Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Faction fighting in Ireland

Organised mass brawling in rural Ireland From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Faction fighting was a form of organised mass brawling between rival groups, or factions, that occurred primarily in rural Ireland during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These confrontations typically took place at public gatherings such as fairs, pattern days, weddings, and funerals. Faction fights often involved large numbers of participants armed with sticks, most notably the traditional shillelagh, as well as stones and other improvised weapons.[1][2]: 29–34 [3]: 513–514

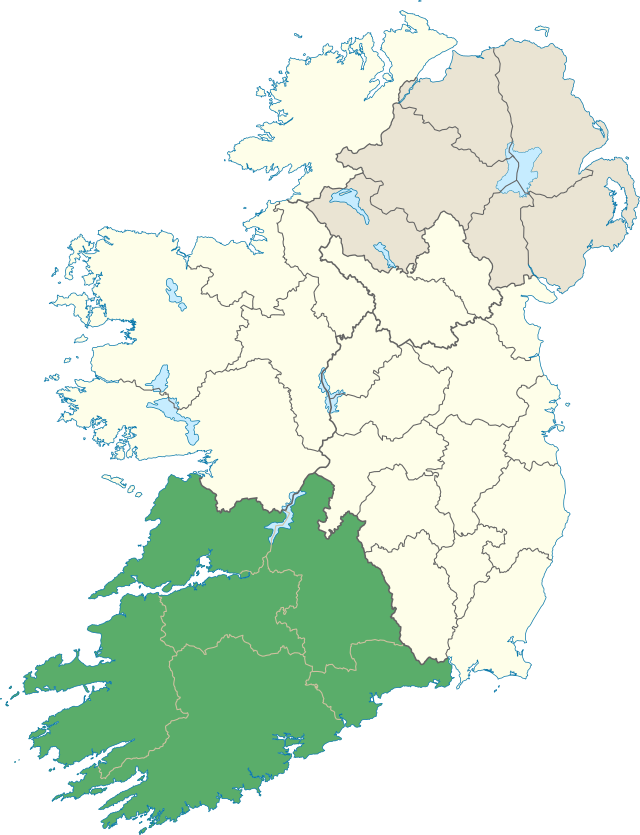

The practice developed in a society under British rule, where local policing was weak and often distrusted and agrarian tensions over land and rent were common.[2]: 30 It was closely associated with the traditional Irish stick-fighting art of bataireacht (Irish for beating with a club)[4] and was often rooted in local, class-based, or political rivalries.[3]: 515–516 Faction groups frequently developed distinctive names, leadership hierarchies, and battle cries. Some large-scale rivalries, especially in Munster, spread across multiple counties during the early nineteenth century.[2]: 35–37

Remove ads

Historical background

Rural Irish society in this period was dominated by an Anglo-Irish landlord class, and disputes over rent and tenure were widespread, especially as population growth and changing landholding patterns created large numbers of landless labourers and cottiers.[2]: 17–20 Formal courts were often inaccessible or distrusted, prompting some communities to rely on collective displays of strength to defend local interests.[2]: 23–24 [3]: 525 Agrarian protest was also linked to wider political and religious grievances as well as local disputes.[3]: 521 The traditional combat style of bataireacht provided an established method of fighting and readily available weapons, particularly the shillelagh, while seasonal festivals and pattern days created occasions for rival groups to confront one another.[3]: 518–520

Remove ads

Women and faction fighting

Although faction fighting was primarily a male activity, women sometimes played significant supporting roles. Contemporary reports and later sources describe women urging male relatives to fight, acting as messengers, and occasionally joining the violence themselves.[5]: 803–804 Their presence at fairs and pattern days could reinforce family and community loyalties and sometimes escalate confrontations.[2]: 43–44

Remove ads

Notable factions

Distinct local factions emerged during the height of Irish faction fighting, often developing strong identities and long-running rivalries. The most prominent and extensively documented were the 'Caravats' and the 'Shanavests', who fought across Munster in the early nineteenth century, particularly in the counties of Tipperary, Limerick, Cork and Waterford.The Caravats drew support mainly from cottiers and landless labourers, while the Shanavests were associated with better-off leaseholding farmers.[2]: 66–67 Their clashes were often large and sometimes deadly, drawing hundreds of combatants and attracting the attention of local authorities.

The factions’ exact origins are uncertain. Contemporary observers and later historians have connected them to agrarian tensions in areas with insecure landholding and sharp class divisions between small farmers, labourers, and better-off tenants.[2]: 36–37 While some early encounters grew out of local disputes, the rivalry soon became a recurring feature of public gatherings such as fairs and pattern days.[3]: 516

Decline

Summarize

Perspective

Faction fighting in Ireland declined over the course of the nineteenth century as political, religious, and social conditions changed. Large-scale political mobilisation offered new outlets for collective display and competition. During the Catholic Emancipation campaign of 1828, mass demonstrations attracted participants who might previously have joined violent gatherings, redirecting communal energies into politics.[3]: 513–514, 526

Moral reform movements and local authorities also sought to control unruly fairs and pattern days, which had been traditional venues for fights. The suppression of Donnybrook Fair in 1855 was a prominent example of efforts to regulate public leisure and reduce opportunities for mass violence.[6]: 9–11, 18–19

Broader social changes also contributed to the decline. Population collapse and emigration following the Great Famine (Irish an Gorta Mór) of the 1840s weakened the rural networks that had supported faction fighting. Ideas of respectability and recreation promoted by the Catholic Church and local elites reduced support for violent pastimes. The expansion of the Royal Irish Constabulary and a more effective legal system made large gatherings increasingly subject to official suppression, and levels of interpersonal violence fell in the later nineteenth century.[7]: 57–59 Leisure activities also became more regulated and commercialised, reducing the role of faction fighting in rural festive life.[7]: 66–68

Remove ads

Legacy and cultural memory

Elements of faction fighting have been remembered in Irish folklore. Recordings in the Irish Folklore Commission's "School's Collection" includes some stories of notable fights.[8] In her memoir Peig (1936), storyteller Peig Sayers recalled the social prestige once attached to faction leaders: "It was common at the time for people to be in contention with each other… A man was no use without a party of hard men to back him up. A man whom a faction followed would be sooner received than great wealth with a man who had nobody behind him".[9] Historians of the Gaelic Athletic Association note that early GAA clubs adopted the colours or symbols once associated with local fighting factions, carrying older community rivalries into a new sporting context allowing traces of these identities to persist into the late nineteenth century.[10] Hurling, once associated with violent brawls and occasionally used as cover for agrarian protest in the pre-Famine period, was later formalised and structured by the newly founded GAA, which helped replace earlier unruly gatherings with organised sport.[11]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads