Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

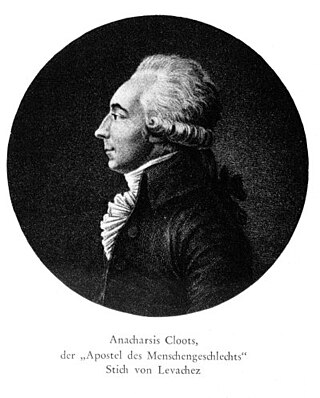

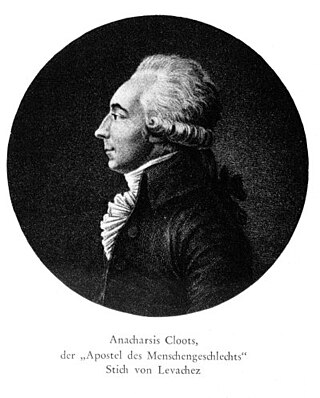

Anacharsis Cloots

Prussian nobleman (1755–1794) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Jean-Baptiste du Val-de-Grâce, baron de Cloots (24 June 1755 – 24 March 1794), better known as Anacharsis Cloots (also spelled Clootz), was a Prussian nobleman who was a significant figure in the French Revolution.[1][2][3] Perhaps the first to advocate a world parliament, an idea later espoused by Albert Camus and Albert Einstein, he was a world federalist and an internationalist anarchist. According to Siegfried Weichlein, he was nicknamed "orator of mankind", "citizen of humanity" and "a personal enemy of God".[4] However, only the title of "Orator of the Human Race" is one that Cloots actually did give himself with a specific rhetorical meaning in the classical republican tradition of the revolutionaries; it was a way to participate to the French Revolution despite not holding a French citizenship and to mock the official "representative" of his own country, seen as only representing the king and not the people for Cloots.[5] American author Herman Melville refers to an "Anacharsis Clootz deputation" as a representation of global humanity in both Moby-Dick (1851), The Confidence-Man, and later in Billy Budd.[6][7]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Early life

Born near Kleve, at the castle of Gnadenthal, he belonged to a noble Prussian family of Dutch Protestant origin.[8] The young Cloots, heir to a great fortune, was sent to Paris at age eleven to complete his education, and became attracted to the theories of his uncle the abbé Cornelius de Pauw (1739–1799), philosophe, geographer and diplomat at the court of Frederick II of Prussia, aka Frederick the Great. Cloots studied at the prestigious Berlin académie militaire des nobles established by Frederick and his plan for balancing military and academic education among the nobility.[9]

Revolution

On the breaking out of the Revolution, Cloots returned in 1789 to Paris, thinking the opportunity favorable for establishing his dream of a universal family of nations. On 19 June 1790 he appeared at the bar of the National Constituent Assembly at the head of thirty-six foreigners, and, in the name of this embassy of the human race, declared that the world adhered to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. After this, he was known as the orator of the human race, by which title he called himself, dropping that of baron, and substituting for his baptismal names the pseudonym of Anacharsis, from Jean-Jacques Barthélemy's famous philosophical romance Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece.[10]

In 1792 he placed 12,000 livres at the disposal of the French Republic for the arming of forty or fifty fighters in the cause of man against tyranny (see French Revolutionary Wars). After the riots of 10 August he became an even more prominent supporter of new ideas. Some authors have erroneously perpetuated the claim that Cloots had declared himself "the personal enemy of Jesus Christ",[11] abjuring all revealed religions,.[10] However, as Roland Mortier has shown, this statement is nowhere to be found in his writings or speeches.[12] The false claim that Cloots had called himself "personal enemy of Jesus Christ" likely stems from an apocryphal epithet ironically given to him following his death, which was then later propagated by counter-revolutionaries until it entered in the works of historians.[13]

Convention

In the same month he had the rights of French citizenship conferred on him; and, having in September been elected a member of the National Convention, he voted in favor of capital punishment for King Louis XVI, justifying it in the name of the human race, and was an active partisan of the war of propaganda.[10]

Execution

Excluded at the insistence of Maximilien Robespierre from the Jacobin Club, he remained a foreigner in many eyes. When the Committee of Public Safety levelled accusations of treason against the Hébertists, they also implicated Cloots to give substance to their charge of a foreign plot. Although his innocence was manifest, he was condemned and subsequently guillotined on 24 March 1794.[14] He followed Vincent, Ronsin, Momoro and the rest of the Hébertist leadership to the scaffold, although he was not an Hébertist himself, in front of the largest crowd ever assembled for a public execution.[15] Their death was a sort of carnival, a pleasant spectacle according to Michelet's witnesses.

Remove ads

Thought

Cloots was an original political thinker who crafted his own interpretation of the meaning of the French Revolution. He was a proponent of the world state, and he sought to promote a more broad-minded and internationalist understanding of the Revolution's potential. He imagined the institutions of the world state along the lines of those of the French Revolutionary Republic. Cloots's thought was expressed in several works, most importantly in his Bases constitutionnelles de la République du genre humain.[16]

Remove ads

Works

- La Certitude des preuves du mahométisme (London, 1780), published under the pseudonym of Ali-GurBer, in answer to Nicolas-Sylvestre Bergier's Certitude des preuves du christianisme

- L'Orateur du genre humain, ou Dépêches du Prussien Cloots au Prussien Herzberg (Paris, 1791)

- La République universelle ou adresse aux tyrannicides (1792).

- Adresse d'un Prussien à un Anglais (Paris, 1790), 52 p.

- Bases constitutionnelles de la République du genre humain (Paris, 1793), 48 p.

- Voltaire triomphant ou les prêtres déçus (178?), 30 p. Attributed to Cloots.

- Discours prononcé à la barre de l'Assemblée nationale par M. de Cloots, du Val-de-Grâce,... à la séance du 19 juin 1790 (1790), 4 p.

Notes

References and further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads