence to be unclear and contradictory.[173] Twenty species of tropical New World snakes are known to eat bats; they may wait for them at the entrances of their refuges or attack them inside.[174] As are most mammals, bats are hosts to a number of internal and external parasites.[175] Among ectoparasites, bats carry fleas and mites, as well as specific parasites such as bat bugs and bat flies (Nycteribiidae and Streblidae).[176][177] Bats generally do not host lice, possibly due to high competition from other parasites including the more specialised ones.[177] Internal parasites of bats include tapeworms, roundworms and flukes.[175]

White nose syndrome is a condition associated with the deaths of millions of bats in North America. The disease is named after a white fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, found growing on the muzzles, ears, and wings of affected bats. The fungus is mostly spread from bat to bat, and cause weight loss, dehydration and electrolyte imbalances.[178][179] The fungus was first discovered in central New York State in 2006 and spread to 30 US states and five Canadian provinces, mortality rates as high as 99% have occurred for affected bat wintering caves.[180][178] To treat the disease, scientists have used probiotic dermal bacteria and anti-fungal vaccines which can improve survival by as much as 50%.[181]

Bats are natural reservoirs for a large number of zoonotic pathogens,[182] including rabies, endemic in many bat populations,[183][184][185] histoplasmosis both directly and in guano,[186] Nipah and Hendra viruses,[187][188] and possibly the ebola virus.[189][190] Their high mobility, broad distribution, long life spans, substantial sympatry (range overlap) of species, and social behaviour make bats favourable hosts and vectors of disease.[191] Reviews have found different answers as to whether bats have more zoonotic viruses (transferable to humans) than other mammal groups. One 2015 review found that among mammals, bats, rodents, and primates harboured the most zoonotic viruses by a significant margin, though bats had about as many zoonotic viruses as rodents and primates.[192] Another 2020 review of mammals and birds found that the taxon of the reservoir was not a factor in whether a virus was zoonotic. Instead, more diverse groups had greater viral diversity.[193]

Bats seem to be highly resistant to many of the pathogens they carry, suggesting a degree of adaptation to their immune systems.[191][194][195] Their interactions with livestock and pets, including predation by vampire bats, compound the risk of zoonotic transmission.[184] Bats have been connected to the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in China, since they serve as natural hosts for coronaviruses, several from a cave in Yunnan, one of which developed into the SARS virus.[186][196][197] However, there is no evidence that bats "cause or spread" COVID-19.[198]

Remove ads

Behaviour and life history

Summarize

Perspective

Social structure

Bats may roost solitarily or in colonies;[200] Mexican free-tailed bats roost in the millions while the hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus) is mostly solitary, aside from mothers with young.[201] Living in large colonies lessens the risk to an individual of predation.[43] Temperate bat species may swarm at hibernation sites as autumn approaches. This may serve to guide young to these sites, signal reproduction in adults and allow adults to breed with those from other groups.[202]

Several species have a fission-fusion social structure, where large numbers of bats congregate in one roosting area, along with breaking up and mixing of subgroups. Within these societies, long-term relationships form despite the fluidity of grouping.[203] Some of these relationships consist of matrilineally related females and their dependent offspring.[204] Food sharing and mutual grooming is known to occur in species like the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus).[205][206] Homosexual fellatio has been observed in the Bonin flying fox (Pteropus pselaphon) and the Indian flying fox (Pteropus medius), though the function and purpose of this behaviour is not clear.[207][208]

Communication

Bats produce calls to attract mates, find roost partners and defend resources. These calls are typically low-frequency and wide-travelling.[43] Species like Daubenton's bat (Myotis daubentonii) are capable of lowering their vocal range in a matter similar to a death growl, which they use in conflict with other individuals.[209] Mexican free-tailed bats are one of the few species to "sing" like birds. Males sing to attract females and their songs consist of chirps, trills and buzzes, the first of which has distinct "A" and "B" syllables. Bat songs are highly stereotypical but differ in syllable number, phrase order, and phrase repetitions between individuals.[210] Among greater spear-nosed bats (Phyllostomus hastatus), females produce loud, broadband calls among their roost mates to form group cohesion. Roosting groups have their own distinct calls and these and may arise from vocal learning.[211]

In a study on captive Egyptian fruit bats, 70% of the directed calls could be identified by the researchers as to which individual bat made it, and 60% could occurred in four contexts: fights over food, quarreling for a sleeping position, female aggression toward amorous males and arguing between perched neighbours. The animals made slightly different sounds when communicating with different individual bats, especially those of the opposite sex.[212] In the highly sexually dimorphic hammer-headed bat (Hypsignathus monstrosus), males display to females with a "deep, resonating, monotonous call". Bats in flight make vocal signals for traffic control. Greater bulldog bats honk when on a collision course with each other.[213]

Bats also communicate by other means. Male little yellow-shouldered bats (Sturnira lilium) use a spicy odour secreted from their shoulder glands during the breeding season, retained and spread by specialised hairs. These hairs exist in other species, which are noticeable as collars around the necks in some Old World megabat males. Male greater sac-winged bats (Saccopteryx bilineata) have sacs in their wings in which they mix body secretions like saliva and urine to create a perfume that they sprinkle on roost sites, a behaviour known as "salting". The bats may sing while salting.[213]

Reproduction and life cycle

Most bat species are polygynous, where males mate with multiple females. Male pipistrelle, noctule and vampire bats may claim and defend resources that attract females, such as roost sites, and mate with those females. Males unable to claim a site are forced to live on the periphery where they have less reproductive success.[214][43] Promiscuity, where both sexes mate with multiple partners, exists in species like the Mexican free-tailed bat and the little brown bat.[215][216] There appears to be bias towards certain males among females in these bats.[43] In a few species, such as the yellow-winged bat (Lavia frons) and spectral bat, adult males and females form monogamous pairs.[43][217] Lek mating, where males aggregate and compete for female choice through display, is rare in bats[218] but occurs in the hammerheaded bat.[219]

Temperate living bats typically mate during later summer and autumn,[220] while tropical bats may mate multiple times a year. In hibernating species, males will copulate with females in torpor.[43] Female bats use a variety of strategies to control the timing of pregnancy and the birth of young, to make delivery coincide with maximum food ability and other ecological factors. Females of some species have delayed fertilisation, in which sperm is stored in the reproductive tract for several months after mating. Mating occurs in late summer to early autumn but fertilisation is delayed until the following late winter to early spring. Other species exhibit delayed implantation, in which the egg is fertilised after mating, but does not experience all its cell divisions until external conditions become favourable.[221] In another strategy, fertilisation and implantation both occur, but development of the foetus is delayed until good conditions prevail. During the delayed development the mother keeps the fertilised egg alive with nutrients. This process can go on for a long period, because of the advanced gas exchange system.[222]

Gestation in bats ranges from around 40 days to eight months correlating with the size of species.[223] In most bat species, females carry and give birth to a single pup per litter. A newborn bat pup can be up to 40 percent of the mother's weight,[43] and the pelvic girdle of the female can expand during birth as the two halves are connected by a flexible ligament.[224] Females typically give birth up-right or horizontally using gravity to make the process easier. The young emerges rear-first, possibly to prevent the wings from becoming tangled, and the female holds it in her wing and tail membranes. In many species, females give birth and raise their young in maternity colonies and may assist each other in birthing.[225][226][227]

Most of the care for a young bat comes from the mother, though in monogamous species, the father plays a role. Allo-suckling, where a female suckles another mother's young, occurs in several species. This may serve to increase colony size in species where females breed in their birth colonies.[43] Young bats can fly after they develop their adult body dimensions and forelimb length. For the little brown bat, this occurs when they are eighteen days old. Weaning of young for most species takes place in under 80 days. The common vampire bat nurses its offspring beyond that and young vampire bats achieve independence later in life than other species. This is probably due to the species' blood-based diet, as the female may not be able feed on nightly basis.[228]

Life expectancy

The maximum lifespan of bats is three-and-a-half times that of other mammals of similar size; a Siberian bat (Myotis sibiricus) was recaptured in the wild after 41 years, making it the oldest known bat.[229] One hypothesis consistent with the rate-of-living theory links this to the fact that they slow down their metabolic rate while hibernating; bats that hibernate, on average, have a longer lifespan than bats that do not.[230][231] Another hypothesis is lower mortality is linked to flying, which would also be true for birds and gliding mammals. In addition, females bats that give birth to multiple pups annually generally have a reduced lifespans compared to those that have one pup. Also, cave-roosting species may have a longer lifespan than non-roosting species due to less predation in caves.[231][229]

Remove ads

Conservation

Summarize

Perspective

Conservation statuses of bats as of 2020 according to the IUCN (1,314 species in total)[232]

- Critically endangered (1.60%)

- Endangered (6.30%)

- Vulnerable (8.30%)

- Near-threatened (6.70%)

- Least concern (58.0%)

- Data deficient (18.4%)

- Extinct (0.70%)

Groups such as the Bat Conservation International[233] aim to increase awareness of bats' ecological roles and the environmental threats they face. This group called for Bat Appreciation Week from October 24–31 every year to promote awareness on the ecological importance of bats.[234] In the United Kingdom, all bats are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Acts, and disturbing a bat or its roost can be punished with a heavy fine.[235] In Sarawak, Malaysia, "all bats"[236] are protected under the Wildlife Protection Ordinance 1998,[236] but species such as the hairless bat (Cheiromeles torquatus) are still eaten by the local communities.[237] Humans have caused the extinction of several species of bat in modern history, the most recent being the Christmas Island pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi), which was declared extinct in 2009.[238]

Many people put up bat houses to attract bats.[239] The 1991 University of Florida bat house is the largest occupied artificial roost in the world, with around 450,000–500,000 residents.[240] In Britain, thickwalled and partly underground World War II pillboxes have been converted to make roosts for bats,[241][242] and purpose-built 'bat bridges' are occasionally built to mitigate damage to habitat from road or other developments.[243] Cave gates are sometimes installed to limit human entry into caves with sensitive or endangered bat species. The gates are designed not to limit the airflow, and thus to maintain the cave's micro-ecosystem.[244] In the United States, 35 of the 47 bat species roost on human-made structures, while 14 of them use bat houses.[245]

There is evidence that suggests that wind turbines might create sufficient barotrauma (pressure damage) to kill bats.[246] Bats have typical mammalian lungs, which are thought to be more sensitive to sudden air pressure changes than the lungs of birds, making them more liable to fatal rupture.[247][248][249][250][251] Bats may approach turbines to roost on them, increasing the death rate.[247] Ultrasonic signal may help to deter bats from appoarching wind farms, thus reducing deaths.[252] The diagnosis and contribution of barotrauma to bat deaths near wind turbine blades have been disputed by other research comparing dead bats found near wind turbines with bats killed by impact with buildings in areas with no turbines.[253]

The effects of climate change on bats is debated; a 2022 literature review concluded that "Several biological and ecological traits of bats may make them sensitive to climate change, yet there is surprisingly little evidence on how these mammals respond to this anthropogenic environmental pressure."[254] A 2025 study of European species found that bats populations may be sifting their ranges further north. Specifically, range suitability declined markedly in southern Europe while increasing at higher northern latitudes.[255]

Remove ads

Interactions with humans

Summarize

Perspective

Cultural significance

Since bats are mammals, yet can fly, they are considered to be liminal beings in various traditions.[256] In many cultures, including in Europe, bats are associated with darkness, death, witchcraft, and malevolence. Among Native Americans such as the Creek, Cherokee and Apache, the bat is identified as a trickster.[257] An East Nigerian tale tells that the bat developed its nocturnal habits after causing the death of his partner, the bush-rat, and now hides by day to avoid arrest.[258]

More positive depictions of bats exist in some cultures. In China, bats have been associated with happiness, joy and good fortune and symbolise the "Five Blessings": longevity, riches, health, love of virtue and a peaceful passing away.[259] The bat is sacred in Tonga and is often considered the physical manifestation of a separable soul.[260] Mayan people associated bats with the gateway to the realm of the gods, since they live in caves.[261] In the Zapotec civilisation, the bat god presided over corn and fertility.[262]

The Weird Sisters in Shakespeare's Macbeth used the fur of a bat in their brew.[263] In Western culture, the bat is often a symbol of the night and its foreboding nature. The bat is a primary animal associated with fictional characters of the night, both villainous vampires, such as Count Dracula and before him Varney the Vampire,[264] and heroes, such as the DC Comics character Batman.[265]

The bat is sometimes used as a heraldic symbol in many European countries, including France, Belgium, Germany and the UK. They have also been used as symbols in the militaries of the UK, US and Israel.[266] Three US states have an official state bat. Texas and Oklahoma are represented by the Mexican free-tailed bat, while Virginia is represented by the Virginia big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus).[267]

As food

Consumption of bats has occurred globally, particularly in parts of Africa and Asia, and on some islands in the Pacific and Caribbean. The animals may be eaten for their perceived medical benefits or as a delicacy. Western cookbooks have mentioned grilled bats and fruit bat soup.[268]

Economics

Insectivorous bats in particular are especially helpful to farmers, as they control populations of agricultural pests and reduce the need to use pesticides. It has been estimated that bats save the agricultural industry of the United States anywhere from $3.7 billion to $53 billion per year in pesticides and damage to crops. This also prevents the overuse of pesticides, which can pollute the surrounding environment, and may lead to resistance in future generations of insects.[269] Bat dung, a type of guano, is rich in nitrates and is mined from caves for use as fertiliser.[270] Bats have also been tourist attractions, including the Congress Avenue Bridge in Austin, Texas, where over a million Mexican free-tailed bats roost.[271]

Remove ads

See also

- Bat detector – Audio device to detect the presence of bat sound signals

- List of bats of the United States

Explanatory notes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads