Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Honolulu Courthouse riot

Riot after election of King Kalākaua From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

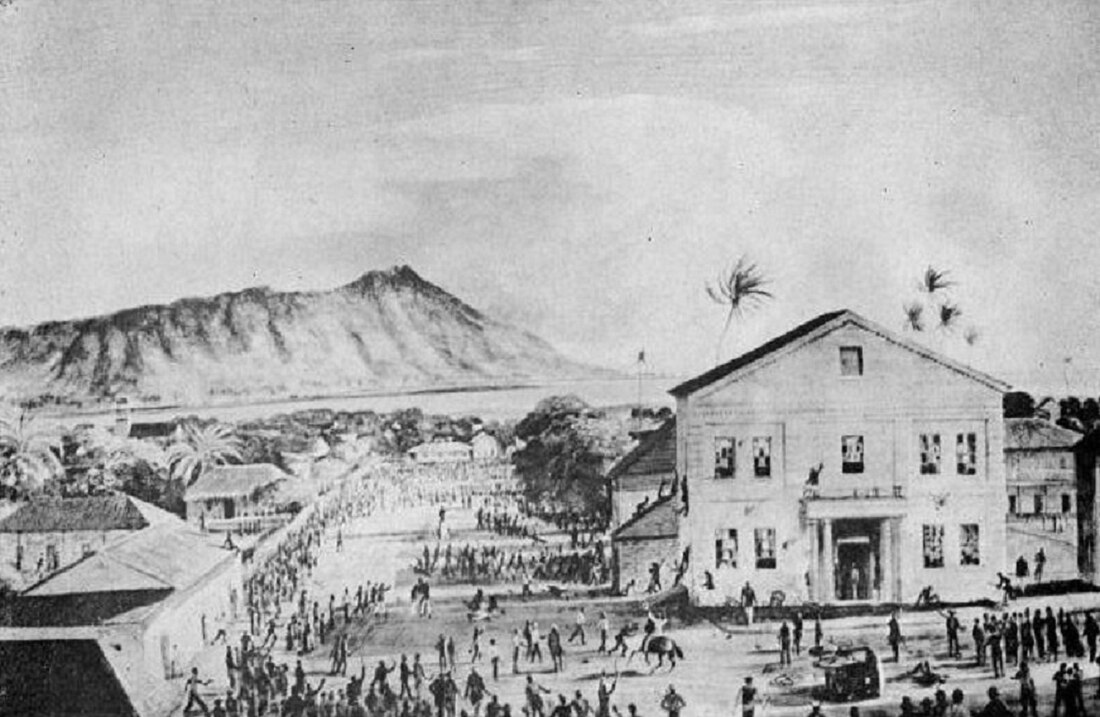

The Honolulu Courthouse riot, or the Election riot, occurred on February 12th, 1874, in the mid afternoon, when Hawaiian advocates of Queen Emma, known as Emmaites,[2] stormed the Honolulu Courthouse after American legislators announced David Kalākaua as King. The demonstrators were angered by the perceived legislature’s disregard for mass public, Native Hawaiian sentiment and by the growing influence of American businessmen and legislators in their sovereign nation’s affairs.[3] By late afternoon, the unrest was suppressed by 150 U.S. troops from the USS Tuscarora and USS Portsmouth, along with 70 British forces deployed by the British Consul General—further alienating Native Hawaiians from their political autonomy.[4] Kalākaua took the oath of office the following day without further opposition.[5][6] Over the next month, the Hawaiian Kingdom would make over 70 arrests but only half would be fully charged due to a lack of evidence, with 20 pleading guilty with unwavering, proud support for their Queen.[4][7] This election would later set the stage for further engrossment of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s sovereignty by the American businessmen and legislators through the 1887 Bayonet Constitution and eventual illegal overthrow.[8]

- This riot should not be confused with the 1852 Whaler Riot in Honolulu.

Remove ads

Royal Elections of 1874

Summarize

Perspective

King Lunalilo's Death and the 1864 Constitution

William Charles Lunalilo's rule began with his election on January 8th, 1873 and ended with his abrupt death on February 3rd, 1874.[9] With such a short reign, Lunalilo was unable to officially name a successor. Thus, the Constitution of 1864 called for another election.[10] Only three candidates were considered seriously:[11]

After Kamehameha V’s death, Princess Pauahi—having previously made clear that she did not wish to assume the throne—was removed from consideration as a candidate.[12] In the subsequent election, public enthusiasm overwhelmingly favored William Lunalilo, and the Legislature ultimately reflected that sentiment in its vote, even over David Kalākaua.[13] Because of this precedent, many Native Hawaiians believed that legislators—whether American-born or not—would again follow the will of the people and cast their votes for Queen Emma. The voting occurred on February 12, 1874, at the Honolulu Courthouse (located in Downtown Honolulu, Oʻahu). Each legislator checked a ballot box for either Queen Emma or David Kalākaua, whose name was rumored to have a incentivizing black heart on the back by the American businessmen. Kalākaua became king with a vote of 36-6.[14] The 1874 election was often framed as a choice between different visions for Hawaiʻi’s future—either a path of increased global engagement or the preservation of Native Hawaiian traditions, each associated with distinct American or British influences. Some scholars argue, however, that legislators’ decisions were shaped less by these ideological divides and more by questions of political power. Queen Emma had indicated that she intended to appoint a cabinet composed entirely of Native Hawaiians, while Kalākaua signaled that he would retain the current officeholders, including American-aligned legislators, thereby preserving their existing authority.[15]

Queen Emma's Campaign

Emma’s campaign relied heavily on her relation to royalty. Queen Emma claimed that Lunalilo planned to make her his successor but ran out of time due to his son’s, Prince Albert, unexpected death, making her the rightful heir.[12] Emma also highlighted her sacred Kamehameha blood as it was something Kalākaua would never be able to achieve. Such blood ties also gave Queen Emma the support of the Hawaiian Aliʻi as many ridiculed Kalākaua’s supposedly “high” ranking blood, some even calling him a “Bastard of Blossoms.”[4] Since Kalākaua was also heavily involved in American politics, Emma presented herself as a more pure Hawaiian and moral choice through her past civil services and Anglican beliefs.[9][16] However, some believed Emma was too pro-British rather than Native Hawaiian despite her motto being “Hawaiʻi for Hawaiians.”[17] It is also noteworthy that many Native Hawaiians historically perceived the British more favorably than the United States, in part because Britain (along with France) formally recognized the sovereignty of the Hawaiian Kingdom through the 1843 Anglo-Franco Proclamation. This declaration later became the basis for Lā Kūʻokoʻa (Hawaiian Independence Day), observed on November 28.[18] Queen Emma also made promises involving an all-Hawaiian cabinet (which made the American legislators nervous), major alterations to the Honolulu Police Department, and returning to a constitution similar to Kamehameha III’s.[15] To convince her people of her right to the throne, Queen Emma would make speeches across the islands, and if the election were to have been a popular vote by the Hawaiian people --her heavy supporters being called Emmaites or Queenities-- there is no doubt Emma would be victorious with her Kamehameha ties, but sadly, that was not the case, making the election of 1874 even more controversial and a turning point in Hawaiian elections. [2]

David Kalākaua's Campaign

Meanwhile, Kalākaua promised the revitalization of the people and their culture. In the 1873 election against William Lunalilo, Kalākaua refused American support as he thought they were planning to overthrow the Hawaiian government (which they were).[19][20] In response to Kalākaua’s lack of cooperation, many American businessmen publicly denounced Kalākaua through newspapers and private letters to other legislators and promoted William Lunalilo. A letter between a British government representative and an American businessman in 1873 stated, “Colonel Kalākaua would undoubtedly succeed by either rank or election, but the American party has made such a bitter enemy of him, that some of them publicly say they would resist by arms his succession.”[12]

However, by the 1874 election, the American businessmen knew the other candidate, Queen Emma, would never partner with them due to her anti-American sentiments from handling their negotiations with her husband and her pro-British ties that gave her enough foreign support. Thus, after numerous private meetings, Kalākaua went against his beliefs and partnered with those he used to defy the most to win the election as their (lack of) influence caused him to lose the previous year.[21][22][8] Although, some historians have speculated that Kalākaua simply underestimated what their influence would cost.[21] Other historians have theorized that Kalākaua simply had closer ties to the government officials voting as he worked with them while Queen Emma did not meet all of them.[22] Regardless, in exchange for their support in the newspapers, legislature, and businesses, Kalākaua promised them seats in his cabinet.[15] [9]

Nevertheless, Kalākaua focused his campaign on equity, liberty, and progress for Hawaiʻi in the modern world. The future King also promised to revitalize culture and ensure that the Hawaiian Kingdom would never be overthrown.[22]

Remove ads

The Election's Aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

When a King is usually announced, the awaiting crowd would jump for joy and sing in their new king’s honor; this was nowhere near the case for Kalākaua.[23] A few minutes past 3 pm on February 12, 1874, a group of legislators left the courthouse from the front doors to tell Kalākaua of the news and announce it to the public. There were small scattered cheers, however, the majority of the crowd began to shout in disdain.[24] Within seconds, rocks, sticks, and people flew at the leaving legislators and their awaiting carriage as one legislator, Major Moehonua, got trampled on and would have died if not for the British Commissioner, Major Wodehouse. As the carriage rushed off to tell Kalākaua of the results and the crowd, a few rioters followed as the majority turned their attention towards the courthouse. People began pounding on the doors and throwing anything they could at its windows until someone yelled to break in through the back. The back doors flew open as the rioters quickly broke in and began to infultrate the courthouse.[25][26] Once they were through with the courthouse, many rioters marched to Queen Emma’s summer palace to ask her to change the result or do something about the election as they saluted her.[27] When asked to calm the crowd Queen Emma remained locked up in her summer palace and refused to say a word. However, she did allow the legislators to write a letter on her behalf to stop the violence, although only her physical presence would make a difference. Additionally, Queen Emma’s letter had an underlying message to simply wait out Kalākaua’s reign and elect her in the next term which merely affirmed their beliefs of Kalākaua being an illegitimate king.[3][6]

When the Honolulu police were called to control the rioters, most officers took off their badges and joined in as they felt the same moral betrayal.[28] So, at 4:30 pm Kalākaua wrote to the British and American commissioners to ask for their naval soldiers to help end the protest. By sundown, 150 troops from the U.S. Tuscarora and Portsmouth and 70 from the British Consul General took control of the riots. The American soldiers controlled the Courthouse crowd and instantly made rioters run away from fear. However, the British troops’ arrival was originally celebrated as many Queenities thought they arrived to support their ally, Queen Emma. Despite the usual friendly ties, the British followed the request and dispersed the protest at Queen Emma’s Summer Palace. Within the following month, the Hawaiian Kingdom would make over seventy arrests but only charge half due to a lack of evidence, with twenty pleading guilty as they were not ashamed of their support for their queen.[2] [3][6][24] America's involvement in the riot also led to the establishment of the first United States Navy coaling and repair station in Pearl Harbor.[5][29]

Remove ads

Casualties

Summarize

Perspective

The riot, despite being largely unplanned, had a very strategic approach. Once the new King was announced, the news was not welcomed with its usually joyous cheers. Rather, shouts of disdain and anger erupted with rocks, sticks, and people beginning to fly through the air as legislators awaited their elite carriages.[30] Soon after, the back doors to the Courthouse opened and rioters attacked various papers, furniture, and windows. Yet, protestors left the clerk house and library untouched out of respect.[31] Thirteen legislators who voted for Kalākaua were severely injured including Samuel Kipi, J. W. Lonoaea, Thomas N. Birch, David Hopeni Nahinu, P. Haupu, C. K. Kakani, S. K. Kupihea, William Luther Moehonua, C. K. Kapule, D. Kaukaha, Pius F. Koakanu, D. W. Kaiue and R. P. Kuikahi. Two individuals not affiliated with the legislature were also injured: British subject John Foley, who tried to rescue Moehonua from the rioters, and a native partisan of Kalākaua's John Koii Unauna. No foreigners except Foley were harmed. Representative Lonoaea, the only fatality of the event, died as result of his injuries. Yet, the six who did vote for Queen Emma, most of whom were the minority Native Hawaiian representation, were kept safe.[11][27][7][32][3][31][33][34]

Effects leading to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom

Summarize

Perspective

Following the 1874 election and the subsequent Honolulu Courthouse riot, some American businessmen, who had already been discussing the removal of the Hawaiian monarchy with sympathetic U.S. political figures, interpreted the riot as evidence that more American influence in Hawaiʻi would be beneficial. Their efforts first focused on securing exclusive American access to Pearl Harbor as a naval station, officially justified as protection for the new king in the event of future disturbances, but also aligned with broader U.S. strategic interests in the Pacific and expanding American commercial dominance in the islands.[35][36] However, the American businessmen did not only see Pearl Harbor as a possible naval station. With the Hawaiian Kingdom having such a unique geographically desirable location for trade and pitstops, Pearl Harbor also became a capitalist's dream port. Thus, American business interests also negotiated to lift the U.S. tariffs on sugar(cane), later earning millions. Combined, these two factors caused enough influence to get King Kalākaua sign the Reciprocity Treaty of 1876. Although, despite getting exclusive access to trade and military services in Pearl Harbor, these Americans were unsatisfied and began pursuing the entire governance of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

On June 30, 1887, a group of armed members of the Honolulu Rifles, aligned with the American business men, forced Kalākaua to sign what became known as the Bayonet Constitution. This constitution effectively disabled the monarchy's powers and expanded the authority of the (American) legislature. Additionally, this constitution also imposed strict individual property and income requirements that disallowed majority of the Native Hawaiian voters from being eligible as most economic practices and advantages were shared communally.[37][38][39]

The 1874 election is often cited by historians as an early demonstration of the growing political leverage held by American residents, particularly in their support for Kalākaua and their role in suppressing the ensuing unrest. With Kalākaua on the throne, American businessmen saw an opportunity to further strengthen their position in Hawaiʻi, a process that ultimately culminated in the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893.

Remove ads

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads