Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

First Amendment to the United States Constitution

1791 amendment limiting government restriction of civil liberties From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution prevents Congress from making laws respecting an establishment of religion; prohibiting the free exercise of religion; or abridging the freedom of speech, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly, or the right to petition the government for redress of grievances. It was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights. In the original draft of the Bill of Rights, what is now the First Amendment occupied third place. The first two articles were not ratified by the states, so the article on disestablishment and free speech ended up being first.[1][2]

The Bill of Rights was proposed to assuage Anti-Federalist opposition to Constitutional ratification. Initially, the First Amendment applied only to laws enacted by the Congress, and many of its provisions were interpreted more narrowly than they are today. Beginning with Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Supreme Court applied the First Amendment to states—a process known as incorporation—through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The First Amendment applies only to state actors.[a][3]

With regards to religious freedom, the Court has frequently cited Thomas Jefferson's call for "a wall of separation between church and State", a metaphor for the separation of religions from government and vice versa as well as the free exercise of religious beliefs that many Founders favored. Speech rights were expanded significantly in a series of 20th- and 21st-century court decisions which protected various forms of political speech, anonymous speech, campaign finance, pornography, and school speech; these rulings also defined a series of exceptions to First Amendment protections.

The Free Press Clause protects publication of information and opinions, and applies to a wide variety of media. In Near v. Minnesota (1931) and New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment protected against prior restraint—pre-publication censorship—in almost all cases. The Petition Clause protects the right to petition all branches and agencies of government for action. In addition to the right of assembly guaranteed by this clause, the Court has also ruled that the amendment implicitly protects freedom of association.

Remove ads

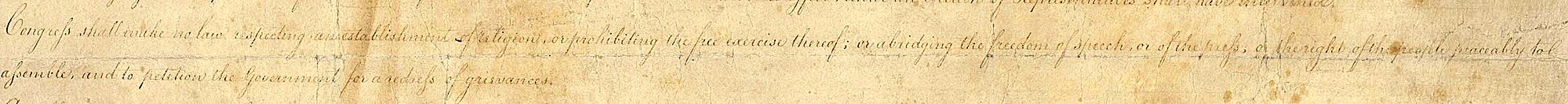

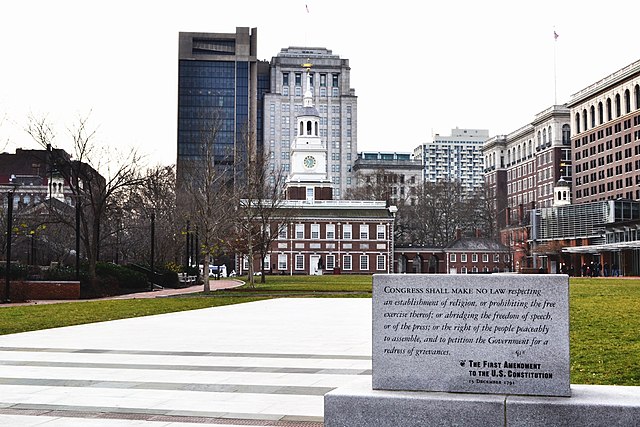

Text

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.[4]

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

The right to petition for redress of grievances was a principle included in the 1215 Magna Carta, as well as the 1689 English Bill of Rights. In 1776, the second year of the American Revolutionary War, the Virginia colonial legislature passed a Declaration of Rights that included the sentence "The freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty, and can never be restrained but by despotic Governments." Eight of the other twelve states made similar pledges. However, these declarations were generally considered "mere admonitions to state legislatures", rather than enforceable provisions.[5]

After several years of comparatively weak government under the Articles of Confederation, a Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia proposed a new constitution on September 17, 1787, featuring among other changes a stronger chief executive. George Mason, a Constitutional Convention delegate and the drafter of Virginia's Declaration of Rights, proposed that the Constitution include a bill of rights listing and guaranteeing civil liberties. Other delegates—including future Bill of Rights drafter James Madison—disagreed, arguing that existing state guarantees of civil liberties were sufficient and any attempt to enumerate individual rights risked the implication that other, unnamed rights were unprotected. After a brief debate, Mason's proposal was defeated by a unanimous vote of the state delegations.[6]

For the constitution to be ratified, however, nine of the thirteen states were required to approve it in state conventions. Opposition to ratification ("Anti-Federalism") was partly based on the Constitution's lack of adequate guarantees for civil liberties. Supporters of the Constitution in states where popular sentiment was against ratification (including Virginia, Massachusetts, and New York) successfully proposed that their state conventions both ratify the Constitution and call for the addition of a bill of rights. The U.S. Constitution was eventually ratified by all thirteen states. In the 1st United States Congress, following the state legislatures' request, James Madison proposed twenty constitutional amendments, and his proposed draft of the First Amendment read as follows:

The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed. The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable. The people shall not be restrained from peaceably assembling and consulting for their common good; nor from applying to the Legislature by petitions, or remonstrances, for redress of their grievances.[7]

This language was greatly condensed by Congress, and passed the House and Senate with almost no recorded debate, complicating future discussion of the Amendment's intent.[8][9] Congress approved and submitted to the states for their ratification twelve articles of amendment on September 25, 1789. The revised text of the third article became the First Amendment, because the last ten articles of the submitted 12 articles were ratified by the requisite number of states on December 15, 1791, and are now known collectively as the Bill of Rights.[10][11]

Remove ads

Freedom of religion

Summarize

Perspective

Religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion, is "the right of all persons to believe, speak, and act – individually and in community with others, in private and in public – in accord with their understanding of ultimate truth."[13] The acknowledgement of religious freedom as the first right protected in the Bill of Rights points toward the American founders' understanding of the importance of religion to human, social, and political flourishing.[13] Freedom of religion[13] is protected by the First Amendment through its Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause, which together form the religious liberty clauses of the First Amendment.[14]

The first clause prohibits any governmental "establishment of religion" and the second prohibits any governmental interference with "the free exercise thereof."[15] These clauses of the First Amendment encompass "the two big arenas of religion in constitutional law. Establishment cases deal with the Constitution's ban on Congress endorsing, promoting or becoming too involved with religion. Free exercise cases deal with Americans' rights to practice their faith."[16] Both clauses sometimes compete with each other. The Supreme Court in McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union (2005) clarified this by the following example: When the government spends money on the clergy, then it looks like establishing religion, but if the government cannot pay for military chaplains, then many soldiers and sailors would be kept from the opportunity to exercise their chosen religions.[15] The Supreme Court developed the preferred position doctrine.[17] In Murdock v. Pennsylvania (1943) the Supreme Court stated: "Freedom of press, freedom of speech, freedom of religion are in a preferred position,"[18] adding that "[plainly], a community may not suppress, or the state tax, the dissemination of views because they are unpopular, annoying or distasteful."[18]

The First Amendment tolerates neither governmentally established religion nor governmental interference with religion.[19] One of the central purposes of the First Amendment, the Supreme Court wrote in Gillette v. United States (1970), consists "of ensuring governmental neutrality in matters of religion."[20] In Wallace v. Jaffree regarding silent school prayer, it was maintained that the central liberty that unifies the various clauses in the First Amendment is the individual's freedom of conscience.[21] In Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition (2002), the Court stated: First Amendment freedoms are most in danger when the government seeks to control thought or to justify its laws for that impermissible end. The right to think is the beginning of freedom, and speech must be protected from the government because speech is the beginning of thought.[22]

Establishment of religion

The Establishment Clause forbids federal, state, and local laws whose purpose is "an establishment of religion."[23] The term "establishment" denoted in general direct aid to the church by the government.[24] In Larkin v. Grendel's Den, Inc. (1982), the Supreme Court stated that "the core rationale underlying the Establishment Clause is preventing "a fusion of governmental and religious functions."[25] The Establishment Clause acts as a double security, for it both bars religious control over government and political control over religion.[14] This is reflected in Reynolds v. United States (1878), in which the Supreme Court declared that Congress could not legislate over religious opinion except to curtail that which imperils "peace and good order."[26]

Originally, the First Amendment applied only to the federal government, and some states continued official state religions after ratification.[27] However, in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Supreme Court incorporated the Establishment Clause (i.e., made it apply against the states).[28] The First Amendment's framers knew that intertwining government with religion could lead to bloodshed or oppression, because this happened too often historically. To prevent this dangerous development, they set up the Establishment Clause as a line of demarcation between the functions and operations of the institutions of religion and government in society.[29] At the core of the Establishment Clause lays the principle of denominational neutrality.[30] The clearest command of the Establishment Clause is, according to the Supreme Court in Larson v. Valente (1982) that one religious denomination cannot be officially preferred over another.[31]

While its meaning is not clarified in the Constitution, the Establishment Clause is often understood as mandating the separation of church and state.[32] The founder of Rhode Island Roger Williams coined the metaphor, and Thomas Jefferson famously used it in an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptists:[32] "[I believe] with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, [and] that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, … thus building a wall of separation between Church & State."[33] This metaphor was introduced as a judicial doctrine in Everson,[34]: 146 and to this day, it defines discussion on the Establishment Clause.[35]

The First Amendment's prohibition on an establishment of religion includes many things from prayer in widely varying government settings over financial aid for religious individuals and institutions to comment on religious questions.[15] However, its precise meaning is heavily debated. The National Constitution Center observes that, absent some common interpretations by jurists, the precise meaning of the Establishment Clause is unclear and that decisions by the Supreme Court relating to the Establishment Clause often are by 5–4 votes.[36] One such controversial decision was taken in Engel v. Vitale (1962), which held it unconstitutional for public schools to organize prayer or Bible reading sessions for students, even if on a voluntary basis.[36]

The predominant means by which the Court has enforced the Establishment Clause is the Lemon test, founded in the case Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971).[37] It determined whether an action is an establishment if: a) the statute (or practice) lacked a secular purpose; b) its principal or primary effect advanced or inhibited religion; or c) it fostered excessive government entanglement with religion.[38] After the Supreme Court ruling in the coach praying case of Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022), the Lemon Test may have been replaced or complemented with a reference to historical practices and understandings.[39][40]

The opponents of those who firmly subscribe to the separation of church and state: separationists, are accommodationists.[41] They argue, along with Justice William O. Douglas, that "[w]e are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being."[38] Chief Justice Warren E. Burger coined the term "benevolent neutrality" as a combination of neutrality and accommodationism to characterize a way to ensure that the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause do not contradict each other.[42][b] Burger's successor, William Rehnquist, called for the abandonment of the "wall of separation between church and State" metaphor in Wallace v. Jaffree (1985), because he believed this metaphor was based on bad history and proved itself useless as a guide to judging.[43] For many conservatives, the Establishment Clause solely prevents the government from promoting a religious sect or setting up a national church but not from "developing policies that encourage general religious beliefs."[44] In Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), the Supreme Court observed that the "Constitution does not require complete separation of church and state; it affirmatively mandates accommodation, not merely tolerance, of all religions, and forbids hostility toward any."[45]

Free exercise of religion

The acknowledgement of religious freedom as the first right protected in the Bill of Rights points toward the American founders' understanding of the importance of religion to human, social, and political flourishing. The First Amendment makes clear that it sought to protect "the free exercise" of religion, or what might be called "free exercise equality."[13] Free exercise is the liberty of persons to reach, hold, practice and change beliefs freely according to the dictates of conscience. The Free Exercise Clause prohibits governmental interference with religious belief and, within limits, religious practice.[14] "Freedom of religion means freedom to hold an opinion or belief, but not to take action in violation of social duties or subversive to good order."[46] The clause withdraws from legislative power, state and federal, the exertion of any restraint on the free exercise of religion. Its purpose is to secure religious liberty in the individual by prohibiting any invasions thereof by civil authority.[47] In Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), the Court held that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applied the Free Exercise Clause to the states.[48]

The Court further explained in Employment Division v. Smith (1990) that "the 'exercise of religion' often involves not only belief and profession but the performance of (or abstention from) physical acts: assembling with others for a worship service, participating in sacramental use of bread and wine, proselytizing, abstaining from certain foods or certain modes of transportation."[49] Judge Learned Hand said in the 1953 case Otten v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co.: "The First Amendment … gives no one the right to insist that, in pursuit of their own interests others must conform their conduct to his own religious necessities."[50]

The Free Exercise Clause offers a double protection, for it is a shield not only against outright prohibitions with respect to the free exercise of religion but also against penalties on the free exercise of religion and against indirect governmental coercion.[51] The Supreme Court stated in Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017) that religious observers are protected against unequal treatment by virtue of the Free Exercise Clause and laws which target the religious for "special disabilities" based on their "religious status" must be covered by the application of strict scrutiny.[52]

The Court first fully addressed the Free Exercise Clause's meaning in Reynolds v. United States (1879), which concerned the legality of polygamy in the U.S. the Supreme Court found that while laws cannot interfere with religious belief and opinions, laws can regulate religious practices like polygamy andhuman sacrifice.[53] While the right to have religious beliefs is absolute, the freedom to act on such beliefs is not absolute.[54] Such an interpretation was largely abandoned in Sherbert v. Verner (1963). Here, the Court required states required states to meet the "strict scrutiny" standard when refusing to accommodate religiously motivated conduct.[55] In Employment Divison, however, the Court reaffirmed Reynolds as it held that two counsellors could be dismissed for using a drug common in Native American religious worship without violating the Free Exercise Clause.[55]

Employment Division v. Smith set the precedent[56] "that laws affecting certain religious practices do not violate the right to free exercise of religion as long as the laws are neutral, generally applicable, and not motivated by animus to religion."[57]

To accept any creed or the practice of any form of worship cannot be compelled by laws, because, as stated by the Supreme Court in Braunfeld v. Brown (1961), the freedom to hold religious beliefs and opinions is absolute.[58]

In some cases, the Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause collide with each other, as enforced separation of church and state ends up discriminating against religious groups. For example, Lamb's Chapel v. Center Moriches Union Free School District (1993), the Court ruled that Center Moriches school board could not bar a Christian group from using school facilities after hours, even though the board claimed that such use would constitute the establishment of a religion.[59]

Remove ads

Freedom of speech

Summarize

Perspective

The First Amendment broadly protects the rights of free speech and free press.[60] Free speech means the free and public expression of opinions without censorship, interference, or restraint by the government.[61][62][63][64] The term "freedom of speech" embedded in the First Amendment encompasses the decision what to say as well as what not to say.[65] The speech covered by the First Amendment covers many ways of expression and therefore protects what people say as well as how they express themselves.[66] Free press means the right of individuals to express themselves through publication and dissemination of information, ideas, and opinions without interference, constraint, or prosecution by the government.[67][68] In Murdock v. Pennsylvania (1943), the Supreme Court stated that "Freedom of press, freedom of speech, freedom of religion are in a preferred position."[69] The Court added that a community may not suppress, or the state tax, the dissemination of views because they are unpopular, annoying, or distasteful.[70] The Constitution protects, according to the Supreme Court in Stanley v. Georgia (1969), the right to receive information and ideas, regardless of their social worth, and to be generally free from governmental intrusions into one's privacy and control of one's thoughts.[71] As stated by the Court in Stanley: "If the First Amendment means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch. Our whole constitutional heritage rebels at the thought of giving government the power to control men's minds."[72]

Despite the common misconception that the First Amendment prohibits anyone from limiting free speech,[73] the text of the amendment prohibits only the federal government, the states, and local governments from doing so.[74][75] State constitutions provide free speech protections similar to those of the U.S. Constitution. In a few states, such as California, a state constitution has been interpreted as providing more comprehensive protections than the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has permitted states to extend such enhanced protections, most notably in Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins.[76]

The Supreme Court of the United States characterized the rights of free speech and free press as fundamental personal rights and liberties and noted that the exercise of these rights lies at the foundation of free government by free men.[77][78] The Supreme Court stated in Thornhill v. Alabama (1940) that the freedom of speech and of the press guaranteed by the United States Constitution embraces at the least the liberty to discuss publicly and truthfully all matters of public concern, without previous restraint or fear of subsequent punishment.[79] The Court noted in Bridges v. California (1941): "The ability to publicly criticize even the most prominent politicians and leaders without fear of retaliation is part of the First Amendment, because political speech is core First Amendment speech. … For it is a prized American privilege to speak one's mind, although not always with perfect good taste, on all public institutions."[80] In Bond v. Floyd (1966), a case involving the Constitutional shield around the speech of elected officials, the Supreme Court declared that the First Amendment central commitment is that, in the words of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), "debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open".[81] The Court further explained that just as erroneous statements must be protected to give freedom of expression the breathing space it needs to survive, so statements criticizing public policy and the implementation of it must be similarly protected:

But, above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content. ... To permit the continued building of our politics and culture, and to assure self-fulfillment for each individual, our people are guaranteed the right to express any thought, free from government censorship. The essence of this forbidden censorship is content control. Any restriction on expressive activity because of its content would completely undercut the "profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open."[60]

The level of protections with respect to free speech given by the First Amendment is not limitless.[82] As stated in his concurrence in Mosley, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger said: "the First Amendment does not literally mean that we 'are guaranteed the right to express any thought, free from government censorship.'"[83]

Attached to the core rights of free speech and free press are several peripheral rights that make these core rights more secure. The peripheral rights encompass not only freedom of association, including privacy in one's associations, but also, in the words of Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), "the freedom of the entire university community", i.e., the right to distribute, the right to receive, and the right to read, as well as freedom of inquiry, freedom of thought, and freedom to teach.[84]

Wording of the clause

The First Amendment bars Congress from "abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press." U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens commented about this phraseology in a 1993 journal article: "I emphasize the word 'the' in the term 'the freedom of speech' because the definite article suggests that the draftsmen intended to immunize a previously identified category or subset of speech." Stevens said that, otherwise, the clause might absurdly immunize things like false testimony under oath.[85] Like Stevens, journalist Anthony Lewis wrote: "The word 'the' can be read to mean what was understood at the time to be included in the concept of free speech."[86] But what was understood at the time is not entirely clear.[87] In the late 1790s, the lead author of the speech and press clauses, James Madison, argued against narrowing this freedom to what had existed under English common law: "The practice in America must be entitled to much more respect. In every state, probably, in the Union, the press has exerted a freedom in canvassing the merits and measures of public men, of every description, which has not been confined to the strict limits of the common law."[88]

Madison wrote this in 1799, when he was in a dispute about the constitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Laws, which was legislation enacted in 1798 by President John Adams's Federalist Party to ban seditious libel. Madison believed that legislation to be unconstitutional, and his adversaries in that dispute, such as John Marshall, advocated the narrow freedom of speech that had existed in the English common law.[89]

Historical outlook

The Supreme Court declined to rule on the constitutionality of any federal law regarding the Free Speech Clause until the twentieth century[90] and tended to overlook free speech protection.[82] For example, the Court never ruled on the Alien and Sedition Acts; three Supreme Court justices riding circuit presided over sedition trials without indicating any reservations.[90] The leading critics of the law, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, argued for the Acts' unconstitutionality based on the First Amendment and other Constitutional provisions.[91] Punishment for blasphemy was affirmed throughout the nineteenth century.[82]

During the patriotic fervor of World War I and the Red Scare,[93] the Court sought to restrict speech seen as promoting crime.[82] In one such case, Socialist Party of America official Charles Schenck was convicted under the Espionage Act of 1917 for publishing leaflets urging resistance to the draft.[94] Schenck appealed, arguing that the Espionage Act violated the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. In Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court unanimously rejected Schenck's appeal and affirmed his conviction.[95] Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. explained that "the question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent."[96]

However, this trend changed in the 1920s, as the Court began interpreting the First Amendment more broadly.[82] In Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Court upheld the conviction of Benjamin Gitlow, who had been convicted after distributing a manifesto calling for a "revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat."[98] At the same time, a majority found that the First Amendment applied to state laws as well as federal laws,[99][100] the first time the Court formally accepted this view.[82] Free speech cases thereafter would generally concern state suppression.[100] In Whitney v. California (1927), Justice Louis Brandeis wrote a dissent in which he argued for broader protections for political speech: "Those who won our independence ... believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; … that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government."[101]

In Herndon v. Lowry (1937), the Court heard the case of African American Communist Party organizer Angelo Herndon, who had been convicted under the Slave Insurrection Statute for advocating black rule in the southern United States. The Court reversed Herndon's conviction, holding that Georgia had failed to demonstrate any "clear and present danger" in Herndon's political advocacy.[102] The importance of freedom of speech in the context of "clear and present danger" was emphasized in Terminiello v. City of Chicago (1949), where Justice William O. Douglas wrote for the Court that "a function of free speech under our system is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger."[103]

Following Thornhill v. Alabama (1940), the Court refrained from applying clear and present danger test in several free speech cases involving incitement to violence.[104] In 1940, Congress enacted the Smith Act, making it illegal to advocate "the propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force and violence."[105] In Dennis v. United States (1951), the Court upheld the law.[106][c] In a concurring opinion, Justice Felix Frankfurter proposed a "balancing test," which soon supplanted the "clear and present danger" test: "The demands of free speech in a democratic society as well as the interest in national security are better served by candid and informed weighing of the competing interests, within the confines of the judicial process."[106]

During the Vietnam War, the Court's position on public criticism of the government changed drastically,[107] as its reading of the First Amendment broadened further.[82] In 1969, it handed down its decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), expressly overruling Whitney v. California.[107] Brandenburg discarded the "clear and present danger" test introduced in Schenck and further eroded Dennis.[108][109] Now the Supreme Court referred to the right to speak openly of violent action and revolution in broad terms: "the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not allow a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or cause such action."[110][107]

Political speech

Anonymous speech

The Supreme Court has generally safeguarded anonymous speech under the First Amendment. This is especially pertinent in cases concerning controversial political groups, such as the NAACP and the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, where their anonymity helped secure their right to assembly.[111] In Talley v. California (1960), the Court struck down a Los Angeles city ordinance that criminalized distributing anonymous pamphlets. Justice Hugo Black wrote in the majority opinion: "There can be no doubt that such an identification requirement would tend to restrict freedom to distribute information and thereby freedom of expression."[112] However, the court has been less protective of such speech in campaign finance donations and on the internet.[111]

Campaign finance

The Court considers campaign donations as speech sometimes protected by the First Amendment.[113] In Buckley v. Valeo (1976), the Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of limits on campaign contributions,[114] saying they "serve[d] the basic governmental interest in safeguarding the integrity of the electoral process without directly impinging upon the rights of individual citizens and candidates to engage in political debate and discussion."[115] However, the same decision established campaign finance as a form of political speech.[116] Over thirty years later, the Court ruled in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) that restrictions on indepedent political spending by corporations or unions violated the Free Speech Clause and were therefore unconstitutional.[117] This, in effect, "enabled corporations and other outside groups to spend unlimited money on elections."[116] Federal aggregate limits on how much a person can donate to candidates, parties, and political action committees were later found to clash with the First Amendment in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission (2014).[118]

Professional/occupational speech

Some federal courts have suggested that a First Amendment distinction exists between speech directed at the public and speech aimed at individuals in a professional, fiduciary, or business context—so called occupational, or professional, speech.[119] For example, in Lowe v. Securities Exchange Commission (1985), Justice Byron White argued that the government could permissibly restrict the speech of "[o]ne who takes the affairs of a client personally in hand and purports to exercise judgment on behalf of the client in the light of the client's individual needs and circumstances."[119] Over time, a number of courts adopted Justice White's view in what became known as the "professional speech doctrine."[120] In National Institute of Family & Life Advocates v. Becerra (2018), however, the Supreme Court repudiated the doctrine, claiming that "this Court has never recognized 'professional speech' as a separate category of speech subject to different rules."[121]

Flag desecration

There has been significant debate over whether flag desecration is protected by the First Amendment.[122] The Supreme Court addressed this issue in Street v. New York (1969), amid a popular trend of burning the U.S. flag to protest the Vietnam War.[123] While it found a New York law criminalizing attacking any U.S. flag in various ways[124] unconstitutional, it left the constitutionality of flag-burning unaddressed.[125][123] However, in Texas v. Johnson (1989), the Court explicitly ruled that flag burnings are a form of protected speech.[126]

School speech

In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), the Supreme Court extended free speech rights to students in school. The case involved several students who were punished for wearing black armbands to protest the Vietnam War.[127] The Court ruled that the school could not restrict symbolic speech that did not "materially and substantially" interrupt school activities.[128] Justice Abe Fortas wrote: "It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate."[129] However, since 1969, the Court has also placed several limitations on Tinker. In Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the Court found that schools need not tolerate student speech that is inconsistent with their basic educational mission,[130] and in Morse v. Frederick (2007), it ruled that schools could restrict student speech at school-sponsored events, even events away from school grounds, if students promote "illegal drug use."[131] In 2014, the University of Chicago released the "Chicago Statement", a free speech policy statement designed to combat censorship on campus, which was later adopted by other prestigious universities.[132][133]

Compelled speech

The Supreme Court has determined that the First Amendment also protects citizens from being compelled by the government to say or to pay for certain speech. In West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), it was ruled that school children could not be punished for refusing either to say the pledge of allegiance or salute the American flag.[134] The Court determined in Janus v. AFSCME (2018) that requiring a public sector employee to pay dues to a union of which he is not a member violated the First Amendment.[135]

Hate and offensive speech

Hate speech, while difficult to define precisely, is safeguarded by the First Amendment.[136][137] In fact, Justice John Marshall Harlan II addressed the subjectivity that belies one's understanding a statement as hate speech: "One man's vulgarity is another man's lyric."[138][136] The American Library Association provides a general definition of hate speech: "any form of expression through which speakers intend to vilify, humiliate, or incite hatred against a group or a class of persons on the basis of race, religion, skin color, sexual identity, gender identity, ethnicity, disability, or national origin."[137] "Freedom for the thought we hate," as expressed by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., is guaranteed, and the Court has recognized it.[136] In one case, Snyder v. Phelps (2011), the Court found that individuals who picketed a military funeral holding signs stating "God Hates Fags" and "Thank God for Dead Soldiers" were acting within the limits of the First Amendment.[139]

However, a distinction is made between hate speech and hate crimes. The latter stirs up criminal activity or threatens specific individuals or groups and is therefore illegal.[137] Fighting words—personal insults and deliberately violent statements directed at a particular person or group—also do not qualify as free speech. For instance, in the 1940s, a man who called a police officer a "God-damned racketeer” and "a damned fascist" was arrested, and the Court upheld his conviction.[140] On the other hand, in Texas v. Johnson (1989), it did not find public flag desecration unconstitutional and, in fact, deemed it a form of protected speech: while the act was offensive, it was not meant as a direct personal insult toward any passersby.[141] Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote in the decision that "if there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea offensive or disagreeable."[142] The fighting words doctrine itself has been criticized and labelled as a "relic" of a bygone age.[141]

Commercial speech

Commercial speech, done for the purpose of selling a product or service,[143] is entitled to First Amendment protections but not as much as other forms of speech, such as that political.[144] The Supreme Court began treating commerical speech thus in the 1970s; in Virginia State Pharmacy Board v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc. (1976), it struck down a state law barring the advertisement of drug prices by pharmacies.[144] The Court has since noted that "speech does not lose its protection simply because money is transacted through it," but this does not make commerical speech immune to regulation.[144] In Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission (1980), the Court developed a four-pronged test to clarify when to restrict such speech: it must be misleading or involve illegal activity; the government must prove "substantial interest" in regulating it; the regulation must directly advance the governmental interest asserted; and the regulation must not be more strict than necessary.[143] For example, the 1986 case Posadas de Puerto Rico Associates v. Tourism Company of Puerto Rico saw the Court uphold Puerto Rico law that barred casinos from advertising to its residents, finding that it preserved the federal government's interest of preventing gambling and to protect residents' safety and well-being.[144]

Defamation

For the first two-hundred years of American jurisprudence, libel placed specific emphasis on the result of the allegedly harmful publication[146] over whether the publication was true or false.[147] Libelous publications tended to "degrade and injure another person" or "bring him into contempt, hatred or ridicule."[146] Two centuries later, the Supreme Court's ruling in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) transformed American defamation law.[148] Common law malice consisted of "ill-will" or "wickedness," and thereafter, public officials seeking a lawsuit against a tortfeasor needed to prove by "clear and convincing evidence" that there was actual malice.[149][150] "Libel can claim no talismanic immunity from constitutional limitations," Justice William J. Brennan Jr. noted.[145] While the actual malice standard applies to public officials and public figures, in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974) the Court ruled that actual malice need not be shown in cases involving private individuals.[145] Moreover, in Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co. (1990), it was ruled that the First Amendment offers no wholesale exception to defamation law for statements labeled "opinion," but instead that a statement must be provably false before it can be the subject of a libel suit.[151]

Obscenity and pornography

According to the Supreme Court, the First Amendment's protection of free speech does not necessarily apply to obscene speech.[152] It first tackled the matter in Roth v. United States (1957), in which it ruled that the First Amendment did not protect obscenity; the same case founded a standard to determine whether the material in question qualifies as obscenity.[152] Throughout the following decade, members of the Court often reviewed films individually in a court building screening room to determine if they should be considered obscene.[153] Justice Potter Stewart, in Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964), famously said that, although he could not precisely define pornography, "I know it when I see it."[154] The so-called Roth test was expanded when the Court decided Miller v. California (1973). Under the Miller test, a work is obscene if: "a) 'the average person, applying contemporary community standards' would find the work, as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest … b) the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law, and (c) the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.[155]

Pornography, except for child pornography, is in practice free of governmental restrictions in the U.S., though pornography about "extreme" sexual practices is occasionally prosecuted.[27] Child pornography is not subject to the Miller test, as the Supreme Court decided in New York v. Ferber (1982) and Osborne v. Ohio (1990),[156][157] ruling that the government's interest in protecting children from abuse was paramount.[158][159] Personal possession of obscene material in the home may not be prohibited by law, as per Stanley v. Georgia (1969).[152]

Remove ads

Freedom of the press

Summarize

Perspective

The Free Press Clause protects the right of individuals to express themselves through publication and dissemination of information, ideas and opinions without interference, constraint or prosecution by the government.[67][68] In Lovell v. City of Griffin (1938),[160] Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes defined "press" as "every sort of publication which affords a vehicle of information and opinion".[161] This right has been extended to media including newspapers, books, plays, movies, and video games.[162] While it is an open question whether people who blog or use social media are journalists entitled to protection by media shield laws,[163] they are protected equally by the Free Speech Clause and the Free Press Clause, because both clauses do not distinguish between media businesses and nonprofessional speakers.[67][68][164] Justice Felix Frankfurter stated in a concurring opinion in another case succinctly: "[T]he purpose of the Constitution was not to erect the press into a privileged institution but to protect all persons in their right to print what they will as well as to utter it."[165] In Mills v. Alabama (1943) the Supreme Court laid out the purpose of the free press clause: "… there is practically universal agreement that a major purpose of [the First Amendment] was to protect the free discussion of governmental affairs. … the press serves and was designed to serve as a powerful antidote to any abuses of power by governmental officials, and as a constitutionally chosen means for keeping officials elected by the people responsible to all the people whom they were selected to serve."[166] Justice Lewis F. Powell clarifies in Branzburg v. Hayes (1972) that a claim for press privilege "should be judged on its facts by the striking of a proper balance between freedom of the press and the obligation of all citizens to give relevant testimony with respect to criminal conduct."[167]

A landmark decision for press freedom came in Near v. Minnesota (1931),[168] in which the Supreme Court rejected prior restraint (pre-publication censorship). In this case, the Minnesota legislature passed a statute allowing courts to shut down "malicious, scandalous and defamatory newspapers", allowing a defense of truth only in cases where the truth had been told "with good motives and for justifiable ends".[169] The Court applied the Free Press Clause to the states, rejecting the statute as unconstitutional. Hughes quoted Madison in the majority decision, writing, "The impairment of the fundamental security of life and property by criminal alliances and official neglect emphasizes the primary need of a vigilant and courageous press."[170]

However, Near also noted an exception, allowing prior restraint in cases such as "publication of sailing dates of transports or the number or location of troops".[171] This exception was a key point in another landmark case four decades later: New York Times Co. v. United States (1971),[172] in which the administration of President Richard Nixon sought to ban the publication of the Pentagon Papers, classified government documents about the Vietnam War secretly copied by analyst Daniel Ellsberg. The Court found that the Nixon administration had not met the heavy burden of proof required for prior restraint. Justice Brennan, drawing on Near in a concurrent opinion, wrote that "only governmental allegation and proof that publication must inevitably, directly, and immediately cause the occurrence of an evil kindred to imperiling the safety of a transport already at sea can support even the issuance of an interim restraining order." Justices Black and Douglas went still further, writing that prior restraints were never justified.[173]

The courts have rarely treated content-based regulation of journalism with any sympathy. In Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974),[174] the Court unanimously struck down a state law requiring newspapers criticizing political candidates to publish their responses. The state claimed the law had been passed to ensure journalistic responsibility. The Supreme Court found that freedom, but not responsibility, is mandated by the First Amendment and so it ruled that the government may not force newspapers to publish that which they do not desire to publish,[175] establishing a corporation's right not to speak.[176]

Content-based regulation of television and radio, however, have been sustained by the Supreme Court in various cases. Since there is a limited number of frequencies for non-cable television and radio stations, the government licenses them to various companies. However, the Supreme Court has ruled that the problem of scarcity does not allow the raising of a First Amendment issue. The government may restrain broadcasters, but only on a content-neutral basis. In Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation,[177] the Supreme Court upheld the Federal Communications Commission's authority to restrict the use of "indecent" material in broadcasting.

State governments retain the right to tax newspapers, just as they may tax other commercial products. Generally, however, taxes that focus exclusively on newspapers have been found unconstitutional, such as n Grosjean v. American Press Co. (1936).[178] In Leathers v. Medlock (1991), the Supreme Court found that states may treat different types of the media differently, such as by taxing cable television, but not newspapers.[179] The Court found that "differential taxation of speakers, even members of the press, does not implicate the First Amendment unless the tax is directed at, or presents the danger of suppressing, particular ideas."[180]

Remove ads

Right to petition and freedom of assembly

Summarize

Perspective

The Petition Clause protects the right "to petition the government for a redress of grievances".[67] The right expanded over the years: "It is no longer confined to demands for 'a redress of grievances', in any accurate meaning of these words, but comprehends demands for an exercise by the government of its powers in furtherance of the interest and prosperity of the petitioners and of their views on politically contentious matters."[181] The right to petition the government for a redress of grievances therefore includes the right to communicate with government officials, lobbying government officials and petitioning the courts by filing lawsuits with a legal basis.[164] According to the Supreme Court, petitions on behald of private interests seeking personal gain[182] and those calling for peaceful legislative change are also protected.[183]

The Petition Clause first came to prominence in the 1830s, when Congress established the gag rule barring anti-slavery petitions from being heard; the rule was overturned by Congress several years later. Petitions against the Espionage Act of 1917 resulted in imprisonments. The Supreme Court did not rule on either issue.[181] Today, this right encompasses petitions to all three branches of the federal government—the Congress, the executive and the judiciary—and has been extended to the states through incorporation.[181][183] In Borough of Duryea v. Guarnieri (2011), the Supreme Court declared that the Free Speech Clause and the Petition Clause are mutually integral to the democratic process as both foster the exchange and expression of ideas.[184]

The right of assembly is the individual right of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ideas.[185] This right is deemed equally important as those of free speech and free press, as observed by the Court in De Jonge v. Oregon (1937).[181] The right of peaceable assembly was originally distinguished from the right to petition.[181] In United States v. Cruikshank (1875),[186] the first case in which the right to assembly was before the Supreme Court,[181] the court broadly declared the outlines of the right of assembly and its connection to the right of petition: "The very idea of a government, republican in form, implies a right on the part of its citizens to meet peaceably for consultation in respect to public affairs and to petition for a redress of grievances."[187]

Justice Morrison Waite's opinion for the Court carefully distinguished the right to peaceably assemble as a secondary right, while the right to petition was labeled to be a primary right. Later cases, however, paid less attention to these distinctions.[181] An example of this is Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization (1939), where it was decided that the freedom of assembly covered by the First Amendment applies to public forums like streets and parks.[188][181] In Hague the right of assembly was given a broad meaning, because the right of assembly can be used "for communication of views on national questions"[189] as well as for "holding meetings and disseminating information whether for the organization of labor unions or for any other lawful purpose."[190]

Remove ads

Freedom of association

Summarize

Perspective

Although the First Amendment does not explicitly mention freedom of association, the Supreme Court ruled, in NAACP v. Alabama (1958),[191][192] that this freedom was protected by the amendment and that privacy of membership was an essential part of this freedom.[193] In Roberts v. United States Jaycees (1984), the Court stated that "implicit in the right to engage in activities protected by the First Amendment" is "a corresponding right to associate with others in pursuit of a wide variety of political, social, economic, educational, religious, and cultural ends".[194] In Roberts the Court held that associations may not exclude people for reasons unrelated to the group's expression, such as gender.[195]

However, in Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston (1995),[196] the Court ruled that a group may exclude people from membership if their presence would affect the group's ability to advocate a particular point of view.[197] Likewise, in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000),[198] the Court ruled that a New Jersey law, which forced the Boy Scouts of America to admit an openly gay member, to be an unconstitutional abridgment of the Boy Scouts' right to free association.[199]

Remove ads

See also

- Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- Censorship in the United States

- First Amendment audits

- Free speech zone

- Freedom of speech

- Government speech

- List of amendments to the Constitution of the United States

- List of United States Supreme Court cases involving the First Amendment

- Marketplace of ideas

- Military expression

- Photography Is Not a Crime

- Section 116 of the Constitution of Australia

- United States Postal Service

- United States free speech exceptions

- Williamsburg Charter

Remove ads

Explanatory notes

- See for the topic First Amendment and state actor exemplarily the 2019 United States Supreme Court case Manhattan Community Access Corp. v. Halleck, No. 17-1702, 587 U.S. ___ (2019).

- Burger explained the term "benevolent neutrality" with respect to the interplay of the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause in this way in Walz: "The course of constitutionality neutrality in this area cannot be an absolutely straight line; rigidity could well defeat the basic purpose of these provisions, which is to insure that no religion be sponsored or favored, none commanded, and none inhibited. The general principle deducible from the First Amendment and all that has been said by the Court is this: that we will not tolerate either governmentally established religion or governmental interference with religion. Short of those expressly proscribed governmental acts there is room for play in the joints productive of a benevolent neutrality which will permit religious exercise to exist without sponsorship and without interference."[42]

- Justice Tom C. Clark did not participate because he had ordered the prosecutions when he was Attorney General.

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads