Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

2013 Malian presidential election

Presidential election held in Mali From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Presidential elections were held in Mali on 28 July 2013, with a second round run-off held on 11 August.[1] On his third bid, career politician Ibrahim Boubacar Keita of the Rally for Mali defeated Soumaïla Cissé in the run-off to become the new President of Mali. His victory was largely attributed to support from influential Islamist figures, primarily "people's imam" Mahmoud Dicko, as well as backing from the military, including the leaders of the 2012 coup. Keita's rise to power represented a continuation of the political establishment that had prevailed under former presidents Touré and Konaré.[2]

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

According to the 1992 constitution, elections should have taken place in 2012. The first round was originally scheduled for 29 April, and the second round scheduled for 13 May. The first round was also planned to include a referendum on revising the constitution.[3]

The elections would have marked the end of the second term of office of President Amadou Toumani Touré, conforming to the Malian constitution which limits individuals to two presidential terms. Touré confirmed, at a press conference on 12 June 2011, that he would not stand for election again.[4]

Rebellion

Since independence, pressures from government policies aimed at crushing traditional power structures, social mores, and local justice customs have caused several rebellions by the Tuaregs. Repeated promises of autonomy made in the aftermath of these uprisings were ignored, and Tuareg leaders were frequently sidelined from national politics.[5] By late 2010, Tuareg political activists were renewing calls for Azawadi independence,[6] asserting that they were marginalized and consequently impoverished in both Mali and Niger, and that mining projects had damaged important pastoral areas. Contributing to these grievances were broader issues such as climate change and a long history of forced modernization imposed on the nomadic societies of northern Mali, which deepened the divide between Tuareg communities and the central government.[7]

From February 2011, with the collapse of Gaddafi's Libya, hundreds of his Tuareg fighters, many veterans of the previous rebellions and now unemployed, returned to Mali with large stockpiles of weapons.[5] Rebels in the National Transitional Council also returned, driven by finacial reasons and the alleged racism of the NTC's fighters and militias.[8] Upon returning, they found that, despite past promises, little had changed in the relationship between their communities and the central government.[5]

In October 2011, the returning fighters began negotiations in Zakak with local leaders in the region, resulting in the formation of the secular-oriented National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), composed of these veterans and several other groups. Despite historically having difficulty maintaining alliances between secular and Islamist factions, on 10 January 2012, the MNLA and Ansar Dine, a jihadist group, came to an agreement to combine their forces in their upcoming rebellion.[6] Separately, Ansar Dine formed an alliance with other Salafi Islamist groups, including MOJWA and AQIM.[9] The MNLA was de facto allied with the other Jihadist groups.[10]

Starting on 16 January,[11] the MNLA began launching attacks against the disorganized and underresourced government forces in the cities of Ménaka, Aguelhok, and Tessalit.[6][2] In weeks, the rebels advanced to within 125 kilometers of Timbuktu, facing little resistance as they entered the towns of Diré and Goundam without a fight.[12] Ansar Dine stated that it had control of the Mali-Algeria border.[13]

Coup d'etat

On 21 March 2012, soldiers displeased with the management of the rebellion attacked several locations in the capital Bamako, including the presidential palace, state television, and military barracks.[14]

The next morning, Captain Amadou Sanogo, the chairman of the new National Committee for the Restoration of Democracy and State (CNRDR), made a statement in which he announced that the junta had suspended Mali's constitution and taken control of the nation.[15] The mutineers cited Touré's alleged poor handling of the insurgency and the lack of equipment for the Malian Army as their reasons for the rebellion.[16] The CNRDR would serve as an interim regime until power could be returned to a new, democratically elected government.[17]

While the coup was widely supported by population,[2] it was "unanimously condemned" by the international community,[18] including by the United Nations Security Council,[19] the African Union,[19] and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the latter of which on 27 March imposed sanctions, closed borders, and froze bank accounts, demanding that the coupers leave power before April 6th.[2]

During the uncertainty following the coup, resistance put up by government forces in the north began to melt away, allowing the rebels to take over the three provincial capitals of Timbuktu, Kidal, and Gao from 30 March to 1 April.[6] The speed and ease with which the rebels took control of the north was attributed in large part to the confusion created in the army's coup, leading Reuters to describe it as "a spectacular own-goal".[20] On 6 April 2012, stating that it had secured all of its desired territory, the MNLA declared independence from Mali, which was rejected as invalid by the African Union and the European Union.[21]

The same day, the junta and ECOWAS reached an agreement in which both Sanogo and Touré would resign, sanctions would be lifted, the mutineers would be granted amnesty, and power would pass to National Assembly of Mali Speaker Dioncounda Traoré.[22] Despite this de jure transistion, Sanogo seemed to remain the "real" head of state.[2]

Inter-rebel fighting, international intervention

As soon as independence was declared, tensions emerged between the MNLA and jihadist groups due to differences in goals with their common enemy defeated. Tuareg nationalists sought to maintain an independent state, while the jihadist wished to spread Islamic rule to the rest of Mali and neighboring states.[2] Attempts to find a solution failed, and soon conflict erupted between the MNLA and Jihadist, resulting in a decisive defeat for the MNLA. The jihadist groups seized control of nearly all of Azawad, with the exception of a few towns and isolated pockets still held by the MNLA and allied militias.[6]

Despite internal acknowledgment by jihadist leaders that they were too weak to expand,[2] on 10 January 2013, emirate forces captured the strategic town of Konna, 600 km from the capital, from the Malian army.[23] Later, an estimated 1,200 Islamist fighters advanced to within 20 kilometers of Mopti, a nearby Mali military garrison town.[24]

The rapid offensive forced Traoré to seek help from France, which ordered the deployment of 4,000 troops and significant quantities of military equipment to Mali the following day as part of Operation Serval, aimed at halting the Islamist advance and launching a counteroffensive.[2] On 1 July 2013, 6,000 of a future total of 12,600 UN peacekeeping troops officially took over responsibility for patrolling the country's north from France and the ECOWAS' International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA). The force would be led by former second-in-command in Darfur, Rwandan General Jean Bosco Kazura, and will be known as the MINUSMA. Though the group was expected to play a role in the election, the electoral commission's president, Mamadou Diamountani, said it would be "extremely difficult" to arrange for up to eight million voting identification cards when there were 500,000 displaced people as a result of the conflict.[25]

By the time of the election, thanks to French, African, and international military support, government forces had regained most of the territory previously controlled by Islamists and Tuareg nationalists.[2]

Remove ads

Electoral organisation controversies

Summarize

Perspective

To improve the electoral process, the government decided to use the election process of the Administrative Census to Elections (RACE) to further direct the Minister of Territorial Administration and Local Government and the General Administrator of Elections, General Kafougona Kone.[26] The majority of political parties would prefer the use of another electoral system under the Administrative Census Vocation of Civil Status (RAVEC), an electoral process considered more reliable. However, the government considers that this second process with RAVEC presents a number of difficulties with identification of non-Malians living in the Côte d'Ivoire and there are a large number of corrections to be made in a very short time.[27]

The cost of using this other process is estimated at 41 billion West African CFA francs (nearly $83 million US dollars).[28] At a meeting between the government and political parties on 3 January 2012, the National Director of the Interior, to the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Local Government, Bassidi Coulibaly, acknowledged the weak influence of citizens for revision of the electoral lists.[29]

Just as campaigning was about to get under way, the Malian government lifted the state of emergency in place in the country since the northern battles.[30]

Although the jihadist group MUJAO warned people not to vote and threatened to attack polling stations, no violence occurred during the elections.[31]

Remove ads

Candidates

Summarize

Perspective

Several candidates declared their intention to run for the original elections or were invested by their party.

- Jamille Bittar, senior vice president of the Party for Economic and Social Development of Mali (PDES), announced his presidential candidacy on 30 January 2012. He is the President of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry and he is on the Economic and Social Council and he is supported by the Union of movements and associations in Mali, created two months ago.[32]

- Sidibé Aminata Diallo, former Minister of Education, she was previously a candidate in the presidential election of 2007, and was supported for her candidacy on 24 December 2011 by the Rally for Environmental Education and Sustainable Development (REDD).[33]

- Cheick Modibo Diarra, Malian astrophysicist who worked at NASA and president of Microsoft Africa. On 6 March 2011, in Bamako, he presented a training policy, the Rally for Mali's development (RPDM), created for the 2012 presidential election.[34]

- Housseini Amion Guindo, President of Convergence for the development of Mali, was appointed on 14 September 2011 as presidential election candidate by the political group PUR (parties united for the Republic).[35]

- Mamadou Djigué, announced his candidacy on 22 September 2011 under the banner of the Youth Movement for Change and Development (MJCD). This announcement was made at a meeting held at the International Conference Centre of Bamako, in the presence of his father Ibrahima N'Diaye, Senior Vice President of the Alliance for Democracy in Mali-African Party for Solidarity and Justice.[36]

- Aïchata Cissé Haïdara, nicknamed Chato, is the presidential candidate from the Alliance Chato 2013 for the Malian election on July 28. The party's social and economic program,"For a Strong Mali," focuses on youth, women and the rural world. Currently the MP from Bourem in northern Mali, during the recent Malian crisis Chato distinguished herself in a fight against misinformation from the MNLA (National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, initially a Tuareg secessionist movement). Chato also worked for more than 20 years in the development of Mali in particular and of Africa in general. A union activist, she led a massive battle for Malian workers in Air Afrique; they were the only Africans to have been compensated after the firm was liquidated. Mme Haidara is a founder and managing director of a travel and tourism company, Wani Tour. [original research?]

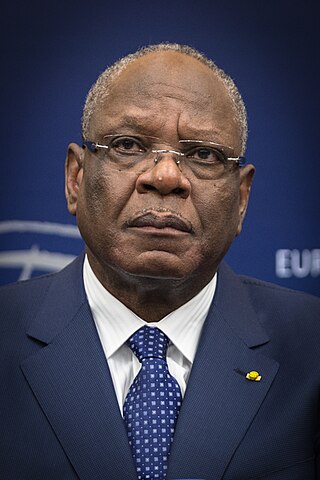

- Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, former Prime Minister of Mali, former speaker of the National Assembly, and president of the Rally for Mali (RPM), announced his candidacy on January 14, 2012.[37] He was a presidential candidate in the previous presidential elections of 2002 and 2007. He has the support of fifteen political parties that signed a memorandum of agreement on 12 January 2012 to "create a Republican and Democratic center that is strong and stable". The political parties are: Movement for the Independence, Renaissance and African Integration (Miria), the Union of Mali for Progress (UMP), the Malian Union-African Democratic Rally, the African Front for the mobilization and alternation (Fama), the Rally of Democratic Republicans (RDR), the Rally for Justice in Mali (RJD), Sigikafo Oyédamouyé Party (PSO), the Democratic Consultation, the Party of the difference in Mali (PDM), the Socialist and Democratic Party of Mali (PSDM), the People's Progress Party (PPP), the PPM, the MPLO, the RUP, the Democratic Action for Change and Alternative in Mali (ADCAM) and the Rally for Mali (RPM).[38]

- Aguibou Koné, former student leader, announced on 25 January 2012 that he would run for president in 2012 to defend the colours of a political organisation called "to Yèlè" (this means "to open" in the national language Bambara).[39][40]

- Oumar Mariko, Member of Parliament, was supported by the Party African Solidarity for Democracy and Independence on 26 June 2011. He has already been a candidate in the two previous presidential elections in 2002 and 2007. In his program, he wants to "build a strong democratic state, respectful of republican values, and equitable distribution of national resources".[41]

- Achérif Ag Mohamed was nominated on 12 November 2011 by the National Union for Labor and Development.[42]

- Soumana Sacko, former Prime Minister and President of the National Convention for Africa Solidarity (CNAS) declared his candidacy on 18 December 2011.[43]

- Yeah Samake, mayor of the rural town of Ouélessébougou, announced his candidacy for presidency on 12 November 2011 on behalf of the Party for the civic and patriotic (PACP), a new political party.[44] In reaction against alleged corruption of the other candidates, Samake is doing most of his fundraising online and in the United States.[citation needed]

- Modibo Sidibé, former Prime Minister, announced his candidacy on 17 January 2012.[45]

- Mountaga Tall was selected as a presidential candidate by the National Congress of Democratic Initiative (CNID) on 15 January 2012 in Bamako. The lawyer was a presidential candidate in 1992, 2002, and 2007.[46]

- Cheick Bougadary Traoré, president of the African Convergence for Renewal (CARE), was selected as a candidate of his party on 28 January 2012. Traore is the son of President Moussa Traoré.[47]

- Dramane Dembélé was designated as Adéma-PASJ's candidate on 10 April 2013.[48]

Remove ads

Results

Summarize

Perspective

On 3 August 2013, ADEMA candidate Dramane Dembélé, who placed third in the election, announced his support for Ibrahim Boubacar Keita in the second round, saying that "we are in the Socialist International, we share the same values". However, in endorsing Keita he contradicted the official stance of ADEMA, which had backed Keita's rival, Soumaïla Cissé, on the previous day. The party stressed that Dembélé was speaking only for himself and that the party still supported Cissé.[49]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads