Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Cyriacus of Ancona

15th-century humanist and antiquarian from the Republic of Ancona From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Cyriacus of Ancona or Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli (31 July 1391 – 1452) was a humanist and antiquarian who came from a prominent family of merchants in Ancona, a maritime republic on the Adriatic coast of the Italian Peninsula. He has been called the "Father of Archaeology":

"Cyriac of Ancona was the most enterprising and prolific recorder of Greek and Roman antiquities, particularly inscriptions, in the fifteenth century, and the general accuracy of his records entitles him to be called the founding father of modern classical archeology."[3]

Remove ads

Life

Summarize

Perspective

His first voyage was made at the age of nine, in the familia of his mother's brother, for commercial reasons. Unlike many library antiquarians, Cyriacus was not content to study classical texts: to satisfy his desire to rediscover antiquity, sailed the Mediterranean in search of historical evidence. He noted down his archaeological discoveries in his day-book, Commentaria, that eventually filled seven volumes. He made numerous voyages in Southern Italy, Dalmatia and Epirus and into the Morea, to Egypt, to Chios, Rhodes and Beirut, to Anatolia and Constantinople,[Note 1] during which he wrote detailed descriptions of monuments and ancient remains, illustrated by his drawings.

His years in Rome studying Latin are commemorated by his drawings of many of the monuments and antiquities of ancient Rome. In Constantinople he studied Greek. He enjoyed the patronage of Eugenius IV, who had been Papal legate in the March of Ancona from 1420 to 1422, Cosimo de' Medici, and the Visconti of Milan. He was in Siena at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, and when Sigismund came to Rome for his coronation as Emperor, Cyriacus was his guide among Rome's antiquities. Two years later in 1435, Cyriacus was back exploring in Greece and Egypt.

In 1435 Cyriacus visited and rediscovered the true nature of the Great Pyramid, which until then was believed to be one of Joseph's granaries and in 1436 that of the Parthenon, which until then was considered only the largest church in Athens.

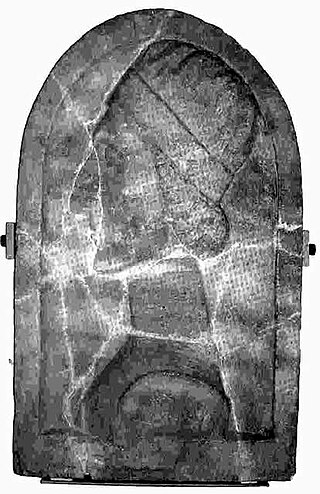

He was probably the first traveler who recognized the importance of the ruins of Eretria: on 5 April 1436, he described and sketched a plan of the ancient city walls, indicating the position of the theatre and the fortifications of the acropolis and mentioning the existence of inscriptions.[5] He also visited and recognized Apollonia (Illyria), Nicopolis, Butrint and Delphi[3]. He collected a great store of inscriptions, manuscripts, and other antiquities. Through a drawing made for Cyriacus, the appearance of the Column of Justinian is recorded for us, before it was dismantled by the Ottomans. He returned in 1426 after having visited Rhodes, Beirut, Damascus, Cyprus, Mytilene, Thessalonica, and other places[3].

Pushed by a strong curiosity, he also bought a great number of documents which he used to write six volumes of Commentarii ("Commentaries"). The ravages of time have been unkind to Cyriacus's lifework, which he never published, but which fortunately circulated in manuscript and in copies of his drawings. For a long time it was mistakenly believed that the last manuscript of the Commentarii had been lost in the fire of the library of Alessandro Sforza and Costanza Varano in Pesaro; This erroneous statement unexpectedly had a very large following.[6]

He retired to Cremona, where he died in 1452, according to the Trotti manuscript, now held in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.[7] Long after his death, some surviving texts were printed: Epigrammata reperta per Illyricum a Kyriaco Anconitano (Rome, 1664), Cyriaci Anconitani nova fragmenta notis illustrata, (Pesaro, 1763) and Itinerarium (Florence, 1742).

Remove ads

Founding father of Archeology

Summarize

Perspective

His detailed on-site observations, particularly in Greece, Asia Minor and Egypt, make him the founding father of modern archaeology[3]. Furthermore, his accuracy as a meticulous epigrapher was praised by Giovanni Battista de Rossi[8]; Theodor Mommsen considered him the founding father of epigraphy[9].

His vocation dates back to 1421, when scaffolding was erected around Arch of Trajan in his city for restoration. This presented Cyriacus, then thirty years old, with an extraordinary opportunity to climb the scaffolding and observe the monument up close; the harmonious proportions, the purity of the Proconnesian marble, and the ancient inscriptions were irresistible to Cyriacus. He tried to imagine the arch's original appearance and, based on the inscriptions on it, hypothesized the presence of gilded bronze statues of Trajan, his wife Plotina, and his sister Marciana on the attic.[10]

In 1435, Cyriacus went to Egypt and reached the Giza Plateau after sailing on the Nile; Comparing what he saw with his reading of the second book of the "Histories" by Herodotus, he rediscovered the true nature of the Great Pyramid and correcting centuries of misunderstandings. Cyriacus of Ancona thus definitively refuted the false identification of the Great Pyramid with one of the Joseph's Granaries and left several drawings of the monument and an account, reported in his Commentarii. Thanks to his numerous travels in Greece and Asia Minor, he was also able to testify that the pyramids of Giza were the only one of the Seven Wonders of the World to have survived the centuries. Through the writings of Ciriaco, this news spread first in Italian humanist circles and then among European scholars[11][12].

The rediscovery of the Parthenon as an ancient monument is also due to Cyriacus: in 1436 he was the first after antiquity to describe the Parthenon and to call it by his name, of which he had read many times in ancient texts, including that of Pausanias Periegetes. Thanks to him, Western Europe was able to have the first design of the monument, which Ciriaco called "temple of the goddess Athena", unlike previous travellers, who had called it "church of Virgin Mary":[11]

...mirabile Palladis Divae marmoreum templum, divum quippe opus Phidiae ("...the wonderful temple of the goddess Athena, a divine work of Phidias").

In 1436, Cyriacus of Ancona rediscovered the site of Delphi during his maritime voyages in search of relics from the classical era. He visited Delphi in March and stayed there for six days. He recorded all the visible archaeological remains, basing his identification on Pausanias' text. He described the stadium and the theater, as well as some sculptures. He also recorded several inscriptions, most of which are now lost.[13]

Cyriacus himself explains the spirit that animated him:[10]

Driven by a strong desire to see the world, I have devoted and devoted myself entirely, both to completing the investigation of what has long been the principal object of my interest, namely the vestiges of antiquity scattered throughout the Earth, and to being able to commit to writing those which day by day fall into ruin through the long work of devastation of time due to human indifference...

— Cyriacus of Ancona, Itinerarium

These words are now known as "The Oath of Cyriac" and were used as the title of a documentary film released in 2022 by Andorran director Olivier Bourgeois, which recounts the heroism of those who worked to preserve cultural heritage from the ravages of war. The "The Oath of Cyriac" as applied to archaeologists, therefore parallels the Hippocratic Oath of physicians[14].

Also significant is the praise to archaeology that Ciriaco left us:[15]

O great and absolutely divine power of our art!

For during our lifetime, those things which had been alive and shining among the living, lay dead, buried by the long ruin of time and the long injury of the half-living: finally recalled by that divine art from the underworld to the light, they will finally live again among living men, through the most happy restoration of time.

— Cyriacus of Ancona, Epistola I (to Giovanni Ricinati)

Also noteworthy is his fundamental contribution to the recovery of Roman epigraphic writing, made possible thanks to his work, which goes beyond the mediation of Carolingian writing: according to Ciriaco, the only true Roman lapidary character must be sought only in the examination of ancient epigraphs, without resorting to medieval mediations. In Dubrovnik, in 1443-1444, he composed two Latin inscriptions, one in the loggia of the Rector’s Palace, and the other on the fountain erected by the architect Onofrio della Cava; they were the first examples of monumental capitals all'antica to be seen in Dubrovnik.[16]

Remove ads

Notes

References

Sources

Studies

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads