Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

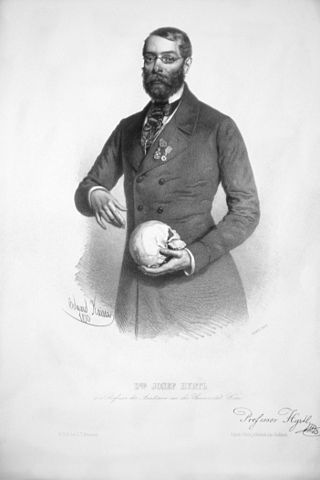

Josef Hyrtl

Austrian anatomist From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Josef Hyrtl (7 December 1810 – 17 July 1894) was an Austrian anatomist. His work in German, including the publication of Lehrbuch der Anatomie des Menschen in 1846, which was considered the German equivalent of Gray's Anatomy.[1]

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (December 2009) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Remove ads

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Hyrtl was born at Kismarton, Hungary (now Eisenstadt, Austria). His father was a musician in the orchestra of Count Esterhazy in Austria.[1] He received his preliminary education in his native town, and eventually went on to study medicine. He began his medical studies in Vienna in 1831.

It was as a teacher that Hyrtl exerted his greatest influence. Professor Karl von Bardeleben, a leader of anatomy in the nineteenth century, did not hesitate to say that in this Hyrtl was unequalled. His fame spread throughout Europe, and he came to be looked upon as the teaching pride of the University of Vienna.

In 1858, he was visited by George Eliot and her partner. In her journal, she wrote:

"Another great pleasure we had at Vienna—next after the sight of St. Stephen's and the pictures—was a visit to Hyrtl, the anatomist, who showed us some of his wonderful preparations, showing the vascular and nervous systems in the lungs, liver, kidneys, and intestinal canal of various animals. He told us the deeply interesting story of the loss of his fortune in the Vienna revolution of '48. He was compelled by the revolutionists to attend on the wounded for three days' running... His fortune in Government bonds was burned along with the house, as well as all his precious collection of anatomical preparations, etc. He told us that since that great shock his nerves have been so susceptible that he sheds tears at the most trifling events, and has a depression of spirits which often keeps him silent for days. He only received a very slight sum from Government in compensation for his loss."

In 1865, on the occasion of the celebration of the five-hundredth anniversary of the foundation of the University of Vienna, he was chosen rector in order that, as the most distinguished member of the university, he should represent her on that day. His inaugural address as rector had for its subject The Materialistic Conception of The Universe of Our Time. In this he argued that there was clear lack of logic in the materialistic view of the world and concluded:

"When I bring all this together it is impossible for me to understand on what scientific grounds is founded this resurrection of the old materialistic view of the world that had its first great expression from Epicurus and Lucretius. Nothing that I can see justifies it, and there is no reason to think that it will continue to hold domination over men's minds."

His brother Jakob Hyrtl (1799-1868) was a Viennese engraver, who bequeathed to his brother a skull attributed to Mozart. Josef Hyrtl examined the skull and bequeathed it to the city of Salzburg.[2] Hyrtl had another large collection of skulls, attributed to persons from Europe and the Caucasus region in an attempt to show significant differences in cranial features among individuals classified as white. This work was done to dispute the phrenologists at the time, who claimed certain cranial features were indicative of intelligence and personality. Today, 139 skulls from his collection are on display at the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[3]

In 1880 there was a magnificent celebration of Hyrtl's seventieth birthday, when messages of congratulation were sent to him from all the universities of the world.[citation needed] After retiring from his professorship he continued to do good work, his last publication being on Arabic and Hebraic elements in anatomy. On the morning of 17 July 1894, he was found dead in bed at his estate near Vienna.

Remove ads

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Hyrtl studied medicine at the University of Vienna from 1831 to 1835. In 1833, while he was still a student, he was named prosector in anatomy, and the preparations which this position required him to make for teaching purposes attracted the attention of professors as well as students.[4] His graduation thesis, Antiquitates anatomicæ rariores, was the first writing that he produced, which lead to much of his other work in the field of anatomy. After graduating in 1835, he became a professor of anatomy at the University of Prague.[1]

Upon graduating, he was assistant to Johann Nepomuk Czermak, a physiologist at the university. He would later become the curator of the museum.[citation needed] He added many specimens to the museum. As a student he set up a little laboratory and dissecting room in his lodgings, and his injections of anatomical material were greatly admired.[citation needed] He took advantage of his post in the museum to give special courses in anatomy to students and in practical anatomy to physicians. These courses were numerously attended.[citation needed]

In 1837, at 26, Hyrtl was offered the professorship of anatomy at the Charles University in Prague, and by his work there laid the foundation of his reputation as a teacher of anatomy.[5] There he completed his well-known textbook of human anatomy, which went through some twenty editions and has been translated into several languages. The chair of anatomy at the University of Vienna fell vacant in 1845. While satisfied with the opportunities for work in Prague, he applied for the appointment of chair at the insistence of close friends. He would go on to serve as Chair of the Department of anatomy at University of Vienna for 30 years.[4] Before his death he was to see this department of anatomy become one of the most important units of any medical school in the world.[citation needed]

In 1847, he published his Handbook of Topographic Anatomy, the first textbook of applied anatomy of its kind ever issued. He then published the book Manual of Dissection, as well as a manual on corrosion anatomy. These texts were practical guides for anatomists in dissecting and preserving remains.[4]

His monograph for the reform of anatomical terminology Onomatologia Anatomica (Vienna, 1880), attracted widespread attention.

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads