Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Ordinal number

Generalization of "n-th" to infinite cases From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

In set theory, an ordinal number, or ordinal, is a generalization of ordinal numerals (first, second, nth, etc.) aimed to extend enumeration to infinite sets.[1]

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A finite set can be enumerated by successively labeling each element with the least natural number that has not been previously used. To extend this process to various infinite sets, ordinal numbers are defined more generally using linearly ordered Greek letter variables that include the natural numbers and have the property that every set of ordinals has a least or "smallest" element (this is needed for giving a meaning to "the least unused element"). This more general definition allows us to define an ordinal number (omega) to be the least element that is greater than every natural number, along with ordinal numbers , , etc., which are even greater than .

A linear order such that every non-empty subset has a least element is called a well-order. The axiom of choice implies that every set can be well-ordered, and given two well-ordered sets, one is isomorphic to an initial segment of the other. So ordinal numbers exist and are essentially unique.

Ordinal numbers are distinct from cardinal numbers, which measure the size of sets. Although the distinction between ordinals and cardinals is not this apparent on finite sets (one can go from one to the other just by counting labels), they are very different in the infinite case, where different infinite ordinals can correspond to sets having the same cardinal. Like other kinds of numbers, ordinals can be added, multiplied, and exponentiated, although none of these operations are commutative.

Ordinals were introduced by Georg Cantor in 1883[2] to accommodate infinite sequences and classify derived sets, which he had previously introduced in 1872 while studying the uniqueness of trigonometric series.[3]

Remove ads

Ordinals extend the natural numbers

Summarize

Perspective

A natural number (which, in this context, includes the number 0) can be used for two purposes: to describe the size of a set, or to describe the position of an element in a sequence. When restricted to finite sets, these two concepts coincide, since all linear orders of a finite set are isomorphic.

However, for infinite sets, one has to distinguish between the notion of size, which leads to cardinal numbers, and the notion of position, which leads to the ordinal numbers described here. This is because while any set has only one size (its cardinality), there are many nonisomorphic well-orderings of any infinite set, as explained below.

Whereas the notion of cardinal number is associated with a set with no particular structure on it, the ordinals are intimately linked with the special kind of sets that are called well-ordered. A well-ordered set is a totally ordered set (an ordered set such that, given two distinct elements, one is less than the other) in which every non-empty subset has a least element. Equivalently, assuming the axiom of dependent choice, it is a totally ordered set without any infinite decreasing sequence — though there may be infinite increasing sequences. Ordinals may be used to label the elements of any given well-ordered set (the smallest element being labelled 0, the one after that 1, the next one 2, "and so on"), and to measure the "length" of the whole set by the least ordinal that is not a label for an element of the set. This "length" is called the order type of the set.

Every ordinal is defined by the set of ordinals that precede it. The most common definition of ordinals identifies each ordinal as the set of ordinals that precede it. For example, the ordinal 42 is generally identified as the set {0, 1, 2, ..., 41}. Conversely, any set S of ordinals that is downward closed — meaning that for every ordinal α in S and every ordinal β < α, β is also in S — is (or can be identified with) an ordinal.

This definition of ordinals in terms of sets allows for infinite ordinals. The smallest infinite ordinal is , which can be identified with the set of natural numbers (so that the ordinal associated with any natural number precedes ). Indeed, the set of natural numbers is well-ordered—as is any set of ordinals—and since it is downward closed, it can be identified with the ordinal associated with it.

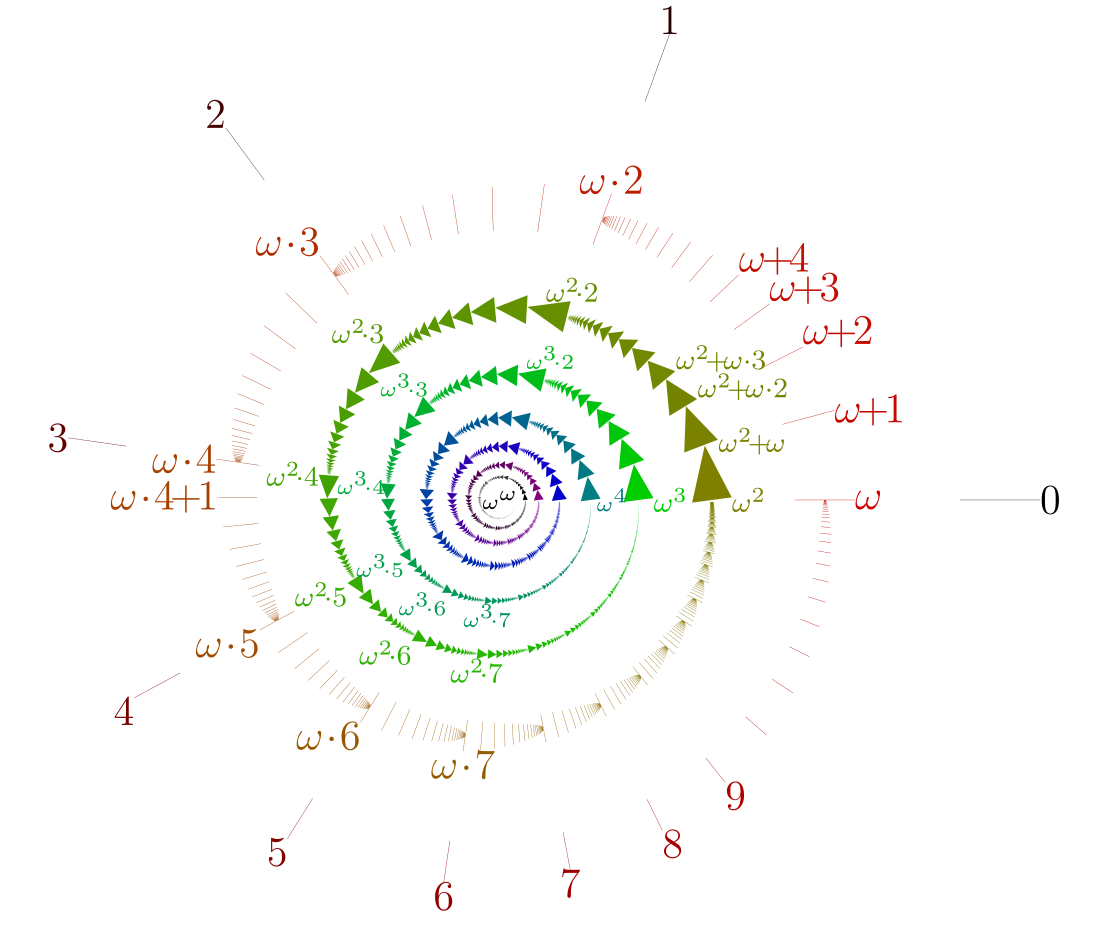

Perhaps a clearer intuition of ordinals can be formed by examining a first few of them: as mentioned above, they start with the natural numbers, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ... After all natural numbers comes the first infinite ordinal, ω, and after that come ω+1, ω+2, ω+3, and so on. (Exactly what addition means will be defined later on: just consider them as names.) After all of these come ω·2 (which is ω+ω), ω·2+1, ω·2+2, and so on, then ω·3, and then later on ω·4. Now the set of ordinals formed in this way (the ω·m+n, where m and n are natural numbers) must itself have an ordinal associated with it, and that is ω2. Further on, there will be ω3, then ω4, and so on, and ωω, then ωωω, then later ωωωω, and even later ε0 (epsilon nought) (to give a few examples of relatively small—countable—ordinals). This can be continued indefinitely (as every time one says "and so on" when enumerating ordinals, it defines a larger ordinal). The smallest uncountable ordinal is the set of all countable ordinals, expressed as ω1 or .[4]

Remove ads

Definitions

Summarize

Perspective

Well-ordered sets

In a well-ordered set, every non-empty subset contains a distinct smallest element. Given the axiom of dependent choice, this is equivalent to saying that the set is totally ordered and there is no infinite decreasing sequence (the latter being easier to visualize). In practice, the importance of well-ordering is justified by the possibility of applying transfinite induction, which says, essentially, that any property that passes on from the predecessors of an element to that element itself must be true of all elements (of the given well-ordered set). If the states of a computation (computer program or game) can be well-ordered—in such a way that each step is followed by a "lower" step—then the computation will terminate.

It is inappropriate to distinguish between two well-ordered sets if they only differ in the "labeling of their elements", or more formally: if the elements of the first set can be paired off with the elements of the second set such that if one element is smaller than another in the first set, then the partner of the first element is smaller than the partner of the second element in the second set, and vice versa. Such a one-to-one correspondence is called an order isomorphism, and the two well-ordered sets are said to be order-isomorphic or similar (with the understanding that this is an equivalence relation).

Formally, if a partial order ≤ is defined on the set S, and a partial order ≤' is defined on the set S' , then the posets (S,≤) and (S' ,≤') are order isomorphic if there is a bijection f that preserves the ordering. That is, f(a) ≤' f(b) if and only if a ≤ b. Provided there exists an order isomorphism between two well-ordered sets, the order isomorphism is unique: this makes it quite justifiable to consider the two sets as essentially identical, and to seek a "canonical" representative of the isomorphism type (class). This is exactly what the ordinals provide, and it also provides a canonical labeling of the elements of any well-ordered set. Every well-ordered set (S,<) is order-isomorphic to the set of ordinals less than one specific ordinal number under their natural ordering. This canonical set is the order type of (S,<).

Essentially, an ordinal is intended to be defined as an isomorphism class of well-ordered sets: that is, as an equivalence class for the equivalence relation of "being order-isomorphic". There is a technical difficulty involved, however, in the fact that the equivalence class is too large to be a set in the usual Zermelo–Fraenkel (ZF) formalization of set theory. But this is not a serious difficulty. The ordinal can be said to be the order type of any set in the class.

Definition of an ordinal as an equivalence class

The original definition of ordinal numbers, found for example in the Principia Mathematica, defines the order type of a well-ordering as the set of all well-orderings similar (order-isomorphic) to that well-ordering: in other words, an ordinal number is genuinely an equivalence class of well-ordered sets. This definition must be abandoned in ZF and related systems of axiomatic set theory because these equivalence classes are too large to form a set. However, this definition still can be used in type theory and in Quine's axiomatic set theory New Foundations and related systems (where it affords a rather surprising alternative solution to the Burali-Forti paradox of the largest ordinal).

Remove ads

Von Neumann definition of ordinals

A von Neumann ordinal is defined as a set that represents a well-ordered class by being the set of all preceding ordinals. Formally, a set is an ordinal if and only if is transitive (every element of is a subset of ) and strictly well-ordered by set membership (). Assuming the Axiom of regularity, a set is an ordinal if and only if it is transitive and strictly totally ordered by membership, as regularity prevents infinite descending chains. Without assuming regularity, the definition requires explicit well-ordering: membership must be trichotomous on and every non-empty subset must have a minimal element. These conditions imply that membership is irreflexive () and transitive. The finite ordinals are defined inductively as , , , and so on.

Basic properties

- 0 = ∅ is an ordinal.

- If α ∈ β and β is an ordinal, then α is an ordinal: transitivity is found by unpacking the definition of ordinal. In particular, transitivity of α as a set is found by finding that all the relevant ordinals are elements of β and then using the transitivity of the ∈ relation within β.[5]

- If α ≠ β are both ordinals and α ⊂ β, then α ∈ β: let γ = min{β − α}. α is transitive so α = { ξ ∈ β | ξ ∈ γ } = γ ∈ β.[6]. Note: this means that ⊂ is essentially the ≤ relation between ordinals.

- If α and β are both ordinals, then α ⊂ β or β ⊂ α: γ = α ∩ β is an ordinal, so γ = α or γ = β, or else by (iii) γ ∈ γ, contradicting irreflexively.[7]

- Any nonempty class of ordinals is a well-ordered class; if it is a set, then it is a well-ordered set.

- If A is a nonempty set of ordinals, then .[8]

- If A is a set of ordinals, then is an ordinal.[9]

- For any ordinal α, succ α = α ∪ {α} is an ordinal and succ α = min{β : β > α}.[10]

- (Burali-Forti paradox) The class of all ordinals is not a set, otherwise consider succ sup ON.[11]

Natural numbers and order types

The set of natural numbers is defined as the smallest inductive set (containing and closed under successor). It is an ordinal because induction demonstrates it is a transitive set composed of ordinals, which implies that the union of is equal to , and the above theorems imply that this implies that is an ordinal. is the least limit ordinal (see following section on limit and successor ordinals), meaning it is a non-zero ordinal with no immediate predecessor because induction also demonstrates that all elements of are zero or a successor.

Every well-ordered set is order-isomorphic to exactly one ordinal, known as its order type. Uniqueness is guaranteed because a well-ordered set cannot be isomorphic to a proper initial segment of itself, preventing isomorphism to two distinct ordinals. The existence of this ordinal is proven by defining a map pairing each with the ordinal representing the order type of the initial segment . By the Axiom schema of replacement, the range of this map is a set of ordinals. Because this range is downward closed (the order type of a segment of a segment is a smaller ordinal), the range is itself an ordinal . The domain of the isomorphism must be all of ; otherwise, the least element outside the domain would imply , which would effectively include in the domain, a contradiction. Thus, .

Remove ads

Successor and limit ordinals

Summarize

Perspective

Every ordinal number is one of three types: the ordinal zero, a successor ordinal, or a limit ordinal.

- Zero: The ordinal is the least ordinal.

- Successor ordinals: An ordinal is a successor if for some ordinal . In this case, is the maximum element of .

- Limit ordinals: An ordinal is a limit ordinal if and is not a successor ordinal.

There is variation in the definition of limit ordinals regarding the inclusion of zero. Some texts, such as Introduction to Cardinal Arithmetic by Holz et al., define a limit ordinal as a non-zero ordinal that is not a successor.[12] In contrast, other standard set theory texts, including Jech's Set Theory and Just and Weese's Discovering Modern Set Theory, define a limit ordinal simply as any ordinal that is not a successor, which implies that 0 is a limit ordinal.[13][14] When the topological definition is used (based on the order topology), 0 is not a limit ordinal because it is not a limit point of the set of smaller ordinals (which is empty); Rosenstein's Linear Orderings uses this definition.[15] When 0 is included as a limit, ordinals that are strictly greater than 0 and not successors are usually referred to as "nonzero limit ordinals".

The following properties characterize nonzero limit ordinals:

- is a nonzero limit ordinal if and only if and for every ordinal , the successor is also less than .

This implies that a nonzero limit ordinal is equal to the supremum of all ordinals strictly less than it:

- is a nonzero limit ordinal if and only if and .

For example, is a limit ordinal because any natural number is less than , and the successor of any natural number is also a natural number (hence less than ).

Remove ads

Transfinite sequence

If is any ordinal and is a set, an -indexed sequence of elements of is a function from to . This concept, a transfinite sequence (if is infinite) or ordinal-indexed sequence, is a generalization of the concept of a sequence. An ordinary sequence corresponds to the case , while a finite corresponds to a tuple, a.k.a. string.

While a sequence indexed by a specific ordinal is a set, a sequence indexed by the class of all ordinals is a proper class. The Axiom schema of replacement guarantees that any initial segment of such a class-sequence (the restriction of the function to some specific ordinal ) is a set.

When is a transfinite sequence of ordinals indexed by a limit ordinal and the sequence is increasing (i.e. ), its limit is defined as the least upper bound of the set .

A transfinite sequence mapping ordinals to ordinals is said to be continuous (in the order topology) if for every limit ordinal in its domain and every ε < max (1, f (λ)) there exists a δ < λ such that for every γ, δ < γ < λ implies ε ≤ f (γ) ≤ f (λ). A sequence is called normal if it is both strictly increasing and continuous. If a sequence f is increasing (not necessarily strictly) and continuous and λ is a limit ordinal, then .

Remove ads

Transfinite induction

Summarize

Perspective

Transfinite induction holds in any well-ordered set, but it is so important in relation to ordinals that it is worth restating here.

- Any property that passes from the set of ordinals smaller than a given ordinal α to α itself, is true of all ordinals.

That is, if P(α) is true whenever P(β) is true for all β < α, then P(α) is true for all α. Or, more practically: in order to prove a property P for all ordinals α, one can assume that it is already known for all smaller β < α.

Transfinite recursion

Transfinite induction can be used not only to prove theorems but also to define functions on ordinals. This is known as transfinite recursion.

Formally, a function F is defined on the ordinals if, for every ordinal α, the value is specified using the set of values .

Very often, when defining a function F by transfinite recursion on all ordinals, the definition is separated into cases based on the type of the ordinal:

- Base case: Define .

- Successor step: Define assuming is defined.

- Limit step: For a limit ordinal , define as the limit of for all (either in the sense of ordinal limits or some other notion of limit if the codomain allows it).

The interesting step in the definition is usually the successor step. If for limit ordinals is defined as the limit of for (and takes ordinal values and is non-decreasing), the function is said to be continuous. Ordinal addition, multiplication and exponentiation are continuous as functions of their second argument.

The existence and uniqueness of such a function are proven by constructing it as the union of partial approximations. The proof proceeds in three steps:

- Local Existence: For any specific ordinal δ, one proves the existence of a unique "recursion segment"—a function defined on δ that satisfies the recursive rule for all .

- Uniqueness and Compatibility: One proves that any two recursion segments agree on their common domain. If is a segment on and is a segment on with , then restricted to is identical to .

- Global Definition: The global class function F is defined as the union of all such unique recursion segments. For any ordinal α, the value is the value assigned to α by any recursion segment defined on a domain larger than α.

The rigorous justification for local existence relies on the Axiom schema of replacement on the step of limit ordinals in order to collect the recursion segments into a set.

This construction allows definitions such as ordinal addition, multiplication, and exponentiation to be rigorous. For example, exponentiation is defined recursively on β:

- (for successor ordinals)

- (for limit ordinals λ)

The principle of transfinite recursion also implies that recursion can be performed up to a specific ordinal (defining a set rather than a proper class). This is formally achieved by defining a rule that returns a "throwaway" or default value (such as 0) if the recursion index exceeds . This technique is often used to define sequences of length . For example, to prove that a normal function has arbitrarily large fixed points, one constructs a sequence starting with any ordinal and defines by recursion on . The limit is a fixed point of because continuity ensures .

Indexing classes of ordinals

Any well-ordered set is similar (order-isomorphic) to a unique ordinal number ; in other words, its elements can be indexed in increasing fashion by the ordinals less than . This applies, in particular, to any set of ordinals: any set of ordinals is naturally indexed by the ordinals less than some . The same holds, with a slight modification, for classes of ordinals (a collection of ordinals, possibly too large to form a set, defined by some property): any class of ordinals can be indexed by ordinals (and, when the class is unbounded in the class of all ordinals, this puts it in class-bijection with the class of all ordinals). So the -th element in the class (with the convention that the "0-th" is the smallest, the "1-st" is the next smallest, and so on) can be freely spoken of. Formally, the definition is by transfinite induction: the -th element of the class is defined (provided it has already been defined for all ), as the smallest element greater than the -th element for all .

This could be applied, for example, to the class of limit ordinals: the -th ordinal, which is either a limit or zero is (see ordinal arithmetic for the definition of multiplication of ordinals). Similarly, one can consider additively indecomposable ordinals (meaning a nonzero ordinal that is not the sum of two strictly smaller ordinals): the -th additively indecomposable ordinal is indexed as . The technique of indexing classes of ordinals is often useful in the context of fixed points: for example, the -th ordinal such that is written . These are called the "epsilon numbers".

Remove ads

Arithmetic of ordinals

There are three usual operations on ordinals: addition, multiplication, and exponentiation. Each can be defined in essentially two different ways: either by constructing an explicit well-ordered set that represents the operation or by using transfinite recursion. The Cantor normal form provides a standardized way of writing ordinals. It uniquely represents each ordinal as a finite sum of ordinal powers of ω. However, this cannot form the basis of a universal ordinal notation due to such self-referential representations as ε0 = ωε0.

Ordinals are a subclass of the class of surreal numbers, and the so-called "natural" arithmetical operations for surreal numbers are an alternative way to combine ordinals arithmetically. They retain commutativity at the expense of continuity.

Interpreted as nimbers, a game-theoretic variant of numbers, ordinals can also be combined via nimber arithmetic operations. These operations are commutative but the restriction to natural numbers is generally not the same as ordinary addition of natural numbers.

Remove ads

Ordinals and cardinals

Summarize

Perspective

Initial ordinal of a cardinal

Each ordinal associates with one cardinal, its cardinality. If there is a bijection between two ordinals (e.g. ω = 1 + ω and ω + 1 > ω), then they associate with the same cardinal. Any well-ordered set having an ordinal as its order-type has the same cardinality as that ordinal. The least ordinal associated with a given cardinal is called the initial ordinal of that cardinal. Every finite ordinal (natural number) is initial, and no other ordinal associates with its cardinal. But most infinite ordinals are not initial, as many infinite ordinals associate with the same cardinal. The axiom of choice is equivalent to the statement that every set can be well-ordered, i.e. that every cardinal has an initial ordinal. In theories with the axiom of choice, the cardinal number of any set has an initial ordinal, and one may employ the Von Neumann cardinal assignment as the cardinal's representation. (However, we must then be careful to distinguish between cardinal arithmetic and ordinal arithmetic.) In set theories without the axiom of choice, a cardinal may be represented by the set of sets with that cardinality having minimal rank (see Scott's trick).

One issue with Scott's trick is that it identifies the cardinal number with , which in some formulations is the ordinal number . It may be clearer to apply Von Neumann cardinal assignment to finite cases and to use Scott's trick for sets which are infinite or do not admit well orderings. Note that cardinal and ordinal arithmetic agree for finite numbers.

The α-th infinite initial ordinal is written , it is always a limit ordinal. Its cardinality is written . For example, the cardinality of ω0 = ω is , which is also the cardinality of ω2 or ε0 (all are countable ordinals). So ω can be identified with , except that the notation is used when writing cardinals, and ω when writing ordinals (this is important since, for example, = whereas ). Also, is the smallest uncountable ordinal (to see that it exists, consider the set of equivalence classes of well-orderings of the natural numbers: each such well-ordering defines a countable ordinal, and is the order type of that set), is the smallest ordinal whose cardinality is greater than , and so on, and is the limit of the for natural numbers n (any limit of cardinals is a cardinal, so this limit is indeed the first cardinal after all the ).

Cofinality

The cofinality of an ordinal is the smallest ordinal that is the order type of a cofinal subset of . Notice that a number of authors define cofinality or use it only for limit ordinals. The cofinality of a set of ordinals or any other well-ordered set is the cofinality of the order type of that set.

Thus for a limit ordinal, there exists a -indexed strictly increasing sequence with limit . For example, the cofinality of ω2 is ω, because the sequence ω·m (where m ranges over the natural numbers) tends to ω2; but, more generally, any countable limit ordinal has cofinality ω. An uncountable limit ordinal may have either cofinality ω as does or an uncountable cofinality.

The cofinality of 0 is 0. And the cofinality of any successor ordinal is 1. The cofinality of any limit ordinal is at least .

An ordinal that is equal to its cofinality is called regular and it is always an initial ordinal. Any limit of regular ordinals is a limit of initial ordinals and thus is also initial even if it is not regular, which it usually is not. If the Axiom of Choice, then is regular for each α. In this case, the ordinals 0, 1, , , and are regular, whereas 2, 3, , and ωω·2 are initial ordinals that are not regular.

The cofinality of any ordinal α is a regular ordinal, i.e. the cofinality of the cofinality of α is the same as the cofinality of α. So the cofinality operation is idempotent.

Closed unbounded sets and classes

The concepts of closed and unbounded sets are typically formulated for subsets of a regular cardinal that is uncountable. A subset is said to be unbounded (or cofinal) in if for every ordinal , there exists some such that . To define the property of being closed, one first defines a limit point: a non-zero ordinal is a limit point of if . The set is closed in if it contains all of its limit points below . A set that is both closed and unbounded is commonly referred to as a club set.

Examples of club sets are fundamental to set theory. The set of all limit ordinals less than is a club set, as there is always a limit ordinal greater than any given ordinal below , and a limit of limit ordinals is itself a limit ordinal. If is a limit cardinal, the set of all cardinals below is unbounded, and its set of limit points—the limit cardinals—forms a closed unbounded set. Furthermore, if is a strong limit cardinal (such as an inaccessible cardinal), the set of strong limit cardinals below is also a club set. Another significant example arises from normal functions (functions that are strictly increasing and continuous); the range of any normal function is a closed unbounded subset of .

Club sets possess structural properties that allow them to generate a filter. Because is regular and uncountable, the intersection of any two club sets is also a club set. More generally, the intersection of fewer than club sets is a club set. Consequently, the collection of all subsets of that contain a club set forms a -complete non-principal filter, known as the closed unbounded filter (or club filter).

A subset is termed stationary if it has a non-empty intersection with every closed unbounded set in . Intuitively, stationary sets are "large" enough that they cannot be avoided by any club set. Using the notation of filters, a set is stationary if and only if it does not belong to the dual ideal of the club filter (the ideal of non-stationary sets). While every club set is stationary, not every stationary set is a club; for instance, a stationary set may fail to be closed. Furthermore, while the intersection of a stationary set and a club set is stationary, the intersection of two stationary sets may be empty.

The distinction between club sets and stationary sets is central to the definitions of certain large cardinals. If is the smallest inaccessible cardinal, the set of singular strong limit cardinals below forms a closed unbounded set. Because this club set contains no regular cardinals, the set of regular cardinals below the first inaccessible is not stationary. This remains true if is the -th inaccessible cardinal for some ; the regular cardinals below it will not form a stationary set. A cardinal is defined as a Mahlo cardinal precisely when the set of regular cardinals below it is stationary. By relaxing the condition on the limit cardinals, one defines a cardinal as weakly Mahlo if it is weakly inaccessible and the set of regular cardinals below it is stationary.

The closed unbounded filter is not an ultrafilter under the standard Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the Axiom of Choice (ZFC). This is because one can find two disjoint stationary sets, which precludes the filter from deciding membership for every subset. For any regular cardinal , the set of ordinals with cofinality and the set of ordinals with cofinality are disjoint stationary subsets of . In the specific case of , the non-existence of an ultrafilter relies on the Axiom of Choice. Under ZFC, the set of limit ordinals in can be partitioned into disjoint stationary sets (a result related to Fodor's lemma). However, in models of set theory without the Axiom of Choice, such as those satisfying the Axiom of determinacy, the club filter on can be an ultrafilter, a property connected to being a measurable cardinal in those contexts.

These definitions generalize to proper classes of ordinals. A class of ordinals is unbounded if it contains arbitrarily large ordinals, and closed if the limit of any sequence of ordinals in is also in . This topological definition is equivalent to assuming the indexing class-function of is continuous. Notable examples of closed unbounded classes include the class of all infinite cardinals, the class of limit cardinals, and the class of fixed points of the -function. In contrast, the class of regular cardinals is unbounded but not closed. A class is stationary if it intersects every closed unbounded class.

Remove ads

Some "large" countable ordinals

As mentioned above (see Cantor normal form), the ordinal ε0 is the smallest satisfying the equation , so it is the limit of the sequence 0, 1, , , , etc. Many ordinals can be defined in such a manner as fixed points of certain ordinal functions (the -th ordinal such that is called , then one could go on trying to find the -th ordinal such that , "and so on", but all the subtlety lies in the "and so on"). One could try to do this systematically, but no matter what system is used to define and construct ordinals, there is always an ordinal that lies just above all the ordinals constructed by the system. Perhaps the most important ordinal that limits a system of construction in this manner is the Church–Kleene ordinal, (despite the in the name, this ordinal is countable), which is the smallest ordinal that cannot in any way be represented by a computable function (this can be made rigorous, of course). Considerably large ordinals can be defined below , however, which measure the "proof-theoretic strength" of certain formal systems (for example, measures the strength of Peano arithmetic). Large countable ordinals such as countable admissible ordinals can also be defined above the Church-Kleene ordinal, which are of interest in various parts of logic.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Topology and ordinals

Any ordinal number can be made into a topological space by endowing it with the order topology. This topology is discrete if and only if it is less than or equal to ω. In contrast, a subset of ω + 1 is open in the order topology if and only if either it is cofinite or it does not contain ω as an element.

See the Topology and ordinals section of the "Order topology" article.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The transfinite ordinal numbers, which first appeared in 1883,[16] originated in Cantor's work with derived sets. If P is a set of real numbers, the derived set P′ is the set of limit points of P. In 1872, Cantor generated the sets P(n) by applying the derived set operation n times to P. In 1880, he pointed out that these sets form the sequence P' ⊇ ··· ⊇ P(n) ⊇ P(n + 1) ⊇ ···, and he continued the derivation process by defining P(∞) as the intersection of these sets. Then he iterated the derived set operation and intersections to extend his sequence of sets into the infinite: P(∞) ⊇ P(∞ + 1) ⊇ P(∞ + 2) ⊇ ··· ⊇ P(2∞) ⊇ ··· ⊇ P(∞2) ⊇ ···.[17] The superscripts containing ∞ are just indices defined by the derivation process.[18]

Cantor used these sets in the theorems:

- If P(α) = ∅ for some index α, then P′ is countable;

- Conversely, if P′ is countable, then there is an index α such that P(α) = ∅.

These theorems are proved by partitioning P′ into pairwise disjoint sets: P′ = (P′\ P(2)) ∪ (P(2) \ P(3)) ∪ ··· ∪ (P(∞) \ P(∞ + 1)) ∪ ··· ∪ P(α). For β < α: since P(β + 1) contains the limit points of P(β), the sets P(β) \ P(β + 1) have no limit points. Hence, they are discrete sets, so they are countable. Proof of first theorem: If P(α) = ∅ for some index α, then P′ is the countable union of countable sets. Therefore, P′ is countable.[19]

The second theorem requires proving the existence of an α such that P(α) = ∅. To prove this, Cantor considered the set of all α having countably many predecessors. To define this set, he defined the transfinite ordinal numbers and transformed the infinite indices into ordinals by replacing ∞ with ω, the first transfinite ordinal number. Cantor called the set of finite ordinals the first number class. The second number class is the set of ordinals whose predecessors form a countably infinite set. The set of all α having countably many predecessors—that is, the set of countable ordinals—is the union of these two number classes. Cantor proved that the cardinality of the second number class is the first uncountable cardinality.[20]

Cantor's second theorem becomes: If P′ is countable, then there is a countable ordinal α such that P(α) = ∅. Its proof uses proof by contradiction. Let P′ be countable, and assume there is no such α. This assumption produces two cases.

- Case 1: P(β) \ P(β + 1) is non-empty for all countable β. Since there are uncountably many of these pairwise disjoint sets, their union is uncountable. This union is a subset of P′, so P' is uncountable.

- Case 2: P(β) \ P(β + 1) is empty for some countable β. Since P(β + 1) ⊆ P(β), this implies P(β + 1) = P(β). Thus, P(β) is a perfect set, so it is uncountable.[21] Since P(β) ⊆ P′, the set P′ is uncountable.

In both cases, P′ is uncountable, which contradicts P′ being countable. Therefore, there is a countable ordinal α such that P(α) = ∅. Cantor's work with derived sets and ordinal numbers led to the Cantor-Bendixson theorem.[22]

Using successors, limits, and cardinality, Cantor generated an unbounded sequence of ordinal numbers and number classes.[23] The (α + 1)-th number class is the set of ordinals whose predecessors form a set of the same cardinality as the α-th number class. The cardinality of the (α + 1)-th number class is the cardinality immediately following that of the α-th number class.[24] For a limit ordinal α, the α-th number class is the union of the β-th number classes for β < α.[25] Its cardinality is the limit of the cardinalities of these number classes.

If n is finite, the n-th number class has cardinality . If α ≥ ω, the α-th number class has cardinality .[26] Therefore, the cardinalities of the number classes correspond one-to-one with the aleph numbers. Also, the α-th number class consists of ordinals different from those in the preceding number classes if and only if α is a non-limit ordinal. Therefore, the non-limit number classes partition the ordinals into pairwise disjoint sets.

Remove ads

See also

- Counting

- Even and odd ordinals

- First uncountable ordinal

- Ordinal space

- Surreal number, a generalization of ordinals which includes negative, real, and infinitesimal values.

Notes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads