Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

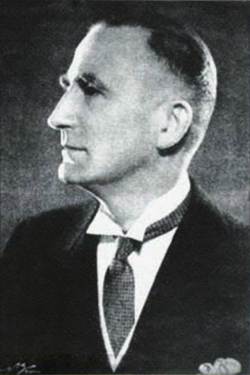

Andriy Melnyk (officer)

Ukrainian military officer and politician (1890–1964) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Andriy Atanasovych Melnyk[a] (Ukrainian: Андрій Атанасович Мельник; 12 December 1890 – 1 November 1964) was a Ukrainian military and political leader best known for leading the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists from 1938 onwards and later the Melnykites (OUN-M) following a split with the more radical Banderite faction (OUN-B) in 1940.

A veteran of the First World War and a senior officer in the army of the Ukrainian People's Republic during the Ukrainian War of Independence, Melnyk went on to cofound the Ukrainian Military Organisation in 1920 that continued the armed struggle against Poland in Western Ukraine and which later formed the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in 1929.

Melnyk was selected to lead the OUN in 1938 after the assassination of Yevhen Konovalets by the NKVD and directed the OUN-M to collaborate with Nazi Germany during the Second World War on the Eastern Front. However, Melnyk was placed under house arrest in Berlin from mid-1941, though he would continue to advocate for collaboration, and later transported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp in July 1944.

He was released in October and taken to Berlin in order to negotiate support for the retreating German Army, assuming a leading role in brokering a common stance between a broad spectrum of Ukrainian nationalist groups represented under the Ukrainian National Committee. However, with the war nearing its end and Nazi officials still rejecting demands for the recognition of an independent Ukrainian state, Melnyk and his supporters withdrew from the committee and travelled west in early 1945 to meet the Allied advance.

Melnyk continued to lead the OUN-M in exile until his death in 1964.

Remove ads

Early life and education

Andriy Atanasovych Melnyk was born in Volya Yakubov, a village near Drohobych, Galicia, to Maria Kovaliv (d.1894/7) and Atanas Melnyk (d.1905), a public figure who at a relatively young age became village head and set up a local branch of the Prosvita society.[1][2] Melnyk graduated from a gymnasium in Stryi in 1910.[3]

Both his parents died prematurely of tuberculosis, leaving him to be raised by his remarried father's widow, Pavlyna Matchak, who paid for two surgeries relating to his own struggle with the disease between 1910 and 1912, removing two ribs.[2][1] Between 1912 and 1914 he studied forestry at the Higher School of Agriculture in Vienna, though his studies were interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War.[2][4]

Remove ads

First World War (1914-1917)

Summarize

Perspective

In 1914, Melnyk volunteered in the newly formed Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (USS) where he commanded a company that was engaged in sabotage, rising from a khorunzhyi to the rank of lieutenant.[5][6] He later fought in the Battle of Makivka [ru] and received the silver Signum Laudis medal in late 1915 during an awards ceremony by Archduke Karl.[7][b]

He was reportedly referred to as "Lord Melnyk" by his fellow Ukrainian and Austrian officers who felt that he embodied the English concept of a gentleman, which at that time had been an ideal in Central Europe.[9] In early September 1916, Melnyk was wounded and taken prisoner by the Russians during the Battle on Mount Lysonia [ru] alongside several hundred USS soldiers.[10][11]

Captivity

Melnyk and his comrades in the USS (including Roman Sushko and Fedir Chernyk [ukr]) were transferred between several prisoner-of-war camps, including briefly one in Tsaritsyn, before they were moved to a lightly guarded internment camp in the village of Dubovka as of March 1917.[2][12][13][c] Melnyk became a close associate of Yevhen Konovalets, a Ukrainian second lieutenant captured in 1915 who was held in the Tsaritsyn camp and from whom Melnyk learned of the developments in Ukraine surrounding the February Revolution and the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II.[2]

The Central Rada was initially reluctant to form a regular army and, out of fear of being accused of Austrophilism, refused to accept former members of the Austro-Hungarian army from Galicia into the first Ukrainised regiments.[15]

Melnyk worked with his fellow USS officers in the internment camp to organise a system of lecture courses for their fellow prisoners-of-war on political economy, the history and geography of Ukraine, and military affairs in preparation for joining the Ukrainian War of Independence.[16][15] Historian Yuriy Shapoval notes a reported account of a conversation Melnyk had with a Russian general who asserted his belief in the existence of the All-Russian people to which Melnyk responded that the name Rus' had been appropriated by Peter the Great.[2] Former Austrian soldiers were later permitted into Ukrainian ranks and Konovalets, who was working to organise a military unit,[d] sent word to the Dubovka camp whereafter Melnyk and his fellow officers made their escape in late December 1917, joining Konovalets in Kyiv in early January 1918 in the early stages of the Russian Civil War.[18][19]

Remove ads

Ukrainian War of Independence (1918-1920)

Summarize

Perspective

On arriving in Kyiv, Melnyk assumed the position of chief of staff in the Galician-Bukovinian Kurin of the Sich Riflemen, commanded by Konovalets, under the Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR).[2][20] Amid a lack of coordination among nationalist forces, Konovalets and Melnyk developed an operation plan to quell the 1918 Kyiv Arsenal January Uprising in which the Sich Riflemen distinguished themselves and played a key role in liberating the city.[21][2] Melnyk held the position of otaman in the Ukrainian People's Army (UNA) and in recognition of his contribution was conferred the rank of major as of March and later the rank of colonel.[22] Kyiv was captured in February by the Bolsheviks, themselves dislocated by the German army in March following the collapse of the frontlines and aided by the Sich Riflemen per the Bread Peace.

Dissatisfied with disruption caused by the socialist agrarian reforms of the Central Rada, the German military authorities supported a coup d'état in April and installed the Ukrainian State in its place.[23] Melnyk accompanied Konovalets to a meeting with Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi on 29 April, with the Sich Riflemen forced to disband on 1 May after refusing to recognise Skoropadskyi's authority.[24] Alongside Konovalets and other senior officers, Melnyk met with Skoropadskyi in late July and was part of a delegation on 31 August that swore an oath of allegiance to the Hetman in return for the reinstatement of the Sich Riflemen.[25][26] He subsequently participated in the formation of a new Sich Riflemen unit in Bila Tserkva under the authority of the Hetman.[2]

Melnyk and Fedir Chernyk travelled to Kyiv on 30 October to meet with representatives of the socialist Ukrainian National Union, including Volodymyr Vynnychenko and Yuriy Tyutyunnyk, for preliminary discussions about an uprising against the Hetmanate.[27][28] The Sich Riflemen subsequently supported Symon Petliura's Directorate in the November 1918 Anti-Hetman Uprising, incited by a proposed federal union with White Russia.[2] With the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that same month, the Polish-Ukrainian War simultaneously broke out for control of Western Ukraine. Hetman Skoropadskyi was successfully ousted and the UPR re-established in Kyiv in December.[2] Amid the intensification of anti-Jewish pogroms in January 1919, Melnyk, briefly acting as commander of the Siege Corps,[e] issued an order to court-martial and administer the "most severe punishment" to anyone caught agitating for or spreading rumours about the possibility of pogroms.[31][f] Historians generally agree that such orders typically achieved little in the way of restoring discipline among Petliura's forces.[32] Melnyk attended a conference in Kyiv on 16 January as a representative of the Rifle Council,[g] alongside other pro-independence parties.[34] At the conference, the Riflemen put forward a proposal to reform the government into a temporary triumvirate military dictatorship consisting of Petliura, Konovalets, and Melnyk on the basis that it would enable them to better meet the demands of the state-building process, though this was rejected by the other parties present including Petliura and the Directorate.[34] Melnyk assumed the position of chief of staff of the wider UNA from March to June and assistant commandant of the Sich Riflemen from July to August.[2]

Following the fall of Kyiv and amid a bleak strategic position, the regular army was dissolved in December 1919 upon the switch to partisan warfare.[36][37] That month, Melnyk fell ill from a typhus epidemic; soon after he was captured by Polish troops at a train station and taken to a hospital in Rivne.[38][2] He recovered and was released in January 1920 during negotiations pertaining to the Treaty of Warsaw that would in April cede most of Western Ukraine to Poland in return for an alliance and Polish recognition of the UPR.[38] Travelling from Warsaw in February, Melnyk delivered funds to improve the living conditions of Sich Riflemen who were interned by the Poles in Rivne and Lutsk.[39] In March, Melnyk was appointed military attaché of the UNA in Czechoslovakia, based in Prague, intending to assist Konovalets in setting up a new unit to aid the Kyiv offensive from ZUNR soldiers interned in Jablonné v Podještědí and Ukrainian prisoners-of-war in Europe.[40] However this failed to materialise due to discontent among West Ukrainians and members of the Ukrainian Galician Army and became irrelevant with the subsequent collapse of the Polish-Ukrainian lines.[41]

Following a Red Army counteroffensive and the Battle of Warsaw in August, the polyfactional conflict culminated in the 1921 Peace of Riga that partitioned Ukrainian territory, placing much of Ukraine in the hands of the Bolsheviks, who would go on to effectively repress Ukrainian nationalist and cultural movements, and the west under Polish control, with Transcarpathia and Bukovina annexed by Czechoslovakia and Romania respectively.[42][43][44]

Remove ads

Interwar political activities (1920-1938)

Summarize

Perspective

Alongside Konovalets and former Sich Riflemen in August 1920, Melnyk was a founding member of the Ukrainian Military Organisation (UVO), an underground militant group that continued the armed struggle against Poland and engaged in acts of terrorism and assassinations.[2] Having completed his forestry studies in Prague and Vienna, Melnyk moved to Lviv in September 1922, upon which he was briefly arrested, and assumed the position of head of the UVO Home Command in 1923.[43][2][45] In April 1924, Melnyk was arrested in connection to the Olha Basarab case and imprisoned in Lviv for intelligence activities against the Polish state.[2][46][47]

Following his release from prison in September 1928, Melnyk largely stepped back from direct involvement in the UVO underground and married Sofiya Fedak in February 1929. Sofiya was the daughter of lawyer Stepan Fedak, one of the wealthiest men in Galicia, whose sister had married Konovalets and whose brother had attempted to assassinate Polish Chief of State Marshal Piłsudski in 1921.[8][48][49] Earlier that month the UVO had merged with several far-right nationalist student movements to form the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) with Yevhen Konovalets at its head.[50][4] Melnyk turned down an offer by Konovalets to head the OUN Home Command; instead in the early 1930s Melnyk chaired the National Senate, a collegiate body that coordinated the activities of the Home Command and the UVO.[i][51] During this time, Melnyk worked on the large estates of the Catholic Metropolitanate of Galicia, headed by Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky.[52][2][4] From 1933 onwards, he served as chairman of Orly ('Eagles'), a Galician Catholic youth organisation that was considered to be anti-nationalist by much of the OUN youth in the area.[53][48]

Remove ads

Leader of the OUN (1938-1940)

Summarize

Perspective

On hearing of Konovalets's assassination by the NKVD outside a Rotterdam cafe in May 1938, Melnyk and his wife travelled to Vienna though due to a delay in conveying the news they were unable to reach Rotterdam in time for the funeral five days later and instead travelled from Vienna to Rome to meet Konovalets's widow (Melnyk's sister-in-law).[54] On returning to Lviv in June, Melnyk learned that the Leadership of Ukrainian Nationalists (the OUN's executive command in exile and hereon the PUN or the Provid) could not agree on a leader from amongst themselves and were considering asking Melnyk to become leader of the OUN.[54][55]

Melnyk travelled to the Free City of Danzig where he met in September with Provid member Omelian Senyk who informed him that Konovalets's oral will stated him as his preferred successor[j] whereafter he accompanied Senyk to Vienna and was elected head of the PUN on 14 October.[56][57] He was chosen by the Provid in part because of the hope for more moderate and pragmatic leadership and due to a desire to repair strained ties with the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.[53] Andrey Sheptytsky had sharply denounced the OUN for inciting acts of violence against Ukrainians that disapproved of its methods and its radical nationalism and had charged the organisation with morally corrupting the youth.[58]

Support for Carpatho-Ukraine

Melnyk took over the leadership in the midst of the Sudetenland Crisis and the OUN's opportunistic support of Carpatho-Ukraine with the organisation initially directing, in his own words, "all [their] forces and means at [their] disposal" to aid them.[59] Melnyk despatched Oleh Olzhych to Transcarpathia to represent the PUN, as well as sending others on diplomatic missions, while as many as 2,000 young radicals from Galicia crossed the border.[60] Melnyk later refined the OUN's support to cultural figures and experienced military specialists on the request of Carpatho-Ukrainian leader Avgustyn Voloshyn who had become aware that a number of nationalists, some of whom he derided in his correspondence as "revolutionary shouters", were planning a coup d'état.[61]

Following on from the November 1938 First Vienna Award, itself part of the broader partition of Czechoslovakia, the autonomous region declared its independence from the Second Czechoslovak Republic in March 1939, though Nazi Germany failed to respond to appeals for recognition and the short-lived state was thus invaded and annexed by the Kingdom of Hungary a day later.[62] In the aftermath of this defeat Melnyk privately announced his intention to resign as head of the PUN, officially going on leave until a congress was convened to select a new leader. However he later withdrew his resignation, likely yielding to intense persuasion according to historian Roman Wysocki.[63]

Melnyk was present in Venice in July for the formalisation of cooperation and recognition between the OUN and the government of Carpathian Ukraine, with the events of the past months dealing an initial blow to Ukrainian nationalists' hopes that Hitler's Germany would support their ambitions in the event of an anticipated conflict against the USSR, compounded by the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact a month later.[64][65][62] According to historian Myroslav Shkandrij, the younger generation within the OUN felt that the PUN had failed to provide Carpatho-Ukraine with the necessary support and had overrelied on support from Germany.[66]

Formal ratification as leader

At the Second Great Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists in Rome on 27 August 1939, Melnyk was formally ratified as leader of the OUN and reaffirmed its ideology[k] as continuing in the vein of natsiokratiia[l] (literally translating to 'natiocracy'), which has been characterised by scholars as a Ukrainian form of fascism[69][70] and[71]/or integral nationalism,[72][73] itself sometimes characterised as proto-fascist,[74] or more broadly as extreme or radical nationalism influenced by fascist movements.[75] At the conference, Melnyk was styled under the title vozhd in the Führerprinzip tradition.[76][77][78] In a May 1939 letter to German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, Melnyk had claimed that the OUN was "ideologically akin to similar movements in Europe, especially to National Socialism in Germany and Fascism in Italy".[77][79]

Melnyk and his supporters within the OUN were generally more conservative and less inclined towards the radical anti-clericalism and terror that had characterised the organisation prior, highly regarding the ideology of Vyacheslav Lypynsky while often distancing themselves from Dmytro Dontsov's ideology in public.[80][81] The elevation of Melnyk to the position of leader exacerbated a generational divide within the organisation between an older, more cautious generation, many of whom had fought in the conflicts surrounding the First World War, and a younger, more bellicose generation heavily inspired by the works of Dontsov that demanded a more charismatic and radical leader and which had begun to coalesce around Stepan Bandera.[82][83] Bandera had attained notoriety following his role in the assassination of Polish Interior Minister Bronisław Pieracki and the publicity that arose from the 1935 Warsaw and 1936 Lviv trials.[84]

According to John Alexander Armstrong, Melnyk "refused to raise the nation to the level of the absolute" which was likely taken as sign of weakness by much of the more radicalised younger generation.[85] Armstrong posits that taken together with his association with the Church and his calm and dignified disposition that had little resonance among these members, this made Melnyk incapable of managing the generational divide that had been up until then skillfully and largely successfully managed by Konovalets.[85]

Collaboration with Nazi intelligence

From 1938 onwards, Melnyk was recruited into the Abwehr for espionage, counter-espionage and sabotage, a relationship that had its roots as far back as 1923 pertaining to the UVO, in return for providing the organisation with financial support. The Abwehr's goal was to run diversion activities after Germany's planned attacks on Poland and the Soviet Union whereby Melnyk assisted in planning the largely aborted OUN Uprising of 1939 and was assigned the codename 'Consul I'.[86][87] Following the Nazi–Soviet Pact, Melnyk met with the head of the Eastern Department of the German Foreign Office in Berlin on 3 September 1939 where he was told that Ukrainian armed involvement against Poland neither lay in German nor Ukrainian interests and to reserve his forces.[88]

Wilhelm Canaris later gave the order to ready the OUN group on 11 September and met with Melnyk in Vienna where he directed him to oversee the drafting of a constitution for a west Ukrainian state. Canaris congratulated Melnyk on "the successful resolution of the question of western Ukraine" and asked for a list of government officials.[89][90] Melnyk instructed Roman Sushko, who was to lead an expedition into Poland, to follow the doctrine of 'building a state from the first village' and transmitted broadcasts from a military radio station in Vienna calling on Ukrainians not to resist the Wehrmacht and to welcome them as liberators.[m][92][89][93]

Sushko's legion was activated on 12 September and, in mid-September, Melnyk joined OUN members at Sambir from where they intended to move their nascent headquarters to Lviv at the earliest opportunity.[89][94] However, OUN members retreated westwards with the German Army after the USSR commenced their invasion on 17 September.[95] The draft constitution was completed in 1940 by Mykola Stsiborskyi, the OUN's chief theorist and organisational officer,[n] and encompassed the establishment of a totalitarian state under a Vozhd (to be Col. Melnyk) with the Ukrainian-Jewish population singled out for distinct and ambiguous citizenship laws.[90]

Remove ads

Split with Bandera and the OUN(m) (1940-1941)

Summarize

Perspective

In January 1940, and following his release from prison during the Nazi-Soviet partition of Poland that unified Ukrainian lands under the Soviet Union, Bandera travelled to Rome to present Melnyk with a series of demands, among them the replacement of certain members of the Provid with members of the younger generation[o] though this was rejected by Melnyk. Bandera subsequently made a challenge to the PUN on 10 February by establishing a 'revolutionary' Provid in Nazi-occupied Kraków, turning down Melnyk's offer to allow him an advisory position in the PUN.[96][97][98]

On 5 April, Melnyk and Bandera met in Rome in a final unsuccessful attempt to resolve the growing divide between the two emerging factions with Melnyk declaring the Revolutionary Leadership illegal on 7 April and appealing on 8 April to OUN members not to join the 'saboteurs'.[97][99] Melnyk decided to put the members of the Revolutionary Leadership before the OUN tribunal, in response to which Bandera and Stetsko rejected Melnyk's leadership and responded in kind.[98][100] The OUN subsequently fractured into two rival organisations: the Melnykites (Melnykivtsi or the OUN-M) and the Banderites (Banderivtsi or the OUN-B) while the tribunal officially removed Bandera from the OUN (effectively now the OUN-M) on 27 September.[4][101]

Avgustyn Voloshyn praised Melnyk for having an ideology based in Christianity and for not placing the nation above God while auxiliary bishop of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Lviv Ivan Buchko declared that nationalists possessed an outstanding leader in Melnyk.[102] In July 1940 Melnyk travelled from Italy to Germany intending to return, with his base being in Rome, but his requests for a visa were denied— historian Yuriy Shapoval asserts the view that this was on the initiative of the German authorities.[2][103] From 1940 onwards, Melnyk and his wife lived in a Berlin apartment near Kurfürstendamm, rented from the German general Hermann Niehoff.[104]

In April 1941, the Banderite faction held a Second Great Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists in Nazi-occupied Kraków where Bandera was proclaimed providnyk of the OUN (technically the OUN-B), having declared the original 1939 Second Great Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists that had officially ratified Melnyk as leader to have been arear of internal laws.[57] Though Melnyk received widespread support among Ukrainian émigrés abroad, Bandera's position on the ground in Western Ukraine and the demographics of his base meant that he gained control of the vast majority of the local apparatus in the region.[105] Effective Soviet repression in Central and Eastern Ukraine meant that most of the Ukrainians living in these regions were unaware of the split in the OUN, benefitting the more active Banderites in their battle for legitimacy.[106] In late June and July Melnyk made several conciliatory overtures to the Banderites, calling for unity and signalling that their views would be heard at a Third Great Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists if they came back into the fold.[107]

Remove ads

Second World War and collaboration with the Nazis (1941-1945)

Summarize

Perspective

Working from their bases in Berlin and Kraków, both factions of the OUN formed marching groups and planned to follow the Wehrmacht into Ukraine during the June 1941 German invasion of the Soviet Union in order to recruit supporters and set up local governments.[110] As soon as the collaborationalist Nachtigall Battalion entered Lviv on June 30, the group of Banderites, directed by Bandera from Kraków, proclaimed an independent Ukrainian state, though the German military authorities caught wind of this and cracked down upon the OUN-B. Bandera was arrested on the eve of the proclamation and the crackdown on the OUN-B was later expanded after the assassination of two Melnykite Provid members in Zhytomyr in August.[111][112] On 6 July, Melnyk and his fellow former officers of the UNA submitted an appeal addressed to Adolf Hitler through the Abwehr that reads thus:

"The Ukrainian people, whose century-old struggle for freedom has scarcely been matched by any other people, espouses from the depths of its soul the ideals of the New Europe. The entire Ukrainian people yearns to take part in the realisation of these ideals. We, old fighters for freedom in 1918-1921, request that we, together with our Ukrainian youth, be permitted the honour of taking part in the crusade against Bolshevik barbarism. In twenty-one years of a defensive struggle, we have suffered bloody sacrifices, and we suffer especially at present through the frightful slaughter of so many of our compatriots. We request that we be allowed to march shoulder to shoulder with the legions of Europe and with our liberator, the German Wehrmacht, and therefore we ask to be permitted to create a Ukrainian military formation."[113]

Detention in Berlin

Having travelled several times between Berlin and Kraków to oversee preparations for the OUN-M expeditions, Melnyk had his movements restricted to Berlin in late July under house arrest and Gestapo surveillance.[104][114][4] On 28 July, Melnyk sent a letter to Heinrich Himmler protesting the annexation of Galicia into the territory of the General Government.[114] The OUN-M formed the Bukovinian Battalion under the Abewehr in August which, alongside OUN-M members in the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, would go on to be implicated in the implementation of the Holocaust— Melnyk's own reaction and proximity to this is underesearched in the scholarship.[115][116][117][118] In contrast to the OUN-B, Melnyk and his supporters meanwhile avoided making any unilateral proclamations, competing with Bandera's supporters for influence in Western Ukraine and intent on cooperating and gaining favour with the SS and the Wehrmacht in pursuit of a military-political arrangement similar to that of Tiso's Slovakia and Ustaša Croatia.[2][119][120][q] In response to the assassination of Mykola Stsiborskyi and Omelian Senyk in August, Melnyk refused to countenance violent reprisals against the Banderites.[121]

The OUN-M based its Ukrainian headquarters in Kyiv with the founding of the Ukrainian National Council (UNRada) on 5 October, styled off of its namesake under the West Ukrainian People's Republic and intended to serve as the basis for a future Ukrainian state.[122][123] Initially, Melnyk's supporters enjoyed support against the Banderites from the German military authorities, with some Melnykites informing on OUN-B members.[112] However, alarmed at the OUN-M's growing strength in Eastern and Central Ukraine and taken together with the incompatibility of Ukrainian statehood with Nazi designs on the region, the SS and government officials overruled the Wehrmacht and ordered a crackdown on the organisation with the UNRada dissolved in November 1941, the Melnykite newspaper Ukrainian Word puppeted in December, and many OUN-M members arrested or executed by the SD from November onwards.[124][120][r] From Berlin, Melnyk sent letters to Nazi officials protesting the change in policy and attempted to secure the release of arrested and persecuted members, periodically receiving information of further crackdowns upon OUN-M members in Ukraine.[s][104]

Melnyk declared in a 1 January 1942 pamphlet:

"In the German soldiers, we see those who, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, drove the Bolsheviks out of Ukraine; we are obliged to consciously and organisedly assist them in the crusade against Moscow, regardless of any difficulties... We are living at the time of the birth of a new order in Europe. In a Europe that is renewed and consolidated under the leadership of National Socialist Germany, Ukraine must take its place side-by-side with other nations. It is tasked with responsibilities dictated by its geopolitical position and its historical traditions."[120]

With their letters going unanswered, the OUN-M leadership resolved to write an appeal to Adolf Hitler in December 1941 'on behalf of all Ukrainians' in which they expressed dissatisfaction at the state of German-Ukrainian cooperation, framing their criticisms of German policy as being intended to notify Hitler "about the real state of affairs in Ukraine".[120] The memorandum was sent on 14 January 1942, bearing the signatures of Melnyk, chairman of the dissolved UNRada Mykola Velychkivsky, Catholic Metropolitan of Galicia and Archbishop of Lviv Andrey Sheptytsky, President of the UPR in exile Andriy Livytskyi, and chairman of the UNA émigré veterans' General Council of Combatants Mykhailo Omelianovych-Pavlenko.[120][125] In a letter to Sheptytsky dated 7 July 1942, Melnyk wrote:

"As always before, I am now ready to meet as far as possible in carrying out the initiatives of Your Excellency to eliminate disagreements within our people, which especially at this time needs the greatest possible unity to achieve the ideal of the Nation under the single current political factor in Ukraine— the OUN...

In my experience so far, when I have given so much evidence of my best will and understanding for both human weaknesses and ambitions, and for the peculiar situations and demands of the wave, including the disposition of my own person, I have an unshakable conviction of the right path: not to indulge the disaster, but to fight the disaster. My only regret is that all our citizens did not follow this path at once."[126]

On being relayed the decisions of the May 1942 Pochaiv Conference that began to chart an independent course away from cooperation with Germany, Melnyk assessed the decisions as being those that "went in a direction that the Organisation had not yet defined or formulated".[127] Melnyk continued to lobby German officials for the creation of an armed Ukrainian unit and the prospect for recognition of a Ukrainian state, sending a lengthy memorandum to Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel on 6 February 1943 arguing that Ukrainians would do everything in their power to fight the Bolsheviks if they thought it would lead to statehood.[t][128] According to Timothy Snyder, where the OUN-B perceived an "urgent need for independent action" in response to the German defeat at Stalingrad, the OUN-M saw an opportunity for more productive collaboration with the Germans.[129]

Melnyk maintained semi-official contacts with OUN-M activists in Ukraine, intermittently being able to despatch directives, though his proximity to decision-making on the ground in the context of the Galicia-Volhynian massacres of Polish civilians, principally perpetrated by the UPA while the OUN-M was practically marginalised, and pertaining to the Ukrainian Legion of Self-Defense is less clear.[104] Historian Yuri Radchenko asserts that "the PUN did not have clear centralised control over its rank-and-file members" with the OUN-M being "fairly decentralised" during the war.[120] According to Snyder, the OUN-M were "in principle committed to the same ideas" as the OUN-B with regards to an ethnically homogenous state while historian Yuriy Shapoval cites Polish intelligence sources from 1927 to 1934 that characterise Melnyk as holding hostile views towards Poles.[130][2] However, Snyder also asserts that the OUN-M didn't see the massacres as feasible nor desirable while historians Yuri Radchenko and Andrii Usach note that individual Melnykite activists opposed the ethnic cleansing of Poles, suggesting that this may have been concentrated around Melnyk's second-in-command Oleh Olzhych.[130][131]

Imprisonment

In late 1943, and amid Allied bombing raids, Melnyk moved with his wife to Vienna in an attempt to restore contact with OUN-M members in occupied Ukraine, though, following a brief trip to Berlin where he likely tried to re-establish connections with Nazi officials, he and his wife were arrested by the Vienna Gestapo in late January 1944 and taken back to the capital.[104] The following day, Melnyk was moved to a dacha in Wannsee where he was frequently interrogated by Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller and SS-Hauptsturmführer Wilhelm Wirsing [ukr].[104] Melnyk was permitted to meet OUN-M member Yevhen Onatsky, a representative of the OUN in Italy and one of its ideologists,[u] at a dinner where they were joined by Gestapo agents and obligated to speak German.[104][132][133] Melnyk was subsequently moved on the turn of March to the alpine settlement of Hirschegg where he was held as a Sonderhaftling (special prisoner) at the Ifen Hotel.[104] Fellow political prisoner and former French ambassador to Germany André François-Poncet, with whom he would attend the local church service on Sundays,[104] wrote of him in his diary:

[Friday 3rd March] "This Melnyk is intelligent, distinguished, very polite, with very good manners; his wife, a small brunette, with lively eyes, delicate facial features, and uses a lorgnette. Both seem indignant at the deprivation of freedom they must endure. They might become pleasant companions in suffering."[2][134]

François-Poncet stated in an interview following Melnyk's death:

"The late Colonel was always sad and taciturn. When we met him in the morning, he radiated great dignity and gentlemanliness. He was the first to greet everyone with a smile and always asked about my health. And he never talked about himself... However, I remember that there were moments when the late Colonel Melnyk came out of his reserve and became talkative. This happened when he remembered the liberation struggle of Ukraine."[2][135]

In July 1944, Melnyk was moved first to Berlin where on 23 July he was accused of holding political conversations with fellow arrested persons and trying to establish contact with the OUN-M in occupied-Ukraine.[104] On trying to establish contact with OUN-M members in Ukraine, Melnyk was charged on two counts: attempting to obtain information about occupied-Ukraine from Ukrainian Ostarbeiter and refusing to sign a statement-declaration saying that he would stop attempting to establish contact with OUN-M members.[104] Subsequently he and his wife were taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp where they were held in a fenced house that had a housekeeper.[104] Melnyk was later moved on 4 September to a Zellenbau isolation cell, near where Bandera was also being held and from whom he learned of the death of Oleh Olzhych, the acting head of the OUN-M, through the passing of clandestine notes.[104]

Release from Sachsenhausen and the Ukrainian National Committee

In autumn 1944, Ukrainian nationalist political leaders were taken to Berlin to negotiate support for the retreating German Army, who at this point were suffering from manpower shortages, whereby they sought political concessions pertaining to Ukrainian independence under the auspices of the Ukrainian National Committee (UNC).[62][104] Melnyk was released on 18 October alongside a number of OUN-M members and taken to Hotel Esplanade in Berlin.[104] Having failed to locate Bandera's proposed candidate for negotiations, SS-Obersturmbannführer Fritz Arlt turned to Melnyk who was successful in negotiating a common stance among Ukrainian nationalists, including the monarchist Hetmanites under Pavlo Skoropadskyi, the socialist Petliurites under Mykola Livytskyi, and the OUN-B under Bandera.[136][137]

In response to a proclamation by Andrey Vlasov's Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (KONR) claiming to represent all peoples of the Soviet Union, Melnyk signed a petition prepared by ten non-Russian national political groups on behalf of Ukrainian nationalists, appealing to Alfred Rosenberg who subsequently sent a protest to Adolf Hitler concerning Vlasov's committee.[138] In concert with the UNC, Melnyk prepared a declaration pledging the establishment of a Ukrainian state, calling for no subordination to Vlasov's KONR, and demanding that the SS Galicia Division form the basis of a Ukrainian army, while also preparing concessions that would have seen Galicia remain in the German sphere of influence.[137] Though Nazi officials nominally granted the demand for a Ukrainian National Army, the nationalists' demand for statehood was rejected.[139][137] Historian Paweł Markiewicz posits that Ukrainian nationalists engaged with this process in spite of Nazi Germany's bleak strategic position in late 1944 in the hopes of strengthening their émigré bases with there being over two million Ukrainians under German control at the time, including over a million Ostarbeiter.[140]

Dissatisfied with the progress and value of these negotiations, Melnyk and his supporters withdrew from the committee and instead organised a meeting in Berlin in January 1945 whereupon it was decided that OUN-M members would meet the Allied advance and seek to familiarise the Western Allies with the Ukrainian independence movement.[114] Melnyk left for Bad Kissingen in February, with the town occupied by American troops on 7 April whereafter Melnyk sent congratulatory telegrams to President Harry S. Truman, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill.[137][114] According to the Cultural Department of the OUN-M[v] (founded by Olzhych) and its archives, a group of senior Melnykites, in coordination with Melnyk, submitted a memorandum to the U.S. military administration whereby it was understood that displaced Ukrainians were to be afforded the right to be separated from Poles and Russians and allowed to display the blue-and-yellow flag, which was later the case and general policy for displaced persons.[w][141][142][143]

Remove ads

Post-WWII exile

Summarize

Perspective

After the war, Melnyk remained in the West and lived with his wife in Clervaux, Luxembourg, having become acquainted with Prince Félix when he was working on the estates of the Lviv Metropol, as well as later living in West Germany and Canada.[2]

Melnyk remained politically active and continued to lead the now-exiled OUN-M, authoring several historical articles on the Ukrainian independence movement, and was instrumental in the founding of the Ukrainian Coordinating Committee in 1946.[4] At the Third Great Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists in 1947, Melnyk was elected head of the OUN-M for life.[144] Joined in the effort by President of the UPR in exile Andriy Livytskyi, Melnyk played an instrumental role in reconstituting the Ukrainian National Rada in July 1948 which thereon served as the legislative body of the UPR in exile and sought to unify Ukrainian émigré organisations in Europe for further consolidation with the Pan-American Ukrainian Conference that had been formed in November 1947. However, the Union of Hetman Statesmen objected to the associations with the UPR and the OUN-B left in 1950 after demanding a more central role.[145][146] In 1954, Melnyk contributed a collection of eulogies of OUN and OUN-M members to a book marking the 25th anniversary of the creation of the OUN.[147][148]

Following an address to the Ukrainian National Federation of Canada in May 1957, Melnyk began to actively lobby the Ukrainian diaspora for the establishment of a pan-Ukrainian umbrella organisation capable of accommodating the fragmented landscape of diaspora organisations.[149][4] On 6 April 1958, Melnyk delivered a speech at the IX Congress of the Ukrainian National Alliance in France (UNE) in Paris that was also published in Ukrainian Word (Paris, est. 1948) commemorating the 40th anniversary of the declaration of Ukrainian independence and rallying readers and listeners to contribute to the founding of a "World Ukrainian Congress".[150] The OUN-M withdrew from the UNRada in October 1957, rejoining in 1961.[151]

Leaders of the OUN-M and OUN-B, including Melnyk, Bandera, Yaroslav Stetsko, Mykola Kapustiansky, and Dmytro Andriievsky (OUN-M) attended a ceremony at Konovalets's grave in Rotterdam on 23 May 1958 to mark the 20th anniversary of his assassination.[152]

Remove ads

Death

Summarize

Perspective

Melnyk died in Cologne, West Germany, on 1 November 1964 at the age of 73, and was buried at Bonnevoie cemetery, Luxembourg.[4] Melnyk's aspiration of consolidating the diaspora was finally realised in 1967 with the founding of the World Congress of Free Ukrainians.[153][4]

Commemoration

In July 2006, a monument to Melnyk was unveiled in his native village of Volya Yakubov in Drohobych Raion.[154] In late 2006, and as a result of a meeting between modern OUN-M[x] leader Mykola Plaviuk and administration officials, Lviv City Council announced plans to transfer the tombs of Andriy Melnyk, Yevhen Konovalets, Stepan Bandera and other key leaders of the OUN and UPA to a new area of Lychakiv Cemetery specifically dedicated to the Ukrainian national liberation struggle, though this was not implemented.[155][156]

On the basis of the Ukrainian decommunisation laws passed by the Verkhovna Rada in 2015, Melnyk is legally recognised in Ukraine as one of the fighters for Ukrainian independence in the 20th century.[157][158]

Following a campaign by modern OUN-M activists, a second monument to Melnyk was unveiled in Ivano-Frankivsk in 2017.[159] In December 2020, the Museum-Estate of the Leader of the Ukrainian National Liberation Movement Andriy Melnyk was opened in Volya Yakubov to coincide with the 130th anniversary of his birth. The Museum-Estate is situated in a house that was owned by his relatives since his parents' house is no longer standing.[160][161]

As of 2023, Melnyk's grave was maintained by members of the Union of Ukrainian Women in Luxembourg.[162] Streets are named after him in Drohobych, Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv, Rivne, Bila Tserkva, Cherkasy, and, since 2023, Kyiv.

Views

Summarize

Perspective

Fascism

Melnyk was not an ideologue of the OUN and didn't author works in the interwar period where he set out his views.[163] The ideological-political commission of the 1939 Second Great Congress was headed by Mykola Stsiborskyi.[164] Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe surmises that Melnyk "seems also to have been an adherent to fascism", referring to Stsiborskyi, Yevhen Onatsky, and Dmytro Dontsov to whom he also applies the designation.[77]

Historian Yuri Radchenko describes Melnyk as "one of the fascist leaders or right-wing radical leaders of Europe, leaders of fascist movements," up until 1945, noting that such a designation is a matter of preference among historians.[165] Historian Marek Wojnar considers most of Melnyk's followers to instead fall into the 'radical right' classification in Stanley G. Payne's typology of authoritarian nationalist groups that divides them into fascism, radical right, and conservative authoritarian right.[166][167] In Payne's typology, the 'radical right' generally wished to destroy the existing political system of liberalism and often deliberately blurred the distinction between themselves and fascism, though were less revolutionary relative to fascists.[168]

Jews

As one of the generals of the UNA during the Ukrainian independence war, Melnyk attempted to suppress the anti-Jewish pogroms. Radchenko argues that Melnyk's views on Jews underwent a radicalisation in the interwar period, likely against the background of the Schwartzbard trial, although he notes that there are no records of him espousing an opinion on the subject. Radchenko bases this on his belief that the antisemitic propaganda of the OUN-M in the early 1940s could not have been published without Melnyk's knowledge.[169]

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- Also Andrii and Andrij

- According to historian Oleksandr Kucheruk, director of the Oleh Olzhych Library, Melnyk was also awarded an imperial sabre at this time by the Archduke.[2][8] However, historian Danylo Yanevsky notes that the rumour came from a secondary source citing unnamed witnesses and it was never confirmed by Melnyk himself.[7]

- This is further supported by historian Yuri Radchenko who states in this overview of an upcoming book chapter that is set to include a discussion on Melnyk and his views in the context of the 1941 Lviv pogroms: "Andriy Mel'nyk was against pogroms during the Revolution of 1917-1921 and was trying to stop them."

- Seated (L-R): Mykhailo Matchak, Melnyk, Konovalets, Roman Sushko, Ivan Dankiv.

Standing (L-R): Ivan Andrukh, Roman Dachkevitch, Vasyl Kuchabskyi, Yaroslav Chyzh. - The UVO persisted for a time as a separate entity under Konovalets.

- Bandera and his supporters would later claim that this was fabricated.

- A more extensive account can be found in a dedicated article on Russian Wikipedia.

- The term was coined by the OUN's chief theorist Mykola Stsiborskyi in his 1935 book by the same name that, according to historian Taras Kurylo, advocated for the organisation of a future Ukrainian state on the principles of authoritarianism, corporatism, and solidarism closely resembling those of Fascist Italy.[67] Historian Kai Struve offers the term 'ethnocracy' as a more contemporary translation.[68]

- Stsiborskyi had in 1930 written an article in the OUN's ideological journal Rosbudova natsii criticising antisemitism in Ukrainian society and arguing for the assimilation of Ukrainian Jews, though he abandoned this position in the late 1930s. According to historian Taras Kurylo he "very likely" succumbed to pressure from within the OUN.[67]

- Accounts of the remaining demands, written postwar, vary with John Alexander Armstrong treating these sources with trepidation. Historian Ivan Patryliak reports that Bandera and his entourage wanted the OUN to establish contacts with Western powers while Melnyk's objections were rooted in practical constraints. Patryliak asserts that Melnyk was concerned that the Soviet crackdown that would inevitably follow an attempted 'revolution' would severely weaken the organisation. Patryliak stresses that these discussions occurred in the context of the Nazi-Soviet pact.

- Starting points taken from the encyclopedia; paths from a map in Armstrong.

- Radchenko [trans.]: "During the German-Soviet war, the OUN (m) tried to establish cooperation with the Reich in order to create a totalitarian Ukrainian state within Hitler's "New Europe". The Melnykites had more patience than the Banderites and were ready to make concessions to the Germans. For example, they agreed to postpone the proclamation of Ukrainian independence. Supporters of Colonel Melnyk expressed their willingness to work in collaborationist bodies (police, self-government), propaganda, serve in the Wehrmacht or SS and thus "build a state from below"."

- Radchenko [trans.]: "The German Nazis viewed the territory of Ukraine as their colonial space, where there were no plans to organise any Ukrainian (even puppet) governments. The German administration (primarily the SD) feared the radicalisation of the OUN(m). SD employees and RKU bureaucrats did not rule out that the radical wing of the OUN(m) could follow the path of the OUN(b): create an anti-German underground, start propaganda against the Reich, and engage in military resistance to the Nazis."

- Historian Yuri Radchenko describes the language in Melnyk's letters as consistently restrained and diplomatic.

- The SS Galicia Division was created in May on the initiative of German governor of Galicia Otto Wächter and negotiated by Volodymyr Kubijovyč's Ukrainian Central Committee, though Melnykites played a critical role in its development and supported recruitment efforts. The Ukrainian movement to create such a unit was larger than just Melnyk.

- Onatsky had been arrested by the German police in September for having written an article after Mussolini's overthrow criticising fascism as a form of government, marking a sharp turn from his 1930 article where he enthusiastically supported Italian Fascism though criticised the Nazi conceptualisation of race and their untermensch attitudes.

- Though the Western Allies didn't officially recognise a Ukrainian nationality for fear of agitating the USSR, historian Jan-Hinnerk Antons asserts that they created purely Ukrainian DP camps due to the number of conflicts arising between Ukrainians and Poles and the fear that remaining mixed would hurt general repatriation efforts.

- Often referred to in the media without the disambiguation.

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads