Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

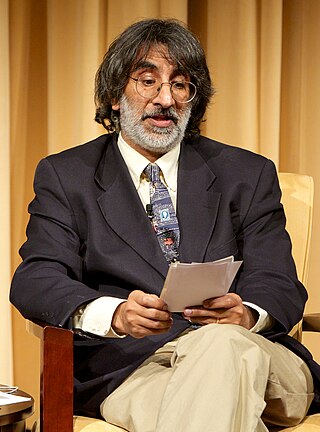

Akhil Reed Amar

American legal scholar (born 1958) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Akhil Reed Amar (born September 6, 1958) is an American legal scholar known for his expertise in U.S. constitutional law. He is a Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale University, where he is a leading scholar of originalism, the U.S. Bill of Rights, and criminal procedure.[1] He is Yale’s only living professor to have won the University’s unofficial triple crown—a Sterling Chair for scholarship, the DeVane Medal for teaching, and the Lamar Award for alumni service.[2]

Born in Michigan and raised in California, Amar was an undergraduate at Yale College before receiving his legal education at Yale Law School. He clerked for Judge (later Justice) Stephen Breyer and then became a junior professor at Yale Law School at the age of 26.[citation needed]

Amar has engaged with the American Bar Association and the Federalist Society, with his work receiving awards from both organizations.[3] According to a landmark 2021 study of lifetime scholarly citations by Fred R. Shapiro, Amar is the second most-cited American legal scholar still under age 70.[4][2] His work has been cited in more than fifty U.S. Supreme Court cases by justices appointed by both parties, the highest among living scholars under age 70.[2]

Remove ads

Early life and education

Summarize

Perspective

Amar was born on September 6, 1958, in Ann Arbor, Michigan.[5] He has two brothers, one of whom is Vikram Amar, who is also a legal scholar and was the dean of the University of Illinois College of Law.[6] His parents were young physicians from India who met at the University of Michigan.[5] His father became a professor at the University of California, San Francisco.[5] His middle name comes from his father's mentor, Reed M. Nesbit.[5]

Amar grew up in Walnut Creek, California, and graduated from Las Lomas High School in 1976.[7] He then attended Yale University, where he double majored in history and economics.[1] He was a member of the Yale Debate Association, winning its Thacher Memorial Prize, and was chair of the Liberal Party of the Yale Political Union.[8] He befriended future journalist Richard Brookhiser in his first year in college,[5] and graduated as a resident of Ezra Stiles College.[9] Amar graduated from Yale in 1980 with a Bachelor of Arts, summa cum laude, with membership in Phi Beta Kappa.[8] He had developed a serious interest in history studying under professors Edmund Morgan and John Morton Blum.[5]

In 1981, Amar entered Yale Law School, where he was an editor of The Yale Law Journal and had Robert Bork as a teacher.[8][5] He graduated in 1984 with a Juris Doctor degree. After law school, Amar was a law clerk for then-judge Stephen Breyer of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit from 1984 to 1985.[8] He interviewed for a clerkship with Justice John Paul Stevens but did not receive an offer.

Remove ads

Academic career

Summarize

Perspective

Amar joined the faculty of Yale Law School in 1985 as an assistant professor, then became an associate professor in 1988 and a full professor in 1990. From 1993 to 2008, he was the law school's Southmayd Professor of Law. He received the school's appointment as a Sterling Professor of Law in 2008.[8] Amar's former students include four U.S. senators—Cory Booker, Michael Bennet, Chris Coons, and Josh Hawley—and government officials Jake Sullivan and Neal Katyal.[10] Justice Brett Kavanaugh was also briefly a student of Amar.[11]

He is the author of many articles and books, including The Words That Made Us: America's Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840 and its sequel Born Equal: Remaking America's Constitution, 1840-1920. His nonfiction books have collectively earned two starred reviews from Publishers Weekly and three starred reviews from Kirkus Reviews.[12][13]

He was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2007.[14] In 2008, U.S. presidential candidate Mike Gravel said that he would name Amar to the Supreme Court if elected president.[15]

He was awarded the prestigious Barry Prize for Distinguished Intellectual Achievement by the American Academy of Sciences and Letters in 2024.[16]

Amar, a self-described liberal, has since engaged in advocacy considered controversial among progressive outlets, bloggers, and professors.[17][18][19] He argued in favor of Brett Kavanaugh's appointment to the Supreme Court[20] and argued that overturning Roe v. Wade would not affect other privacy rights.[21]

Since early 2021 he has co-hosted a weekly podcast, Amarica’s Constitution with a fellow Yale alumnus, Andy Lipka. Guests have included Stephen Breyer,[22] Bob Woodward,[23] Kate Shaw,[24] Linda Greenhouse,[25] and Gary Hart.[26]

Remove ads

Personal life

Amar and his wife, Vinita Parkash, married in 1989.[citation needed] He is politically a pro-choice Democrat.[27]

Selected works

Books

- The Constitution and Criminal Procedure: First Principles (1997) ISBN 0-300-06678-3

- For the People (with Alan Hirsch) (1997) ISBN 0-684-87102-5

- The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction (1998) ISBN 0-300-07379-8

- Processes of Constitutional Decisionmaking (ed. with Paul Brest, Sanford Levinson, and Jack M. Balkin), (2000) ISBN 0-7355-5062-X

- America's Constitution: A Biography (2005) ISBN 1-4000-6262-4

- America's Unwritten Constitution: The Precedents and Principles We Live By (2012) ISBN 978-0-465-02957-0

- The Bill of Rights Primer: A Citizen's Guidebook to the American Bill of Rights (with Les Adams) (2013) ISBN 978-1-62087-572-8

- The Law of the Land: A Grand Tour of Our Constitutional Republic (2015) ISBN 978-0-465-06590-5

- The Constitution Today: Timeless Lessons for the Issues of Our Era (2016) ISBN 978-0-465-09633-6

- The Words that Made Us: America's Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840 (2021) ISBN 978-0-465-09635-0

- Born Equal: Remaking America's Constitution, 1840-1920 (2025) ISBN 978-1-541-60519-0

Articles

- Amar, Akhil Reed (1985). "A Neo-Federalist View of Article III: Separating the Two Tiers of Federal Jurisdiction". Boston University Law Review. 65 (2): 205–272.

- — (1987). "Of Sovereignty and Federalism". Yale Law Journal. 96 (7): 1425–1520. doi:10.2307/796493.

- — (1988). "Philadelphia Revisited: Amending the Constitution Outside Article V". University of Chicago Law Review. 55 (4): 1043–1104. doi:10.2307/1599782.

- — (1989). "Marbury, Section 13, and the Original Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court". University of Chicago Law Review. 56 (2): 443–99. doi:10.2307/1599844.

- — (1991). "The Bill of Rights As a Constitution". Yale Law Journal. 100 (5): 1131–1210. doi:10.2307/796690.

- — (1992). "Child Abuse As Slavery: A Thirteenth Amendment Response to DeShaney". Harvard Law Review. 105 (6): 1359–85.

- — (1992). "The Case of the Missing Amendments: R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul". Harvard Law Review. 106 (1): 124–61.

- — (1992). "The Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment". Yale Law Journal. 101 (6): 1193–1284. doi:10.2307/796923.

- — (1994). "The Consent of the Governed: Constitutional Amendment Outside Article V". Columbia Law Review. 94 (2): 457–508. doi:10.2307/1123201.

- — (1994). "Fourth Amendment First Principles". Harvard Law Review. 107 (4): 757–819. doi:10.2307/1341994.

- —; Lettow, Renée B. (1995). "Fifth Amendment First Principles: The Self-Incrimination Clause". Michigan Law Review. 93 (5): 1193–1284.

- — (1995). "Foreword: Sixth Amendment First Principles". Georgetown Law Journal. 84: 641–712.

- — (1999). "Intratextualism". Harvard Law Review. 112 (4): 747–827. doi:10.2307/1342297.

- — (2000). "The Supreme Court, 1999 Term; Foreword: The Document and the Doctrine" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 114 (1): 26–134.

- — (2009). "Bush, Gore, Florida, and the Constitution" (PDF). Florida Law Review. 61 (5): 945–68.

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads