Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

1970s South Bronx building fires

Series of fires in New York City, USA From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

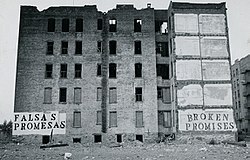

The 1970s South Bronx building fires, often referred to as simply the Bronx fires, were a series of fires that severely damaged the South Bronx and destroyed more than 80 percent of the buildings in the area.[1][2][3][4] The Bronx fires were the most damaging case of the high rates of fire and arson afflicting cities across America during the 1970s.[5]

Most fires were the result of arson, usually caused by landlords recruiting Bronx residents to start them,[6][7][8] but the South Bronx fires were not a singular, coordinated event. Rather, the fires were the result of multiple social and economic factors, spanning several decades. These factors include redlining and housing segregation, the economic crises of the 1970s, newly available property insurance programs, poor fiscal management by the city of New York, budget cuts targeted towards poor communities, the overcrowding of already-neglected areas due to gentrification, and many others.

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Demographic changes

By the end of World War II, many middle-class black and stateside Puerto Rican families had moved into the South Bronx from Harlem, as the Bronx was less populated and also legally integrated. However, many white Bronx residents left when non-white people moved in, fearing their properties would go down in value.[9] The construction of Co-op City motivated further flight by housing middle-class black and Puerto Rican residents in family-sized apartments. As a result, the South Bronx went from being two-thirds non-Hispanic white in 1950, to being two-thirds black or Puerto Rican ten years later.[10] Nationwide perception of the Bronx began to change from one of industry to one of slum, despite many other parts of New York also needing renovation; this perception which was brought into the policy world in 1938, when maps published by the FHA designated the buildings as deteriorating.[11][4]

As a result of these demographic changes, the South Bronx began to see reduced economic activity, as well as a decrease in funding for municipal services such as hospitals and public utilities. Many began to see the area as an economic drain, because despite holding jobs, many new South Bronx residents relied on some form of welfare.[10] By the 1960's, many landlords had begun to completely neglect their buildings, and the area had been substantially redlined. The completion of the Cross Bronx Expressway in 1963 caused further inconvenience for the area, in some cases displacing entire neighborhoods. Combined with Robert Moses's urban renewal projects, the value of buildings in the Bronx dropped dramatically, businesses left, income levels dropped, and crime began to rise.[4][12][13][14]

Population growth

Despite economic challenges, the South Bronx's population grew rapidly during the 1960s. Some of this was due to childbirth, but the majority of this growth was caused by the "urban renewal" project displacing residents from other parts of the city. Contributing massively to this push was Columbia University's rapid buy-up of low-income housing in Harlem, from which they kicked residents in order to create university dorms and housing.[15] The rapid influx of displaced New Yorkers caused the South Bronx's population to surge by over 100,000 in just a few years, putting a massive strain on the area's resources, which had already started to be cut and defunded by the city.[16]

City planning

After the production boom of World War II began to wane, New York City faced financial trouble. The city was described as "so broke" by the 1970s, with neighborhoods that had become "so desperate and depleted," that municipal authorities had to scramble for a solution.[17] Some policymakers believed the process of population decline was inevitable, and instead of trying to fight decline, searched for alternative approaches; in many cases, this resulted in attempts to have the greatest population loss in the areas with the poorest and non-white populations.[18][19]

Planned shrinkage

Roger Starr, former head of New York City's Housing and Development Administration, proposed a policy for addressing the economic crisis, which he termed planned shrinkage.[20] The plan's goal was to reduce the poor population in New York City and better preserve the tax base; according to the proposal, the city would stop investing in troubled neighborhoods, and divert funds to communities that could "still be saved."[20][21] Starr suggested that the city "accelerate the drainage" in what he called the "worst parts" of the South Bronx, and encouraged the city to do so by closing subway stations, firehouses, and schools.[22] According to its advocates, the planned shrinkage approach would encourage so-called "monolithic development," resulting in new urban growth at much lower population densities than the neighborhoods which had existed previously.[18] However, the policy was seen by many as ultimately failing to address the underlying systemic causes that were responsible.[23]

The ethics of this approach also came into question,[3] with former mayor Abraham Beame disavowing the idea, and City Council members calling it "inhuman," "racist," and "genocidal."[24] Abraham Beame soon dismissed Starr from his role in the HDA.[20] On top of depriving the South Bronx of adequate fire service and protection, planned shrinkage heavily hurt public health as well.[19][13][14] While the implementation of planned shrinkage policy was relatively short-lived,[25] the impact of the policy changes would last for the next two decades.[citation needed]

RAND Study

In the early 1970s, a RAND study examining the relation between city services and large city populations concluded that when services such as police and fire protection were withdrawn, the number of people in the neglected areas decreased.[3][19] Rather than linking this data to factors such as increased risk of death, the report avoided any connection to public health. Instead, the report built on existing prejudices established by reports such as the Moynihan Report, which argued that social issues facing black Americans were not systemic, but rather the result of black social and family organization in America.[26]

The RAND report further accelerated the growing cultral trend of blaming individuals affected by policy for their poverty, rather than criticizing policies themselves.[27] The RAND report in particular suggesting that neighborhood fires were predominantly caused by arson, despite substantial evidence that arson was not a major cause.[28] If arson was a primary cause, according to the RAND viewpoint, the city should not invest any further funds into improving fire protection. The RAND report allegedly influenced then-Senator Daniel Moynihan, author of the aforementioned report blaming minority groups for their financial circumstances. Moynihan used the report's findings to make recommendations for urban policy, arguing that arson was one of many social pathologies caused by large cities, and suggested that a policy of "benign neglect" was the most appropriate response.[18]

Remove ads

The fires

Summarize

Perspective

Timeline

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2025) |

- 1960s: First wave of fires. Landlords sold their buildings to new people who chopped them up into smaller and smaller sections, and then neglected them, didn't do necessary renovations, or even fill water boilers.[11][4] Also, new electronics came into the home during this time, which the buildings weren't built for.[29][6]

- 1968: First massive fire.

- 1969: New York City begins targeting poor and dense areas for service reduction.[19]

- 1972: Fires every 45 minutes.[30]

- 1974-1976: 12 fire companies are closed in the South Bronx due to budget cuts and the near-bankruptcy of the city [1]

- Mid-1970s: the Bronx had up to 130,000 fires per year, or an average of 30 fires every 2 hours. 40 percent of the housing in the area was destroyed, and the response time for fires also increased, as the firefighters did not have the resources to keep responding promptly to numerous service calls. According to one report, of the 289 census tracts within the borough of the Bronx, seven census tracts lost more than 97% of their buildings, with 44 tracts losing more than 50% of their buildings, to fire and abandonment.[4][11]

- Late 1970s: More than 40 fires a day.[4]

- 1977: A Bronx fire is accidentally televised during the 1977 World Series.

- 1977: President Jimmy Carter visits the Bronx.[31]

- 1981: Fort Apache, The Bronx is released, further pushing negative stereotypes blaming Bronxites for the fires.

- 1982: A Bronx arson unit was finally developed.[6]

- 1986: Mayor Ed Koch funds a $4.4 billion dollar program to rehabilitate 100,000 housing units.[1]

Attitudes of involved persons

Views towards the fires and the people affected by them were informed both by personal connections, and by societal bias and perception. Fires became so commonplace that residents and firefighters alike began to grow accustomed to them, and developed stronger feelings towards each other in the process. Firefighters often had negative views towards Bronxites of color[30][6][32], a view that was exacerbated by the fact that fire staff were almost entirely white. Firefighters were often described as showing apathy towards residents; one firefighter interviewed on Man Alive is quoted as saying "we have no sympathy, but we'll help"[30]. This view was influenced by public perception of Bronxites as well, since firefighters most often came from outside the Bronx, and federal funding for the South Bronx was seen as a waste.[10] As a result of the comportment firefighters displayed, many Bronxites of color didn't trust them, often seeing them as doing more damage than necessary[30].

Kids in particular shaped views of firefighters. In some cases, children pulled fire alarms as pranks, wasting firefighter time. In other cases, kids were responsible for the fires themselves, although these examples were most often due to the kids being paid to do so by landlords.[30][33][8].

Bronx residents became heavily accustomed to the fires. In an interview with the Bronx photographers los seis, members commented that "building after building, block after block was disappearing," and that they "...grew up always smelling wood [and] metal burning," noting that Bronxites would "...always hear firetrucks zooming by at all hours of the night.”[34] [35]

Role of landlords

Burning for insurance money was primarily driven by property owners who found that almost all of the property in the South Bronx had been redlined by the banks and insurance companies. Unable to sell their property at a good price and facing default on back property taxes and mortgages, some landlords began to burn their buildings for their insurance value. A type of sophisticated white collar criminal known as a "fixer" sprung up during this period, specializing in a form of insurance fraud that began with buying out the property of redlined landlords at or below cost, then selling and reselling the buildings multiple times on paper between several different fictitious shell companies under the fixer's control, artificially driving up the value incrementally each time.[28]

Fraudulent "no questions asked" fire insurance policies, including from the New York FAIR Plan, would then be taken out on the overvalued buildings and the property stripped and burnt for the payoff,[4][6][1][7] especially from Lloyd's of London.[36] This scheme became so common that local gangs were hired by fixers for their expertise at the process of stripping buildings of wiring, plumbing, metal fixtures, and anything else of value and then effectively burning it down with gasoline. Many finishers became extremely rich buying properties from struggling landlords, artificially driving up the value, insuring them and then burning them.[28] Often, the properties were still occupied by subsidized tenants or squatters at the time, who were given short or no warning before the building was burnt down. They were forced to move to another slum building, where the process would usually repeat itself. The rate of unsolved fatalities due to fire multiplied sevenfold in the South Bronx during the 1970s, with many residents reporting being burnt out of numerous apartment blocks one after the other.[28]

Other landlords profited simply by letting their buildings get damaged and start decaying, while still collecting rent.[11] As an added benefit to the landlord, burning older buildings and allowing erosion of decaying properties also helped other, better-maintained properties increase in value.[11]

Role of residents

While most arsons were driven by landlords, many of whom did not live in the area, HUD and city policies did encourage some local South Bronx residents to burn down their own buildings. Under the regulations, Section 8 tenants who were burned out of their current housing were granted immediate priority status for another apartment, potentially in a better part of the city. After the establishment of Co-op City, several tenants burnt down their Section 8 housing in an attempt to jump to the front of the 2-3 year long waiting list for the new units.[37] However, this housing was often in poor condition to begin with, and in many cases barely inhabitable.[6][11]

Due to the poor quality of housing and heavily-neglected buildings, many tenants began refusing to pay rent altogether.[38][39] Although rent strikes in the Bronx initially started due to the exorbitant rises in rent from absentee landlords, the practice of rent strikes soon spread to tenants of all neglected buildings, and led to periods where buildings remained untouched and rents unpaid for years on end.

Remove ads

Response and aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

Local response

Initially, residents applied to the city for funds, but were often ignored. By the end of the 1970's, Bronxites had begun to rebuild on their own, and began making recovery programs. Additionally, many of the buildings had been so long abandoned by landlords, and changed hands so many times, that the true owner was no longer known.[39] As such, many Bronx residents felt that repairing a building would ultimately make it theirs, as a product of the "sweat equity" put in. Groups such as the People's Development Corporation, formed in 1975 by Ramon Rueda, worked to "train residents to rebuild their own neighborhood... harnessing government work programs, available grants, and abandoned buildings."[40] The PDC was one of many groups that formed during the time;[39] other rehabilitation groups of the 1970s and early 1980s included BronxWorks (1972), the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition (1974), the Fordham Bedford Housing Cooperation (1980), the Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association (1982), and ¡Nos Quedamos! (1982).[40]

During this same period, gangs formed, and were looked to for protection by Bronx residents.[41] However, some argue that gang activity encouraged further white flight, prolonging the crisis.[39][41]

State response

By the 1980's, in line with president Reagan's goal of privatization, many New Yorkers felt that the best approach to solving the housing crisis was to privatize housing in the Bronx. This movement was spearheaded by Mayor Ed Koch.[42] Ultimately, arson rates did decline, but the era of modern gentrification was kicked off.[42]

National response

On a national level, politicians were seen by Bronxites as dragging their feet. However, the city of New York was already seen by the rest of the country as a massive drain. These mentalities were encapsulated by the infamous but misleading "Ford to City: Drop Dead" headline ran by the Daily News in 1976.[43] Just a year earlier, president Ford exacerbated the NYC budget cuts by refusing to send aid to the city.[43][6] The fires in the Bronx soon became a national discussion, however, when ABC’s aerial camera panned out over the stadium into the Bronx during the 1977 World Series, showing 60 million viewers a burning apartment building.[6]

In the aftermath, President Carter went to the Bronx[31][10] and made promises for recovery. Many other politicians visited the South Bronx to make political points, but this was largely seen as being for show.[6]

"The Bronx is Burning"

The phrase "The Bronx is burning" is often attributed to Howard Cosell during Game 2 of the 1977 World Series featuring the New York Yankees and Los Angeles Dodgers. During the game, as ABC switched to a helicopter shot of the exterior of Yankee Stadium, an uncontrolled fire could clearly be seen burning in the area surrounding the park.[6] Many believe Cosell then said "ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning,"[44], but review of the game footage shows that he did not say this. Both commentators did touch on the fires, but the words used by the two broadcasters during the game were later "spun by credulous journalists" into the now ubiquitous phrase without either of them actually having phrased it that way.[28]

Remove ads

Recovery and legacy

This section needs expansion with: impact of co-ops[45][46] and music on building community recovery efforts, and how the impact of crack, mass policing, and gentrification compiled on top of the impact of the fires. You can help by adding to it. (April 2025) |

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads