Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Demes in the Byzantine Empire

Chariot racing factions From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The demes (Ancient Greek: δῆμοι, Latin: factiones) were chariot racing factions in the Roman and later Byzantine Empires, which over time developed into social and political factions. There were four demes; the dominant two were the Blues (Greek: Βένετοι, romanized: Vénetoi) and the Greens (Greek: Πράσινοι, romanized: Prásinoi), which exercised patronage over the Whites (Greek: Λευκοὶ, romanized: Leukoí) and the Reds (Greek: Ῥούσιοι, romanized: Rhoúsioi) respectively.[1]

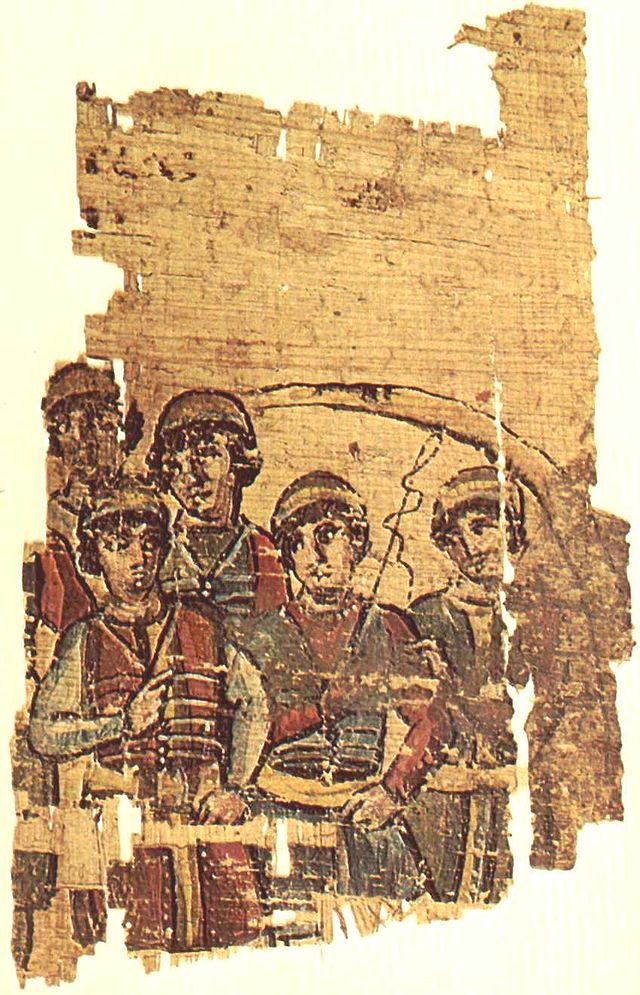

Charioteers of the Green, Red, White and Blue demes; part of a third-century AD mosaic in the Museo Nazionale Romano.

The demes began in the Principate era as chariot racing factions. With the decline of urban self-governance, they took on broader responsibilities such as organizing the spectacles. The colour divisions gradually covered other aspects of daily life such as theatre, so that by the fifth century they had become more akin to political parties.

Between the 5th and 8th centuries, the demes grew so powerful that they participated in the political and religious conflicts of the time,[2] terrorised the major Byzantine cities with their frequent riots (most notably the Nika riots in 532), had official militias,[3] made and unmade emperors, and were sometimes called on by the emperors for tasks like repelling invasions and repairing the city walls.[4] Entire neighbourhoods and guilds were described as pro-Blue or pro-Green. Theodore Balsamon, in his commentary on the Council in Trullo, noted that even the emperor had no authority over the demes.[5] However, beginning in the 7th century, the demes gradually weakened and became integrated into the imperial government.[1]

Despite no longer being a significant social force, they retained ceremonial functions for several centuries afterwards. The 10th-century treatise [[De Ceremoniis describes various ceremonial processions and festive events in which the factions participated, most importantly the imperial coronations, starting with that of Justin I in 518.

There is scholarly debate over the extent to which the demes remained mere sporting factions, and the extent to which they morphed into political parties and wielded political power. Alfred Rambaud and Alan Cameron are representative of historians who minimize the political participation and influence of the demes, while Fyodor Uspensky, Alexander Dyakonov, and Gavro Manojlović are representative of historians who maximize it.

Remove ads

Etymology

The factions were referred to in Greek using the word δῆμος (plural δῆμοι), which meant "people". There are two different opinions in scholarship about how the word for "people" came to also mean "circus factions". One position, that of Alan Cameron, is that it was a calque of the Latin populi, which meant both "people" and "members of a guild".[6] Another view, espoused by Constantin Zuckerman, is that both senses of the word δῆμοι (people and circus factions) actually referred to a specific class of citizens, who were entitled to public distributions of grain and who had an interest in public entertainment such as chariot racing.[7]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Origins

The origins of the demes lie in the Roman Republic, when certain individuals known as domini factionum would hire out horses and other necessary equipment and personnel to the agonothetes, who organised the chariot racing games. In practice, agonothetes could not organize games without them. After Nero increased the number of prizes and, consequently, races, the domini factionum began refusing to hire teams for less than a full day.[9] Under these conditions, maintaining teams that did not win imperial prizes became unprofitable, and small entrepreneurs ceased their activities. The domini, not the charioteers, were the primary force in their organizations. They were the ones capable of resolving conflicts. Suetonius recounts that when Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, Nero's father, refused to pay a winner, only a complaint lodged by the chariot owners forced him to relent.[10]

The organizations of the domini factionum took on contracts to arrange games; each had its own treasuries, menageries, permanent staff of charioteers, and actors. They were distinguished by the colours their charioteers wore. According to Tertullian, there were originally only the Reds and the Whites, representing summer and winter respectively. However, later, "due to increased luxury and the spread of superstitions," the Reds were dedicated to Mars, and the Whites to Zephyrus. He also mentions that the Greens were dedicated to Terra or spring, and the Blues to the sea and sky or to autumn.[11] According to sixth-century sources, like the chronicle of John Malalas and the dependent Chronicon Paschale, the circus factions represent the Solar System and correspond to the four elements: earth, water, fire, and air.[12] The Blues, Greens, Reds and Whites were established by the first century AD, with the first mention of them being by Pliny the Elder in 70.[13]

Since the death of Nero the charioteer of the Greens

has often won the palm, and carried off many prizes.

Go now, malicious envy, and say that you were influenced by Nero;

for now assuredly the charioteer of the Greens, not Nero, has won these victories.

The majority of the domini factionum were equites, and it concerned the senators that people of a lower class than them could earn so much wealth and power through the horse breeding industry. A series of laws were therefore passed to secure the imperial monopoly on the best horses. A law addressed to the prefect of Rome in 381 mandated that all winning horses be handed over to the city's residents, which ultimately undermined the financial incentive for private agonothetes.[15] By the 4th century, the horse racing industry, as well as that of the gladiatorial games, had been "imperialized", with administrative duties for organizing the games transferred to special imperial officials known as actuarii thymelae et equorum currilium. [16][17] In provinces where the emperor could not personally organize games, festivities were tied to the imperial cult, ensuring that no one could receive the peoples' gratitude except the emperor. Although the domini lost commercial interest in organizing games, they retained the responsibility of overseeing stables and training teams, which included, in addition to the charioteers themselves, a large number of support staff. In this capacity, they were called Latin: factionarius.[18]

It is commonly assumed that the Blues, Greens, Reds and Whites were equal once, but that the Blues and Greens slowly grew to dominate the Reds and Whites. However, from as early as the Julio-Claudians, almost every emperor whose favourite deme is known supported either the Blues (e.g. Vitellius, Caracalla) or the Greens (e.g. Caligula, Nero, Domitian, Lucius Verus, Commodus, Elagabalus). Marcus Aurelius stated that he was "neither Blue nor Green". From such evidence, some historians argue that the circus faction rivalry had always been between the Blues and Greens.[19]

From the 5th century onwards, the traditional faction colors spread to organizers of spectacles in theaters and amphitheaters. For example, Procopius recounts that the father of the future empress Theodora was a bear-keeper for the Greens.[20]

Origin myths

A more fanciful origin story of the demes is given by John Malalas, who says that, when Romulus saw that the Romans "were angry and resistant to him on account of his brother's death", he invented the factions to divide them against each other. "So the inhabitants of Rome were divided into factions, and no longer were in concord with each other, because they desired their own victory and devoted themselves to their faction as to some religion".[21] This myth, or a version of it, appears in several other chronicles, and in the writings of Isidore of Pelusium, who speaks of the demes as a political machination.[22]

Height

Despite beginning as mere sports fanclubs, the demes became involved with the political and even religious disputes of the time. For example, during the Chalcedonian Schism, the Blues generally aligned with the Chalcedonians and the Greens with the non-Chalcedonians. Chrysaphius and Theodosius II, who convened the Second Council of Ephesus, both supported the Greens, while Marcian, who convened the opposing Council of Chalcedon, supported the Blues.[23] However, this was not a solid rule, as there were many Chalcedonian Greens (like Maurice) and non-Chalcedonian Blues (like Theodora).[24]

There was a class division between the two demes. The Greens tended to be more working-class than the Blues, and were better represented among craftsmen, artisans, port-workers and countryfolk. Meanwhile, the Blues were better represented among elites and government officials, as well as the Jews. During the Nika Riots, a leader of the Greens sarcastically told Justinian that he did not know where the palace and government offices were.[23][25] Certain neighbourhoods (like Zeugma, now Unkapanı, and the quarter of Mazentiolos) were strongholds of the Greens, and others (like Pittakia and the quarters along the Mese) were strongholds of the Blues.[26]

After the death of Anastasius I Dicorus (who had supported the Reds) in 518, the excubitors hoped to make a man named John the next emperor, but were unable to because the Blues disapproved. Later, the Greens blocked Germanus's imperial ambitions on account of his favouritism towards the Blues. These incidents illustrate the growing power of the demes.[27][28] According to the contemporary chronicler Evagrius Scholasticus, in the leadup to the Nika Riots, Justinian favoured the Blues "to such an excess, that they slaughtered their opponents at mid-day and in the middle of the city, and, so far from dreading punishment, were even rewarded; so that many persons became murderers from this cause. They were allowed to assault houses, to plunder the valuables they contained, and to compel persons to purchase their own lives; and if any of the authorities endeavoured to check them, he was in danger of his very life".Scholasticus 1846

The Nika Riots in 532 are the deadliest and most famous of the many riots caused by the demes, but there were also other times when the Blues and Greens put aside their differences and united against the government. For example, in the famine-stricken year of 556, both demes jointly demanded bread from the emperor.[29] John Malalas records another incident,[note 1] in which the city prefect Zemarchus tried to arrest a young man from the Greens named Kaisarion, but for two days the Greens and Blues battled the imperial soldiers to protect him. Despite Justinian repeatedly sending excubitors as reinforcements, and all sides suffering heavy casualties, the Greens and Blues managed to push the soldiers to the Forum of Constantine, the Forum of Theodosius, and finally the praetorium. Justinian eventually pardoned them and dismissed Zemarchus.[31]

Accordiong to Theophanes the Confessor, when Justinian died, the quarrels between the demes reached such an extent that Justinian's successor, Justin II, told the Blues "The emperor Justinian is dead and gone from among you", and the Greens "The emperor Justinian still lives among you". This temporarily calmed the factions down, and the riots ceased.[32]

The demes caused disturbances not only in Constantinople, but as far away as Syria and Egypt. For example, according to John Malalas, in 490 the Greens started a pogrom and massacred the Jewish population of Antioch, until Theodore, the Prefect of the East, suppressed them. When Emperor Zeno, who was a supporter of the Greens, heard of it, he joked "Why did you burn only the dead Jews? It was necessary to burn the living Jews as well."[21] On another occasion, the Greens and Blues (Greek: πρασινοβενέτων) in Antioch rose up with the Judeo-Samaritan revolt of Julianus ben Sabar in 529, and killed their fellow Christians.[33][34] The Egyptian chronicler John of Nikiu wrote about the chaos caused by the demes in Egypt, such as the Aykelah revolt, while the monk Strategius complained that the Blues and Greens in Jerusalem were fighting each other and plundering Christians.[35] In 614, when the Persians besieged Jerusalem, the demes united against Patriarch Zacharias's decision to surrender the city, and during the Siege of Alexandria in 641, two rival Byzantine commanders, Menas and Domentianus, were supported by the Greens and Blues respectively.[36]

Militias

The demes had their own militias, the demotai (δημόται), with an official registry (κατάλογος). The militias had a small nucleus of registered members (in 602, there were 900 Blues and Whites, and 1500 Greens and Reds) but could mobilise many more in times of need.[37] On several occasions, they helped repair the Walls of Constantinople. When the walls were damaged by an earthquake on 26 January 447, the Blues and Greens supplied 16,000 men between them for the rebuilding effort, and restored the walls in a record 60 days.[38] The gate now known as Yeni-Mevlevihane-Kapısı was once called Πόλη τοῦ Ρουσίου, or "Gate of the Reds". According to Andreas David Mordtmann, it was named so because it was built by the Reds.[39]

The militias sometimes also helped the government repel foreign invasions. Theophanes the Confessor reports that, when Zabergan crossed the Anastasian Walls in 559, Belisarius drove him away using the imperial cavalry, the horses of all the citizens, and the horses of the Hippodrome.[4][note 2] The demotai similarly helped defend Constantinople when it was besieged in 626. Another example of the demotai being recruited by the government occurs in the chronicle of John of Antioch. During the Heraclian revolt in 610, when Phocas saw the fleet of Heraclius on the horizon, he ordered the Greens to guard the Harbours of Caesarion and Sophia, and the Blues to guard the quarter of Hormisdas. Heraclius later had the banner of the Blues burned in the Hippodrome to shame them for their treason.[42]

The extent of the demes' participation in the military is debated. While the majority of historians believe that it was significant, some historians (including Alan Cameron) argue that it was minimal.

Decline

Beginning in the 7th century, the demes gradually became official. The first mention of both demarchs (official leaders of a deme) and of an official registry of Blues and Greens dates back to 602, and occurs in the History of Theophylact Simocatta.[43] A certain John Crucis was appointed by Maurice as the leader of the Greens; he started a riot[note 3] and was later burned alive by Phocas, for which the Greens retaliated by setting fire to the praetorium.[44][45] John of Nikiu also names two demarchs who were active in Egypt during the Siege of Babylon Fortress in 640: Menas, the leader of the Greens, and Cosmas the son of Samuel, the leader of the Blues.

The turbulent events of the 8th–10th centuries — the Byzantine Iconoclasm and the rise and fall of the Isaurian, Amorian, and Macedonian dynasties — occurred without factional involvement. Lacking influence on public life, the factions continued their sporting activities. One faction still enjoyed greater imperial favor, with the Blues often preferred in the 9th–10th centuries. At the Hippodrome of Constantinople, they were the first to greet the emperor and held precedence over the Greens during ceremonies. Unlike in previous centuries, this situation no longer provoked discontent or led to conflicts.[46] Under Emperor Basil I (867–886), the factional phialae (platforms with fountains) built under Justinian II in the Great Palace were dismantled, making the distinctions between factions even less pronounced.[47][48]

In later centuries, the demes, whose leaders were appointed by the government, came to be subordinate to it. By 899, when the Klētorologion was written, only the Blues and Greens still existed. They separated further into those "of the city" (πολιτικοὶ·, politikoi), under a dēmarchos, and the "suburban" (περατικοὶ, peratikoi), under a dēmokratēs, a role which was entrusted to senior military officials: the Domestic of the Schools for the Blues, and the Domestic of the Excubitors for the Greens.[49] Their salaries were paid by the praipositos, and they had dedicated places in the Hippodrome, in the Great Palace and in imperial processions.[1] Ceremonies involving demarchs in this capacity are described by Constantine Porphyrogenitus in the 10th century, Michael Attaleiates in the 11th century and Theodore Prodromos in the 12th century.[50]

The official use of the title of dēmarchos (usually in conjunction with another office like symponos or logariastēs) continued even after the demes themselves disappeared. The dēmarchoi served as military commanders during the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.[1]

Remove ads

Modern parallels

The Blues and Greens are often compared to modern-day football hooligans. The Internet Medieval Sourcebook noted some similarities to the rivalry between Glasgow's two Old Firm football clubs: Celtic and Rangers. Celtic fans wear green to support their team, while Rangers fans wear blue. Their rivalry had religious and political aspects, with Celtics fans being generally Catholic and voting Labour, and Rangers fans being Protestant and voting Conservative.[51]

Notes

- Greek: Πέμψας τινὰς τῶν κομενταρησίων Ζίμαρχος ὁ ἔπαρχος ἐπὶ τῷ κρατῆσαί τινα νεώτερον ὄνομα Καισάριον, ἀντέστησαν οἱ τῆς γειτονίας τῶν Μαζεντιόλου καὶ ἐκύλλωσαν πολλοὺς στρατιώτας καὶ αὐτούς γε μὴν τοὺς κομενταρησίους... καὶ οὐ συνέβαλον μετὰ τῶν πρασίνων οἱ τοῦ βενέτου μέρους, ἀλλ' ἦν ἡ μάχη αὐτῶν μετὰ τῶν ἐξσκουβιτόρων καὶ τῶν στρατιωτῶν.[30]

- "Belisarius took every horse, including those of the emperor, of the Hippodrome, of religious establishments, and from every ordinary man who had a horse."[40] (Greek: ὁ δὲ Βελισάριος ἔλαβε πᾶσαν τὴν ἵππον, τήν τε βασιλικὴν καὶ τοῦ ἱππικοῦ καὶ τῶν εὐαγῶν οἴκων καὶ παντὸς ἀνθρώπου, ὅπου ἦν ἵππος)[41]

- This riot was so notorious it was mentioned by the author of the Doctrina Jacobi, who wrote "When Phocas became emperor in Constantinople, as a Green I betrayed Blue Christians, and denounced them as Jews and mamzirs. And when the Greens under Crucis burnt the Mese and perpetrated evil, as a Blue I again beat up Christians, insulting them as Greens and denouncing them as incendiaries and Manichaeans."[44]

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads