Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

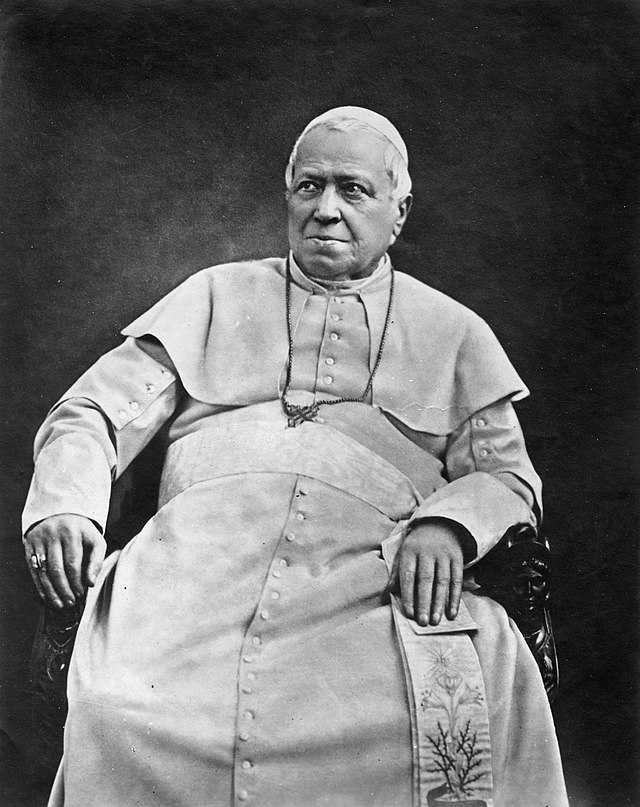

Bernard John McQuaid

American prelate From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Bernard John McQuaid (December 15, 1823 – January 18, 1909) was an American prelate of the Catholic Church. He was the first and longest-serving bishop of the Diocese of Rochester in New York State, serving from 1868 until his death. He previously served as the first president of Seton Hall University in New Jersey (1856-1868).

As a bishop, McQuaid was a leading voice of the American church's conservative wing. He publicly clashed with the liberal-minded Archbishop John Ireland and vigorously opposed Americanism.

Remove ads

Early life and education

Summarize

Perspective

Bernard McQuaid was born on December 15, 1823, in New York City to Bernard and Mary (née Maguire) McQuaid, both natives of Ireland.[1] Shortly after his birth, he moved with his parents to Paulus Hook, New Jersey (later incorporated as Jersey City), where his father worked in a glass factory operated by the brothers George and Phineas C. Dummer.[2] Bernard's mother died in 1827, when he was three years old.[2] The first Mass in Paulus Hook was celebrated in the McQuaid home in 1929.[3]

In 1832, McQuaid's father was killed by a fellow factory worker; the eight-year-old Bernard was placed in the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum in Lower Manhattan, staffed by the Sisters of Charity.[4] In 1839, McQuaid left the orphanage to prepare for the priesthood at the Mary Immaculate Juniorate, the minor seminary in Chambly, Quebec.[5] McQuaid returned to New York City in 1843, entering St. Joseph Seminary in the Bronx.[4]

As a seminarian, McQuaid suffered from a severe case of tuberculosis. Many years later, he recounted that "friends expected to put me under the sod." However, McQuaid eventually recovered and noted "I have downed them all."[6] In addition to his studies at the seminary, he served as a tutor at St. John's College in Queens, New York.[7]

Remove ads

Priesthood

Summarize

Perspective

McQuaid was ordained a priest for the Diocese of New York on January 16, 1848, by Bishop John Hughes at St. Patrick's Old Cathedral in Manhattan.[8] At that time, the Diocese of New York included Northern New Jersey. Hughes initially planned to assign McQuaid to St. Mary's Parish in Manhattan. However, Hughes's secretary, Reverend James Roosevelt Bayley, convinced Hughes that a posting outside the city would be better for McQuaid's health.[9] Hughes then named McQuaid as an assistant pastor at St. Vincent's Parish in Madison, New Jersey. Four months later, Quaid was named pastor at St. Vincent.[7]

St. Vincent's Parish in the late 1840s covered all of Morris, Sussex, and Warren Counties in New Jersey as well as parts of Union and Essex Counties.[10] McQuaid bought two horses and carriages to travel through this expansive territory. In town without Catholic churches, he celebrated masses in private homes and hotel ballrooms.[11] He erected Assumption Church, the first Catholic church in Morristown, New Jersey, in 1848 followed by St. Rose of Lima Church in Springfield, New Jersey, in 1852.[12] In 1849, McQuaid opened the first permanent Catholic parochial school in New Jersey at St. Vincent's, with another school the next year in Assumption Parish.[13] Of these two accomplishments, McQuaid later wrote,

"I feel prouder...that so many years ago I founded and established, and carried along successfully the humble parochial schools of Madison and Morristown than I ever felt at having established Seton Hall College and Seminary."[14]

In July 1853, Pope Pius IX erected the Diocese of Newark, including all of New Jersey. McQuaid was incardinated, or transferred, from the Archdiocese of New York to this new diocese.[15] The pope named Bayley as its first bishop. Bayley appointed McQuaid in September 1853 as rector of St. Patrick's Pro-Cathedral in Newark.[16] In one of his first acts as rector, McQuaid recruited the Sisters of Charity to operate the orphanage attached to the cathedral.[17] He also played a leading role in establishing the Sisters of Charity of Saint Elizabeth as a diocesan community at Newark in 1859, becoming the Sisters' first superior general.[18]

President of Seton Hall College

When Seton Hall College opened in Madison in September 1856, McQuaid was appointed as its first president. Today it is Seton Hall University.[7] In the beginning, McQuaid directed a staff of three priests and five lay instructors teaching five seminarians. The enrollment grew to 54 by the end of the college's first year.[19] After serving one year as president of Seton Hall, McQuaid resigned to return to his position as rector at St. Patrick's Pro-Cathedral.

In 1859, Bayley allowed McQuaid to resume the presidency of Seton Hall while remaining rector of St. Patrick's Pro-Cathedral.[20] He also served as professor of rhetoric at the college, and was known as "a rigid disciplinarian [who] insisted on promptness and exactness in every detail."[21] In 1860, McQuaid moved Seton Hall from the Madison campus to South Orange, New Jersey, which was closer to the City of Newark.[22] McQuaid converted a large mansion on the new campus into a seminary and constructed a new brick building for the college.[22] The cornerstone of the new building was laid in May 1860 and the college reopened in September 1860 with 50 students.[23]

The American Civil War started on April 12, 1861, with the two-day Battle of Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. On the following Sunday, McQuaid addressed the congregation at St. Patrick's Pro-Cathedral, expressing his support for the federal government in this conflict.[24] The following week, the American flag was raised above the cathedral. McQuaid was invited to address a public meeting at the Rochester courthouse, where he declared that "this glorious Union would be sustained against any enemy, whether in our land or from a foreign country."[25]

During the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, Quaid traveled to Virginia to minister to wounded and dying soldiers; he was the only Catholic priest at the battlefield.[26] While in Virginia, he allegedly converted a Protestant soldier who witnessed him offering whisky to a fellow soldier.[27]

In September 1864, the newly ordained Reverend Michael Corrigan joined the faculty of Seton Hall. The two priests soon developed a lasting friendship. They would later emerge as the two most prominent conservative leaders among the American hierarchy.[28] As one historian described their relationship:

The McQuaid-Corrigan relationship developed at Seton Hall and so highly did McQuaid esteem the mind and administrative talents of the young Corrigan, that rightly or wrongly, McQuaid later would claim credit for Corrigan's advancement: first to Seton Hall, then to [Bishop of] Newark and finally his promotion to Archbishop of New York. After 1880, Corrigan was technically McQuaid's superior, but to the very end it remained the relationship of a former teacher to his pupil with McQuaid playing the role of friend, advisor and trusted confidant, who always encouraged Corrigan to act clearly, boldly and decisively.[29]

In January 1866, a fire destroyed the seminary building at Seton Hall. McQuaid quickly raised the funds to build the larger Immaculate Conception Seminary, which opened on the Seton Hall campus in 1867. .[30] In addition to his duties as college president and cathedral rector, Bayley named McQuaid as vicar general of the diocese in September 1866.[7] In his two years as vicar general, he became "a terror to delinquents"[31] regularly suspending priests for financial misdeeds, drunkenness, and insubordination.

McQuaid accompanied Bayley to the Second Plenary Council of Baltimore in October 1866, serving as Bayley's theologian and as a member of the Council's committee on bishops, priests, and seminarians.[32]

Remove ads

Bishop of Rochester

Summarize

Perspective

On March 3, 1868, McQuaid was appointed the first bishop of the newly created Diocese of Rochester by Pope Pius IX.[8] Archbishop John McCloskey of New York noted in a letter to Archbishop Martin John Spalding that McQuaid had been "determined not to accept, [and] had in this the sympathy and encouragement of his own Bishop, but he has finally yielded to considerations."[33] McQuaid received his episcopal consecration on July 12, 1868, from McCloskey, with Bayley and Bishop Louis de Goesbriand serving as co-consecrators, at St. Patrick's Old Cathedral in Manhattan.[8]

McQuaid formally took charge of the Diocese of Rochester on July 16, 1868, when he was installed in a temporary frame building that had been erected to accommodate Rochester's unfinished St. Patrick's Cathedral.[34][35] At the beginning of McQuaid's tenure in 1868, the diocese contained 54,500 Catholics, 39 priests, 35 parishes, and 29 missions.[36] In his final year as bishop in 1909, there were 121,000 Catholics, 164 priests, 93 parishes, and 36 missions.[37]

Conflicts with priests

Thomas O'Flaherty

McQuaid's disputes with other clergymen began early in his tenure. In February 1869, he tried to remove Reverend Thomas O'Flaherty from his position as pastor of Holy Family Parish in Auburn, New York, Concerned about the financial mismanagement of the parish, McQuaid demanded a financial statement from O'Flaherty. When the priest refused to provide it, McQuaid removed him from Holy Family.[38] However, O'Flaherty refused his new assignment, prompting McQuaid to suspend him from ministry.[39] The case received wide media coverage, especially from the The New York Freeman's Journal in Manhattan. McQuaid blamed its editor, James McMaster ,"for a great deal of the wrong judgment towards myself entertained by many Priests in distant parts of the U.S. with regard to my action in O'Flaherty's case."[40] Flaherty remained suspended until 1892.

Louis Lambert

Another prominent conflict involved Reverend Louis Lambert, pastor of St. Mary's Parish in Waterloo, New York. In addition to his pastoral work, Lambert had begun editing the Waterloo Catholic Times in 1877. McQuaid originally approved of Lambert's work at the newspaper. However, his opinion soured after the Catholic Times began to criticize him and other priests in the diocese. In April 1881, McQuaid restricted Lambert's ministry to his own parish, forced him to resign as editor of the Catholic Times. Lambert appealed McQuaid's ruling twice to the Vatican, but lost both times.[41]

In 1888, McQuaid tried to expel Lambert from the diocese. Lambert appealed again to the Vatican, forcing both him and McQuaid to travel to Rome for a hearing.[41] While waiting for a decision, McQuaid, complained about the bad publicity to Bishop Richard Gilmour in April 1889, "Here I am like a culprit snarled at by all the cheap Catholic newspapers of America from the Atlantic to the Pacific."[41] In January 1890, the Vatican ruled that Lambert would remain in the Diocese of Rochester, but must accept any assignment by McQuaid. Lambert was then assigned by McQuaid as pastor of Assumption Parish in Scottsville, New York, where he served until his death in 1910.[42]

Edward McGlynn

During the late 1880s, McQuaid advised Corrigan, now archbishop of New York, during his high-profile conflict with Reverend Edward McGlynn, a priest in the archdiocese. McGlynn was a social reformer who actively supported the economist Henry George and his "Single Tax" movement. McQuaid and Corrigan believed this philosophy contradicted Catholic teaching on the right to private property.[43] McQuaid encouraged Corrigan to be "clear, strong and bold, and not afraid"[44] when dealing with McGlynn and to prohibit Catholics in the archdiocese from attending meetings of McGlynn's Anti-Poverty Society.[44]Corrigan followed this advice and finally excommunicated McGlynn in July 1887.

Apostolic delegate

By the 1870s, Vatican officials were tired of dealing with the large number of disputes between priests and bishops in the United States, such as those between McQuaid, Lambert and O'Flaherty. This concern led early discussions of appointing an apostolic delegate to the United States who would have the authority to mediate these disputes. McQuaid opposed this idea from the start, writing to Corrigan in February 1877,

"The 'Apostolic Delegate' business is a very serious one, and one destined to make trouble if followed up. Instead of keeping up our own warm love for Rome, it will have a contrary effect. The only reason for the change that I have heard indicated has been to lessen appeals to Rome. Will he lessen them? I doubt it."[45]

While visiting Rome in late 1878, McQuaid vowed to "use all judicious efforts with all suitable persons from the Pope down to put a stop to this Delegate arrangement."[46] His efforts delayed the appointment of an apostolic delegate for 14 years. However, in 1892, Pope Leo XIII finally appointed Archbishop Francesco Satolli as the first apostolic delegate to the United States. That same year, McQuaid lifted O'Flaherty's suspension at Satolli's request. The only condition was that O'Flaherty could not resume ministry in Rochester.[47]

First Vatican Council

In late 1869, McQuaid arrived in Rome to participate in the First Vatican Council (1869-1870). The most important decree at the Council was that of papal infallibility. The doctrine stated that the pope was incapable of making a mistake on doctrine when speaking ex cathedra.[48]

McQuaid had theological reservations about papal infallibility and wanted the church to spend more time studying it. He criticize the haste to address "this most unnecessary question" at the Council.[48] On April 24, 1870, McQuaid wrote to the rector of St. Patrick's Cathedral:

Opposed to the definition are so many Bishops of unquestionable devotion to the Holy See, who will vote [against] if it should come before them that men stop to think. Besides the governments of Europe are alarmed. They remember that Popes in the past absolved subjects from their allegiance and in many ways interfered with governments. Even in our country there will arise more or less difficulty on this head. At least politicians will try to use the difficulty against us.[49]

At the opening session of the Council, McQuaid and a minority of bishops petitioned Pope Pius IX to withdraw the infallibility decree; it was denied.[50] The Council held a preliminary vote on the decree on July 13, 1870. McQuaid and 87 other bishops voted no, 451 voted yes, and 62 voted yes with conditions.[50] Ahead of the scheduled final vote on July 18th, many opponents of infallibility decided to skip that session; they did not want to offend the pope by opposing his decree.[51] After receiving permission to leave the Council, McQuaid left Rome the same day the decree passed.[52]

Back in Rochester at St. Patrick's Cathedral, McQuaid declared on August 28th, "I have now no difficulty in accepting the dogma, although to the last I opposed it."[53] However, despite his public acceptance of papal infallibility, his previous opposition was not forgotten by all. In June 1880, McQuaid mentioned to Corrigan:

"Two letters from Cardinal Simeoni indicated clearly that my adhesion to the Vatican Council can be questioned...My last letter to the Cardinal showed him plainly how I stood, but that I would not submit gracefully to the calling in question of my faith and honor at the instigation of unknown assailants."[54]

Catholic education

Since his time as a pastor and college president, McQuaid was particularly dedicated to the cause of Catholic education. In August 1872, he stated: "I have ever said that I would rather see the school house without the church than the church without the school house."[55] In his view, the parochial school was a spiritual necessity because "unless children are trained, nurtured, [and] schooled under Catholic influences and teachings, they will be lost to God's Church."[56] The public schools, he believed, was dominated by "the Protestant or the godless."[57] When McQuaid arrived in Rochester in 1868, the only true parochial schools were attached to five German parishes, which at that time educated 2,000 students.[58]

On his return from the First Vatican Council in 1870, McQuaid opened a minor seminary in Rochester to educated teenagers with an interest in the priesthood.[58] He first called it St. Patrick's, but renamed it as St. Andrew's Seminary in 1879.[59] In 1871, McQuaid announced his plan to create a system of tuition-free parochial schools in the diocese, staffed by the Sisters of St. Joseph.[60] At the time of his death in 1909, 53 of the diocese's 93 parishes had their own parochial school, with 18,000 total students.[37]

In 1874, McQuaid announced that the parents who failed to send their children to an available parochial school would be denied the sacrament of penance. The Congregation of the Holy Office at the Vatican, in a letter to American bishops in 1875, endorsed McQuaid's policy.[61] Also beginning in 1874, McQuaid directed the diocesan high schools to administer the New York Regents Examinations to its students. At that time, a passing score on the Regents exams was a graduation requirement in the public high schools. Quaid said that he wanted to "show to our own people and to others that our schools are as good and better than the state schools, even by their own tests."[62]

McQuaid in 1879 began planning a major seminary in the diocese for men ready to prepare for the priesthood.[58] He purchased a site in Rochester in 1887 and began construction four years later.[58] In September 1893, Saint Bernard's Seminary opened, with 39 seminarians and eight faculty members. The staff included Reverend Edward Joseph Hanna, a future archbishop of San Francisco, as professor of dogmatic theology and the theologian Reverend Andrew Breen as professor of Hebrew and Scripture.[63] McQuaid taught homiletics at the seminary.[64] Saint Bernard's became a national model and by 1910 had 233 seminarians, second in enrollment only to St. Mary's Seminary in Baltimore.[65]

Archbishop John Ireland

In the late 19th century, the conservative wing of American Catholic bishops was led by McQuaid, Corrigan, and Archbishop Frederick Katzer. This group favored strong adherence to Vatican policies and traditions.[66] Leaders of the liberal faction, meanwhile, included Archbishop John Ireland, Archbishop John J. Keane, and Cardinal James Gibbons.The liberal group was considered proponents of reform and adapting the church to American conditions.[66]

These ideological differences led to many public disputes between McQuaid and Ireland. Their feud became so pitched that when once asked if he would "bury the hatchet" with Ireland, McQuaid responded, "Yes, in his skull!"[41]

Catholic University of America

One of the early differences between McQuaid and Ireland was on the establishment of the Catholic University of America (CUA). Many bishops wanted to send their priests to a Catholic university in the United States rather than to ones in Europe. McQuaid expressed his misgivings about the proposal in 1882, describing it as premature.[67]

In 1884, the bishops attending the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore in Baltimore, Maryland, authorized its establishment.[65] The Council established a planning committee for CUA, which was dominated by Ireland and Keane. McQuaid soon learned that this committee was proposing Washington, D.C. as the site for the new university. McQuaid opposed that idea as would put the CUA close to Baltimore and Gibbons' influence.[65] When Corrigan confessed his own mistrust in the planning committee, McQuaid advised him to sever his connections with the CUA project.[44]

Catholic University was dedicated in 1889. McQuaid boycotted the ceremonies and refused to allow any collections for the CUA in his diocese.[65] When the Ancient Order of Hibernians began collecting for an endowed chair at the CUA, McQuaid remarked that it should be called the "Murderers' Chair"[28] because he believed Hibernians were connected to the Molly Maguires, a secret society in the Kingdom of Ireland. When Pope Leo XIII removed Keane as the CUA rector in 1896, McQuaid was elated. He told Corrigan,

"The news from Rome is astounding. The failure of the University is known in Rome at last...What collapses on every side! Gibbons, Ireland, and Keane!!! They were cock of the walk for a while and dictated to the country and thought to run our dioceses for us."[28]

Poughkeepsie Plan

McQuaid's animosity toward Ireland grew in 1890, when the latter addressed the National Education Association. In his speech, Ireland praised public schools and express his regret for the need for parochial schools.[68] While there, Ireland gave his support for the Poughkeepsie Plan, a local sharing of public and parochial school facilities, based on an arrangement in Poughkeepsie, New York. Under the plan, the school board in a community would control parochial schools during school hours while religious instruction occurred at the schools outside those hours.[69]

McQuaid opposed the Poughkeepsie Plan, believing that it compromised Catholic values. He said that it "weakens and deadens the Catholicity of our schoolrooms."[70] After Ireland tested the plan in Faribault and Stillwater, Minnesota, McQuaid described Ireland as "the head and front of the new liberalistic party in the American Church."[44] He further claimed that "as our arduous work of the last forty years was beginning to bear ample fruit, they arbitrarily upset the whole. If an enemy had done this!"[41]

SUNY Board

Tensions between McQuaid and Ireland reached a boiling point in 1894. With the death of Bishop Francis McNeirny in January 1894, the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York (SUNY) needed a Catholic board member. Two priests, Reverend Sylvester Malone and Reverend Louis Lambert, presented themselves as candidates to the New York State Legislature.[71]

McQuaid believed that both Lambert and Malone were too liberal to be on the SUNY board, so he announced announced his own candidacy. He told Corrigan, "All I care about is to defeat these two."[72] At this point, Ireland intervened to oppose McQuaid. Ireland convinced Lambert to withdraw his candidacy and successfully lobbied the legislature to appoint Malone to the SUNY board.[71]

Election of 1894

Later that year, Ireland actively campaigned for the Republican Party in the 1894 New York state election.[72] The election ended in a Republican victory along with the passage of the Blaine Amendment to the Constitution of New York, denying public funding to religious schools.[41] Ireland's involvement in New York politics enraged McQuaid, who declared that Ireland "has no sense of the propriety of things."[73]

On November 25, 1894, McQuaid denounced Ireland during a sermon at St. Patrick's Cathedral in Rochester. McQuaid described Ireland's actions as "undignified, disgraceful to his episcopal office" and saying "this scandal deserves rebuke as public as the offense committed."[74] After this public condemnation, McQuaid proudly told Corrigan, "It seems that Ireland and Keane were at Atlantic City the Sunday my sermon was delivered. They were hopping mad, and took no pains to conceal their anger."[41] The Vatican expressed its displeasure about the sermon to McQuaid. In a letter to Cardinal Mieczysław Halka-Ledóchowski explaining his actions, he declared:

Of late years, a spirit of false liberalism is springing up in our body under such leaders as Mgr. Ireland and Mgr. Keane, that, if not checked in time, will bring disaster on the Church. Many a time Catholic laymen have remarked that the Catholic Church they once knew seems to be passing away, so greatly shocked are they at what they see passing around them.[28]

Americanism

McQuaid's distrust of Americanism was vindicated by the Vatican in January 1899, when Pope Leo XIII issued the apostolic letter Testem benevolentiae nostrae. The letter condemned "Americanism" as a form of modernism that was undermining Catholic doctrine, trying to adapt the Church to Protestant culture.[75] In response, Ireland and his fellow liberals claimed that they held no such views.

In June 1899, during a sermon in Rochester, McQuaid rebutted the liberals. He stated that "there was a species of Americanism which the Holy Father had condemned prior to his encyclical."[28] He cited four examples involving Ireland, Keane, and Gibbons :

- Their attendance at the 1893 Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago, Illinois. McQuaid said that having Catholic prelates at the parliament put Catholicism on par with the "lowest forms of evangelicalism and infidelity;"

- Their support in 1890 for the Poughkeepsie Plan and "godless public schools"

- Their support for acceptance by the Catholic church of so-called "secret organizations" and their "hope that soon the ban would be raised from Freemasonry"

- Keane's 1890 lecture at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, meant allegedly "to advertise...the new born liberalism of the Catholic Church."[76]

Reconciliation

After Corrigan's death in 1902, McQuaid sought a reconciliation with Ireland.[66] Happy to oblige McQuaid, Ireland in December 1902 wrote: "McQuaid, too, is my staunch admirer. Le monde est a rebours [The world is upside down]."[28]

O-Neh-Da Vineyard

In 1872, McQuaid purchased a farm overlooking Hemlock Lake south of Rochester. He dedicated a portion of the land for use as a winery to produce sacramental wine for local churches. He named it "O-Neh-Da" after the Seneca name for the lake.[77] By 1905, the winery was producing 20,000 gallons of wine annually[78] McQuaid made the farm his second home and hosted guests such as Archbishop John Joseph Williams of Boston.[79] When the City of Rochester acquired Hemlock Lake and the surrounding properties for use as a reservoir, it demolished McQuaid's cottage along with other structures around the lake. However, the city allowed the continued operation of O-Neh-Da.[77]

Later life

McQuaid developed pneumonia in 1903, leading him convalesce in Savannah, Georgia into 1904.[80] In February 1904, McQuaid wrote to the Vatican, asking them to appoint Monsignor Thomas F. Hickey, his vicar general, as auxiliary bishop of Rochester.[81] Instead, Pope Pius X named Hickey as coadjutor bishop of the Rochester, with the right of succession. Hickey was consecrated on May 24, 1905.[58]

In 1907, Archbishop Patrick William Riordan wanted the Vatican to appoint Reverend Hanna from St. Bernard's Seminary as coadjutor bishop for the Archdiocese of San Francisco.[66] However, Cardinal Girolamo Maria Gotti at the Vatican received a letter challenging Hanna's orthodoxy, accusing him of modernism.[82] McQuaid defended Hanna to Gotti, saying:

"If this charge had any foundation, it would implicate St. Bernard's Seminary and myself. I know my professors well, as I am constantly with them, and I am sure that there is no tinge of unsoundness in their speech and thoughts."[66]

The modernism accusation derailed Hanna's appointment as coadjutor bishop. McQuaid later learned that Reverend Andrew Breen at St. Bernard's had written the letter to Gotti. In response, McQuaid dismissed Breen from the seminary.[83]

In McQuaid's last months, Ireland sent him a telegram, offering his "most sincere sympathy" to "the old hero". Reverend Louis Lambert, whom McQuaid had opposed in 1894 for the seat on the SUNY board, paid a visit to McQuaid.[84]

Death and legacy

McQuaid died at his residence in Rochester on January 18, 1909, two days after the 61st anniversary of his priestly ordination.[35] Following his death, the bell of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Rochester tolled 86 times, one for each year of his life.[85] McQuaid is buried at Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Rochester, which he founded in 1871.[84]

McQuaid Jesuit High School in Brighton, New York, was named after him.[86]

Remove ads

References

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads