Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Coeliac disease

Autoimmune disorder that results in a reaction to gluten From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Coeliac disease (Commonwealth English) or celiac disease (American English) is a chronic autoimmune disease, mainly affecting the small intestine, and is caused by the consumption of gluten. Coeliac disease causes a wide range of symptoms and complications that can affect multiple organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract.

The symptoms of coeliac disease can be divided into two subtypes, classic and non-classic. The classic form of the disease can affect any age group, but is usually diagnosed in early childhood and causes symptoms of malabsorption such as weight loss, diarrhoea, and stunted growth. Non-classic coeliac disease is more commonly seen in adults and is characterized by vague abdominal symptoms and complications in organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract, such as bone disease, anemia, and other consequences of nutritional deficiencies.

Coeliac disease is caused by an abnormal immune system response to gluten, found in wheat and other grains such as barley and rye. When an individual with a genetic predisposition to coeliac disease consumes gluten, it triggers an inflammatory response in the small intestine, damaging the intestinal lining, leading to malabsorption. The development of coeliac disease is believed to be influenced by other environmental factors, such as infections.

Coeliac disease is diagnosed based on symptoms, blood tests, and biopsies of the small intestine while consuming a diet containing gluten. In those who have already reduced their gluten intake, reintroducing gluten may be required to reach an accurate diagnosis. The diagnosis is often complicated by the diverse symptoms, overlap with other disorders, and lack of awareness, leading to a delay in diagnosis. Current research indicates that there is not enough evidence to advocate for mass screening for coeliac disease in those without symptoms.

The only treatment for coeliac disease is a lifelong gluten-free diet (GFD). A GFD involves removing all food and drink which contain wheat, rye, barley and gluten derivatives. Symptoms can improve within days of adopting a GFD and the diet improves quality of life, prevents further complications and normalizes some effects of the disease such as stunted growth.

Approximately 1 in 200 to 1 in 50 people have coeliac disease. Diagnoses of coeliac disease has increased in recently due to increased awareness and availability of blood testing. However, the disease is still thought to be underdiagnosed, with a significant number of people with coeliac remaining undiagnosed and untreated. Most people develop the coeliac disease before the age of 10 and it is slightly more common in women than in men.

Remove ads

Terminology and classification

Summarize

Perspective

"Coeliac disease" is the preferred spelling in Commonwealth English, while "celiac disease" is typically used in North American English.[1][2]

The terms sprue, coeliac sprue, gluten-sensitive enteropathy, non-tropical sprue, idiopathic steatorrhoea, and gluten intolerance, have been used as synonyms for coeliac disease in the past. Both gluten intolerance and gluten sensitivity have been used as synonyms of coeliac disease or to describe other symptoms triggered by gluten, however the terms are non specific and lack and consistent definition.[3]

Gluten related disorders are conditions related to gluten such as coeliac disease, gluten ataxia, wheat allergy, dermatitis herpetiformis, and non-coeliac gluten sensitivity.[4]

Many individuals with coeliac disease are asymptomatic,[5] meaning they do not have any symptoms associated with coeliac disease. Those with asymptomatic coeliac disease are commonly diagnosed through screening programs. The term "silent coeliac disease" is equivalent to asymptomatic but usage is discouraged.[3]

Coeliac disease can be symptomatic (previously called "overt coeliac disease) or subclinical.[3] [5] Subclinical coeliac disease has historically had many different definitions such as those with symptoms mainly outside of the gastrointestinal tract, or those with clinical signs of the disease (anemia, laboratory abnormalities, and endoscopic features) but no symptoms. Subclinical coeliac disease is now used when individuals who don't have symptoms that commonly warrant testing for coeliac disease have positive serology for coeliac disease.[3] Symptomatic coeliac disease (characterized by symptoms related to gluten) can be further categorized into classical and non-classical.[5] Classical coeliac disease, which has also been called typical coeliac disease in the past, is coeliac disease presenting with malnutrition, malabsorption, and diarrhoea. Non-classical coeliac disease, historically referred to as atypical coeliac disease, is when individuals primarily present with symptoms unrelated to malabsoption.[3]

Potential ceoliac disease refers to those who have positive serology for coeliac disease but no changes in the small intestine. The term "latent coeliac disease" has been used interchangeably with potential coeliac disease, but has no consistent definition and its use is therefore discouraged.[3]

Sometimes, those with coeliac disease will continue to experience symptoms or signs of the disease despite being on a gluten free diet. "Slow responders" or "non responsive coeliac disease" (NRCD) is the persistence of symptoms despite exclusion of gluten for 6-12 months. [6][7] Refractory coeliac disease (RCD) is the persistence of malabsorption and damage to the small intestine after at least 12 months of a gluten free diet. Most people with NRCD do not have RCD and instead their symptoms are caused by some other factor. There are two types of RCD, type one has histopathological changes similar to those seen in untreated coeliac disease while type two has abnormal histopathological changes not consistent with untreated coeliac disease.[7]

Remove ads

Signs and symptoms

Summarize

Perspective

Coeliac disease causes a wide range of symptoms and complications that can involve several different organs.[5] The presentation of coeliac disease can be classified as classic, non-classic, and subclinical.[8] Classic coeliac disease is commonly seen in young children, but can affect any age group, and is characterized by malabsorption manifesting as diarrhoea, weight loss, and failure to thrive.[5][9] Non-classic coeliac disease is seen more often in adults and symptoms primarily manifest outside of the intestine (extraintestinal).[9] Many undiagnosed individuals who consider themselves asymptomatic are, in fact, not, but rather have become accustomed to living in a state of chronically compromised health. After starting a gluten-free diet and subsequent improvement becomes evident, such individuals are often able to retrospectively recall and recognise prior symptoms of their untreated disease that they had mistakenly ignored.[10][11][12]

Gastrointestinal

Diarrhoea that is characteristic of coeliac disease is chronic, sometimes pale, of large volume, and abnormally foul in odor. Other symptoms of coeliac disease include abdominal pain, cramping, bloating with abdominal distension, and mouth ulcers.[13][14] As the bowels become more damaged, lactose intolerance can develop.[15] Frequently, the symptoms are ascribed to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), only later to be recognised as coeliac disease.

Extraintestinal manifestations

Coeliac disease is a systemic disorder, meaning it affects the entire body. Although many common symptoms of the disease are related to the gastrointestinal tract, those with coeliac disease may also experience symptoms and complications in other organs, known as extraintestinal manifestations.[16] These manifestations may be related to malabsorption or systemic inflammation.[17] Common extraintestinal manifestations of coeliac disease include headaches, fatigue, brain fog, muscle pain, and joint pain.[17][18]

Nutritional status in coeliac disease may be compromised due to lower intake, maldigestion and malabsoprtion leading to nutritional deficiencies. Common deficiencies in coeliac disease include iron, folate, zinc, vitamin D, and vitamin B12.[14][18] Vitamin D deficiency can cause secondary hyperparathyroidism. Hyperoxaluria and kidney stones can be caused by malabsorption of fats and peptides.[18] Iron deficiency may lead to anemia, which is one of the most common extraintestinal presentation of coeliac disease.[17]

Coeliac disease often effects the bones, causing low bone mass density (osteopenia) and osteoporosis. Causes of bone changes in coeliac disease are believed to be caused by malabsorption, inflammation and autoimmunity.[16]

If left untreated, coeliac disease can affect hormones, causing delayed periods or puberty and reproductive disorders.[14][16] Coeliac disease is associated with infertility and complications during pregnancy such as intra-uterine growth restriction and spontaneous abortion. Reproductive disorders are thought to be caused by nutritional deficiencies, particularly zinc, iron, folate and selenium deficiencies in coeliac disease.[18]

Miscellaneous

Coeliac disease has been linked with many conditions. In many cases, it is unclear whether the gluten-induced bowel disease is a causative factor or whether these conditions share a common predisposition.[17][18]

- IgA deficiency is present in 2-2.5% of people with coeliac disease, and is itself associated with an increased risk of coeliac disease.[19]

- Dermatitis herpetiformis, an itchy cutaneous condition that has been linked to a transglutaminase enzyme in the skin. Enteropathy is commonly seen in dermatitis herpetiformis; however, gastrointestinal symptoms are rare.[18]

- Growth failure and/or pubertal delay in later childhood can occur even without obvious bowel symptoms or severe malnutrition.[13]

- Reproductive disorders such as delayed puberty, lack of menstruation, early menopause, infertility, miscarriage and intrauterine growth restriction are increased in coeliac disease.[18]

- Hyposplenism (a small and underactive spleen) can occur and may predispose to infection given the role of the spleen in the immune system.[18]

- Abnormal liver function tests (randomly detected on blood tests) may be seen.[14]

- Depression, anxiety and other mental health disorders.[17]

Coeliac disease is associated with several other medical conditions, many of which are autoimmune disorders: diabetes mellitus type 1, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, microscopic colitis, gluten ataxia, psoriasis, vitiligo, autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and more.[14][18]

Complications

Coeliac disease leads to an increased risk of both adenocarcinoma and lymphoma of the small bowel (enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma or other non-Hodgkin lymphomas) within the first year of diagnosis.[14] Whether a gluten-free diet brings this risk back to baseline is unclear.[20] Long-standing and untreated disease can rarely lead to other complications, such as ulcerative jejunitis (ulcer formation of the small bowel).[21]

Remove ads

Causes

Summarize

Perspective

Coeliac disease is caused by an inflammatory reaction to gliadins and glutenins (gluten proteins)[22] found in wheat and to similar proteins found in the crops of the tribe Triticeae (which includes other common grains such as barley and rye) and to the tribe Aveneae (oats).[23] Wheat subspecies (such as spelt, durum, and Kamut) and wheat hybrids (such as triticale) also cause symptoms of coeliac disease.[24]

A small number of people with coeliac disease react to oats. Sensitivity to oats in coeliac disease may be due to cross-contamination of oats and other foods with gluten, differences between gluten content, immunoreactivity, and genetic variability seen between oat cultivars or dietary intolerance to oats.[25][26] Most people with coeliac disease do not have adverse reactions to uncontaminated or 'pure' oats, however clinical guidelines differ on whether those with coeliac disease should consume oats.[27][28]

Other cereals such as maize, millet, sorghum, teff, rice, and wild rice are safe for people with coeliac disease to consume, as well as non-cereals such as amaranth, quinoa, and buckwheat. Noncereal carbohydrate-rich foods such as potatoes and bananas do not contain gluten and do not trigger symptoms.[29][30]

Risk modifiers

Environmental factors such as infections, geographic latitude, birth weight, antibiotic use, intestinal microbiota, socioeconomic status, hygiene, breastfeeding, and the timing of introduction of gluten into an infant's diet are theorized to contribute to the development of coeliac disease in genetically predisposed individuals.[7][22][9] The consumption of gluten and timing of introduction in a baby's life does not appear to increase the risk of coeliac disease, however in those who are genetically predisposed to coeliac disease, large amounts of gluten early in life, may increase the risk of developing coeliac disease.[31][32]

Mechanism

Summarize

Perspective

Coeliac disease appears to be multifactorial, both in that more than one genetic factor can cause the disease and in that more than one factor is necessary for the disease to manifest in a person.[33]

Almost all people (90%) with coeliac disease have either the variant HLA-DQ2 allele or (less commonly) the HLA-DQ8 allele.[8] However, about 40% of people without coeliac disease have also inherited either of these alleles.[34] This suggests that additional factors are needed for coeliac disease to develop; that is, the predisposing HLA risk allele is necessary but not sufficient to develop coeliac disease. Furthermore, around 5% of those people who do develop coeliac disease do not have typical HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 alleles.[8][35]

Genetics

The vast majority of people with coeliac have one of two types (out of seven) of the HLA-DQ protein.[8] HLA-DQ is part of the MHC class II antigen-presenting receptor[37] (also called the human leukocyte antigen) system and is used by the immune system to distinguish between the body’s own cells and others.[38][39] The two subunits of the HLA-DQ protein are encoded by the HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 genes, located on the short arm of chromosome 6.[40]

There are seven HLA-DQ variants (DQ2 and DQ4–DQ9). Over 95% of people with coeliac disease have the isoform of DQ2 or DQ8, which is inherited in families. The reason these genes produce an increase in the risk of coeliac disease is that the receptors formed by these genes bind to gliadin peptides more tightly than other forms of the antigen-presenting receptor. Therefore, these forms of the receptor are more likely to activate T lymphocytes and initiate the autoimmune process.[40]

Most people with coeliac bear a two-gene HLA-DQ2 haplotype called DQ2.5. This haplotype is composed of two adjacent gene alleles, DQA1*0501 and DQB1*0201, which encode the two subunits, DQ α5 and DQ β2.[41][42] In most individuals, this DQ2.5 isoform is encoded by one of two chromosomes 6 inherited from parents (DQ2.5cis). Most coeliacs inherit only one copy of this DQ2.5 haplotype, while some inherit it from both parents; the latter are especially at risk of coeliac disease as well as being more susceptible to severe complications.[43] The frequency of coeliac disease haplotypes can vary by geography.[33][44]

Some individuals inherit DQ2.5 from one parent and an additional portion of the haplotype (either DQB1*02 or DQA1*05) from the other parent, increasing risk. Less commonly, some individuals inherit the DQA1*05 allele from one parent and the DQB1*02 from the other parent (DQ2.5trans), and these individuals are at similar risk of coeliac disease as those with a single DQ2.5-bearing chromosome 6.[43][40] Among those with coeliac disease who do not have DQ2.5 (cis or trans) or DQ8 (encoded by the haplotype DQA1*03:DQB1*0302), 2-5% have the DQ2.2 isoform, and the remaining 2% lack DQ2 or DQ8.[43]

Other genetic factors have been repeatedly reported in coeliac disease; however, involvement in the disease has variable geographic recognition. Only the HLA-DQ loci show a consistent involvement over the global population. Many of the loci detected have been found in association with other autoimmune diseases.[35]

The prevalence of the HLA-DQ2 genotype and gluten consumption has increased over time. Since untreated coeliac disease can cause serious health problems and affect fertility, it would be expected that HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 would become less common. The opposite is true—they are most common in areas where gluten-rich foods have been eaten for thousands of years.[45] The HLA-DQ2 gene may have been genetically favoured in the past because it helps protect against tooth decay.[44][46]

Prolamins

Most of the proteins in food responsible for the immune reaction in coeliac disease are prolamins. These are storage proteins rich in proline (prol-) and glutamine (-amin) that dissolve in alcohols and are resistant to proteases and peptidases of the gut.[47] Prolamins are found in cereal grains with different grains having different but related prolamins: wheat (gliadin), barley (hordein), rye (secalin) and oats (avenin).[23][8]

Membrane leaking permits[clarification needed] peptides of gliadin that stimulate two levels of the immune response: the innate response and the adaptive (T-helper cell-mediated) response. One protease-resistant peptide from α-gliadin contains a region that stimulates lymphocytes and results in the release of interleukin-15. This innate response to gliadin results in immune-system signalling that attracts inflammatory cells and increases the release of inflammatory chemicals.[49][needs update?]

The response to the 33mer occurs in most coeliacs who have a DQ2 isoform. This peptide, when altered by intestinal transglutaminase, has a high density of overlapping T-cell epitopes. This increases the likelihood that the DQ2 isoform will bind, and stay bound to, peptide when recognised by T-cells.[48]

Tissue transglutaminase

Tissue transglutaminase modifies gluten peptides into a form that may stimulate the immune system more effectively.[47] These peptides are modified by tTG in two ways, deamidation or transamidation.[50]

Deamidation is the reaction by which a glutamate residue is formed by cleavage of the epsilon-amino group of a glutamine side chain.[51] Transamidation is the cross-linking of a glutamine residue from the gliadin peptide to a lysine residue of tTg in a reaction that is catalysed by the transglutaminase.[50] Crosslinking may occur either within or outside the active site of the enzyme. The latter case yields a permanently covalently linked complex between the gliadin and the tTg. This results in the formation of new epitopes believed to trigger the primary immune response by which the autoantibodies against tTg develop.[52]

Stored biopsies from people with suspected coeliac disease have revealed that autoantibody deposits in the subclinical coeliacs are detected prior to clinical disease.[47]

Villous atrophy and malabsorption

The inflammatory process, mediated by T cells, leads to disruption of the structure and function of the small bowel's mucosal lining and causes malabsorption as it impairs the body's ability to absorb nutrients from food.[35][34]

Alternative causes of this tissue damage have been proposed and involve the release of interleukin 15 and activation of the innate immune system by a shorter gluten peptide (p31–43/49).[47]

Remove ads

Diagnosis

Summarize

Perspective

The diagnosis of coeliac disease is often complicated by the variety in symptoms, overlap with other disorders, and lack of awareness in medical professionals, leading to a delay in the diagnosis being made.[53][10] A diagnosis may take more than a decade after symptoms develop, and most people with coeliac disease remain undiagnosed.[11][54] Delays in diagnosis can reduce quality of life, use more medical resources and increase risk of complications associated with the disease.[53][55][56]

Coeliac disease is diagnosed based on symptoms, blood tests, and biopsies of the small intestine.[53] To make an accurate diagnosis, an individual must be consuming gluten, as the reliability of biopsies and blood tests reduces if a person is on a gluten-free diet. In those who have already reduced their gluten intake, reintroducing gluten (gluten challenge) may be required to reach an accurate diagnosis.[57] Within months of eliminating gluten from one's diet, antibodies associated with coeliac disease decrease, meaning that gluten has to be reintroduced several weeks before diagnostic testing.[57][58]

Blood tests

Current medical guidelines recommend testing tissue transglutaminase 2 immunoglobulin A (TTG IgA) in those with suspected coeliac disease.[59][60] Because IgA deficiency is more common in those with coeliac disease,[61] guidelines recommend testing for IgA deficiency as a part of the diagnostic workup for coeliac disease. If an individual with IgA deficiency is getting tested for coeliac disease, immunoglobulin G (IgG) based tests such as deamidated gliadin peptide IgG (DGP IgG) or endomysial antibody (EMA) can be used instead of IgA-based tests.[59][60] Antigliadin antibodies (AGA) and antireticulin antibodies (ARA) were historically used to test for coeliac disease, however due to the development of more accurate tests, they are no longer recommended.[7][61] Due to the risk of false positive or negative serological tests and the consequences of leaving coeliac disease untreated or introducing unnecessary dietary restrictions in the case of a false positive, biopsies are used to confirm the diagnosis regardless of blood tests.[7][60]

TG2 IgA has a high sensitivity (92.8%) and specificity (97.9%), is cost-efficient and widely available, making it the first choice for serological tests in the diagnosis of coeliac disease.[62][57] Despite this, performance of the TG2 IgA test differs between labs and no formal standardisation between assays exists.[10] The severity of small intestine damage generally correlates with the levels of TG2 IgA found in the blood, meaning that the sensitivity is lower in people who have less damage to their intestines.[62][61]

EMA has a lower sensitivity, but its specificity is near 100%.[62] Because of the high specificity, EMA can be used to confirm coeliac disease in those who have borderline TG2 IgA levels.[57] EMA testing is costly, hard to interpret and vulnerable to interobserver and inter-site variability.[10][63]

DGP IgG is used to evaluate coeliac disease in those with IgA-deficiency. Coeliac disease is more common in those with IgA-deficiency, so medical guidelines recommend that people being tested for coeliac disease are also tested for IgA-deficiency. Because IgA-based tests are unreliable in those with IgA deficiency, IgG-based tests are used instead. These include EMA IgG, DGP IgG, and TTG IgA, which are less accurate than IgA testing.[61][64]

A 2020 guideline by the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) suggests biopsy can be avoided in children who have symptoms of coeliac disease, TTG IgA levels ten times higher than normal, and a positive EMA antibody. However there is not enough evidence to suggest that a nonbiopsy approach can be used in adults.[60]

Genetic testing is not needed to diagnose coeliac disease, but is sometimes used to clarify discrepancies between blood tests and histology. In those who have already started a gluten-free diet, HLA testing can help to determine whether a gluten challenge should be performed.[60]

Endoscopy

An upper endoscopy with biopsy of the duodenum (beyond the duodenal bulb) or jejunum is performed to obtain multiple samples from the duodenum.[60] Not all areas may be equally affected; if biopsies are taken from healthy bowel tissue, the result would be a false negative. Even in the same bioptic fragment, different degrees of damage may be present.[57]

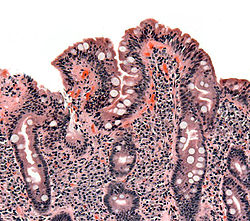

Most people with coeliac disease have a small intestine that appears to be normal on endoscopy before the biopsies are examined.[65] Endoscopic features of coeliac disease include scalloping of the small bowel folds (pictured), fissures, a mosaic pattern to the mucosa, prominence of the submucosa blood vessels, and a nodular pattern to the mucosa.[23]

Capsule endoscopy (CE) allows identification of typical mucosal changes observed in coeliac disease and may be used as an alternative to endoscopy in those who cannot or do not want one.[7]

Pathology

The Marsh-Oberhuber classification is commonly used to assess the pathological changes seen in coeliac disease.[9] Marsh originally described three different stages of coeliac disease lesions in 1992. These three stages were updated in 1999 by Oberhuber to further classify stage three.[66][67] The Marsh classification is based on three histological features: intraepithelial lymphocytes count above 25/100 enterocytes (intraepithelial lymphocytosis), elongated crypts of Lieberkuhn (crypt hyperplasia), and shortening or absence of villi (villous atrophy). As these features can be seen in other disorders, they are not diagnostic for coeliac disease without serological or clinical indications.[66] Current guidelines do not recommend a repeat biopsy unless there is no improvement in the symptoms on a gluten free diet.[58]

Gluten challenge

Currently, gluten challenge is no longer required to confirm the diagnosis in patients with intestinal lesions compatible with coeliac disease and a positive response to a gluten-free diet. A gluten challenge involves consuming over 10 grams of gluten a day for three months or until an individual tests positive for TG2 IgA.[62] Nevertheless, in some cases, a gluten challenge with a subsequent biopsy may be useful to support the diagnosis, for example, in people with positive HLA genetic testing who have negative blood antibodies and are already on a gluten-free diet.[7] Gluten challenge is discouraged before the age of 6 years and during pubertal growth.[62]

Differential diagnosis

The histopathological features associated with coeliac disease can arise from other conditions as well.[63] Differential diagnosis of negative coeliac blood tests and villous atrophy or increased inter-epithelial lymphocytes includes tropical sprue, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, lactose intolerance, lymphoma, Crohn’s disease, Helicobacter pylori, drug-induced enteropathy (azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate, olmesartan, colchicinenon, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and proton pump inhibitors), whipple disease, Giardiasis, radiation enteritis, tuberculosis, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, collagenous sprue, common variable immunodeficiency, autoimmune enteropathy, HIV enteropathy, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and gastrinoma with acid hypersecretion.[65][23][67][63] If the histological changes improve with a gluten free diet despite negative coeliac disease blood tests a diagnosis of seronegative coeliac disease may be made.[23]

Positive blood tests for coeliac disease with a lack of changes in the bowels can be caused by errors in collecting blood for the test, recent infections, congestive heart failure, chronic liver disease, and hypergammaglobulinemia. Potential coeliac disease, formerly known as "latent coeliac disease" is diagnosed when there is positive coeliac blood tests, positive HLA genetic testing, and a lack of villous atrophy.[63][7]

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is a functional disorder that causes intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms in response to gluten. The symptoms of NCGS are often similiar to those seen in coeliac disease, however they tend to have a more rapid onset and offset when compared to coeliac disease. The diagnosis of NCGS is made based on the exclusion of coeliac disease and wheat allergy, and a resolution of symptoms after adhering to a gluten free diet.[67][23]

Remove ads

Screening

Summarize

Perspective

There is debate as to the benefits of widespread screening measures for coeliac disease.[56] In 2017, the United States Preventive Services Task Force published a report found insufficient evidence to make a recommendation regarding screening for coeliac disease in those without symptoms.[68] Due to the lack of evidence that screening for coeliac disease in those without symptoms, clinical guidelines advise testing people based on symptoms and selective screening for certain populations at a higher risk of developing coeliac disease.[57][7]

Remove ads

Management

Summarize

Perspective

Currently, the only treatment for coeliac disease is a lifelong gluten-free diet (GFD). Current guidelines recommend regular follow up doctors appointments, monitoring the disease activity, preventative care and consultation with a dietitian.[53]

Diet

A GFD involves removing all food and drink which contains wheat, rye, barley and gluten derivatives.[69] Coeliac disease symptoms can improve within days of adopting a GFD and the diet improves quality of life, prevents further complications and can normalize some effects of the disease such as stunted growth.[60]

The GFD can be difficult, requiring significant education and motivation. Additionally the GFD diet may lead to nutritional deficiencies due to difficulties accessing nutritionally balanced gluten-free food.[7] As such, a referral to a dietitian is recommended by treatment guidelines.[60] A dietitian can help those with coeliac disease identify gluten containing food and maintain a nutritionally balanced diet.[7]

The exact amount of gluten which may be tolerable for those with coeliac disease varies with some people able to consume around 35 mg per day without damage to the intestines while others can not tolerate more than 10 mg a day. Currently, international regulatory agencies require a product to have less than 20 ppm (about 6mg per day) of gluten to be labelled as gluten-free.[69][23]

Monitoring

Long-term monitoring of those with coeliac disease is an important aspect of managing the disease. Usually someone newly diagnosed with coeliac disease is advised to visit their doctor multiple times a year, with follow-ups becoming less frequent (once or twice a year) after initial diagnosis. After the diagnosis, follow-up doctors appointments focus on controlling symptoms, adding in compliance to the GFD, preventative care, monitoring for comorbid diseases, and detection of complications.[60] The exact testing done depends on an individuals needs but may include a complete blood count, iron panel, thyroid testing, liver enzymes, and vitamin D levels. Due to osteoporosis being a common complication of coeliac disease, bone mineral density may be tested with a DEXA scan.[7]

Although negative anti-TG2 IgA tests do not always correlate with adherence to a GFD, guidelines recommend routine testing for anti-TG2 IgA as positive values may indicate gluten intake.[58] The role of repeat biopsies is controversial with studies finding little evidence that it is beneficial outside of investigating persistent symptoms[58][7][60]

Alongside routine vaccinations, current guidelines recommend pneumococcal vaccination due to increased risk of pneumonia in coeliac disease.[53][69]

Remove ads

Non-responsive coeliac disease

Summarize

Perspective

Around 20-40% of those with coeliac disease experience non-responsive coeliac disease (NRCD) which is the continuation of symptoms despite elimination of gluten from their diets for at least 6-12 months.[69][7]

The most common cause of NRCD is unintentional gluten ingestion, however other conditions such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, giardiasis, disaccharide or FODMAP intolerance, Crohn’s disease, fructose intolerance, microscopic colitis, pancreatic insufficiency, irritable bowel syndrome, and lactose intolerance can cause persistent symptoms or villious atrophy despite adhering to the GFD.[69][7]

Refractory coeliac disease

About 1.5% of those with coeliac disease develop refractory coeliac disease (RCD), which is the persistence of symptoms of malabsorption and villious atrophy despite at least one year of the GFD. [9][23] RCD has a high mortality and morbidity rate, is associated with more severe symptoms and is more common in older individuals (50<).[63] Those with RCD are often referred to specialists and the diagnostic process usually includes monitoring compliance with the GFD, confirming the initial diagnoses of coeliac disease, and excluding alternative explanations for small intestine damage such as Crohn’s disease, peptic duodenitis, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, hypogammaglobulinemia, common variable immunodeficiency, autoimmune enteropathy, tropical sprue, collagenous sprue, and eosinophilic enteritis.[63][7]

There are two subtypes of RCD, type 1 and type 2. Biopsies of the duodenum and analysis of the intraepithelial lymphocytes in the duodenum are required to distinguish between the two types.[63][9] Type 2 RCD is characterized by abnormal T cells in the small intestine, these findings are absent in type 1 RCD.[7] In type 2 RCD, healthy lymphocytes are replaced by abnormal lymphocytes, increasing the risk of complications such as enteropathy-associated T- cell lymphoma (EATL), severe malabsorption, and ulcerative jejunoileitis, and results in poorer outcomes.[63][7]

Type 1 RCD is treated with steroids, azathioprine, and budesonide. The treatment of type 2 RCD is more complicated as it often does not improve with steroids and azathioprine may increase the risk of EATL. Proposed treatment of type 2 RCD includes cladribine, cyclosporine, and stem cell transplants.[23][9]

Remove ads

Epidemiology

Summarize

Perspective

In most countries, between 1 in 50 and 1 in 200 people have coeliac disease.[70] Rates vary in different regions of the world; coeliac disease is less common in places where gluten-containing crops are rarely eaten, and in parts of east Asia and sub-Saharan Africa where populations rarely carry the HLA-DQ genes that predispose to the disease.[70] The risk of developing coeliac disease is higher in those who have a first degree relative with the disease, a less dramatic increase in risk is also seen second degree relatives.[71]

Diagnoses of coeliac disease have increased dramatically in recent decades due to increased awareness of the disease and availability of blood testing. However, the disease is still thought to be underdiagnosed, with an estimated 70% of people with coeliac undiagnosed and untreated. Undiagnosed cases are more common in poorer areas, and in countries which do not regularly test at-risk people.[70]

While coeliac disease can arise at any age, most people develop the disease before age 10.[72] Roughly 20 percent of individuals with coeliac disease are diagnosed after 60 years of age.[73] Coeliac disease is slightly more common in women than in men; though some of that may be due to differences in diagnostic practice – men with gastrointestinal symptoms are less likely to receive a biopsy than women.[72] Other populations at increased risk for coeliac disease, include individuals with Down and Turner syndromes, type 1 diabetes, and autoimmune thyroid disease, including both hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) and hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid).[67]

History

Summarize

Perspective

The term coeliac comes from Greek κοιλιακός (koiliakós) 'abdominal' and was introduced in the 19th century in a translation of what is generally regarded as an Ancient Greek description of the disease by Aretaeus of Cappadocia.[74][75]

Humans first started to cultivate grains in the Neolithic period (beginning about 9500 BCE) in the Fertile Crescent in Western Asia, and, likely, coeliac disease did not occur before this time.[76] Aretaeus of Cappadocia, living in the second century in the same area, recorded a malabsorptive syndrome with chronic diarrhoea, causing a debilitation of the whole body.[74]

A 15th-century medical prescription from Mamluk Cairo, attributed to Shams al-Din ibn al-'Afif, the personal physician to Sultan Barsbay and director of the Qalawun complex hospital, describes a treatment for symptoms consistent with coeliac disease. Found in Fustat and now held in the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo, the remedy combines herbs and plant waters for patients intolerant to wheat.[77]

Aretaeus of Cappadocia's "Cœliac Affection" gained the attention of Western medicine when Francis Adams presented a translation of Aretaeus's work at the Sydenham Society in 1856. The patient described in Aretaeus' work had stomach pain and was atrophied, pale, feeble, and incapable of work. The diarrhoea manifested as loose stools that were white, malodorous, and flatulent, and the disease was intractable and liable to periodic return. The problem, Aretaeus believed, was a lack of heat in the stomach necessary to digest the food and a reduced ability to distribute the digestive products throughout the body, this incomplete digestion resulting in diarrhoea. He regarded this as an affliction of the old and more commonly affecting women, explicitly excluding children. The cause, according to Aretaeus, was sometimes either another chronic disease or even consuming "a copious draught of cold water."[74][75]

The paediatrician Samuel Gee gave the first modern-day description of the condition in children in a lecture at the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London, in 1887. Gee acknowledged earlier descriptions and terms for the disease and adopted the same term as Aretaeus (coeliac disease). He perceptively stated: "If the patient can be cured at all, it must be by means of diet." Gee recognised that milk intolerance is a problem with coeliac children and that highly starched foods should be avoided. However, he forbade rice, sago, fruit, and vegetables, which all would have been safe to eat, and he recommended raw meat as well as thin slices of toasted bread. Gee highlighted particular success with a child "who was fed upon a quart of the best Dutch mussels daily." However, the child could not bear this diet for more than one season.[75][78]

Christian Archibald Herter, an American physician, wrote a book in 1908 on children with coeliac disease, which he called "intestinal infantilism". He noted their growth was retarded and that fat was better tolerated than carbohydrate. The eponym Gee-Herter disease was sometimes used to acknowledge both contributions.[79][80] Sidney V. Haas, an American paediatrician, reported positive effects of a diet of bananas in 1924.[81] This diet remained in vogue until the actual cause of coeliac disease was determined.[75]

While a role for carbohydrates had been suspected, the link with wheat was not made until the 1940s by the Dutch paediatrician Willem Karel Dicke.[82] It is likely that clinical improvement of his patients during the Dutch famine of 1944–1945 (during which flour was scarce) may have contributed to his discovery.[83] Dicke noticed that the shortage of bread led to a significant drop in the death rate among children affected by coeliac disease from greater than 35% to essentially zero. He also reported that once wheat was again available after the conflict, the mortality rate soared to previous levels.[84] The link with the gluten component of wheat was made in 1952 by a team from Birmingham, England.[85] Villous atrophy was described by British physician John W. Paulley in 1954 on samples taken at surgery.[86] This paved the way for biopsy samples taken by endoscopy.[75]

Throughout the 1960s, other features of coeliac disease were elucidated. Its hereditary character was recognised in 1965.[87] In 1966, dermatitis herpetiformis was linked to gluten sensitivity.[75][88]

Remove ads

Society and culture

Summarize

Perspective

May has been designated as "Coeliac Awareness Month" by several coeliac organisations.[89][90]

Christian churches and the Eucharist

Speaking generally, the various denominations of Christians celebrate a Eucharist in which a wafer or small piece of sacramental bread from wheat bread is blessed and then eaten. A typical wafer weighs about half a gram.[91] Small communion wafers typically contain 2-5 mg of gliadin if they are not a gluten-free variety,[92] and many people with coeliac disease report altering their religious practices because of coeliac symptoms caused by these wafers.[93]

Many Christian churches offer their communicants gluten-free alternatives, usually in the form of a rice-based cracker or gluten-free bread. These include the United Methodist, Christian Reformed, Episcopal, Anglican and Lutheran Churches. Catholics may receive from the chalice alone, or ask for gluten-reduced hosts; gluten-free ones however are not considered still to be wheat bread, and hence are invalid matter.[94]

Roman Catholic position

Roman Catholic doctrine states that for a valid Eucharist, the bread to be used at Mass must be made from wheat. Low-gluten hosts meet all of the Catholic Church's requirements, but they are not entirely gluten-free. Requests to use rice wafers have been denied.[95] In 2003, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith stated, "Given the centrality of the celebration of the Eucharist in the life of a priest, one must proceed with great caution before admitting to Holy Orders those candidates unable to ingest gluten or alcohol without serious harm."[96]

By 2004, extremely low-gluten Church-approved hosts had become available in the United States, Italy and Australia.[97] As of 2017, the Vatican still outlawed the use of gluten-free bread for Holy Communion.[98]

Passover

The Jewish festival of Pesach (Passover) may present problems with its obligation to eat Matzah, which is unleavened bread made in a strictly controlled manner from wheat, barley, spelt, oats, or rye. In addition, many other grains that are normally used as substitutes for people with gluten sensitivity, including rice, are avoided altogether on Passover by Ashkenazi Jews. Many kosher-for-Passover products avoid grains altogether and are therefore gluten-free. Potato starch is the primary starch used to replace the grains.[99]

Remove ads

Research directions

Summarize

Perspective

Research in the diagnosis of coeliac disease has been aimed at developing new blood tests, including tests that could be used for those are not currently eating gluten. These tests measure certain immune cells that react to gluten, such as CD4+ T cells and HLA-DQ-gluten tetramers.[62][100][101]

Technological advances aimed at improving adherence to the GFD have been developed in recent years. Food sensors such as the Nima sensor, could allow people to measure how much gluten is in food to prevent accidental gluten consumption. Testing kits that measure gluten levels in urine and waste may help measure adherence the GFD.[102]

There has been many different proposed strategies to develop further treatments for coeliac disease. Altering wheat to be safer for those with coeliac disease has been explored using methods such as genetic manipulation of wheat and using a chemical process (transamidation) that changes gluten proteins so they no longer trigger an immune reaction.[100][103] Medications and techniques such as chitosan and AGY gluten sequestering aim to prevent gluten from interacting with the immune system.[100] Glutenases are enzymes taken with food designed to help break down and neutralize gluten in the intestines. Glutenases currently being studied include latiglutenase–ALV003, Aspergillus niger prolyl endoprotease, Kuma030–TAK-062, and endoproptease-40.[103][7]

Larazotide acetate is a peptide that helps tighten the junctions between intestinal cells, reducing intestinal permeability. It helps decrease reactions to gluten by preventing gluten fragments from passing through the gut lining and triggering the immune system.[7]

Treatments focused on immunomodulation aim to target the T cells that react to gluten and reduce intolerance to gluten.[103]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads