Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Deccanis

Ethnoreligious community in India From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Deccanis or Deccani people are an Indo-Aryan ethno-religious community of Deccani-speaking Muslims who inhabit or are from the Deccan region of India.[2] The community traces its origins to the shifting of the Delhi Sultanate's capital from Delhi to Daulatabad in 1327 during the reign of Muhammad bin Tughluq.[3] Further ancestry can also be traced from immigrant Muslims referred to as Afaqis,[4] also known as Pardesis who came from Central Asia, Iraq and Iran and had settled in the Deccan region during the Bahmani Sultanate (1347). The migration of Muslim Hindavi-speaking people to the Deccan and intermarriage with the local Hindus who converted to Islam,[5] led to the creation of a new community of Hindustani-speaking Muslims, known as the Deccani, who would come to play an important role in the politics of the Deccan.[6] Their language, Deccani, emerged as a language of linguistic prestige and culture during the Bahmani Sultanate, further evolving in the Deccan Sultanates.[7]

Following the demise of the Bahmanis, the Deccan Sultanate period marked a golden age for Deccani culture, notably in the arts, language, and architecture.[8] The Deccani people form significant minorities in the Deccan, including the Maharashtran regions of Marathwada and Vidarbha, and the states of Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka (except Tulu Nadu) and northern Tamil Nadu. They form a majority in the old cities of Hyderabad and Aurangabad.[9][10] After the Partition of India and the annexation of Hyderabad, large diaspora communities formed outside the Deccan, especially in Pakistan, where they make up a significant portion of the Urdu speaking minority, the Muhajirs.[11]

The Deccani people are further divided into various groups that can broadly be lumped into three: the Hyderabadis (from Hyderabad State which includes Hyderabad, Osmanabad, and Aurangabad), Mysoris (from Mysore state, including Bangalore), and Madrasis (from Madras state, including Kurnool, Nellore, Guntur and Chennai). Deccani is the mother tongue of most Muslims in the states of Karnataka, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, and it is spoken by a section of Muslims in Maharashtra, Goa, Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The word Deccani (Persian: دکنی from Prakrit dakkhin "south") was derived in the court of Bahmani rulers in 1487 AD during Sultan Mahmood Shah Bahmani II.[12]

- A medieval Deccani Muslim horseman

- Map of the Bahmanid empire

The Bahmanid empire was founded by Hasan Gangu, or also known as Zafar Khan, a ruler of Afghan or Turk origin. following the Rebellion of Ismail Mukh.[13][14][15][16][17][18] Hasan Gangu revolted against the Tughlaq dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate, with the revolt being led by another Afghan, named Ismail Mukh.[19] Ismail Mukh succeeded and then abdicated in favor of Zafar Khan, who founded the Bahmani Sultanate.[19][20] Hasan Gangu was one of the inhabitants of Delhi who were forced to immigrate to Daulatabad in the during the Delhi Sultanate, with the purpose of building a large Muslim urban centre in the Deccan.[21]

Vijayanagara Wars

The Bahmanids' aggressive confrontation with the two main Hindu kingdoms of the southern Deccan, Warangal and Vijayanagar, made them renowned among Muslims as warriors of the faith.[22] Ahmad Shah Bahmani I conquered Warangal kingdom in 1425, annexing it to the empire. The Vijayanagar empire, which had subdued the Madurai Sultanate after a conflict lasting four decades, found a natural enemy in the Bahmanids of the northern Deccan, over the control of the Godavari-basin, Tungabadhra Doab, and the Marathwada country, although they seldom required a pretext for declaring war.[23] Military conflicts between the Bahmanids and Vijayanagara were almost a regular feature and lasted as long as these kingdoms continued. These military conflicts resulted in widespread devastation of the contested areas by both sides, resulting in considerable loss of life and property.[24] Military slavery involved captured slaves from Vijayanagar and having them embrace a Deccani identity by converting them to Islam and integrating into the host society, so they could begin military careers within the Bahmanid empire. This was the origin of powerful political leaders such as Nizam-ul-Mulk Bahri.[25][26]

Deccan Sultanates

The five Deccan Sultanates of diverse origins continued to identify as successor states of the Bahmanid dynasty as the basis of legitimacy, and minted Bahmanid coins rather than issue their own coins.[27] The Nizam Shahs and Berar Shahs were founded by the heads of the Deccani Muslim party.[28][29] The Adil Shahi Sultanate, which was founded by a Shia Georgian slave, also switched to a Deccani ethnic and political identity under Ibrahim Adil Shah I, who established Sunnism (the religion of the Deccani Muslims).[30][31] He degraded the Afaqis (Persians) and dismissed them from their posts with a few exceptions, replacing them with nobles of the Deccani party.[32][33][34][35] Uniting in a coalition under the leadership of Hussain Nizam Shah, the Nizam Shahi Sultan, the five Deccan Sultanates defeated the Hindu Vijayanagar empire in the Battle of Talikota, resulting in the Sack of Vijayanagara. Hussain Nizam Shah personally beheaded the Vijayanagar Emperor, Rama Raya.[36]

- The Malik-i Maidan cannon

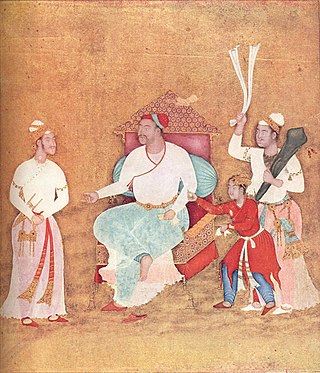

- Sultan Hussain Nizam Shah I beheads Rama Raya

- Ruins of Vijayanagar

Pindaris

The first mention of the Pindaris referred to Muslim mercenaries generally settled in the districts of Bijapur, who had served as mercenaries for the armies of most of the Muslim Deccani kingdoms. They took part in the numerous wars against the Mughals of Delhi. The disintegration of the Muslim kingdoms of the Deccan led to the gradual disbandment of the Pindaris. These were at that stage taken in the service of the Marathas. The inclusion of the Pindaris eventually became an indispensable part and parcel of the Maratha army. As a class of freebooters in Maratha armies they acted as a "sort of roving cavalry...rendering them much the same service as the Cossacks for the armies of Russia." The Pindaris would also later be used by kings such as Tipu Sultan.[37]

18th century

Muslim military men with Deccani background were much sought after by the Marava and Kallar warrior chiefs of the south Indian hinterland. Their fortress towns soon acquired concentrations of migrant Deccanis and Urdu-speaking service people, mostly Sunnis. These incomers included seasoned fighters who had seen service with the Mughals and the Muslim states in northern India.[38] This was the source of the phenomenal rise of rulers such as Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan.

Sultanat-i-Khudadad of Mysore

Hyder Ali had initially served as an ordinary soldier for the Hindu Wadiyar Kingdom of Mysore and became a cavalry officer in 1749. Once he took control of the army, he took advantage of court politics, stormed into Srirangapatna, and proclaimed himself ruler. Having styled himself as sultan in 1761, Hyder Ali launched a preemptive war against the Marathas, westernizing the army of Mysore in the process and developing the first successful iron-cased rockets as an artillery weapon. With the withdrawal of Madhav Rao, he overran the borderlands between the kingdoms and seized land and immense booty, increasing his power.[39] Ultimately, this brought him into conflict with the East India Company, between whom a series of wars would begin. His son and successor Tipu Sultan would inherit both conflicts. He saw victory against the Marathas and allied with the French in order to fight the British and their allies. Eventually, after existing for 38 years, the Deccani Muslim Sultanat-e-Khudadad (transl. God-gifted kingdom) would be defeated by an alliance of the British, Hyderabad and the Marathas, and the Wadiyars were reinstated on the Mysori throne.

- Territories of the original Wadeyar kingdom

- Hyder's Dominions in 1780

- Hyder Ali as 'The Pretended Fakir'

- Sir David Baird Discovering Body of Tipu Sultan

Partition Era (1940s-1950s)

During Partition, the Deccani Muslim community—stretching beyond Hyderabad into surrounding regions of the Deccan—lived under a mix of political structures. The largest concentration was in the princely state of Hyderabad, but significant Deccani Muslim populations also lived in Maharashtra and parts of Karnataka and the Madras Presidency (Andhra areas). In Hyderabad State, Muslims—though a minority—held a disproportionate share of political, military, and administrative posts under the Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan. Elsewhere in the Deccan, Muslims were active in trade, landholding, artisan work, and small-scale industry. By the late colonial era, political awareness was rising, with some Deccani Muslims drawn to Congress-led nationalist politics, others aligned with local Muslim organizations such as the Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen (MIM), and a smaller number sympathetic to the Muslim League. However, unlike in Punjab or Bengal, support for the League’s Pakistan demand was scattered; most Deccani Muslims were more concerned with preserving cultural identity and local autonomy than joining a separate Muslim nation.

During the Partition period (1946–1948), the experience of Deccani Muslims was unique compared to northern India. Violence during 1947 was not at a similar scale in most Deccan regions, largely because Hyderabad State had not yet acceded to India or Pakistan. The Nizam attempted to keep Hyderabad independent, which drew in political tensions with both India and internal opposition movements like the Telangana armed peasant rebellion. By 1948, the rise of the Razakars, a paramilitary force supporting the Nizam, intensified Hindu-Muslim tensions in rural areas. When India annexed Hyderabad in Operation Polo (September 1948), the transition was accompanied by violent reprisals, particularly in districts of Marathwada and northern Karnataka. The Sunderlal Committee Report later documented tens of thousands to a hundreds of thousands of Muslim deaths, mass displacements, and widespread property loss)[40][41]. While some urban Muslim elites and professionals fled to Pakistan assimilating into the larger Muhajir community between 1947 and 1954, a significant number of Deccani Muslims—especially in smaller towns and rural areas—remained, albeit under altered socio-political circumstances.[42] In Hyderabad City a notable number of Hyderabadi Muslims emigrated from the then integrated Indian state of Andhra Pradesh to Pakistan, the UK, the U.S. and Canada, resulting in a large diaspora.[43][44]

From 1948 to 1956, Deccani Muslims navigated a period of adjustment to the Indian Union. Hyderabad State was administered by a military governor before slowly being integrated into democratic governance. In the broader Deccan, Muslims faced economic displacement as old feudal structures were dismantled, and Urdu-medium education lost state patronage. Still, the community remained culturally vibrant, continuing traditions in language, cuisine, and arts. Politically, Muslims became active in emerging state legislatures, municipal bodies, and professional associations, though often from a reduced position of influence. The linguistic reorganization of states in 1956—which split Hyderabad State into parts of Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh—further dispersed the Deccani Muslim population across different administrative units.[45]

Post Partition Era (1960s-1990s)

Socio-Economic Challenges and Cultural Resilience (1960s–1990s):

From the 1960s to the 1990s, Deccani Muslims in Maharashtra, Telangana, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh navigated a period of transformation and adaptation. Following the political integration of Hyderabad State into India and the reorganization of states along linguistic lines, the community had to adjust to new administrative, educational, and economic structures. Traditional sources of influence, including positions in the Nizam’s administration and court patronage, were largely gone, which pushed many Deccani Muslims toward trade, small businesses, government jobs, and professional careers. Urban centers such as Hyderabad, Aurangabad, Bidar, and Latur became hubs for social mobility, while rural areas often faced greater economic challenges. Throughout this period, Deccani Muslims maintained strong cultural traditions—especially in language, music, and cuisine—which provided continuity and a sense of identity in rapidly changing social environments.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the community faced new opportunities and challenges. Migration to Mumbai, Pune, Bangalore, and international destinations like the Gulf, UK, and North America provided economic prospects and transnational networks but also raised questions about maintaining linguistic and cultural traditions. At the same time, urbanization, rising educational aspirations, and participation in business and professional sectors helped foster a more visible and influential Deccani Muslim presence in public life. Despite facing socio-economic marginalization in some regions, the community retained a distinct identity, blending historical Deccani cultural heritage with modern urban and transnational experiences, which laid the groundwork for political, social, and cultural initiatives in the decades that followed.

Present Day Status (2000s-2020s)

Between the 2000s and 2020s, Deccani Muslims across Maharashtra, Telangana, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh experienced both political empowerment and cultural challenges. In Maharashtra, the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) made significant electoral strides. In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, Imtiyaz Jaleel secured the Aurangabad seat, defeating the Shiv Sena candidate by a narrow margin of 4,492 votes. This victory marked the first time an AIMIM candidate won a Lok Sabha seat in Maharashtra. However, in the 2024 elections, Jaleel's seat was lost to the Shiv Sena candidate, highlighting the volatile nature of regional politics. Concurrently, Waris Pathan contested the Byculla Assembly seat in 2019, garnering 31,157 votes but did not win. AIMIM's presence in Maharashtra grew, with the party contesting 44 seats in the 2019 Assembly elections, a significant increase from previous years. In Karnataka, AIMIM made inroads by contesting local body elections and establishing a presence in cities with substantial Deccani Muslim populations.

The rise of Hindutva ideologies, championed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Shiv Sena, posed challenges for Deccani Muslims. Efforts to rename cities with historical Muslim associations, such as Aurangabad to Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar and Osmanabad to Dharashiv, were part of this broader agenda. These moves were perceived by many as attempts to erase Muslim heritage and identity in the Deccan region. Alongside this, measures such as the hijab ban in Karnataka were viewed as direct affronts to the cultural and religious rights of Deccani Muslims, deepening feelings of exclusion and marginalization. Amidst these political challenges, the community also faced the struggle of maintaining their linguistic heritage. Urdu, once a lingua franca in the Deccan region, experienced a steady decline in usage. Factors such as its marginalization in educational institutions and its politicized association with Muslim identity contributed to its reduced prominence. Efforts to promote and preserve the language met with varying degrees of success, as the community continued to navigate the complexities of cultural retention in a rapidly changing socio-political landscape.

Despite political and cultural challenges, Deccani Muslims continued to preserve and promote their rich cultural heritage. Cities like Hyderabad, Aurangabad, and Bidar remain centers for traditional music, cuisine, and festivals.

Remove ads

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

Painting

Deccani style painting originated in the 16th century in the Deccan region, containing an insightful native style with the blend of Persianate techniques and is similar to neighbouring Vijayanagara paintings. Due to Islamic influence, Deccani paintings are mostly of nature and inspired by local floral and fauna. Some Deccani paintings present the historical events of the region.[46][47]

Handicraft

The craftspersons of Bidar were so famed for their inlay work on copper and silver that it came to be known as Bidri.[48] It was developed in the 14th century C.E. during the rule of the Bahmani Sultans.[48] The term "bidriware" originates from the township of Bidar, which is still the chief center of production.[49] Bidriware is a Geographical Indication (GI) awarded craft of India.[48]

Music & Dance

Deccani music and dance have deep roots in the Deccan Sultanates and later the Nizam’s courts, blending influences from Arabic, African, Persian, and regional traditions. One prominent form is Marfa, a high-energy celebratory ensemble introduced by Siddi and Chaush communities—Afro-Arab soldiers in the Nizam’s army. It features rhythmic drumming with instruments like the marfa (kettledrum), daff, dhol, and metal clappers, and is often accompanied by vigorous sword-and-cane dance routines resembling Yemen’s Bar’a performance[50]. Another beloved tradition is Dholak ke Geet, informal folk songs sung by Deccani women during wedding ceremonies or daily household tasks, passed down orally for generations; these are accompanied by the ubiquitous dholak drum and imbued with local humor, satire, and social commentary.

Today, while some classical dance traditions once patronized by Deccani elites—such as Kathak during the era of Mah Laqa Bai—have diminished among Muslims, new forms continue to thrive at weddings and cultural gatherings. Marfa music remains a vibrant fixture at Hyderabadi Muslim marriages and public celebrations, symbolizing regional identity and heritage. Present-day wedding ceremonies also feature Dholak ke Geet, preserving oral folk traditions[51]. Moreover, Qawwali—once featured in royal courts and Sufi shrines—remains popular in Hyderabad, Aurangabad, Bidar, Nanded, Bijapur through performances at dargahs and poetry gatherings. Together, these traditions exemplify the syncretic and living performing arts culture of Deccani Muslims—rooted in history, yet vibrant in community life today.

Remove ads

Language

Summarize

Perspective

Historical Origins of Deccani Urdu

Deccani Urdu originated in the 14th century when Muhammad bin Tughluq moved his capital from Delhi to Daulatabad, leading to the southward migration of Delhi's Dehlavi-Hindavi speech. Over the subsequent centuries, this dialect, influenced by local tongues like Marathi, Telugu, Kannada, and Tamil, merged into what became known as Deccani or Dakhni—a linguistic blend that served as the vernacular lingua franca across the Muslim-ruled Deccan.

Under the Deccan Sultanates (Golconda, Bijapur, Ahmadnagar), Deccani flourished as a distinct literary language. Rulers like Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah and Ibrahim Adil Shah II not only patronized Deccani poets but composed literary works in the dialect—such as ghazals, masnavi, and musical poetry—giving Deccani a strong cultural and cultural-linguistic identity distinct from northern Urdu.

Present-Day Status & Makeup of Deccani Urdu

Today, Deccani survives primarily as a spoken dialect, especially among Hyderabadis and communities across the Deccan, though its literary tradition has waned. Influences of English and regional languages are increasingly visible in modern usage, including on social media and in local Hyderabadi films and performances[52].

Hyderabad’s linguistic community continues to preserve Deccani's unique flavor—rich with regional lexical quirks (e.g., "nakko" for “no,” “houley” instead of “halke”) and distinctive syntactic patterns. While Standard Urdu has become the preferred literary and formal register, Deccani remains deeply rooted in everyday conversation and cultural identity.

See also

Further reading

- Urban Culture of Medieval Deccan (1300 A.D. TO 1650 A.D.)

- Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, Volume 22 (1963)

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads