Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Encyclopædia Britannica (third edition)

1797 edition From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

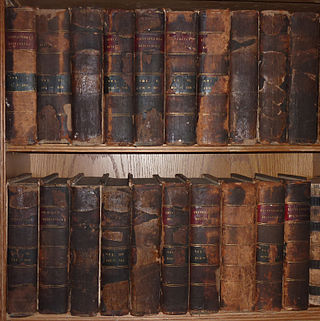

The third edition (1797) of the Encyclopædia Britannica was an encyclopedia published in eighteen volumes in quarto by Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell, in Edinburgh, Scotland. It represented a continuation of the encyclopedia founded by Bell and Macfarquhar in 1768. The third edition was the largest general encyclopedia to date in the English language, and the first one compiled by more than a handful of contributors.

Remove ads

History of the edition

Summarize

Perspective

The second edition of the Britannica had been finished in 1784. Already in 1788, Bell and Macfarquhar had published a prospectus for a third edition. In part, they feared competition from the revised edition of the Cyclopaedia edited by Abraham Rees, recently published in five volumes in folio. According to the prospectus, the third edition of the Britannica was to be published in 240 weekly numbers costing 1 shilling apiece, to be collected and bound in twelve volumes costing 1 guinea each. It was projected to feature 360 plates. Later in 1788, the publishers announced their intention of expanding the set to fifteen volumes.[1] By the time it was completed, the third edition occupied 18 volumes with 14,579 pages and 542 plates.[2] In 1801, a two-volume Supplement was added to the set.

As in the second edition of the Britannica, the volumes were published over a long period, from volume 1 in 1788 to volume 18 in 1797. Unlike those in the second edition, however, the title pages of the volumes in the third edition were not printed gradually as the volumes appeared but were printed and sent to subscribers when the set was complete. All volumes of the third edition are thus dated 1797.

The final page of each volume of the Encyclopædia Britannica contains "Directions" to the binder for the correct placement of the copperplates and maps. Nevertheless, some sets have the text and plates bound in separate volumes: the first 18 volumes containing the text, and volumes 19-20 the maps and copperplates.

Remove ads

Editors and contributors

Summarize

Perspective

Since Macfarquhar and Bell invited the editor of the first edition, William Smellie, to continue with the second edition, it is likely that they offered James Tytler, the editor of the second edition, to continue with the third. Certainly they retained him as a contributor. If in fact he worked as the third edition's editor, he did not do so for long, for he fled Edinburgh for northern England in 1788.[4]

By that point, if not earlier, Macfarquhar had taken over as editor. The preface names him the editor of volumes 1-12, up to "Mysteries." His editorship was cut short by his death at age 48, in 1793. His heirs were then bought out by Bell, who became sole owner of Britannica. Bell hired George Gleig, later the bishop of Brechin (consecrated on 30 October 1808), to carry on as editor for the remainder of the third edition. Gleig was annoyed to find that Macfarquhar had had not left an index of what had been covered and what was forthcoming. Two clergyman, James Thomson and James Walker, helped Gleig with the editing when he could not be in Edinburgh.[5] Gleig continued as editor for the 1801 Supplement.

All told, we know of thirty-five contributors to the third edition, fewer than the number of contributors to the Encyclopédie (1751–72), but more than the number of contributors to any previous English-language encyclopedia.[6] Many of the contributors are named in the anonymous preface, dated 1797 and apparently sent out with the title pages in that same year. In it, the author, undoubtedly Gleig, writes: "AEROLOGY, AEROSTATION, CHEMISTRY, ELECTRICITY, GUNNERY, HYDROSTATICS, MECHANICS, METEOROLOGY, with most of the separate articles in the various branches of natural history, we have reason to believe were compiled by Mr James Tytler chemist; a man who, though his conduct has been marked by almost perpetual imprudence, possesses no common share of science and genius."[7] According to the preface, Tytler's treatise on medicine for the second edition "was revised and improved for the present by Andrew Duncan, M.D. Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and Professor of the Institutes of Physic in the University." Tytler is also given some credit for "Motion," apparently co-written with Gleig.[8]

Among the editors of the third edition, Gleig was responsible for recruiting many but not all the contributors. He certainly contributed the most distinguished contributor, John Robison, a professor of natural philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. Robison, short of money, accepted a salary of a guinea a day for eight to ten hours of work. He ended up contributing more than twenty-five articles, some of them long ones: "Philosophy" (with Gleig), "Physics" (with Gleig), "Pneumatics," "Precession of the Equinoxes," "Projectiles," "Pump," "Resistance," "River," "Roof," "Rope-Making," "Rotation," "Seamanship," "Signals, Naval," "Simson (Dr. Robert)," "Sound," "Specific Gravity," "Statics," "Steam," "Steam-Engine," "Steel-Yard," "Stove," "Strength of Materials," "Telescope," perhaps "Thunder," "Tide," "Trumpet, Articulate," "Variation of the Compass," perhaps "Water," and "Works, Water."[9]

Remove ads

Contents

Summarize

Perspective

Dedication

The third edition began the tradition of dedicating the Britannica to the reigning British monarch, then King George III. Such dedications continued in the Britannica into the twenty-first century, albeit with shared dedications to the reigning British monarch and the reigning American president from the early twentieth-century onward. In the third edition, describing George III as "the Father of Your People, and enlightened Patron of Arts, Sciences and Literature," Gleig expressed his wish

THAT by the Wisdom of Your Councils, and the Vigour of Your Fleets and Armies, Your MAJESTY may be enabled soon to restore Peace to Europe; that You may again have leisure to extend Your Royal Care to the Improvement of Arts, and the Advancement of Knowledge; that You may Reign long over a Free, a Happy, and a Loyal People.[10]

In comparison with Ephraim Chambers' dedication of the Cyclopaedia (1728) to King George II, the dedication in the third edition reflected a growing spirit of nationalism common to encyclopedias' dedications in the second half of the eighteenth century.[11] The nationalistic rhetoric became much more pronounced in Gleig's dedication of the Supplement to the Third Edition in 1801:

In conducting to its conclusion the Encyclopaedia Britannica, I am conscious only of having been universally influenced by a sincere desire to do Justice to those Principles of Religion, Morality, and Social Order, of which the Maintenance constitutes the Glory of Your Majesty's Reign [....] The French Encyclopédie has been accused, and justly accused, of having disseminated, far and wide, the seeds of Anarchy and Atheism. If the Encyclopaedia Britannica shall, in any degree, counteract the tendency of that pestiferous Work, even these two Volumes will not be wholly unworthy of you Majesty's Patronage.[12]

Treatises

Like the previous two editions of the Britannica, the third edition was composed of a novel mixture of typographically distinct "treatises" (generally long) and normal articles in a single alphabetical sequence. Although the third edition was almost twice as long as the second edition, the number of treatises barely went up, from 72 to 88. Likewise, the proportion of the Britannica occupied by the treatises continued to decline, from 58% in the first edition to 32% in the second edition and 31% in the third edition. Four of the treatises in the third edition now counted more than 150 pages, setting new records for the Britannica: "Astronomy" (187 pages), "Chemistry" (262 pages), "Medicine" (310 pages), and "Pharmacy" (176 pages).[13]

In the first edition of the Britannica, William Smellie had touted the treatises as favoring self-education.[14] By the time of the third edition, they were proving useful in attracting eminent contributors to the Britannica. In principle, such contributors could communicate recent discoveries, and they sometimes took advantage of their treatises to drive home their own viewpoints.[15]

Tytler's ongoing influence

Many of the scientific articles in the third edition remained marked by Tytler's idiosyncratic viewpoints. His treatise "Electricity," an updated version of his treatise in the second edition, rejected Benjamin Franklin's conception of electricity as positive or negative. It was not an up-to-date representation of the subject, and it was denounced in one contemporary review: "A system so wild is not congenial to the usual accuracy of the Edinburgh writers." Still, the nineteenth-century physicist Michael Faraday later claimed to have drawn inspiration from this very treatise.[16]

In the second half of the alphabet especially, Robison attempted to correct Tytler's articles on scientific subjects, though without stating directly that he was taking aim at a fellow contributor.[17] Gleig came the closest to such an admission, writing in the preface that

[H]e [Gleig] took the opportunity, when he found any system [treatise] superficially treated, to supply its defects under some of the detached articles belonging to it. Of this he shall mention as one instance HYDROSTATICS; which, considered as a system, must be confessed to be defective; but he trusts that its defects are in a great measure supplied under the separate articles RESISTANCE of fluids, RIVER, SPECIFIC gravity, and Water-WORKS.[18]

The treatise "Hydrostatics," of course, had been written by Tytler, while Robison handled corrections in the other articles named in this passage.

Illustrations

The prospectus for the third edition had claimed that more than a hundred of the plates for the third edition would be newly engraved. Regardless, since Bell was a practical engraver rather than an artist, many if not all the plates were copied from elsewhere, whether from earlier editions of the Britannica or other sources. True to the prospectus, the third edition had more plates (about 540) than the first edition (160) or the second (340). Although it fell short of the standard set by the Encyclopédie, it was the most amply illustrated English-language encyclopedia to date.[19]

The third edition of the Britannica was the first one to appear with a frontispiece, though other British encyclopedias had had them since the early eighteenth century. The frontispiece, loosely modeled on Sébastien Le Clerc's engraving "L'Académie es sciences & des beaux arts" (1698), showed men and women engaging in intellectual pursuits in a setting of classical architecture. Unlike the similar frontispiece in Chambers' Cyclopaedia, this one showed a manned balloon floating in the sky - perhaps a salute to Tytler, an avid balloonist, but perhaps merely a sign of scientific and technological progress.[20]

Remarkably, many if not all sets of the third edition included color in one plate, the one illustrating the treatises "Acoustics" and "Aerostation," identified as "2nd plate II."[21] The plate was undoubtedly printed in black and white and then colored by hand.

Remove ads

Unauthorized editions

Summarize

Perspective

In addition to the legitimate sets printed in Edinburgh, unauthorized sets were being printed in Dublin by James Moore and Philadelphia by Thomas Dobson at almost the same time.

The first general American encyclopedia, entitled simply Encyclopaedia and often referred to as Dobson's Encyclopædia, was based almost entirely on the third edition of the Britannica. It was published at nearly the same time (1788–1798) as the original, together with an analogous supplement (1803), by the Scottish-American printer Thomas Dobson. Dobson, a master printer in printer when the first two editions of the Britannica were being produced there, relocated to the United States in 1783 or 1784.[22] The United States passed its first copyright law on 30 May 1790, but it did not protect foreign publications such as the Britannica. Unlicensed copying of the Britannica in the United States would remain a problem through the time of the ninth edition (1889).

Dobson first public announcement of his project was timed to coincide with George Washington's election as president. In this sense, the Encyclopaedia was meant as a celebration of the new political order and an attempt to bolster that order.[23] By June 1789, he had decided to drop the original title Encyclopaedia Britannica in favor of Encyclopaedia.[24] By at least 1790, Dobson was advertising new material in his encyclopedia. One consequence was the tendency of the Encyclopaedia "to praise all things American whenever opportunity arises."[25] Most importantly, he engaged Jedidiah Morse, the only known contributor, to work on geography. The mathematician and astronomer David Rittenhouse may also have contributed to "Astronomy."[26] In his Supplement to the third edition in 1803, Dobson brought in further American material, not only geographical articles on American places but also four new biographies, including biographies of Benjamin Franklin and George Washington. These biographies "helped differentiate Dobson's Supplement from the British version and to embed Morse's Federalist and conservative Congregationalist values within the text."[27]

Unauthorized sets of the third were also printed and sold in Dublin by James Moore under the title, Moore's Dublin Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica. Moore modified the contents of the Edinburgh edition less than Dobson did, but his edition nonetheless included changes, not only in the front matter but also in plates and at least seven articles. The articles on Dublin and Ireland, for example, were lengthened, and the timeline in "Chronology" was extended from 1783 to 1791.[28]

Remove ads

Supplement

Summarize

Perspective

After the death of Macfarquhar in 1793, Andrew Bell engaged in a multi-year dispute with Macfarquhar's trustees over ownership of the Britannica. In 1797, a year before the dispute ended with Bell taking full ownership of the Britannica, Gleig, who had long foreseen a supplement, was permitted to choose a new publisher. He settled on Bell's son-in-law Thomson Bonar.[29]

The two-volume Supplement to the Third Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica first appeared in 1801. It was reprinted in 1803 with minor revisions.[30] In both versions, the articles are ordered alphabetically and the volumes contain about 800 pages each.

Robison continued to as a contributor to the Supplement. In the preface, he is credited with nineteen articles, mostly on the subject of physics and engineering, and he ended up being the author of six of the eleven treatises in the Supplement.[31] So important was Robison's role that Gleig had come to consider him a co-editor by 1801. The two men bonded, in particular, over their hatred for the Jacobites and the French revolution, which notably emerged in the article "Guillotine" and its unsettling illustration.[32]

A new treatise on "Chemistry," 193 pages in length, was written by Thomas Thomson of Edinburgh. It was meant to supplant the even longer treatise in the main encyclopedia, written by Tytler and featuring a number of idiosyncratic ideas. Unlike most Britons, Thomson recognized the existence of an eighteenth-century chemical "revolution," and he used the newly invented French nomenclature throughout his treatise. He also wrote the treatises Mineralogy" and "Substances" for the Supplement.[33] Thomson went on to write the treatise "Chemistry" for the seventh edition of Britannica, forty years later.

Gleig, Robison, and Thomson, the main writers on scientific subjects in the Supplement, shared several assumptions. First, they rejected Tytler's treatment of science elsewhere in the third edition and sought to replace it. Second, they all presented science as concrete and practical. Third, they all thought of Isaac Newton's law of attraction in a general way, invoking it to explain other things besides gravitation.[34]

One widespread convention among contemporary encyclopedias was to delay any biographies until after a subject died.[35] Accordingly, most of the roughly 160 biographical entries in the Supplement were devoted to individuals who had died during or after the publication of the third edition, including George Washington. The longest biographical entry, at fifteen pages, was on the Jesuit natural philosopher Roger Joseph Boscovich.[36]

The two volumes of the Supplement contain fifty copperplates, none of them produced by Bell. Bonar retained sole ownership of the copyright to the Supplement. In the fourth edition of the Britannica, which Bell launched in 1801, perhaps out of "spiteful competition" with his alienated son-in-law Bonar, none of the material from the Supplement could be used in a direct way, as Bell did not have the copyright.[37] Bell died in 1809, and the fourth edition was completed the next year. Upon his death, one of major distributors of the Britannica, Archibald Constable, bought the rights to the Britannica as well as Bonar's rights to the Supplement by making him a partial owner.[38]

Remove ads

Sales and influence

Summarize

Perspective

In Edinburgh, 10,000 or 13,000 sets were printed, according to Robert Kerr[39] and Archibald Constable,[40] respectively. In addition, several thousand sets of the Supplement to the Third Edition were probably sold[41] as well as several hundred copies of Dobson's re-edition[42] and more than a thousand of Moore's.[43] These sales far outdid those of the first and second editions, and the third edition earned Bell and Macfarquhar a net profit of 42,000 pounds in addition to their stipends for printing and engraving.[44]

Just as importantly, the third edition of the Britannica was the first one to be a resounding critical success.[45] In this sense, it established the Britannica as an authoritative work of reference for much of the next two centuries. It also became strongly associated with Britishness, in part because of its sometimes patriotic and anti-French tenor. One anecdote has it that in 1797, Fath Ali Shah was given a complete set of the third edition, which he "immediately sat down to read [...] from cover to cover, from beginning to end," after which he extended his royal title to include "Most Formidable Lord and Master of the Encyclopædia Britannica."[46] This is probably fictional, for, among other things, Fath Ali Shah was only starting to familiarize himself with things British in 1799.[47] Yet the third edition traveled abroad, and it was loaned by a British military officer to the Burmese king Baba Sheen.[48]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads