Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

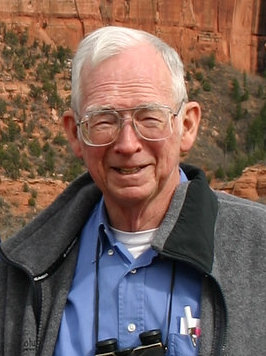

Holmes Rolston III

American philosopher (1932–2025) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Holmes Rolston III (November 19, 1932 – February 12, 2025) was an American philosopher who was University Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at Colorado State University. He is best known for his contributions to environmental ethics and the relationship between science and religion. Among other honors, Rolston won the 2003 Templeton Prize, awarded by Prince Philip in Buckingham Palace. He gave the Gifford Lectures, University of Edinburgh, 1997–1998. He also served on the Advisory Council of METI (Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence).

The Darwinian model is used to define the main thematic concepts in Rolston's philosophy and, in greater depth, the general trend of his thinking.[1]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Rolston was born on November 19, 1932, in Staunton, Virginia.[2] His grandfather, Holmes Rolston, and his father, Holmes Rolston Jr. (who did not use the Jr.), were Presbyterian ministers.[3] He was married on June 1, 1956, to Jane Irving Wilson, with whom he had a daughter and son.[2][4] He held a B.S. in physics and mathematics from Presbyterian-affiliated Davidson College (1953) and a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Union Presbyterian Seminary (1956).[5] He was ordained to the ministry of the Presbyterian Church (USA) also in 1956. He received a Ph.D. from the University of Edinburgh in 1958;[6] his advisor was Thomas F. Torrance.

Rolston was a Presbyterian minister in Rockbridge Baths, Virginia, before he was ousted by his congregation in 1965, amid conflict over his environmental interests.[2] Afterward, he turned to academia, and after earning an M.A. in the philosophy of science from the University of Pittsburgh in 1968, began his career later that year as an assistant professor of philosophy at Colorado State University and becoming a full professor in 1976. He became a University Distinguished Professor in 1992. He gave the Gifford Lectures, University of Edinburgh, 1998–1999. He was named Templeton Prize laureate in 2003. He has lectured by invitation on all seven continents.[7]

In 1990, Rolston became the first president of the International Society for Environmental Ethics.[8]

Rolston died at his home in Fort Collins, Colorado, on February 12, 2025, aged 92.[2][9]

Remove ads

Views on rights

Summarize

Perspective

Rolston accepted that humans have rights but criticized the idea of animal rights and extending rights to flora because there are no rights in the wild. Rolston argued that a rights approach to sentient life is ill-suited to ecosystems and when a moral agent is faced with suffering in an ecosystem there is no duty to intervene.[10] In 1991, Rolston stated:

When we try to use culturally extended rights and psychologically based utilities to protect the flora or even the insentient fauna, to protect endangered species or ecosystems, we can only stammer. Indeed, we get lost trying to protect bighorns, because, in the wild, cougars are not respecting the rights or utilities of the sheep they slay, and, in culture, humans slay sheep and eat them regularly, while humans have every right not to be eaten by either humans or cougars. There are no rights in the wild, and nature is indifferent to the welfare of particular animals.[11]

Rolston also argued that "environmental ethics accepts predation as good in wild nature", Rolston said that wild predation should be respected because it has great importance for larger ecosystem and evolutionary processes.[12] For example, predators eliminate weak and unfit individuals from populations of prey organisms contributing to the overall integrity of those species and culling of unfit organisms by predators is vital to the evolutionary process of natural selection, which Rolston believes trends towards more complex and diverse life forms.[12] Rolston has stated that predation is an integral part of nature which "yields a flourishing of species" and has contributed to some of the most significant achievements in natural history and that without predation, life on earth would be greatly impoverished.[12]

Rolston argued that when humans encounter wild nature they are not under any duty or obligation to alleviate any wild animal suffering and that since animals in the wild have no claim to a pleasant life free of pain then humans have no moral duty to provide them with one.[12] Rolston said that this also holds true for domesticated animals because although they have been brought under the care of humans, their origins are from wild nature so the comparison class for assessing conduct towards them should not be from humans but from other animals. In Rolston's view domesticated animals like wild animals "have no right or welfare claim to have from humans a kinder treatment than in nonhuman nature".[12]

Remove ads

Bibliography

Holmes Rolston III was author of eight books that have won acclaim in both academic journals and the mainstream press. They are:

- A New Environmental Ethics: The Next Millennium for Life on Earth (Routledge, 2012)

- Three Big Bangs: Matter-Energy, Life, Mind (Columbia University Press, 2011)

- Genes, Genesis and God (Cambridge University Press, 1999) Gifford Lectures

- Science and Religion: A Critical Survey (Random House 1987, McGraw Hill, Harcourt Brace; new edition, Templeton Foundation Press, 2006)

- Philosophy Gone Wild (Prometheus Books, 1986, 1989)

- Environmental Ethics (Temple University Press, 1988)

- Conserving Natural Value (Columbia University Press, 1994)

- Religious Inquiry: Participation and Detachment (Philosophical Library, 1985)

- John Calvin Versus the Westminster Confession (Richmond, VA: John Knox Press, 1972)

- "Care on Earth: Generating Informed Concern." Pages 205–245 in Paul Davies and Niels Henrik Gregersen, eds., Information and the Nature of Reality: From Physics to Metaphysics (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads