Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

De balneis Puteolanis

1197 didactic poem by Peter of Eboli From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

De balneis Puteolanis ("On the baths of Pozzuoli") is a didactic poem in Latin attributed to Peter of Eboli, a medieval Italian poet. The poem has the alternative title De balneis terrae laboris, which translates to “The baths of the land of labor.” It was written in the last decade of the twelfth century, probably in 1197. The poem is dedicated to the emperor, probably Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor at the time of creation, with the inscription “Cesaris ad laudem.” Generally, the poem is referred to as having thirty-five epigrams (sections), but one study by D’Amato explores the feasibility that the original next could consist of thirty-nine epigrams. [1] The text itself details the numerous thermal baths of Pozzuoli in the Campi Flegrei region of Campania. It speaks to the therapeutic effect of the waters and celebrates them for their benefits. The oldest manuscript containing the poem is in the Angelica Library in Rome, approximately dated to the last half of the thirteenth to the early fourteenth century.

Remove ads

Peter of Eboli

Summarize

Perspective

The attribution of the poem to Peter of Eboli (Petrus de Ebulo) is generally made “with some certainty,” although some historians associate it with the work of Alcadino di Siracusa or Eustazio di Matera, as it was variously attributed in the late Middle Ages.[2] Huillard-Bréholles, in 1852, was the first to attribute the work to Peter.

Peter of Eboli is said to have flourished around 1196. He was certainly from Eboli, as he stated in his work many times. Very little is known about his life and much of it is not agreed upon by many scholars. It is true that “we do not know the exact dates of his life, but it is certain that he had died by July 1220.”[3] A parliamentary privilege issued by Emperor Frederick II in February 1221 confirmed the church of Salerno’s inheritance of the mills of Albiscenda in Ebolo which once belonged to Peter of Eboli.[4] Because of the exchange of property, it is likely that the poet had already died by that time.

There are no formal documents that establish a date of birth for Peter of Eboli.[1] One hypothesis about the author’s birth is put forth by De Angelis, who analyzed a manuscript miniature in the Liber ad honorem Augusti. Said miniature “shows Emperor Henry VI, Chancellor Conrad of Querfurt, and the poet as being of the same age.”[1] This observation makes it probable that when the work was commissioned in 1194/5, Peter of Eboli may have been thirty-five years old, and the approximate dates of his life can be calculated as c.1160–c.1220.[1]

Remove ads

Text and Illustrations

Summarize

Perspective

The original manuscript containing De balneis Puteolanis is lost, but twenty-eight copies survive. Many of the copies are profusely illustrated and provide source material for the importance of thermo-mineral bathing during the Middle Ages.[5] Its great number of surviving manuscripts, plus a version in Neapolitan dialect, French translations, and early printed editions are a testament to the success of the poem.[1] Almost all manuscripts originated in southern Italy and date to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

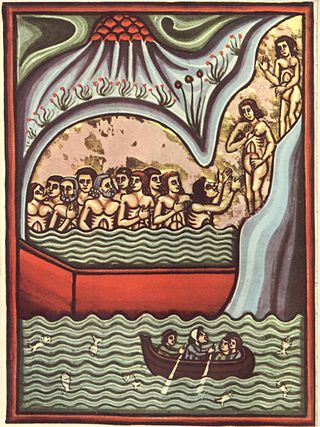

Most copies of the manuscript contain small amounts of text with half-page illustrations, namely Ms. 176 located at the University of Edinburgh. In this copy, illustrations occupy “the lower half of each page, probably inserted at a late date” and are described as “very roughly drawn and crudely colored.”[6] The beginnings of color shaded on each figure map out the tones the illustrator wished to utilize. A large body of water occupies the scene, one of the baths, as boats float on the calm water. A mountain range supports the background of the image, while nude bathers and fishermen are laid on the shore in the foreground. A small city facing the water is tucked away in the left corner.

The text begins in Latin with the sixth section and ends with the twenty-second section. The script utilized is Italian Gothic with red capitals and a large initial beginning, which is not historiated (decorated).

The classical origins of the decorations surrounding bathing scenes are portrayed on another page of the Edinburgh manuscript. A barrel-vaulted hall is depicted in a three-quarter perspective with an arched and pedimented door.[5] Several reclining nude figures personify the natural elements and harken back to the healing power of the waters. The overall architectural style of the hall as well as the inclusion of classical personifications and poses, point to the premedieval origins of the page’s decorations.[5]

Some scholars believe the poem was dedicated to Frederick II due to the expression nati tui in the last line of the final epigram, as it could be a reference to his son Henry VII, born in 1211.[1]

Remove ads

A Site for Bathing

Summarize

Perspective

The location depicted in the manuscript illustrations is Baiae, an important site for thermo-mineral bathing in antiquity. The volcanic region spans from the Bay of Puteoli (Pozzuoli) to the Cumaean Peninsula and was known as Campi Flegrei, the Phlegraen Fields, “fields devoured by fire.”[5] More broadly, the baths spanned an area between Naples, Pozzuoli, and Baiae.

De balneis Puteolanis acts as a testimony to the continued use of the site during the Middle Ages.[5] In prior days, information about the thermal mineral water in this area was communicated through inscriptions and guidebooks, setting a precedent for the celebrated tradition surrounding De balneis.[1] Architectural remains on the site also support this hypothesis. Rock structures such as walls, vaulted chambers, and colonnades that exist along the coast attest to the legacy of the area and the presence of several luxury palaces.[5]

The illustrations provided by the De balneis manuscripts provide a unique source of information for the practice of ancient baths and bathing. Technical and realistic details indicate that Peter’s original manuscript and his subsequent copies were based on eyewitness knowledge of the construction of the baths.[5] Three types of thermal facilities are portrayed in the illustrations: domed bath buildings, open-air pools for group immersion, and underground natural caves containing thermal sources.[5] Many structures are located near a body of water or a source of running water, and sometimes, a bather can be seen filling a pitcher to prepare for the bathing ritual. The pictorial evidence provided by copies of the manuscript has been studied closely, especially by those who specialize in the study of such topics and can recognize realism and specificity beyond what is traditionally noticed.

See also

References

Further reading

Gallery

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads