Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Clarion–Clipperton zone

Fracture zone of the Pacific Ocean seabed From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

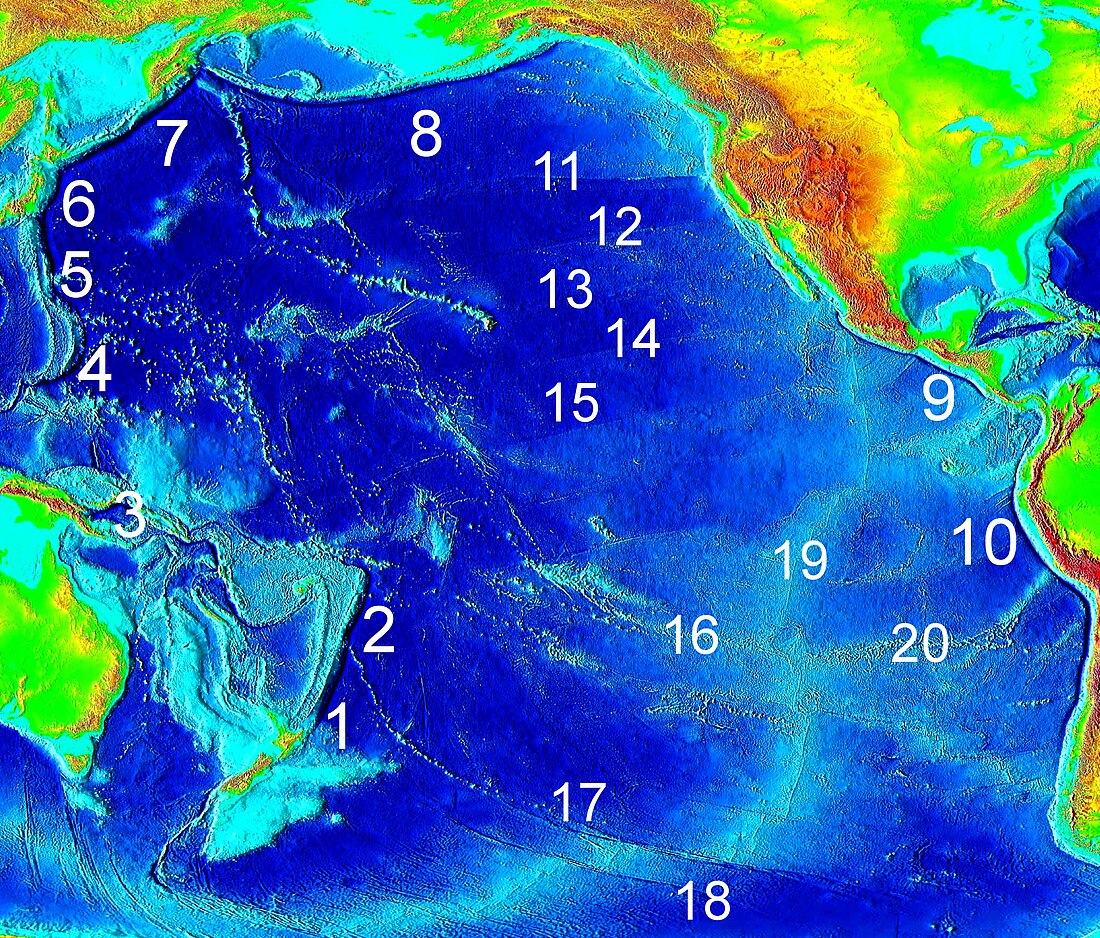

The Clarion–Clipperton zone[1] (CCZ) or Clarion–Clipperton fracture zone[2] is an environmental management area of the eastern and central Pacific Ocean, lying between Hawaii and Mexico. It is one of the world's largest known fields of polymetallic nodules and is administered by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).[3] The region includes the Clarion fracture zone and the Clipperton fracture zone, geological submarine fracture zones. Clarion and Clipperton are two of the five major lineations of the northern Pacific floor, and they were discovered by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1954.[4]

The CCZ extends around 4,500 miles (7,240 km) East to West[5] and spans approximately 4,500,000 square kilometres (1,700,000 sq mi).[6] The fractures themselves are unusually mountainous topographical features. Depths across the CCZ generally range from 4,000 to 6,000 metres (9,800 to 19,700 ft).[7]

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is regularly considered for deep-sea mining due to the rich deposits of manganese, nickel, copper, and cobalt.[8] Scientific surveys, however, have found the CCZ contain an abundance and diversity of life – more than half of the species collected were new to science.[9] These findings have led to significant environmental and governance debates, particularly centering ISA permits regarding mining regulations, like the operation of the "two-year rule," and international calls for a precautionary pause or moratorium on commercial seabed mining.[4]

Remove ads

Etymology

The Clarion fracture zone is named after Clarion Island a volcanic island in the Revillagigedo Archipelago west of Mexico. Similarly, the Clipperton fracture zone is named after Clipperton Island located along the same latitude as the feature.[10]

The combined term "Clarion-Clipperton Zone" was later adopted by the International Seabed Authority to represent the larger environmental regulated region that includes both the fracture zones and surrounding abyssal plain.[4]

Remove ads

Geography

Summarize

Perspective

The fractures can be divided into four parts:

- The first, 127°–113° W, is a broad, low welt of some 900 miles (1,400 km), with a central trough 10 to 30 miles (16 to 48 km) wide;

- The second, 113°-107° W, is a volcano enriched ridge, 60 miles (97 km) wide and 330 miles (530 km) long;

- The third, 107°-101° W, is a low welt with a central trough 1,200–2,400 feet (370–730 m) deep which transects the Albatross Plateau; and

- The fourth, 101°-96° W, contains the Tehuantepec Ridge which extends 400 miles (640 km) northeast to the continental margin.[10]

The Nova-Canton Trough is often seen as an extension of the fractures.[11]

The underlying crust in the CCZ consists mainly of Mid-Eocene to Early Miocene basaltic seafloor, forming extensive abyssal hills and plains. The seafloor is capped by a sequence of deep-sea sediments.[12] With the thick layers of Mid-Eocene at the bottom, there are recent chalks (the Marquesas Oceanic Formation) and siliceous clay-ooze (the Clipperton Formation) that may reach 20-30 metres thick.[12] Local geomorphology includes knoll seamounts, potholes formed in chalk units, and mobile sediment drifts. Together, the seabed captures a diverse microhabitat, and the region's geological heterogeneity is thought to contribute to variations in benthic biodiversity and ecosystem structure.[12]

The zone contains nodules made up of valuable rare-earth and other minerals. Some of these play an essential role for the energy transition to a low carbon economy.[13] These nodules form around bone fragments or shark teeth. Micronodules then further aggregate and accrete into the clumps targeted for harvesting.[14]

Clipperton fracture zone

The Clipperton fracture zone is the southernmost of the north east Pacific Ocean lineations. It begins east-northeast of the Line Islands and ends in the Middle America Trench off the coast of Central America,[5][15][10] forming a rough line on the same latitude as Kiribati and Clipperton Island, from which it gets its name.

Clarion fracture zone

The Clarion fracture zone is the next Pacific lineation north of Clipperton FZ. It is bordered on the northeast by Clarion Island, the westernmost of the Revillagigedo Islands, from which it gets its name. Both fracture zones were discovered by the U.S. research vessels "Horizon" and "Spencer F. Baird" in 1954.[16]

Remove ads

Deep sea mining

Summarize

Perspective

The Clarion–Clipperton Zone lies within “the Area,” meaning the portions of seabed beyond national jurisdiction, as defined under the United Nation Convention on the Law of Sea (UNCLOS).[4] The Area is legally designated as the Common Heritage of Mankind (CHM), proposed by Arvid Pardo in 1967, and mineral explorations in the CCZ are under the regulation of the International Seabed Authority.[4] Governance of the CCZ emerged from late twentieth-century debates on deep-sea resource rights, specifically discussions comparing treatment of seabed and economic exclusive zone (EEZ).[4]

Since the 2000s, large areas of the CCZ have been surveyed for mineral and environmental assessments. 173,000 km² of the region has been mapped in seven regions associated with the NORI, TOML, and Marawa exploration contract areas.[12] These mapped zones span roughly 2,000 km longitudinally (116°–134.5° W) and 700 km latitudinally (10°–16° N). The ISA has also designated thirteen Areas of Particular Environmental Interest (APEIs) intended to preserve representative ecosystems across the CCZ.[17] However, some biodiversity surveys indicate that many known species have been observed exclusively outside of APEIs, raising debates regarding their representativeness.[18] Approximately 1,000,000 square kilometres (390,000 sq mi) of the region has been claimed by 16 mining regions.[1] A further nine areas, each covering 160,000 square kilometres (62,000 sq mi), have been set aside for conservation.[1]

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) estimates that the total amount of polymetallic nodules in the Clarion–Clipperton zone exceeds 21 billion tons (Bt), containing about 5.95 Bt of manganese, 0.27 Bt of nickel, 0.23 Bt of copper and 0.05 Bt of cobalt.[7] Geochemical surveys show that nodule composition varies significantly across the region: Mn/Fe ratios, Ni and Cu content, and Co/Ni patterns differ between eastern and western sub-domains.[8] These differences have been linked to variations in sedimentation rate, bottom-water oxygenation, and the relative contributions of hydrogenetic and diagenetic formation processes.[8] The nodules are generally cultivated within the geochemically active interface, below the calcite lysocline, where chalk strata are overlain by mobile siliceous clay-ooze. Acoustic surveys show higher than average seabed backscatter in zones with larger and more abundant nodules. The ISA has issued 19 licences for mining exploration within this area.[19] Exploratory full-scale extraction operations were set to begin in late 2021.[20] ISA aimed to publish the deep sea mining code in July 2023. Commercial license applications were to be accepted for review thereafter.[21] By 2021, the ISA has granted 18 exploration contracts.[22]

Seabed mining at CCZ often involves seafloor collector vehicles that use riser pipes to extract nodules systematically to the surface. These operations typically generate two types of sediment plumes.[23] Vehicle movement approximate to the seafloor will create near-bottom collector plumes, and the extraction process will cause mid-water discharge plumes.[23] A field experiment done by Scripps Institution of Oceanography has shown that discharge plumes become rapidly diluted but consist of fine particles capable of long-distance transport, and subsequently built a model to inform environmental guidelines regarding potential damage from sediment plumes.[23] Considering sediment plumes being one of the main pathways for potential environmental harm in seabed mining, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) is actively developing science-based discharge thresholds to regulate plume concentration, spatial scales and duration through operational limits, real-time monitoring, and precautionary thresholds.[24]

The so-called two-year rule states that before regulations are passed, a member nation has the authority to notify ISA that it wants to mine. This starts a two-year clock during which the ISA can come up with rules. If it fails to do so, the mining is implicitly approved. Nauru gave notice in July 2021, creating a deadline of July 9, 2023. ISA's next meeting, however, begins a day later, on July 10.[14]

Remove ads

Biodiversity in the CCZ

Summarize

Perspective

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) is habitat to diverse marine wildlife. More than 400 described species are recorded and 42% of known deep-sea species were first discovered in CCZ.[17] Yet, environmental assessments have highlighted that biodiversity in the CCZ remains incompletely characterized.[17] Surveys have suggested that 88-92% benthic metazoan species may remain undescribed, and Rarefaction curves show that sampling is not yet saturated, with each new survey tending to record extra discoveries.[17] In addition, a large proportion of species in the CCZ are known from a single record, implying the proportion of unexplored biodiversity.[17]

Researchers have begun to refine this picture at smaller spatial scales. One survey of a single 30 x 30 km study box in the UK-1 exploration area documented 42 mollusc records representing 21 species, including one described new species and more than twelve potentially undescribed taxa.[18] The discovered genetic pull is found to have no genetic matches in public reference databases, and the authors also showed that several morphologically similar molluscs are genetically distinct.[18] In contrast to previously held apparent cosmopolitan distributions based on morphology alone, this research suggests that a high degree of endemism might exist in the CCZ.[18]

One species that inhabits the fracture zone are xenophyophores. A 2017 study found 34 novel species in the area. Xenophyophores are highly sensitive to human disturbances, such that mining may adversely affect them. They play a keystone role in benthic ecosystems such that their removal could amplify ecological consequences.[25] The nodules are considered "critical for food web integrity".[26] The zone hosts corals, sea cucumbers, worms, dumbo octopuses and many other species.[27]

Along with the xenophyophores, many types of species reside in the Clarion–Clipperton zone: protists, microbial prokaryotes, and various fauna including megafauna, macrofauna, and meiofauna, each distinguished by size.[28] Due to the lack of historical research in the region—in large part because of the inaccessibility, monetary, and physical cost without modern technology—very little is known about life in the CCZ. The increasing tests in the region have led to the discovery of many new species, suggesting both a high species richness and high species rarity within the CCZ. It seems that polymetallic nodules in the region, the target of much deep-sea mining, are crucial for fostering a high level of biodiversity on the sea floor. Even so, there are many gaps in the current understanding of the ecosystem roles played, life history traits, sensitivities, spatial or temporal variabilities, and resilience of these species.[29]

Some studies have suggested that polymetallic nodules form "nodule provinces" that provide distinctive hard-substrate habitat in an otherwise sediment-dominated abyssal plain.[4] Studies have shown abundant infaunal species such as Nucula profundorum inhabit in these soft sediments, as well as nodule-attached molluscs and other epifauna, indicating that nodules add structural complexity and increase the diversity of available microhabitats at the seafloor.[18] Geological heterogeneity has been proposed as another important driver of biodiversity in the CCZ.[30] The region contains abyssal hills, knolls, potholes, seamounts, sediment drifts and nodule-rich plains, accompanied with layers of chalk and clay-ooze formations.[12] Researchers note that sediment type, relief, or bedrock exposure may play a vital rule in the composition of benthic communities, and habitat diversity and resource distribution may be more closely linked than previously thought.[7]

Remove ads

Environmental concerns

Summarize

Perspective

Researchers associated with International Seabed Authority observers, including those at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and TU Delft, have examined potential environmental impacts of nodule collection and compared it to the environmental and human impact of terrestrial mining.[31][32] In April 2021, scientists from JPI oceans project carried out in depth studies into mining technology and its possible effect on the seabed.[33]

Much of what is known about the potential environmental impact is a result of a dredging pilot test conducted in 1978. In the years since the tests, the region has been monitored. Many species here are more susceptible to the negative effects of environmental shifts as change at these depths is atypical. Specifically looking at nematodes, it has been determined that there is a lower species richness and lower total biomass in the area where the dredging occurred as compared to the neighboring spaces. Additionally, the composition of species and the frequencies at which they are found change with human interference. The removal of polymetallic nodules, as proposed through deep-sea mining, would decrease suitable habitat as many species of nematodes reside within the upper five centimeters where nodules exist, too. Even those species that do remain will face changes to their habitat conditions as the new top layer of sediment after the removal of the nodules will be significantly denser. The low sedimentation levels and minimal currents show that disruption in the CCZ would have long-lasting effects on the environment; the upturned sediment remains unsettled even decades later.[34]

In addition, Seabed mining may lead to prolonged impact to the nodule provinces.[9] Polymetallic nodules in the CCZ grow extremely slowly, at rates of approximately 1–10 millimeters per million years.[7] Polymetallic nodules are classified in three morphologies, smooth (S-type), rough (R-type), and mixed (S–R) .[7] Their formation is conditioned by a combination of metal supply, availability of nuclei, benthic currents, sediment–water interface conditions, biological mixing (bioturbation), and internal stratigraphic layering, which makes it difficult to reproduce quickly.[7] The species directly dependent on them, and all of their subsequent linkages or environmental functions would see vast changes that could not be quickly restored after the damage is complete.[29] Beyond direct physical contact with equipment, organisms may be affected by sediment plumes, change in resource availability, and noise and light pollution associated with mining operations; the latter effect remain largely unknown.[34] [35]

Some scholars have raised environmental concerns regarding legal and governance issues in the CCZ. While UNCLOS requires that activities in the Area provide "effective protection" of the marine environment, the ISA simultaneously administers mineral development and environmental protection.[4] Surveys of extensive undescribed biodiversity and environmental effects have led some commentators and governments to argue that the current ecological baselines are limited. Accompanied with ongoing debates over draft mining regulations, implementation of environmental thresholds, and the role of precaution in the ISA's decision-making processes, mining activities remain controversial at the CCZ.[4]

Remove ads

References

Links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads