Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Air conditioning

Cooling of air in an enclosed space From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C (US) or air con (UK),[1] is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior temperature and, in some cases, controlling the humidity of internal air. Air conditioning can be achieved using a mechanical 'air conditioner' or through other methods, such as passive cooling and ventilative cooling.[2][3] Air conditioning is a member of a family of systems and techniques that provide heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC).[4] Heat pumps are similar in many ways to air conditioners but use a reversing valve, allowing them to both heat and cool an enclosed space.[5]

There are various types of air conditioners. Popular examples include: Window-mounted air conditioner (China, 2023); Ceiling-mounted cassette air conditioner (China, 2023); Wall-mounted air conditioner (Japan, 2020); Ceiling-mounted console (Also called ceiling suspended) air conditioner (China, 2023); and portable air conditioner (Vatican City, 2018).

In hot weather, air conditioning can prevent heat stroke, dehydration due to excessive sweating, electrolyte imbalance, kidney failure, and other issues due to hyperthermia.[6][7][8] An estimated 190,000 heat-related deaths are averted annually owing to air conditioning.[9][10] Air conditioners increase productivity in hot climates, and historians rank air conditioning as a key factor that shaped postwar metropolitan growth, alongside highways, automobiles, shopping malls, and suburban housing.[11][12] As of 2022[update], air conditioning used about 7% of global electricity and emitted 3% of greenhouse gas.[13]

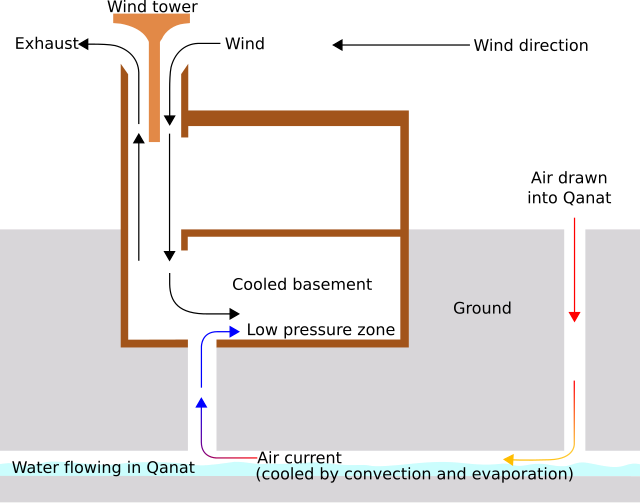

Air conditioners, which typically use vapor-compression refrigeration, range in size from small units used in vehicles or single rooms to massive units that can cool large buildings.[14] Air source heat pumps, which can be used for heating as well as cooling, are becoming increasingly common in cooler climates. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) 1.6 billion air conditioning units were used globally in 2016.[6] The United Nations has called for the technology to be made more sustainable to mitigate climate change and for the use of alternatives, like passive cooling, evaporative cooling, selective shading, windcatchers, and thermal insulation.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Air conditioning dates back to prehistory.[15] Double-walled living quarters, with a gap between the two walls to encourage air flow, were found in the ancient city of Hamoukar, in modern Syria.[16] Ancient Egyptian buildings also used a wide variety of passive air-conditioning techniques.[17] These became widespread from the Iberian Peninsula through North Africa, the Middle East, and Northern India.[18]

Passive techniques remained widespread until the 20th century when they fell out of fashion and were replaced by powered air conditioning. Using information from engineering studies of traditional buildings, passive techniques are being revived and modified for 21st-century architectural designs.[19][18]

Air conditioners allow the building's indoor environment to remain relatively constant, largely independent of changes in external weather conditions and internal heat loads. They also enable deep plan buildings to be created and have allowed people to live comfortably in hotter parts of the world.[20]

Development

Preceding discoveries

In 1558, Giambattista della Porta described a method of chilling ice to temperatures far below its freezing point by mixing it with potassium nitrate (then called "nitre") in his popular science book Natural Magic.[21][22][23] In 1620, Cornelis Drebbel demonstrated "Turning Summer into Winter" for James I of England, chilling part of the Great Hall of Westminster Abbey with an apparatus of troughs and vats.[24] Drebbel's contemporary Francis Bacon, like della Porta a believer in science communication, may not have been present at the demonstration, but in a book published later the same year, he described it as "experiment of artificial freezing" and said that "Nitre (or rather its spirit) is very cold, and hence nitre or salt when added to snow or ice intensifies the cold of the latter, the nitre by adding to its cold, but the salt by supplying activity to the cold of the snow."[21]

In 1758, Benjamin Franklin and John Hadley, a chemistry professor at the University of Cambridge, conducted experiments applying the principle of evaporation as a means to cool an object rapidly. Franklin and Hadley confirmed that the evaporation of highly volatile liquids (such as alcohol and ether) could be used to drive down the temperature of an object past the freezing point of water. They experimented with the bulb of a mercury-in-glass thermometer as their object. They used a bellows to speed up the evaporation. They lowered the temperature of the thermometer bulb down to −14 °C (7 °F) while the ambient temperature was 18 °C (64 °F). Franklin noted that soon after they passed the freezing point of water 0 °C (32 °F), a thin film of ice formed on the surface of the thermometer's bulb and that the ice mass was about 6 mm (1⁄4 in) thick when they stopped the experiment upon reaching −14 °C (7 °F). Franklin concluded: "From this experiment, one may see the possibility of freezing a man to death on a warm summer's day."[25]

The 19th century included many developments in compression technology. In 1820, English scientist and inventor Michael Faraday discovered that compressing and liquefying ammonia could chill air when the liquefied ammonia was allowed to evaporate.[26] In 1842, Florida physician John Gorrie used compressor technology to create ice, which he used to cool air for his patients in his hospital in Apalachicola, Florida. He hoped to eventually use his ice-making machine to regulate the temperature of buildings.[26][27] He envisioned centralized air conditioning that could cool entire cities. Gorrie was granted a patent in 1851,[28] but following the death of his main backer, he was not able to realize his invention.[29] In 1851, James Harrison created the first mechanical ice-making machine in Geelong, Australia, and was granted a patent for an ether vapor-compression refrigeration system in 1855 that produced three tons of ice per day.[30] In 1860, Harrison established a second ice company. He later entered the debate over competing against the American advantage of ice-refrigerated beef sales to the United Kingdom.[30]

First devices

Electricity made the development of effective units possible. In 1901, American inventor Willis H. Carrier built what is considered the first modern electrical air conditioning unit.[31][32][33][34] In 1902, he installed his first air-conditioning system in the Sackett-Wilhelms Lithographing & Publishing Company in Brooklyn, New York.[35] He patented "air conditioning" in 1906,[36] and by 1914, the first domestic (or "residential") air conditioning was installed.[26] His invention controlled both the temperature and humidity, which helped maintain consistent paper dimensions and ink alignment at the printing plant. Later, together with six other employees, Carrier formed The Carrier Air Conditioning Company of America, a business that in 2020, employed 53,000 people and was valued at $18.6 billion.[37][38]

In 1906, Stuart W. Cramer of Charlotte, North Carolina, was exploring ways to add moisture to the air in his textile mill. Cramer coined the term "air conditioning" in a patent claim which he filed that year, where he suggested that air conditioning was analogous to "water conditioning", then a well-known process for making textiles easier to process.[39] He combined moisture with ventilation to "condition" and change the air in the factories, thus controlling the humidity that is necessary in textile plants. Willis Carrier adopted the term and incorporated it into the name of his company.[40]

Domestic air conditioning soon took off. In 1914, the first domestic air conditioning was installed in Minneapolis in the home of Charles Gilbert Gates. It is, however, possible that the considerable device (c. 2.1 m × 1.8 m × 6.1 m; 7 ft × 6 ft × 20 ft) was never used, as the house remained uninhabited[26] (Gates had already died in October 1913.)

In 1931, H.H. Schultz and J.Q. Sherman developed what would become the most common type of individual room air conditioner: one designed to sit on a window ledge. The units went on sale in 1932 at US$10,000 to $50,000 (the equivalent of $200,000 to $1,200,000 in 2024.)[26] A year later, the first air conditioning systems for cars were offered for sale.[41] Chrysler Motors introduced the first practical semi-portable air conditioning unit in 1935,[42] and Packard became the first automobile manufacturer to offer an air conditioning unit in its cars in 1939.[43]

Further development

Innovations in the latter half of the 20th century allowed more ubiquitous air conditioner use. In 1945, Robert Sherman of Lynn, Massachusetts, invented a portable, in-window air conditioner that cooled, heated, humidified, dehumidified, and filtered the air.[44] The first inverter air conditioners were released in 1980–1981.[45][46]

In 1954, Ned Cole, a 1939 architecture graduate from the University of Texas at Austin, developed the first experimental "suburb" with inbuilt air conditioning in each house. 22 homes were developed on a flat, treeless track in northwest Austin, Texas, and the community was christened the 'Austin Air-Conditioned Village.' The residents were subjected to a year-long study of the effects of air conditioning led by the nation's premier air conditioning companies, builders, and social scientists. In addition, researchers from UT's Health Service and Psychology Department studied the effects on the "artificially cooled humans." One of the more amusing discoveries was that each family reported being troubled with scorpions, the leading theory being that scorpions sought cool, shady places. Other reported changes in lifestyle were that mothers baked more, families ate heavier foods, and they were more apt to choose hot drinks.[47][48]

Air conditioner adoption tends to increase above around $10,000 (circa 2021) annual household income in warmer areas.[49] Global GDP growth explains around 85% of increased air condition adoption by 2050, while the remaining 15% can be explained by climate change.[49]

Air conditioning linked to heat island effect

The urban heat island effect was first scientifically noted by Luke Howard in the 1810s, who described London being several degrees warmer than its rural surroundings at night. The phenomenon gained attention in the late 1960s, mainly in Japan and North America.[50][51]

From the late 1980s to early 2010s, studies began to link air conditioners to the urban heat island effect.[52][53][54] The phenomenon was observed in various cities such as Tokyo and Houston.

Remove ads

Use by region

Summarize

Perspective

As of 2016[update], an estimated 1.6 billion air conditioning units were used worldwide, with over half of them in China and the United States, and with a total cooling capacity of 11,675 gigawatts.[55] The International Energy Agency predicted in 2018 that the number of air conditioning units would grow to around 4 billion units by 2050 and that the total cooling capacity would grow to around 23,000 GW, with the biggest increases in India and China.[6]

Asia

Between 1995 and 2004, the proportion of urban households in China with air conditioners increased from 8% to 70%.[56] Between 2010 and 2023, air conditioner use in India tripled to 24 units per 100 households,[57] with the most ownership in Haryana, Chandigarh, Rajasthan, and Delhi and the least in Meghalaya, Tripura, Manipur, and Himachal Pradesh.[58]

North America

As of 2015[update], nearly 100 million homes in the United States, or about 87% of US households, had air conditioning systems.[59] In 2019, it was estimated that 90% of new single-family homes constructed in the US included air conditioning, ranging from 99% in the South to 62% in the West.[60][61]

Europe

As of 2025[update], roughly half of homes in Italy, 40 percent of homes in Spain, and 20 to 25 percent of homes in France had air conditioning.[62]

Remove ads

Operation

Summarize

Perspective

Operating principles

Cooling in traditional air conditioner systems is accomplished using the vapor-compression cycle, which uses a refrigerant's forced circulation and phase change between gas and liquid to transfer heat.[63][64] The vapor-compression cycle can occur within a unitary, or packaged piece of equipment, or within a chiller that is connected to terminal cooling equipment (such as a fan coil unit in an air handler) on its evaporator side and heat rejection equipment such as a cooling tower on its condenser side. An air source heat pump shares many components with an air conditioning system, but includes a reversing valve, which allows the unit to be used to heat as well as cool a space.[65]

Air conditioning equipment will reduce the absolute humidity of the air processed by the system if the surface of the evaporator coil is significantly cooler than the dew point of the surrounding air. An air conditioner designed for an occupied space will typically achieve a 30% to 60% relative humidity in the occupied space.[66]

Most modern air-conditioning systems feature a dehumidification mode, in which the compressor runs. At the same time, the fan is slowed to reduce the evaporator temperature and condense more water. A dehumidifier uses the same refrigeration cycle but incorporates both the evaporator and the condenser into the same air path; the air first passes over the evaporator coil, where it is cooled[67] and dehumidified, before passing over the condenser coil, where it is warmed again before it is released back into the room.[citation needed]

Free cooling can sometimes be selected when the external air is cooler than the internal air. In this case, the compressor does not need to be used, resulting in high cooling efficiencies for these times. This may also be combined with seasonal thermal energy storage.[68]

Heating

Some air conditioning systems can reverse the refrigeration cycle and act as an air source heat pump, thus heating instead of cooling the indoor environment. They are also commonly referred to as "reverse cycle air conditioners". The heat pump is significantly more energy-efficient than electric resistance heating, because it moves energy from air or groundwater to the heated space and the heat from purchased electrical energy. When the heat pump is in heating mode, the indoor evaporator coil switches roles and becomes the condenser coil, producing heat. The outdoor condenser unit also switches roles to serve as the evaporator and discharges cold air (colder than the ambient outdoor air).

Most air source heat pumps become less efficient in outdoor temperatures lower than 4 °C or 40 °F.[69] This is partly because ice forms on the outdoor unit's heat exchanger coil, which blocks air flow over the coil. To compensate for this, the heat pump system must temporarily switch back into the regular air conditioning mode to switch the outdoor evaporator coil back to the condenser coil, to heat up and defrost. Therefore, some heat pump systems will have electric resistance heating in the indoor air path that is activated only in this mode to compensate for the temporary indoor air cooling, which would otherwise be uncomfortable in the winter.

Newer models have improved cold-weather performance, with efficient heating capacity down to −14 °F (−26 °C).[70][69][71] However, there is always a chance that the humidity that condenses on the heat exchanger of the outdoor unit could freeze, even in models that have improved cold-weather performance, requiring a defrosting cycle to be performed.

Heat pumping capacity declines as temperature difference increases, while at the same time heating needs increase, so heat pumps are sometimes installed in tandem with a more conventional form of heating, such as an electrical heater, a natural gas, heating oil, or wood-burning fireplace or central heating, which is used instead of or in addition to the heat pump during harsher winter temperatures. In this case, the heat pump is used efficiently during milder temperatures, and the system is switched to the conventional heat source when the outdoor temperature is lower.

Performance

The coefficient of performance (COP) of an air conditioning system is a ratio of useful heating or cooling provided to the work required.[72][73] Higher COPs equate to lower operating costs. The COP usually exceeds 1; however, the exact value is highly dependent on operating conditions, especially absolute temperature and relative temperature between sink and system, and is often graphed or averaged against expected conditions.[74] Air conditioner equipment power in the U.S. is often described in terms of "tons of refrigeration", with each approximately equal to the cooling power of one short ton (2,000 pounds (910 kg) of ice melting in a 24-hour period. The value is equal to 12,000 BTUIT per hour, or 3,517 watts.[75] Residential central air systems are usually from 1 to 5 tons (3.5 to 18 kW) in capacity.[citation needed]

The efficiency of air conditioners is often rated by the seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER), which is defined by the Air Conditioning, Heating and Refrigeration Institute in its 2008 standard AHRI 210/240, Performance Rating of Unitary Air-Conditioning and Air-Source Heat Pump Equipment.[76] A similar standard is the European seasonal energy efficiency ratio (ESEER).[citation needed]

Efficiency is strongly affected by the humidity of the air to be cooled. Dehumidifying the air before attempting to cool it can reduce subsequent cooling costs by as much as 90 percent. Thus, reducing dehumidifying costs can materially affect overall air conditioning costs.[77]

Remove ads

Control system

Summarize

Perspective

Wireless remote control

A wireless remote controller

The infrared transmitting LED on the remote

The infrared receiver on the air conditioner

This type of controller uses an infrared LED to relay commands from a remote control to the air conditioner. The output of the infrared LED (like that of any infrared remote) is invisible to the human eye because its wavelength is beyond the range of visible light (940 nm). This system is commonly used on mini-split air conditioners because it is simple and portable. Some window and ducted central air conditioners uses it as well.

Wired controller

A wired controller, also called a "wired thermostat," is a device that controls an air conditioner by switching heating or cooling on or off. It uses different sensors to measure temperatures and actuate control operations. Mechanical thermostats commonly use bimetallic strips, converting a temperature change into mechanical displacement, to actuate control of the air conditioner. Electronic thermostats, instead, use a thermistor or other semiconductor sensor, processing temperature change as electronic signals to control the air conditioner.

These controllers are usually used in apartments, hospitals, offices and hotel rooms, because they are permanently installed into a wall and hard-wired directly into the air conditioner unit, eliminating the need for batteries.

Remove ads

Types

Summarize

Perspective

* where the typical capacity is in kilowatt as follows:

- very small: <1.5 kW

- small: 1.5–3.5 kW

- medium: 4.2–7.1 kW

- large: 7.2–14 kW

- very large: >14 kW

Mini-split and multi-split systems

Ductless systems (often mini-split, though there are now ducted mini-split) typically supply conditioned and heated air to a single or a few rooms of a building, without ducts and in a decentralized manner.[78] Multi-zone or multi-split systems are a common application of ductless systems and allow up to eight rooms (zones or locations) to be conditioned independently from each other, each with its indoor unit and simultaneously from a single outdoor unit.

The first mini-split system was sold in 1961 by Toshiba in Japan, and the first wall-mounted mini-split air conditioner was sold in 1968 in Japan by Mitsubishi Electric, where small home sizes motivated their development. The Mitsubishi model was the first air conditioner with a cross-flow fan.[79][80][81] In 1969, the first mini-split air conditioner was sold in the US.[82] Multi-zone ductless systems were invented by Daikin in 1973, and variable refrigerant flow systems (which can be thought of as larger multi-split systems) were also invented by Daikin in 1982. Both were first sold in Japan.[83] Variable refrigerant flow systems when compared with central plant cooling from an air handler, eliminate the need for large cool air ducts, air handlers, and chillers; instead cool refrigerant is transported through much smaller pipes to the indoor units in the spaces to be conditioned, thus allowing for less space above dropped ceilings and a lower structural impact, while also allowing for more individual and independent temperature control of spaces. The outdoor and indoor units can be spread across the building.[84] Variable refrigerant flow indoor units can also be turned off individually in unused spaces.[citation needed] The lower start-up power of VRF's DC inverter compressors and their inherent DC power requirements also allow VRF solar-powered heat pumps to be run using DC-providing solar panels.

Ducted central systems

Split-system central air conditioners consist of two heat exchangers, an outside unit (the condenser) from which heat is rejected to the environment and an internal heat exchanger (the evaporator, or Fan Coil Unit, FCU) with the piped refrigerant being circulated between the two. The FCU is then connected to the spaces to be cooled by ventilation ducts.[85] Floor standing air conditioners are similar to this type of air conditioner but sit within spaces that need cooling.

Central plant cooling

Large central cooling plants may use intermediate coolant such as chilled water pumped into air handlers or fan coil units near or in the spaces to be cooled which then duct or deliver cold air into the spaces to be conditioned, rather than ducting cold air directly to these spaces from the plant, which is not done due to the low density and heat capacity of air, which would require impractically large ducts. The chilled water is cooled by chillers in the plant, which uses a refrigeration cycle to cool water, often transferring its heat to the atmosphere even in liquid-cooled chillers through the use of cooling towers. Chillers may be air or liquid cooled.[86][87]

Portable units

A portable system has an indoor unit on wheels connected to an outdoor unit via flexible pipes, similar to a permanently fixed installed unit (such as a ductless split air conditioner).

Hose systems, which can be monoblock or air-to-air, are vented to the outside via air ducts. The monoblock type collects the water in a bucket or tray and stops when full. The air-to-air type re-evaporates the water, discharges it through the ducted hose, and can run continuously. Many but not all portable units draw indoor air and expel it outdoors through a single duct, negatively impacting their overall cooling efficiency.

Many portable air conditioners come with heat as well as a dehumidification function.[88]

Window unit and packaged terminal

The packaged terminal air conditioner (PTAC), through-the-wall, and window air conditioners are similar. These units are installed on a window frame or on a wall opening. The unit usually has an internal partition separating its indoor and outdoor sides, which contain the unit's condenser and evaporator, respectively. PTAC systems may be adapted to provide heating in cold weather, either directly by using an electric strip, gas, or other heaters, or by reversing the refrigerant flow to heat the interior and draw heat from the exterior air, converting the air conditioner into a heat pump. They may be installed in a wall opening with the help of a special sleeve on the wall and a custom grill that is flush with the wall and window air conditioners can also be installed in a window, but without a custom grill.[89]

Packaged air conditioner

Packaged air conditioners (also known as self-contained units)[90][91] are central systems that integrate into a single housing all the components of a split central system, and deliver air, possibly through ducts, to the spaces to be cooled. Depending on their construction they may be outdoors or indoors, on roofs (rooftop units),[92][93] draw the air to be conditioned from inside or outside a building and be water or air-cooled. Often, outdoor units are air-cooled while indoor units are liquid-cooled using a cooling tower.[85][94][95][96][97][98]

Remove ads

Types of compressors

Summarize

Perspective

Reciprocating

This compressor consists of a crankcase, crankshaft, piston rod, piston, piston ring, cylinder head and valves. [citation needed]

Scroll

This compressor uses two interleaving scrolls to compress the refrigerant.[99] it consists of one fixed and one orbiting scrolls. This type of compressor is more efficient because it has 70 percent less moving parts than a reciprocating compressor. [citation needed]

Screw

This compressor use two very closely meshing spiral rotors to compress the gas. The gas enters at the suction side and moves through the threads as the screws rotate. The meshing rotors force the gas through the compressor, and the gas exits at the end of the screws. The working area is the inter-lobe volume between the male and female rotors. It is larger at the intake end, and decreases along the length of the rotors until the exhaust port. This change in volume is the compression. [citation needed]

Remove ads

Capacity modulation technologies

Summarize

Perspective

There are several ways to modulate the cooling capacity in refrigeration or air conditioning and heating systems. The most common in air conditioning are: on-off cycling, hot gas bypass, use or not of liquid injection, manifold configurations of multiple compressors, mechanical modulation (also called digital), and inverter technology. [citation needed]

Hot gas bypass

Hot gas bypass involves injecting a quantity of gas from discharge to the suction side. The compressor will keep operating at the same speed, but due to the bypass, the refrigerant mass flow circulating with the system is reduced, and thus the cooling capacity. This naturally causes the compressor to run uselessly during the periods when the bypass is operating. The turn down capacity varies between 0 and 100%.[100]

Manifold configurations

Several compressors can be installed in the system to provide the peak cooling capacity. Each compressor can run or not in order to stage the cooling capacity of the unit. The turn down capacity is either 0/33/66 or 100% for a trio configuration and either 0/50 or 100% for a tandem.[citation needed]

Mechanically modulated compressor

This internal mechanical capacity modulation is based on periodic compression process with a control valve, the two scroll set move apart stopping the compression for a given time period. This method varies refrigerant flow by changing the average time of compression, but not the actual speed of the motor. Despite an excellent turndown ratio – from 10 to 100% of the cooling capacity, mechanically modulated scrolls have high energy consumption as the motor continuously runs.[citation needed]

Variable-speed compressor

This system uses a variable-frequency drive (also called an Inverter) to control the speed of the compressor. The refrigerant flow rate is changed by the change in the speed of the compressor. The turn down ratio depends on the system configuration and manufacturer. It modulates from 15 or 25% up to 100% at full capacity with a single inverter from 12 to 100% with a hybrid tandem. This method is the most efficient way to modulate an air conditioner's capacity. It is up to 58% more efficient than a fixed speed system.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Impact

Summarize

Perspective

Health effects

In hot weather, air conditioning can prevent heat stroke, dehydration due to excessive sweating, electrolyte imbalance, kidney failure, and other issues due to hyperthermia.[6][7] Heat waves are the most lethal type of weather phenomenon in the United States.[101][102] A 2020 study found that areas with lower use of air conditioning correlated with higher rates of heat-related mortality and hospitalizations.[103] The August 2003 France heatwave resulted in approximately 15,000 deaths, where 80% of the victims were over 75 years old. In response, the French government required all retirement homes to have at least one air-conditioned room at 25 °C (77 °F) per floor during heatwaves.[6]

A 2021 report estimated that around 345,000 people aged 65 and older died in 2019 from the heat, which is preventable with air conditioning. An estimated 190,000 heat-related deaths are averted annually owing to air conditioning.[9][10]

Air conditioning (including filtration, humidification, cooling and disinfection) can be used to provide a clean, safe, hypoallergenic atmosphere in hospital operating rooms and other environments where proper atmosphere is critical to patient safety and well-being. It is sometimes recommended for home use by people with allergies, especially mold.[104][105] However, poorly maintained water cooling towers can promote the growth and spread of microorganisms such as Legionella pneumophila, the infectious agent responsible for Legionnaires' disease. As long as the cooling tower is kept clean (usually by means of a chlorine treatment), these health hazards can be avoided or reduced. The state of New York has codified requirements for registration, maintenance, and testing of cooling towers to protect against Legionella.[106]

Economic effects

First designed to benefit targeted industries such as the press as well as large factories, the invention quickly spread to public agencies and administrations with studies with claims of increased productivity close to 24% in places equipped with air conditioning.[11]

Air conditioning contributed to the economic development of the American South after the 1950s by enabling industrial activities in hot climates and supporting the expansion of white-collar work in cooled office spaces. It also influenced urban sprawl and commuting patterns, as air-conditioned vehicles made suburban development more viable. Historians rank air conditioning among key factors shaping postwar metropolitan growth, alongside highways, automobiles, shopping malls, and suburban housing.[12]

Air conditioning caused various shifts in demography, notably that of the United States starting from the 1970s. In the US, the birth rate was lower in the spring than during other seasons until the 1970s but this difference then declined since then.[107] As of 2007[update], the Sun Belt contained 30% of the total US population while it was inhabited by 24% of Americans at the beginning of the 20th century.[108] Moreover, the summer mortality rate in the US, which had been higher in regions subject to a heat wave during the summer, also evened out.[8]

The spread of the use of air conditioning acts as a main driver for the growth of global demand of electricity.[109] According to a 2018 report from the International Energy Agency (IEA), it was revealed that the energy consumption for cooling in the United States, involving 328 million Americans, surpasses the combined energy consumption of 4.4 billion people in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia (excluding China).[6] A 2020 survey found that an estimated 88% of all US households use AC, increasing to 93% when solely looking at homes built between 2010 and 2020.[110]

Environmental effects

Air conditioning used about 7% of global electricity in 2022, and emitted 3% of greenhouse gas.[13] A 2018 report on air conditioning efficiency by the International Energy Agency predicted an increase of electricity usage due to space cooling to around 6200 TWh by 2050,[6][111] and that with the progress currently seen, greenhouse gas emissions attributable to space cooling would double from 1,135 million tons (2016) to 2,070 million tons.[6] There is some push to increase the energy efficiency of air conditioners. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the IEA found that if air conditioners could be twice as effective as now, 460 billion tons of GHG could be cut over 40 years.[112] The UNEP and IEA also recommended legislation to decrease the use of hydrofluorocarbons, better building insulation, and more sustainable temperature-controlled food supply chains going forward.[112]

Refrigerants have also caused and continue to cause serious environmental issues, including ozone depletion and climate change, as several countries have not yet ratified the Kigali Amendment to reduce the consumption and production of hydrofluorocarbons.[113] CFCs and HCFCs refrigerants such as R-12 and R-22, respectively, used within air conditioners have caused damage to the ozone layer,[114] and hydrofluorocarbon refrigerants such as R-410A and R-404A, which were designed to replace CFCs and HCFCs, are instead exacerbating climate change.[115] Both issues happen due to the venting of refrigerant to the atmosphere, such as during repairs. HFO refrigerants, used in some if not most new equipment, solve both issues with an ozone damage potential (ODP) of zero and a much lower global warming potential (GWP) in the single or double digits vs. the three or four digits of hydrofluorocarbons.[116]

Hydrofluorocarbons would have raised global temperatures by around 0.3–0.5 °C (0.5–0.9 °F) by 2100 without the Kigali Amendment. With the Kigali Amendment, the increase of global temperatures by 2100 due to hydrofluorocarbons is predicted to be around 0.06 °C (0.1 °F).[117]

Air conditioning units also contribute to pollution as they are difficult to disassemble or repair. Separating metal and plastic at the end of a unit's life cycle is also costly and not practical, meaning units are frequently disposed of.[10]

Several journalists say it is an air conditioning paradox that arises from the usage of air conditioners to adapt to the effects of climate change, leading to higher energy consumption and heat generation as a byproduct, thereby exacerbating the problem.[118][119][120] The paradox is particularly concerning in emerging economies. While air conditioning has become a symbol of modernity and comfort, its widespread adoption could significantly increase global carbon emissions, undermining efforts to limit global warming.

Mitigation of some environmental drawbacks

Alternatives are currently being explored by governments and researchers, such as more energy-efficient systems, passive cooling techniques, and the development of low-GWP refrigerants. However, balancing the demand for cooling with the need to reduce carbon footprints remains a complex and pressing issue.[121][119]

As renewable energy becomes cheaper[122] and more popular, the energy source of air conditioners is shifting towards more renewable energy sources.[119] This reduces the amount of carbon emissions resulting directly from generating electricity.

The danger of high-GWP refrigerants, such as HFCs, escaping into the atmosphere and trapping heat can be mitigated through development of low-GWP refrigerants.[9]

Social and cultural effects

Socioeconomic groups with a household income below around $10,000 (circa 2021) tend to have a low air conditioning adoption,[49] which worsens heat-related mortality.[8] The lack of cooling can be hazardous, as areas with lower use of air conditioning correlate with higher rates of heat-related mortality and hospitalizations.[103] Premature mortality in NYC is projected to grow between 47% and 95% in 30 years, with lower-income and vulnerable populations most at risk.[103] Studies on the correlation between heat-related mortality and hospitalizations and living in low socioeconomic locations can be traced in Phoenix, Arizona,[123] Hong Kong,[124] China,[124] Japan,[125] and Italy.[126][127] Additionally, costs concerning health care can act as another barrier, as the lack of private health insurance during a 2009 heat wave in Australia, was associated with heat-related hospitalization.[127]

Disparities in socioeconomic status and access to air conditioning are connected by some to institutionalized racism, which leads to the association of specific marginalized communities with lower economic status, poorer health, residing in hotter neighborhoods, engaging in physically demanding labor, and experiencing limited access to cooling technologies such as air conditioning.[127] A study examining the US cities of Chicago, Detroit, Minneapolis, and Pittsburgh found that black households were half as likely to have central air conditioning units when compared to their white counterparts.[128] Especially in cities, redlining and other historical practices mean that racial disparities are also played out in heat islands, increasing temperatures in certain parts of the city.[127] This is due to heat-absorbing building materials and pavements and lack of vegetation and shade coverage.[129] There have been initiatives that provide cooling solutions to low-income communities, such as public cooling spaces.[6][129]

Cooling has allowed for growth of indoor home space and encouraged people, including children, to stay indoors more often.[130] It has also created uniformity of different geographical areas and climate zones.[131]

Remove ads

Alternative options for cooling

Summarize

Perspective

Alternatives to continual air conditioning include passive cooling, passive solar cooling, natural ventilation, operating shades to reduce solar gain, using trees, architectural shades, windows (and using window coatings) to reduce solar gain.[citation needed]

Buildings designed with passive air conditioning are generally less expensive to construct and maintain than buildings with conventional HVAC systems with lower energy demands.[132] While tens of air changes per hour, and cooling of tens of degrees, can be achieved with passive methods, site-specific microclimate must be taken into account, complicating building design.[18]

Many techniques can be used to increase comfort and reduce the temperature in buildings. These include evaporative cooling, selective shading, wind, thermal convection, and heat storage.[133]

Passive ventilation

Passive ventilation is the process of supplying air to and removing air from an indoor space without using mechanical systems. It refers to the flow of external air to an indoor space as a result of pressure differences arising from natural forces.

There are two types of natural ventilation occurring in buildings: wind driven ventilation and buoyancy-driven ventilation. Wind driven ventilation arises from the different pressures created by wind around a building or structure, and openings being formed on the perimeter which then permit flow through the building. Buoyancy-driven ventilation occurs as a result of the directional buoyancy force that results from temperature differences between the interior and exterior.[134]

Since the internal heat gains which create temperature differences between the interior and exterior are created by natural processes, including the heat from people, and wind effects are variable, naturally ventilated buildings are sometimes called "breathing buildings".Natural solutions

Natural solutions do not require energy for cooling purposes, and are therefore a very attractive solution. Many ways to achieve this have been explored.

The structure of a building can help dissipate heat. For example, in Zimbabwe, Eastgate Development cut its energy use by 90% by utilizing termite mound inspired structures.[119]

Coverage of windows can help reduce internal heat gain from sunlight. The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that window awnings can lower internal heat gain from sunlight by up to 77%.[119]

The coating of roofs have also seen great success. In the United States, painting roofs white has been shown to lower roof temperatures by as much as 30 °C. Meanwhile, in China, a project involving the installation of green roofs — roofs covered with vegetation — not only reduced the cooling demands of buildings, but also lowered the average land surface temperature in the area by 0.91 °C.[119]

Planting trees can also help mitigate the heat island effect. A study in Europe discovered that tree cover can reduce land surface temperatures in cities by as much as 12 °C during the summer. In the United States, another study found that when tree cover reaches 40%, ground-level temperatures were lowered by nearly 6 °C.[119]

Passive cooling

Passive cooling is a building design approach that focuses on heat gain control and heat dissipation in a building in order to improve the indoor thermal comfort with low or no energy consumption.[135][136] This approach works either by preventing heat from entering the interior (heat gain prevention) or by removing heat from the building (natural cooling).[137]

Natural cooling utilizes on-site energy, available from the natural environment, combined with the architectural design of building components (e.g. building envelope), rather than mechanical systems to dissipate heat.[138] Therefore, natural cooling depends not only on the architectural design of the building but on how the site's natural resources are used as heat sinks (i.e. everything that absorbs or dissipates heat). Examples of on-site heat sinks are the upper atmosphere (night sky), the outdoor air (wind), and the earth/soil.

Passive cooling is an important tool for design of buildings for climate change adaptation – reducing dependency on energy-intensive air conditioning in warming environments.[139][140]

Daytime radiative cooling

Passive daytime radiative cooling (PDRC) surfaces reflect incoming solar radiation and heat back into outer space through the infrared window for cooling during the daytime. Daytime radiative cooling became possible with the ability to suppress solar heating using photonic structures, which emerged through a study by Raman et al. (2014).[142] PDRCs can come in a variety of forms, including paint coatings and films, that are designed to be high in solar reflectance and thermal emittance.[141][143]

PDRC applications on building roofs and envelopes have demonstrated significant decreases in energy consumption and costs.[143] In suburban single-family residential areas, PDRC application on roofs can potentially lower energy costs by 26% to 46%.[144] PDRCs are predicted to show a market size of ~$27 billion for indoor space cooling by 2025 and have undergone a surge in research and development since the 2010s.[145][146]

Fans

Hand fans have existed since prehistory. Large human-powered fans built into buildings include the punkah.

The 2nd-century Chinese inventor Ding Huan of the Han dynasty invented a rotary fan for air conditioning, with seven wheels 3 m (10 ft) in diameter and manually powered by prisoners.[147]: 99, 151, 233 In 747, Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–762) of the Tang dynasty (618–907) had the Cool Hall (Liang Dian 涼殿) built in the imperial palace, which the Tang Yulin describes as having water-powered fan wheels for air conditioning as well as rising jet streams of water from fountains. During the subsequent Song dynasty (960–1279), written sources mentioned the air conditioning rotary fan as even more widely used.[147]: 134, 151

Thermal buffering

In areas that are cold at night or in winter, heat storage is used. Heat may be stored in earth or masonry; air is drawn past the masonry to heat or cool it.[19]

In areas that are below freezing at night in winter, snow and ice can be collected and stored in ice houses for later use in cooling.[19] This technique is over 3,700 years old in the Middle East.[148] Harvesting outdoor ice during winter and transporting and storing for use in summer was practiced by wealthy Europeans in the early 1600s,[21] and became popular in Europe and the Americas towards the end of the 1600s.[149] This practice was replaced by mechanical compression-cycle icemakers.

Evaporative cooling

In dry, hot climates, the evaporative cooling effect may be used by placing water at the air intake, such that the draft draws air over water and then into the house. For this reason, it is sometimes said that the fountain, in the architecture of hot, arid climates, is like the fireplace in the architecture of cold climates.[17] Evaporative cooling also makes the air more humid, which can be beneficial in a dry desert climate.[150]

Evaporative coolers tend to feel as if they are not working during times of high humidity, when there is not much dry air with which the coolers can work to make the air as cool as possible for dwelling occupants. Unlike other types of air conditioners, evaporative coolers rely on the outside air to be channeled through cooler pads that cool the air before it reaches the inside of a house through its air duct system; this cooled outside air must be allowed to push the warmer air within the house out through an exhaust opening such as an open door or window.[151]

Remove ads

Political debate

There is a longstanding political controversy about air conditioning, particularly in the nations of Europe, where the technology is relatively unadopted. The strongest opposition generally originates from environmentalists, European federalists, and left-wing parties, while supporters tend to be from the political right.[152][153]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads