Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

1939 New York World's Fair pavilions and attractions

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The 1939 New York World's Fair took place at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York, United States, during 1939 and 1940. The fair included pavilions with exhibits by 62 nations, 34 U.S. states and territories, and over 1,300 corporations. The exhibits were split across seven zones (including an amusement area), and there were also two standalone exhibits. The fair had about 375 buildings when it opened, which were arranged around the fair's theme center, the Trylon and Perisphere. Buildings were color-coded based on the zone where they were located.

The New York World's Fair Corporation (WFC) oversaw the 1939 fair and leased out the land to exhibitors. The WFC built about 100 buildings, which were developed in a classical style, while the remaining buildings were constructed in a variety of styles. Most of the world's major nations had exhibits, and the fairground also hosted exhibits from states, corporations, and various groups. After the fair, some pavilions were preserved or relocated, but the vast majority of structures were demolished.

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Fair

In September 1935, the New York City Board of Estimate voted to allow Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, then an ash dump, to be used as the site of the 1939 New York World's Fair.[1] The New York World's Fair Corporation (WFC) was formed to oversee the exposition in October 1935,[2] and the WFC took over the site in 1936.[3] The WFC announced details of the fair's master plan in October 1936, which called for an exposition themed to "the world of tomorrow".[4] The World's Fair officially opened on April 30, 1939,[5] and its first season ended on October 31, 1939.[6] The fair reopened for a second and final season on May 11, 1940,[7] closing on October 27, 1940.[8] Demolition of the buildings began immediately after the fair ended,[9][10] but seven structures were preserved as part of the park.[11]

There were 1,500 exhibitors on the fair's opening day, representing about 40 industries.[12] In addition, 62 nations and 35 U.S. states or territories (including the U.S. federal government) leased space at the fair.[13] The fairground was divided into seven geographic or thematic zones, five of which had "focal exhibits", as well as two focal exhibits housed in their own buildings.[14] The plan called for numerous wide tree-lined pathways, including a central "Cascade Mall" leading to the Trylon and Perisphere.[15][16] The zones around the Trylon and Perisphere were all color-coded.[17][18] Despite the fair's futuristic theme, the fairground's layout—with streets radiating from the theme center—was heavily inspired by classical architecture.[16] Some streets in the fairground were named after notable Manhattan thoroughfares or American historical figures, while others were named based on their function.[19]

Pavilions

The fair had about 375 buildings, of which 100 were developed by the WFC.[20] Many of the buildings were designed in "symbolically representative and stylistically individualistic" styles.[16] The pavilions relied almost entirely on artificial light,[21][22] and their steel frames were bolted together so they could be easily disassembled after the fair.[17] The smallest standalone exhibition building was the House of Jewels, which covered 9,928 square feet (922.3 m2), while the largest was the General Motors pavilion, which covered 299,439 square feet (27,818.8 m2).[23]

The buildings included design features such as domes, spirals, buttresses, porticos, rotundas, tall pylons, and corkscrew-shaped ramps.[21][24] The buildings developed by the WFC tended to follow specific design guidelines.[20] In particular, these buildings were generally one story high and made of steel, gypsum, and stucco, while the interiors were split into spaces of uniform dimensions.[25] In contrast to the WFC's buildings, which had a classical architectural style, many of the individual exhibitors built more modernistic structures with curving facades.[26] Many of the buildings' facades were decorated with art, commissioned by both the WFC and by individual exhibitors;[27][28][29] the artwork included large murals, sculptures, and reliefs.[30] The structures were painted in about 100 hues, and some of the paint colors were developed specifically for the fair.[29] Ernest Peixotto oversaw the development of the murals and the fair's color-coding system.[31]

Remove ads

Communications and Business Systems Zone

Summarize

Perspective

Fairgoers walking to the north of the Theme Center on the Avenue of Patriots would encounter the Communications and Business Systems exhibits. The focal point of this area was the Communications Building, a large structure designed by Francis Keally and Leonard Dean, with a pair of 160-foot-high (49 m) pylons flanking it[32][33] and a mural by Eugene Savage.[27] Numerous smaller exhibitors had space in the Communications Building.[34] The structure also had a theater, a Stuart Davis mural about technology, and seven illuminated panels about communications technologies.[32] The building was renamed the Maritime, Transport and Communications Building in 1940.[35]

The Communications and Business Systems Zone also contained the following buildings:

Remove ads

Community Interest Zone

Summarize

Perspective

The Community Interest Zone was located just east of the Communications & Business Systems Zone.[47] The region's exhibits showcased several trades or industries that were popular among the public at the time, such as home furnishings, plumbing, contemporary art, cosmetics, gardens, the gas industry, fashion, jewelry, and religion.[48] The focal exhibit was the Home Furnishings Building, designed by Dwight James Baum; there were several displays from major companies, five smaller displays about home furnishings, and a mural by J. Scott Williams.[49] Besides the focal exhibit, the Community Interest Zone included the following buildings:

Remove ads

Government Zone

Summarize

Perspective

The Government Zone was located at the east end of the fair, on the eastern bank of the Flushing River. It contained a centrally located Court of Peace, a Lagoon of Nations, and a smaller Court of States.[74][75] The Hall of Nations consisted of eight buildings,[75] which flanked the Court of Peace.[76] The 60 foreign governments built many pavilions housing a myriad of cultural offerings.[74][77] Nations could build their own pavilions or lease space in the Hall of Nations; some nations chose to do both.[78] Nazi Germany was the only major country that did not have any exhibits at the fair,[79][23] though this was more because of the Germans' lack of money than opposition to the Nazi regime.[80] China initially did not have a pavilion at the fair due to the ongoing Sino-Japanese War,[23] but a Chinese exhibit was added during the 1940 season.[81] The U.S. government also developed a pavilion for smaller South American and European governments that could not afford their own pavilions.[82] The Soviet pavilion, demolished after the 1939 season, was replaced with the American Common in 1940.[83]

Standalone pavilions

The following nations had standalone pavilions.[84]

Hall of Nations

The following nations were located in the Hall of Nations. Some of these nations only had space in the Hall of Nations, while other nations had space both in the Hall of Nations and in a standalone pavilion.[84]

- British Pavilion

- Italian Pavilion

- Jewish Palestine Pavilion

- The Netherlands Garden, located in the Netherlands Pavilion exhibit

- Polish Pavilion

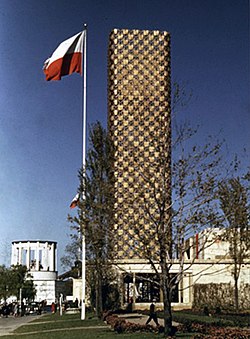

- Swedish Pavilion

- USSR Pavilion at night

States

The fair included pavilions for 33 U.S. states and Puerto Rico.[12] While most of the pavilions surrounded a small, tree-lined lagoon in the Court of States,[169] the pavilions of New York and Florida were outside the Court of States.[170][171] Fourteen states or territories occupied their own buildings, while the rest were built by the WFC.[12] The buildings' designs generally included details that were influenced by the English, French, Georgian, and Spanish architectural styles.[169] Some of the pavilions were replicas of notable buildings or architectural styles in each state; for example, Pennsylvania's pavilion was a replica of Independence Hall, while Texas's pavilion was a copy of the Alamo Mission.[172] The New England states (with the exception of Maine) shared space in an area that was designed to resemble a New England waterfront.[171][172] The Court of States also included exhibits from many of the southeastern states, each of which had individual pavilions.[171][173]

Remove ads

Food Zone

Summarize

Perspective

Southwest of the Government Zone was the Food Zone, composed of 13 buildings in total (the Swedish and Turkish pavilions were physically within the Food Zone but were classified as being part of the Government Zone[210]). Its focal exhibit was Food No. 3, a rhomboidal structure with four shafts representing wheat stalks.[211][212] The Food Zone included the following buildings:

Remove ads

Production and Distribution Zone

Summarize

Perspective

The Production and Distribution Zone was dedicated to showcasing industries that specialized in manufacturing and distribution.[239][240] The focal exhibit was the Consumers Building (also the Consumer Interests Building),[241] which was renamed the World of Fashion during 1940.[35] The L-shaped structure was designed by Frederic C. Hirons and Peter Copeland, with murals by Francis Scott Bradford.[242] Numerous individual companies hosted exhibitions in this region. There were also pavilions dedicated to a generic industry, such as electrical products, industrial science, pharmaceuticals, metals, and men's apparel.[243] A hall of textiles was also built for the fair.[244]

Remove ads

Transportation Zone

Summarize

Perspective

The Transportation Zone was located west of the Theme Center, across the Grand Central Parkway.[281] The focal exhibit of the Transportation Zone was a Chrysler exhibit group designed by Raymond Loewy. In the focal exhibit, an audience could watch a Plymouth being assembled in an early 3D film in a theater with air conditioning, then a new technology.[282] Though the New York City Building was physically within the Transportation Zone, it was classified as part of the Government Zone.[283] Other buildings in the Transportation Zone included:

Remove ads

Amusement Area

Summarize

Perspective

The Amusement Area was located south of World's Fair Boulevard, along 230 acres (93 ha).[298][299] Unlike traditional fairgrounds, the Amusement Area at the 1939 Fair had no midway; instead, the fairground was divided into more than a dozen themed zones.[300][301] The Amusement Area contained numerous bars, restaurants, miniature villages, musical programs, dance floors, rides, and arcade attractions.[302][299] In general, the site was shaped like a horseshoe. The western shore of Fountain Lake contained Florida's pavilion and a military camp attraction,[299] while rides and concessions were mostly grouped around the eastern side of Fountain Lake.[299][298] There were also fireworks shows every night.[299] Many of the amusement rides were operated by either Harry C. Baker or Harry G. Traver, two prominent roller-coaster designers and operators.[303]

Due to the popularity of nude or seminude performances at the Golden Gate International Exposition, similar shows were presented in the Amusement Area.[302] A number of the shows provided spectators with the opportunity of viewing scantily clad or topless women.[304] Many of these "girl shows" were delayed due to construction issues and censorship laws in the United States,[305][306] and several shows were censored after they opened.[307] For the 1940 season, the area was rebranded as the "Great White Way", a reference to Broadway theatre.[35][267][308] During that season, the Amusement Area had 50 attractions in total; this consisted of 22 concessions, 12 rides, 12 eateries, three theatrical shows, and one fireworks show.[309]

Remove ads

Other exhibits

Summarize

Perspective

Standalone exhibits

There were two focal exhibits that were not located within any zone. The first was the Medical and Public Health Building on Constitution Mall and the Avenue of Patriots (immediately northeast of the Theme Center).[358] This structure contained a massive "Hall of Man" designed by I. Woodner-Silverman, which was dedicated to the human body, and a "Hall of Medical Science" designed by Otto Teegan, which was dedicated to medical professions and devices.[358][359] The first floor of the building had a 5,000-square-foot (460 m2) private club for medical professionals, with a lounge.[360]

The Science and Education Building, located on a curved portion of Hamilton Place between the Avenue of Patriots and Washington Square, just north of the Medical and Public Health Building. The building was not used to teach science, but it contained an auditorium and several exhibits on science and education.[361] The pavilion also had an exhibit on kindergartens during the 1940 season.[362]

Other structures

At the west end of the fairground was the administration building; this structure included a first-floor hall with artifacts about the fair, in addition to offices and a cafeteria.[363] The building's facade had a 27-foot-tall (8.2 m) relief of a woman.[364] During the fairground's construction, the administration building contained mockups of industry-themed exhibits,[365] and it was also used to test out lighting systems.[22] The fair also had a hospitality center staffed mainly by women, This building had an auditorium, lounge, restaurant, dressing rooms, lockers, and offices for national and international organizations.[366] Twenty American breweries operated the Hometown Restaurant, a 53,000-square-foot (4,900 m2) eatery with 2,000 seats and a 205-foot-long (62 m) bar.[367]

The fairground had a bank branch operated by Manufacturers Trust.[368][369] The bank branch had murals on its exterior and interior, as well as a 60-foot-wide (18 m) rotunda and a banking office.[369] There was also a Barclays Bank branch at the fair.[370]

Unbuilt exhibits

The original plans called for a veterans' temple of peace next to the state-themed buildings.[371] South of the Food Zone, there was originally supposed to be a fisheries building with a stadium.[372] The WFC had also announced plans for a "freedom pavilion" in January 1939, depicting Germany before the Nazi government takeover,[373] but the plans were abandoned because of a lack of time and money.[374] Syria withdrew plans for a pavilion in April 1939 due to internal unrest;[375] the proposed Hall of Fashion was canceled the same month, and the Hall of Fashion building was used as an event space.[376]

El Salvador was originally supposed to have a pavilion at the fair as well, but these plans were canceled in favor of a pavilion at the Golden Gate International Exposition.[377] In advance of the 1940 season, some of the state exhibits were expanded, while others were shuttered.[186] Some states considered hosting exhibits at the 1939 World's Fair before canceling their plans. Nevada's exhibit was canceled in June 1939 due to labor-related troubles,[378] and California scrapped plans for an exhibit after the New York State Legislature refused to provide funds for a New York state pavilion at the Golden Gate International Exposition.[379] Oregon withdrew from the fair due to disputes over where the Oregon pavilion would have been located.[380]

Remove ads

Preserved pavilions and attractions

Summarize

Perspective

The WFC mandated that almost all structures be removed within four months of the fair's closure.[11] The vast majority of structures were dismantled or moved shortly after the fair's final day.[381]

Seven structures were initially preserved as part of the park.[11][381][c] Among these was the Japan pavilion, which was dedicated in September 1940[382] but was razed the next year because it did not meet the city's building code.[383] The New Jersey pavilion was preserved as a headquarters for Flushing Meadows Park's police force.[384] The fair's New York City Building was used as a temporary headquarters for the United Nations General Assembly[385] before again becoming a pavilion for the 1964 fair;[386] it has housed the Queens Museum since 1972.[387] The New York City Subway's Willets Point station continued to serve Flushing Meadows Park after the fair,[388] and the LIRR's Willets Point station also remained open.[389] At the southern edge of the fairground, the Aquacade amphitheater remained standing until the 1990s.[390]

Many of the World's Fair amusement rides were sold to Luna Park at Coney Island;[391] the Parachute Jump was sold and relocated to Steeplechase Park, also in Coney Island.[392] One building from the fair's Town of Tomorrow exhibit was moved to New Jersey in 1955;[393] another building from that exhibit was turned into an office for the Queens Botanical Garden before it burned down in 1956.[394] The fair's Christian Science pavilion became the Church of Christ, Scientist, in Freeport, New York,[395] and the Belgian Building was dismantled and rebuilt at Virginia Union University in Richmond, Virginia.[396] Pieces of exhibits were also saved: A large portion of the General Motors pavilion's Futurama exhibit was displayed at Rockefeller Center's New York Museum of Science and Industry,[397] and the Ford Cycle of Production exhibit was moved to Dearborn, Michigan.[398] The Bendix Golden Temple was disassembled and placed in storage for many years, but various proposals to reconstruct it have failed.[399]

Remove ads

Critical reception

Summarize

Perspective

When the fair was being developed, The New York Times described the buildings as "a cross between functional architecture and fair architecture", with "undeniably spectacular" designs.[24] Lynn Hardesty of The Washington Post wrote that the buildings "have astonished even the most sophisticated of art critics" because they were so colorful.[29] Conversely, the critic Lewis Mumford lambasted the design of the fairground, calling it a "half-baked order of a Renaissance plan" that introduced disarray to the fair.[400][401] Talbot Hamlin regarded the WFC buildings as having "neither monumentality or gaiety",[20][21] though he believed that the individual exhibitors' pavilions were "in themselves interesting and beautiful".[402] Royal Cortissoz of the New York Herald Tribune felt that, although the fair's muralists were skilled, many of the murals on the buildings appeared to be "arbitrarily affixed", rather than essential components of the buildings' designs.[403]

When the fair opened, a writer for the Architectural Review said the WFC buildings lacked a logical design and that they did not give a light-hearted or imposing impression.[20] The architect Harvey Wiley Corbett saw the buildings as disharmonious, saying that "each building screams at the visitor in its own different voice"; according to Corbett, it was hard to derive any single conclusion from the fair as a result.[404] On the other hand, a New York Times writer said that the state and U.S. territory exhibit buildings were "in itself of outstanding interest".[170] A New York Herald Tribune writer, in mid-1939, wrote that the foreign exhibit buildings were "an absorbing and genuine display of the attractions all the countries offer".[405]

In 1964, one writer for The New York Times wrote that "the exhibits were appreciated for things their sponsors never suspected", since they provided places for guests to relax.[406] Design critic Paul Goldberger, writing about the fair in 1980, said "a coherent design nonetheless emerged", despite the frequent clashes between advocates of historical and Art Moderne architecture during the fair's development.[407]

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads