Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Charlotte's Web

1952 children's novel by E. B. White From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

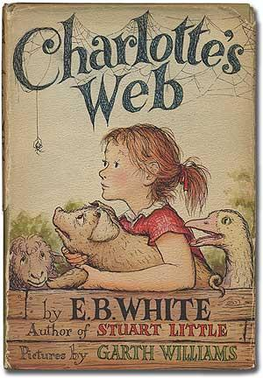

Charlotte's Web is a book of children's literature by American author E. B. White and illustrated by Garth Williams. It was published on October 15, 1952, by Harper & Brothers. It tells the story of a livestock pig named Wilbur and his friendship with a barn spider named Charlotte. When Wilbur is in danger of being slaughtered, Charlotte writes messages in her web praising him, such as "Some Pig", "Terrific", "Radiant", and "Humble", to persuade the farmer to spare his life.

The book is considered a classic of children's literature, enjoyed by readers of all ages.[1] The description of the experience of swinging on a rope swing at the farm is an often-cited example of rhythm in writing, as the pace of the sentences reflects the motion of the swing. In 2000, Publishers Weekly listed the book as the best-selling children's paperback of all time.[2]

The book was adapted into an animated feature film produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions and Sagittarius Productions and distributed by Paramount Pictures in 1973. In 2003, the company released a direct-to-video sequel, Charlotte's Web 2: Wilbur's Great Adventure; Universal released the film internationally.[3] A live-action feature film adaptation of the book was released in 2006. A video game based on this adaptation was released that same year. A three-episode miniseries produced by Sesame Workshop and Guru Studio was released on HBO Max on October 2, 2025.

Remove ads

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

The Arable family are a farm family who raise and sell animals. One day, John Arable attempts to slaughter the runt of a litter of 11 piglets that were born the night before, but his daughter Fern pleads for the piglet's life, and John gives him to her. Naming him Wilbur, Fern treats him as a pet, and the two become incredibly close. Eventually, Wilbur is no longer small, and so John decides to sell him, to Fern's dismay. Wilbur is given to Fern's maternal uncle-by-marriage, Homer Zuckerman, allowing her to periodically visit him.

From here on, the various farm animals are depicted as anthropomorphic. In Zuckerman's barnyard, Wilbur yearns for Fern and is met with varying reactions from the other animals, with some, such as the motherly goose, showing him compassion, and others, such as the head ram, treating him with scorn. One day, the ram offhandedly tells Wilbur that Zuckerman is raising him for slaughter and consumption, leaving him distraught. As he mourns his fate, a barn spider named Charlotte, whose web sits in a doorway overlooking his pigpen, comforts him. She promises to find a way to save his life and takes on a motherly role for him. Meanwhile, Fern often listens in on the animals' conversations, to her mother's concern.

As summer passes, Charlotte comes up with a plan to save Wilbur. Reasoning that Zuckerman would not kill a famous pig, she weaves words and short phrases in praise of Wilbur into her web, the first phrase being "Some Pig". This turns Wilbur, and the barn as a whole, into a tourist attraction because many people believe the web to be a miracle. After the excitement dies down, the phrase gets destroyed. On the goose's suggestion, Charlotte weaves the word "Terrific" into her web, beginning the cycle anew. Although Zuckerman is pleased with Wilbur's fame, his plan to slaughter him stays firm. In another effort to maintain the public's interest in him, Charlotte tells Templeton, a gluttonous rat that lives under Wilbur's trough and holds a contentious relationship with the other animals, to get another word for the web. Templeton finds a laundry detergent ad with the word "Radiant", which Charlotte then weaves into her web.

As a result of this latest round of fame, Zuckerman enters Wilbur in the county fair, and Charlotte and Templeton accompany him. The Arables also go to the fair, but Fern, despite still cherishing Wilbur, has matured, and instead spends time with her childhood sweetheart, Henry Fussy. Charlotte weaves another word brought by Templeton, "Humble", into the web she spins at Wilbur's stall at the fair. Wilbur fails to win first prize, but is awarded a special prize by the judges. Charlotte, who has laid an egg sac at the fair, hears the presentation of the award over the public address system and realizes that the prize means Zuckerman will cherish Wilbur for as long as he lives and will never slaughter him. However, Charlotte, being a barn spider with a naturally short lifespan, is already dying of natural causes by the time the award is announced. Knowing that she has saved Wilbur, and satisfied with the outcome of her life, she decides not to return to the barn with Wilbur and Templeton. She gives them her final request to have her egg sac taken back to the barn, and then dies alone at the fairgrounds.

Wilbur waits out the winter, during which Charlotte's children hatch. Most of them fly away, to Wilbur's dismay, but three choose to remain. Future descendants of Charlotte keep Wilbur company for many years, though he always holds Charlotte in more esteem than them all.

Remove ads

Characters

- Wilbur is a rambunctious pig, the runt of his litter. He is often strongly emotional.

- Charlotte A. Cavatica, or simply Charlotte, is a spider who befriends Wilbur. In some passages, she is the heroine of the story.[4]

- John Arable is Wilbur's first owner.

- Fern Arable is John's daughter who adopts Wilbur when he's a piglet and later visits him. She is the only human in the story capable of understanding animal conversation.

- Lurvy is the hired man at Zuckerman's farm and the first to read the message in Charlotte's web.

- Templeton is a rat who helps Charlotte and Wilbur only when offered food. He serves as a somewhat caustic, self-serving comic relief to the plot.

- Avery Arable is Fern's elder brother and John's son. Like Templeton, he is a source of comic relief.

- Homer Zuckerman is Fern's uncle who keeps Wilbur in his barn. He has a wife named Edith and an assistant named Lurvy.

- Other animals in Zuckerman's barn, with whom Wilbur converses, include a disdainful lamb, a talkative goose, and an intelligent "old sheep".

- Henry Fussy is a boy of Fern's age, of whom Fern becomes fond.

- Dr. Dorian is the family physician/psychologist consulted by Fern's mother and something of a wise old man character.

- Uncle is a large pig whom Charlotte disdains for his coarse manners but is recognized as Wilbur's rival at the fair.

- Charlotte's children are the 514 children of Charlotte the spider. Although they were born at the barn, all but three of them (Joy, Aranea, and Nellie) go their own ways by ballooning.

Remove ads

Themes

Summarize

Perspective

Death

Death is a major theme seen throughout the book and is brought forth by that of Charlotte. According to Norton D. Kinghorn, Charlotte's web acts as a barrier that separates the two worlds of life and death.[5] Scholar Amy Ratelle says that through Charlotte's continual killing and eating of flies throughout the book, White makes the concept of death normal for Wilbur and the readers.[6] Neither Wilbur nor Templeton sees death as a part of their lives; Templeton sees it only as something that will happen at some time in the distant future, while Wilbur views it as the end of everything.[7]

Wilbur constantly has death on his mind at night when he is worrying over whether or not he will be slaughtered.[8] Even though he is able to escape his death, Charlotte, who takes care of him, is not able to escape her own. She passes away, but, according to Trudelle H. Thomas, "even in the face of death, life continues and ultimate goodness wins out".[9] Jordan Anne Deveraux explains that E.B. White discusses a few realities of death. From the novel, readers learn that death can be delayed but that no one can avoid it forever.[10]

Change

For Norton D. Kinghorn, Charlotte's web also acts as a signifier of change. The change Kinghorn refers to is that of both the human world and the farm/barn world. For both of these worlds, change is something that can't be avoided.[5] Along with the changing of the seasons throughout the book, the characters also go through their own changes. Jordan Anne Deveraux also explains that Wilbur and Fern each go through their changes to transition from childhood closer to adulthood throughout the novel.[10] This is evidenced by Wilbur accepting death and Fern giving up her dolls. Wilbur grows throughout the book, allowing him to become the caretaker of Charlotte's children just as she was a caretaker for him, as is explained by scholar Sue Misheff.[11] But rather than accept the changes that are forced upon them, according to Sophie Mills, the characters aim to go beyond the limits of change.[8] In a different way, Wilbur goes through a change when he switches locations. Amy Ratelle explains that when he moves from the Arables' farm to Homer Zuckerman's farm, he goes from being a loved pet to a farm animal.

Innocence

Fern goes from being a child to being more of an adult. As she experiences this change, Kinghorn notes that it can also be considered a fall from innocence.[5] Wilbur also starts out young and innocent at the beginning of the book. A comparison is drawn between the innocence and youth of Fern and Wilbur. Sophie Mills states that they can identify with one another.[8] Both Wilbur and Fern are, at first, horrified by the realization that life must end; however, by the end of the book, they learn to accept that, eventually, everything must die.[10] According to Matthew Scully, the book presents the difference in the worldview of adults versus the worldview of children. Children, such as Fern, believe killing another for food is wrong, while adults have been gradually conditioned to believe that it is natural.[12]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The book was published three years after White began writing it.[13] His editor, Ursula Nordstrom, said that one day in 1952, he arrived at her office and handed her a new manuscript, the only copy of the book then in existence, which she read soon after and enjoyed.[14] The book was released on October 15, 1952.[15][16][17]

In light of White's Death of a Pig, published in 1948,[18] which gives an account of his own failure to save a sick pig (bought for butchering), the book can be seen as his attempt "to save his pig in retrospect".[19] His overall motivation for the book has not been revealed, and he once wrote: "I haven't told why I wrote the book, but I haven't told you why I sneeze, either. A book is a sneeze."[20]

Dear Vladimir:

There is a large grey spider that commonly inhabits out-buildings and sheds, and I turn to you on the chance that you know her and can enlighten me as to certain of her more intimate habits and functions—this because she figures in a book I am writing and I find myself, at this point, stuck....

—E. B. White, October 8, 1950[21]

White encountered the spider at his farm in Hancock County, Maine in October 1950. Unable to identify it himself, he asked his friend Vladimir Nabokov, the novelist and lepidopterist, for advice. Nabokov replied that he knew "nothing at all" about spiders, but suggested that White contact Willis J. Gertsch at the American Museum of Natural History.[21] Gertsch's book American Spiders was one of the sources for the arachnid anatomical terms (mentioned in the beginning of chapter nine), along with The Spider Book by John Henry Comstock, both of which combine a sense of poetry with scientific fact.[22] White incorporated details from Comstock's accounts of baby spiders, most notably the "flight" of the young spiders on silken parachutes.[22]

He sent Gertsch's book to illustrator Garth Williams.[23] Williams's initial drawings depicted a spider with a woman's face, and White suggested that he simply draw a realistic spider instead.[24]

White's original name for the novel's spider character was Charlotte Epeira (after Epeira sclopetaria, the Grey Cross spider, now known as Larinioides sclopetarius), before discovering that the more modern name for that genus was Aranea.[25] In the book, Charlotte gives her full name as "Charlotte A. Cavatica", revealing her as a barn spider, an orb-weaver with the scientific name Araneus cavaticus.[citation needed]

White originally opened the book with an introduction of Wilbur and the barnyard (which later became the third chapter) but decided to begin the book by introducing Fern and her family on the first page.[23] White's publishers were at one point concerned with the end and tried to get him to change it.[26]

Charlotte's Web has become White's most famous book, but he treasured his privacy and that of the farmyard and barn that helped inspire it, which have been kept off limits to the public according to his wishes.[27]

Remove ads

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

The book was generally well-reviewed when it was released. In The New York Times, Eudora Welty wrote: "As a piece of work it is just about perfect, and just about magical in the way it is done."[28]

Aside from its paperback sales, the book is 78th on the all-time bestselling hardback book list. According to publicity for the 2006 film adaptation (see below), it has sold more than 45 million copies and been translated into 23 languages. It was a Newbery Honor book for 1953, losing to Secret of the Andes by Ann Nolan Clark for the medal.[29][30]

In 1970, White won the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal, a major prize in the field of children's literature, for Charlotte's Web along with his first children's book, Stuart Little (1945).[31]

Seth Lerer, in his book Children's Literature, finds that Charlotte represents female authorship and creativity, and compares her to other female characters in children's literature such as Jo March in Little Women and Mary Lennox in The Secret Garden.[32] Nancy Larrick brings to attention the "startling note of realism" in the opening line, "Where's Papa going with that ax?"[33]

Illustrator Henry Cole expressed his deep childhood appreciation of the characters and story, and calls Garth Williams's illustrations full of "sensitivity, warmth, humor, and intelligence".[34] Illustrator Diana Cain Bluthenthal states that Williams' illustrations inspired and influenced her.[35]

An unabridged audio book read by White himself reappeared decades after it had originally been recorded.[36] Newsweek writes that White reads the story "without artifice and with a mellow charm", and that "White also has a plangency that will make you weep, so don't listen (at least, not to the sad parts) while driving".[36] Joe Berk, president of Pathway Sound, had recorded the book with White in his neighbor's house in Maine (which Berk describes as an especially memorable experience) and released it in LP.[37] From Michael Sims: "The producer later said that it took him 17 takes to read the death scene of Charlotte. And finally, they would walk outside, and E.B. White would go, this is ridiculous, a grown man crying over the death of an imaginary insect. And then, he would go in and start crying again when he got to that moment."[38] Bantam released Charlotte's Web alongside Stuart Little on CD in 1991, digitally remastered, having acquired the two books for rather a large amount.[37]

In 2005, a teacher in California conceived of a project for her class in which they would send out hundreds of drawings of spiders (each representing Charlotte's child, Aranea, going out into the world so that she can return and tell Wilbur of what she has seen) with accompanying letters; they ended up visiting a large number of parks, monuments, and museums, and were hosted by or prompted responses from celebrities and politicians such as John Travolta and then-First Lady Laura Bush.[39]

In 2003, the book was listed at number 170 on the BBC's The Big Read poll of the UK's 200 "best-loved novels".[40] A 2004 study found that it was a common read-aloud book for third-graders in schools in San Diego County, California.[41] Based on a 2007 online poll, the National Education Association listed it as one of its "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children."[42] It was one of the "Top 100 Chapter Books" of all time in a 2012 poll by School Library Journal.[43]

In 2010, the New York Public Library reported that Charlotte's Web was the sixth most borrowed book in its history.[44]

Its awards and nominations include:

- John Newbery Honor Book (1953)[45]

- Horn Book Fanfare (1952)[46]

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal (1970) (awarded to White for his children's books: Charlotte's Web and Stuart Little)

- Massachusetts Children's Book Award (1984)[47]

Remove ads

Adaptations

Summarize

Perspective

Film

The book was adapted into an animated feature of the same name in 1973[48] by Hanna-Barbera Productions and Sagittarius Productions and released by Paramount Pictures with a score by the Sherman Brothers. This film was followed on March 18, 2003 by a direct-to-video sequel, Charlotte's Web 2: Wilbur's Great Adventure, that was released by Paramount Home Entertainment and Universal Home Entertainment Productions, with Nickelodeon Animation Studio providing animation services.

A live-action film adaptation of the book, produced by Paramount Pictures, Walden Media, Kerner Entertainment Company, and Nickelodeon Movies, was released on December 15, 2006. It starred Dakota Fanning as Fern and Julia Roberts as the voice of Charlotte.

Miniseries

On March 8, 2022, it was announced that Sesame Workshop was working on an animated miniseries based on the book.[49] It was in production for a few months, and was slated to premiere in 2024 on Cartoon Network and HBO Max.[50] On November 3, 2022, it was reported that the miniseries would not be moving forward.[51] However, Canadian animation studio Guru Studio claimed it is still in production.[52] The miniseries was released on HBO Max on October 2, 2025.[53] Narrated by Jean Smart, it features the voices of Amy Adams as Charlotte, Elijah Wood as Adult Wilbur, Griffin Robert Faulkner as Wilbur, Cynthia Erivo as Goose, Natalie Chan as Fern, Danny Trejo as Gander, Randall Park as Templeton, Chris Diamantopoulos as Homer, Rosario Dawson as Edith, Ana Ortiz as Dolores, Tom Everett Scott as John, Leith Burke as George, Keith David as Old Sheep and Patricia Richardson as Widow Fussy with Dee Bradley Baker voicing various animals.[54]

Stage

A musical production was created with music and lyrics by Charles Strouse.[55]

Video game

A video game of the 2006 film was developed by Backbone Entertainment and published by THQ and Sega, and released on December 12, 2006, for the Game Boy Advance, Nintendo DS and PC.[56] A separate game also based on the film was released a year later for the PlayStation 2 developed by Blast! Entertainment.

Ebook

On March 17, 2015, HarperCollins Children's Books released an ebook version.[57]

Audio Drama

Radio Times Issue 3701[58] reports the Children's Radio 4 broadcast the abridged reading by William Hootkins of Charlotte's Web across two days 19 March 1994 and 20 March 1994 at 10:30 each day.

Radio Times Issue 4225[59], reports the BBC Radio 4 FM Afternoon Play first broadcasting of Charlotte's Web in two parts on 22 March 2005 and 23 March 2005 at 14:15 each day. The cast indluded:

- Dominic Cooper as Wilbur

- Sophie Thompson as Charlotte

- Ken Campbell as Templeton

- Angela Curran as Old Sheep

- Colleen Prendergast as Goose

- Dominic Curran as Little Lamb and Goslings

- Kerry Shale as Lurvy

- John Chancer as Homer Zuckerman

- Laurence Bouvard as Edith

- Laurel Lefkow as Mrs Martha Arable

- Georgina Hagan as Fern

- Corbyn Thomas Smith as Avery

- Peter Marinker as the Narrator and John Arable

The broadcast was adapted for radio by the Director, Chris Wallis and was based on the play by Joseph Robinette.

Remove ads

See also

References

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads