Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

The Loves of the Gods

Fresco by Annibale Carracci From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

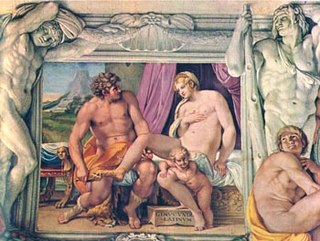

The Loves of the Gods is a monumental fresco cycle, completed by the Bolognese artist Annibale Carracci and his studio, in the Farnese Gallery which is located in the west wing of the Palazzo Farnese, now the French Embassy, in Rome. The frescoes were greatly admired at the time, and were later considered to reflect a significant change in painting style away from sixteenth century Mannerism in anticipation of the development of Baroque and Classicism in Rome during the seventeenth century.

Remove ads

Production

Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, Pope Paul III's great-great-grandson, commissioned Annibale Carracci and his workshop to decorate the barrel-vaulted gallery on the piano nobile of the family palace. Work was started in 1597 and was not entirely finished until 1608, one year before Annibale's death.[1] His brother Agostino joined him from 1597 to 1600, and other artists in the workshop included Giovanni Lanfranco, Francesco Albani, Domenichino, and Sisto Badalocchio.

Remove ads

Scheme and interpretations

Summarize

Perspective

Annibale Carracci had first decorated a small room, the Camerino (1595–1597), with scenes from the life of Hercules. The Herculean theme was probably selected because the Farnese Hercules was standing at the time in the Palazzo Farnese.[citation needed] This concept of art imitating ancient art seems to have been carried over to the large Gallery. While performing graduate research on the Gallery, Thomas Hoving, later director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, pointed out many correspondences between the frescoes and items in the famous Farnese Collection of Roman sculpture. Much of the collection is now housed in the Capodimonte Museum and National Archaeological Museum in Naples but, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it was arranged according to themes within the Palazzo Farnese. Hoving's suggestion that many details of the frescoes were designed to complement the marbles below has been generally accepted.[2]

In 1597, Carracci began to decorate the Gallery with scenes depicting the loves of the gods set within frames (quadri riportati) and faux bronze medallions painted on an illusionistic architectural framework referred to as quadratura. Ignudi, putti, satyrs, grotesques, and standing Atlas figures (Atlantes) help support the painted framework.

Gian Pietro Bellori, a biographer of seventeenth-century artists and Platonic apologist, called the cycle "Human Love Governed by Celestial Love". This observation was based principally on Carracci's depiction of putti representing Cupid (equated by Bellori with profane love) and Anteros (equated with sacred love) found at the four corners of the vault. For example, Bellori writes:[3]

The painter wished to represent with various symbols the war and peace between heavenly and common love formulated by Plato. On one side he painted Heavenly Love wrestling with Common Love and pulling him by the hair: this is the philosophy and most sacred law that removes the soul from vice, raising it on high. Accordingly, a crown of immortal laurel is resplendent overhead amid brilliant light, demonstrating that victory over the irrational appetites raises men up to heaven.

Hoving saw it differently. In his memoir, he writes:[2]

My lucky discovery destroyed the accepted interpretation of Annibale's fresco cycle as a "Neo-Platonic visual essay about celestial love's supremacy over physical passion." The paintings were actually both an entertaining celebration of a bunch of randy Olympians hitting on each other and also an up-scale mind game paying homage to Odoardo's fine antiquities collection.

Remove ads

Scenes on the vault

Summarize

Perspective

In addition to the putti shown at the four corners, The Loves of the Gods are depicted on the vault in thirteen narrative scenes. Complementing them, there are twelve medallions painted to appear as bronze reliefs. These medallions portray additional stories of love, abduction, and tragedy. The scenes are arranged as follows:

- Central row (from left to right in the accompanying image): Pan and Diana, The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne, and Mercury and Paris.

Beginning in the lower left and proceeding counter-clockwise around the vault, the remaining scenes are:

- West side (from left to right in the lower portion of the accompanying image): Jupiter and Juno, Marine scene (traditionally The Triumph of Galatea), and Diana and Endymion.

- Medallions on the west side (from left to right): Apollo and Marsyas, Boreas and Orithyia, Orpheus and Euridice, and The Rape of Europa.

- South side (on the right of the accompanying image): Apollo and Hyacinth above Polyphemus and Galatea.

- Medallions on the south side: Possible scene of abduction and Jason and the Golden Fleece.

- East side (from right to left in the upper portion of the accompanying image): Hercules and Iole, Aurora and Cephalus, and Venus and Anchises.

- Medallions on the east side (from right to left): Hero and Leander, Pan and Syrinx, Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, and Cupid and Pan.

- North side (on the left of the accompanying image): The Rape of Ganymede above Polyphemus and Acis.

- Medallions on the north side: Judgement of Paris and Pan and Apollo.

The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne

Prominently displayed in the center panel, the Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne depicts a both riotous and classically restrained procession which ferries Bacchus and Ariadne to their lovers' bed. Here, the underlying myth is that Bacchus, the god of wine, had gained the love of the abandoned princess, Ariadne. The procession recalls the triumphs of the Republican and Imperial Roman era, in which the parades of victorious leaders had the laurel-crowned 'imperator' in a white chariot with two white horses. In Carracci's procession, the two lovers are seated in chariots drawn by tigers[4] and goats, and accompanied by a parade of nymphs, bacchanti, and trumpeting satyrs. At the fore, Bacchus' tutor, the paunchy, ugly, and leering drunk Silenus, rides an ass. The figures carefully cavort in order to hide most naked male genitals.[5]

The program refers to Ovid's Metamorphoses (VIII; lines 160–182) and the spirit alludes to contemporary images voiced, for example, in a carnival song-poem written by Lorenzo de' Medici in about 1475, that entreats:[6]

Quest'è Bacco ed Arïanna,

belli, e l'un de l'altro ardenti:

perché 'l tempo fugge e inganna,

sempre insieme stan contenti.

Queste ninfe ed altre genti

sono allegre tuttavia.

Chi vuol esser lieto, sia:

di doman non c'è certezza.Here are Bacchus and Ariadne,

Handsome, and burning for each other:

Because time flees and fools,

They stay together always content.

These nymphs and those others

Are ever full of joy.

Let those who wish to be happy, be:

Of tomorrow, we have no certainty.

Additional scenes

Remove ads

Scenes on the walls

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Annibale Carracci's decorations in the Farnese Gallery demonstrated a new grand manner of monumental fresco painting.[11] They exerted a powerful formative influence on both canvas and fresco painting in Rome during the seventeenth century. The dual classicizing and baroque tendencies in this work would fuel the debate by the next generation of fresco painters, between Sacchi and Pietro da Cortona, over the number of figures to be included in a painting.[12] Carracci's treatment of the composition and the disposition and expression of the figures would influence painters such as Sacchi and Poussin, whereas his effervescent narrative manner influenced Cortona.

Annibale Carracci, in his day, was seen as one of the key painters to revive the classical style. In contrast, a few years later, artists such as Caravaggio and his followers would rebel against representing spatial depth in colour and light, and introduce tenebrous dramatic realism into their art instead. But it would be inappropriate to view Annibale Carracci as solely the continuation of an inherited tradition; in his day, his vigorous and dynamic style, and that of his studio assistants, changed the pre-eminent style of painting in Rome. His work would have been seen as liberating for artists of his day, touching on pagan themes with an unconstrained joy. It could be said that while Mannerism had mastered the art of formal strained contraposto and contorsion; Annibale Carracci had depicted dance and joy.

Later followers of Neoclassic formalism and severity frowned on the excesses of Annibale Carracci, but in his day, he would have been seen as masterful in achieving the supreme approximation to classic beauty in the tradition of Raphael and Giulio Romano's secular frescoes in the Loggia of the Villa Farnesina.[13] Unlike Raphael, though, his figures can display a Michelangelo-esque muscularity, and depart from the often emotionless visages of High Renaissance painting.[14]

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads