Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Croatisation

Process of cultural assimilation into Croatian identity From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Croatisation or Croatization (Serbo-Croatian: kroatizacija, hrvatizacija, pohrvaćenje; Italian: croatizzazione) is a process of cultural assimilation, and its consequences, in which people or lands ethnically only partially Croatian or non-Croatian become Croatian.

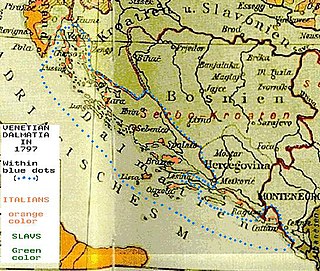

Croatisation of Italians in Dalmatia

Summarize

Perspective

Even with a predominant Croatian majority, Dalmatia retained relatively large Italian-speaking communities in the coastal cities. Many Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy.[1][better source needed] However, after 1866, when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom of Italy, Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic. This triggered the gradual rise of Italian irredentism among many Italians in Dalmatia, who demanded the unification of the Austrian Littoral, Fiume and Dalmatia with Italy. As Italian was the language of administration, education, the press, and the Austrian navy before 1859, people who wished to acquire higher social standing and separate from the Slav peasantry became Italians.[2] In the years after 1866, Italians lost their privileges in Austria-Hungary, their assimilation of the Slavs came to an end, and they found themselves under growing pressure by other rising nations; with the rising Slav tide after 1890, italianized Slavs reverted to being Croats.[2] Austrian rulers found use of the racial antagonism and financed Slav schools and promoted Croatian as the official language, and many Italians chose voluntary exile.[2]

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[3]

His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard. His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.

Dalmatia, especially its maritime cities, once had a substantial local Italian-speaking population (Dalmatian Italians). According to Austrian censuses, the Italian speakers in Dalmatia formed 12.5% of the population in 1865,[6] but this was reduced to 2.8% in 1910.[7] The Italian population in Dalmatia was concentrated in the major coastal cities. In the city of Split in 1890 there were 1,971 Dalmatian Italians (9% of the population), in Zadar 7,672 (27%), in Šibenik 1,090 (5%), in Kotor 646 (12%) and in Dubrovnik 356 (3%).[8] In other Dalmatian localities, according to Austrian censuses, Italians experienced a sudden decrease: in the twenty years 1890-1910, in Rab they went from 225 to 151, in Vis from 352 to 92, in Pag from 787 to 23, completely disappearing in almost all inland locations.

There are several reasons for the decrease of the Dalmatian Italian population following the rise of European nationalism in the 19th century:[9]

- The conflict with the Austrian rulers caused by the Italian "Risorgimento".

- The emergence of Croatian nationalism and Italian irredentism (see Risorgimento), and the subsequent conflict of the two.

- The emigration of many Dalmatians toward the growing industrial regions of northern Italy before World War I and North and South America.

- Multi generational assimilation of anyone who married out of their social class and/or nationality – as perpetuated by similarities in education, religion, dual linguistic distribution, mainstream culture and economical output.

- De-italianization of previously italianized Slavic people.

While Slavic-speakers made up 80-95% of the Dalmatia populace,[10] only Italian language schools existed until 1848,[11] and due to restrictive voting laws, the Italian-speaking aristocratic minority retained political control of Dalmatia.[12] Only after Austria liberalised elections in 1870, allowing more majority Slavs to vote, did Croatian parties gain control. Croatian finally became an official language in Dalmatia in 1883, along with Italian.[13] Yet minority Italian-speakers continued to wield strong influence, since Austria favoured Italians for government work, thus in the Austrian capital of Dalmatia, Zara, the proportion of Italians continued to grow, making it the only Dalmatian city with an Italian majority.[14]

Both Italian and Croatian were recognized as official languages in Dalmatia until 1909, when Italian lost its official status, thus it could no longer be used in the public and administrative sphere.[15] After the World War I, Dalmatia was annexed to Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and the Italian community underwent a policy of forced Croatisation.[16] The majority of the Italian Dalmatian minority decided to transfer in the Kingdom of Italy.[17]

During the Italian occupation of Dalmatia in World War II, it was caught in the ethnic violence towards non-Italians during fascist repression. What remained of the Italian community in Dalmatia fled the area after World War II during the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus:[18] from 1947, after the war, Dalmatian Italians were subject by Yugoslav authorities to forms of intimidation, such as nationalization, expropriation, and discriminatory taxation,[19] which gave them little option other than emigration.[20][21][22]

In 2001 about 500 Italians were counted in Dalmatia. In particular, according to the official Croatian census of 2011, there are 83 Italians in Split (equal to 0.05% of the total population), 16 in Šibenik (0.03%) and 27 in Dubrovnik (0.06%).[23] According to the official Croatian census of 2021, there are 63 Italians in Zadar (equal to 0.09% of the total population).[24]

Remove ads

Croatisation in the NDH

Summarize

Perspective

Areas annexed by Italy: the area constituting the province of Ljubljana, the area merged with the province of Fiume and the areas making up the Governorate of Dalmatia

The Croatisation during Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was aimed primarily towards Serbs, and to a lesser degree, towards Jews and Roma. The Ustaše aim was a "pure Croatia" and the main target was the ethnic Serb population of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ministers of NDH announced the goals and strategies of the Ustaše in May 1941. The same statements and similar or related ones were also repeated in public speeches by single ministers, such as Mile Budak in Gospić and, a month later, by Mladen Lorković.[25]

- One third of the Serbs (in the Independent State of Croatia) were to be forcibly converted to Catholicism

- One third of the Serbs were to be expelled (ethnically cleansed)

- One third of the Serbs were to be killed

A Croatian Orthodox Church was established in order to try and pacify the state as well as to Croatisize the remaining Serb population once the Ustaše realized that the complete eradication of Serbs in the NDH was unattainable.[26]

Remove ads

Notable individuals who voluntarily Croatised

Summarize

Perspective

- Dimitrija Demeter, a playwright who was the author of the first modern Croatian drama, was from a Greek family.

- Vatroslav Lisinski, a composer, was originally named Ignaz Fuchs. His Croatian name is a literal translation.

- Bogoslav Šulek, a lexicographer and inventor of many Croatian scientific terms, was originally Bohuslav Šulek from Slovakia.

- Stanko Vraz, a poet and the first professional writer in Croatia, was originally Jakob Frass from Slovenia.

- August Šenoa, a Croatian novelist, poet and writer, is of German descent. His parents never learned the Croatian language, even when they lived in Zagreb.

- Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger, a geologist, palaeontologist and archaeologist who discovered Krapina man[27] (Krapinski pračovjek), was of German descent. He added his second name, Gorjanović, to be adopted as a Croatian.

- Slavoljub Eduard Penkala was an inventor of Dutch/Polish origins. He added the name Slavoljub in order to Croatise.

- Lovro Monti, Croatian politician, mayor of Knin. One of the leaders of the Croatian national movement in Dalmatia, he was of Italian roots.

- Adolfo Veber Tkalčević, linguist of German descent

- Ivan Zajc (born Giovanni von Seitz) a music composer was of German descent

Other

Notable individuals, of Croatian origin, partially Magyarized through intermarriages and then Croatized again, include families:

See also

- Cultural assimilation

- Anti-Croat Sentiment

- Bosniakisation

- Germanisation

- Italianization

- Magyarization

- Serbianisation

- Serbs of Croatia

- Istrian–Dalmatian exodus

- Dalmatian Italians

- Istrian Italians

- Forced assimilation

- Independent State of Croatia

- Ustaše

- Genocide of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia

- Greater Croatia

Notes

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads