Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Bitola inscription

Medieval Bulgarian stone inscription From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

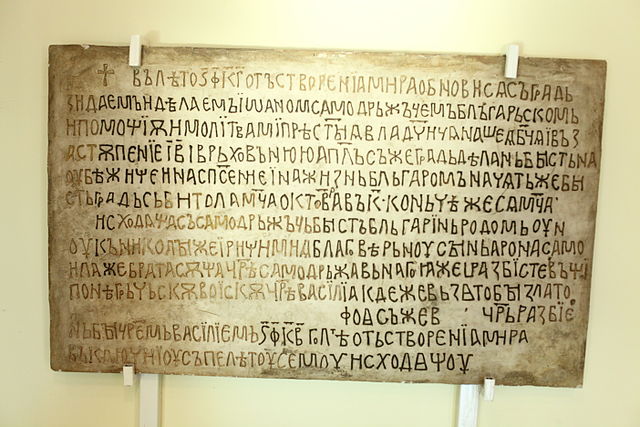

The Bitola inscription is a stone inscription from the First Bulgarian Empire written in the Old Church Slavonic language in the Cyrillic alphabet.[1] Currently, it is located at the Institute and Museum of Bitola, North Macedonia, among the permanent exhibitions as a significant epigraphic monument, described as "a marble slab with Cyrillic letters of Jovan Vladislav from 1015/17".[2] In the final stages of the Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria Ivan Vladislav was able to renovate and strengthen his last fortification, commemorating his work with this elaborate inscription.[3] The inscription found in 1956 in SR Macedonia, provided strong arguments supporting the Bulgarian character of Samuil's state, disputed by the Yugoslav scholars.[4]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The inscription was found in Bitola, SR Macedonia, in 1956 during the demolition of the Sungur Chaush-Bey mosque. The mosque was the first mosque that was built in Bitola, in 1435. It was located on the left bank of the River Dragor near the old Sheep Bazaar.[5] The stone inscription was found under the doorstep of the main entrance and it is possible that it was taken as a building material from the ruins of the medieval fortress. The medieval fortress was destroyed by the Ottomans during the conquest of the town in 1385. According to the inscription, the fortress of Bitola was reconstructed on older foundations in the period between the autumn of 1015 and the spring of 1016. At that time Bitola was a capital and central military base for the First Bulgarian Empire. After the death of John Vladislav in the Battle of Dyrrhachium in 1018, the local boyars surrendered the town to the Byzantine emperor Basil II. This act saved the fortress from destruction. The old fortress was located most likely on the place of the today Ottoman Bedesten of Bitola.[6]

After the inscription was found, information about the plate was immediately announced in the city. It was brought to Bulgaria with the help of the local activist Pande Eftimov. A fellow told him that he had found a stone inscription while working on a new building and that the word "Bulgarians" was on it.[7] The following morning, they went to the building where Eftimov took a number of photographs which were later given to the Bulgarian embassy in Belgrade.[8] His photos were sent through diplomatic channels to Bulgaria and were classified.

In 1959, the Bulgarian journalist Georgi Kaloyanov sent his own photos of the inscription to the Bulgarian scholar Aleksandar Burmov, who published them in Plamak magazine. Meanwhile, the plate was transported to the local museum repository. At that time, Bulgaria avoided publicizing this information as Belgrade and Moscow had significantly improved their relations after the Tito–Stalin split in 1948. However, after 1963, the official authorities openly began criticizing the Bulgarian position on the Macedonian Question, and thus changed its position.

In 1966, a new report on the inscription was published. It was done by the historian and linguist Vladimir Moshin,[9] a member of the Russian White émigré, living in Yugoslavia.[10] As a result, Bulgarian linguist Yordan Zaimov and his wife, historian Vasilka Tapkova-Zaimova, travelled to Bitola in 1968.[8] At the Bitola Museum, they made a secret rubbing from the inscription.[11] Zaimova claims that no one stopped them from working on the plate in Bitola.[8] As such, they deciphered the text according to their own interpretation of it, which was published by the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences in 1970.[12] The stone was locked away in the same year and a big Bulgarian-Yugoslav political scandal arose. The museum director was fired for letting such a mistake happen.[13] The Macedonian researcher Ugrinova-Skalovska published her translation of the inscription in 1975.

In 2023 the German linguist Sebastian Kempgen made an optical inspection of the plate. He discovered a superscript on the stone, which had already been reconstructed with linguistic methods. However Kempgen has shown that it actually exists, but it is a mystery why it has not been discovered before him. He has supposed that the superscript was made from a second stonecutter. Kempgen has also deduced that initially the inscription was carved at least on two stone plates, set together horizontally, and not on a single plate. Some letters from the current inscription were written on a lost plate, located left to the present block. Furthermore, it showed that the Zaimovs had incorrectly inserted missing letters, following lines 8, 9, and 10 of the inscription. The scans showed that no text is missing following these lines.[14] In a subsequent presentation, Kempgen described the Zaimovs' reconstruction as implausible, especially the existence of the first row written on a separate stone above. He noted that his study confirmed earlier criticism of the Zaimovs by Horace Lunt, especially that the text must have spilled over to a lost block on the left, although Lunt also supposed the existence of text written on one or more blocks at the top.[15][16]

Remove ads

Text

Summarize

Perspective

There have been preserved 12 rows of the inscription. The text is fragmentary, as the inscription was used as a step of the Sungur Chaush-Bey mosque. There are missing parts around the left and right edge and a large part on the lower left segment. In its current state, the following text is visible on the stone:[17]

1. ....аемъ и дѣлаемъ Їѡаном самодрьжъцемъ блъгарьско...

2. ...омощїѫ и молїтвамї прѣс͠тыѧ владч҃ицѧ нашеѧ Б͠цѧ ї в...

3. ...ѫпенїе І҃В҃ і врьховънюю апл҃ъ съ же градь дѣлань быст...

4. ...ѣж.... и на спс҃енѥ ї на жизнь бльгаромъ начѧть же і...

5. ...... градь с.....и..ола м͠ца ок...вра въ К҃. коньчѣ же сѧ м͠ца...

6. ...ис.................................................быстъ бльгарїнь родомь ѹ...

7. ...к..................................................благовѣрьнѹ сынь Арона С.....

8. ......................................................рьжавьнаго ꙗже i разбїсте .....

9. .......................................................лїа кде же вьзꙙто бы зл.....

10. ....................................................фоꙙ съ же в... цр҃ь ра.....

11. ....................................................в.. лѣ... оть створ...а мира

12. ........................................................мѹ исходꙙщѹ.

Text reconstructions

A reconstruction of the missing parts was proposed by Yordan Zaimov.[18] According to the reconstructed version, the text talks about the kinship of the Comitopuli, as well as some historical battles. Ivan Vladislav, claims to be the grandson of Comita Nikola and Ripsimia of Armenia, and son of Aron of Bulgaria, who was Samuel of Bulgaria's brother.[19] There are also reconstructions by the Macedonian scientist prof. Radmila Ugrinova-Skalovska[20] and by the Yugoslav/Russian researcher Vladimir Moshin (1894–1987),[21] In Zaimov's reconstruction the text with unreadable segments marked gray, reads as follows:[22]

[† Въ лѣто Ѕ҃Ф҃К҃Г҃ отъ створенїа мира обнови сѧ съ градь]

[зид]аемъ и дѣлаемъ Їѡаном самодрьжъцемъ блъгарьско[мь]

[въ Ключи ї ѹсъпе лѣтѹ се]мѹ исходꙙщѹ

[и п]омощїѫ и молїтвамї прѣс͠тыѧ владч҃ицѧ нашеѧ Б͠цѧ ї въз[]

[ст]ѫпенїе І҃В҃ і врьховънюю апл҃ъ съ же градь дѣлань бысть [на]

[ѹ]бѣ[жище] и на спс҃енѥ ї на жизнь бльгаромъ начѧть же

[бысть] градь с[ь Б]и[т]ола м͠ца ок[то͠]вра въ К҃. коньчѣ же сѧ м͠ца [...]

ис[ходѧща съ самодрьжъць] быстъ бльгарїнь родомь ѹ[нѹкъ]

[Ни]к[олы же ї Риѱимиѧ] благовѣрьнѹ сынь Арона С[амоила]

[же брата сѫща ц͠рѣ самод]рьжавьнаго ꙗже i разбїсте [въ]

[Щїпонѣ грьчьскѫ воїскѫ цр҃ѣ Васї]лїа кде же вьзꙙто бы зл[ато]

[...] фоꙙ съжев [...] цр҃ь ра[збїень]

[бы цре҃мь Васїлїемь Ѕ҃Ф҃К҃]В҃ [г.] лтѣ оть створ[енї]ѧ мира

Translation:

In the year 6523 since the creation of the world [1015/1016? CE], this fortress, built and made by Ivan, Tsar of Bulgaria, was renewed with the help and the prayers of Our Most Holy Lady and through the intercession of her twelve supreme Apostles. The fortress was built as a haven and for the salvation of the lives of the Bulgarians. The work on the fortress of Bitola commenced on the twentieth day of October and ended on the [...] This Tsar was Bulgarian by birth, grandson of the pious Nikola and Ripsimia, son of Aaron, who was brother of Samuil, Tsar of Bulgaria, the two who routed the Greek army of Emperor Basil II at Stipon where gold was taken [...] and in [...] this Tsar was defeated by Emperor Basil in 6522 (1014) since the creation of the world in Klyuch and died at the end of the summer.

According to Zaimov, there was additional 13th row,[note 1] at the upper edge. The marble slab bearing the inscription has on the top narrow surface holes and channels to fit metal joints. This is contrary to the Zaimov's claims that the inscription could have had another line on the top side.[23]

Dating

There is a single year mentioned on line 11 of the plate, which Moshin and Zaimov deciphered as 6522 (1013/1014). According to Zaimov, this date is relatively clearly visible,[24] although Moshin admitted that it has been rubbed.[25] Per the Slavist Roman Krivko, although the year carved in the inscription is unclear, it is correct to date it to the reign of Ivan Vladislav, who is mentioned as acting there, accordingly to the used present tense verb form.[26] The art historian Robert Mihajlovski one the other hand, puts the dating of the inscription in the historical context of its content, i.e., also during the reign of Ivan Vladislav.[27] The majority academic view, shared by a number of foreign and Bulgarian as well as some Macedonian researchers, is that the inscription is an original artefact, made during the rule of tsar Ivan Vladislav (r. 1015–1018), and is therefore the last remaining inscription from the First Bulgarian Empire with an roughly correct dating.[28] The Macedonian researcher to directly work on the plate in the 1970s, Radmilova Ugrinova-Skalovska, has also confirmed the dating and authenticity of the plate. According to her, Ivan Vladislav's claim to Bulgarian ancestry is in accordance with the Cometopuli's insistence to bound their dynasty to the political traditions of the Bulgarian Empire. Per Skalovska, all Western and Byzantine writers and chroniclers at that time, called all the inhabitants of their kingdom Bulgarians.[29]

American linguist Horace Lunt maintained that the year mentioned on the inscription is not deciphered correctly, thus the plate might have been made during the reign of Ivan Asen II, c. 1230.[30][31] His views were based on the photos, as well as the latex mold reprint of the inscription made by philologist Ihor Ševčenko, when he visited Bitola in 1968.[8] On the 23rd International Congress of Byzantine Studies in 2016, archaeologists Elena Kostić and Georgios Velenis based on their paleographic study,[32] maintained that the year on the plate is actually 1202/1203, which would place it in the reign of Tsar Ivan I Kaloyan of Bulgaria, when he conquered Bitola. They maintain, the inscription mentions some glorious past events to connect the Second Bulgarian Empire to the Cometopuli.[33][34] Some Macedonian researchers also dispute the authenticity or dating of the inscription.[35][36][37] According to the historian Stojko Stojkov, the most serious problem of the dating of the inscription from the 13th century is the impossible task of making any logical link among the persons mentioned in it, with the time of the Second Bulgarian Empire, and in this way the dating from the time of Ivan Vladislav is the most well-argued.[38] Velenis and Kostić confirmed too, that most of the researchers suppose that the plate is the last written source of the First Bulgarian Empire with an roughly accurate dating.[39] Per the historian Paul Stephenson, given the circumstances of its discovery, and its graphical characteristics, that is undoubtedly a genuine artifact.[40]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

The inscription confirms that Tsar Samuel and his successors considered their state Bulgarian,[41] as well as revealing that the Cometopuli had an incipient Bulgarian consciousness.[42][43] The proclamation announced the first use of the Slavic title "samodŭrzhets", meaning "autocrat".[44] The name of the city of Bitola is mentioned for the first time in the inscription.[45] The inscription indicates that in the 10th and 11th centuries, the patron saints of Bitola were the Holy Virgin and the Twelve Apostles.[46] The inscription confirms the Bulgarian perception of the Byzantines (Romaioi) as Greeks, including the use of the term "tsar", when referencing their emperors.[47]

After the collapse of Yugoslavia, the stone was re-exposed in the medieval section of the Bitola museum, but without any explanation about its text.[48] In 2006, the inscription was subject to controversy in the Republic of Macedonia (now North Macedonia) when the French consulate in Bitola sponsored and prepared a tourist catalogue of the town. It was printed with the entire text of the inscription on its front cover, with the word "Bulgarian" clearly visible on it. News about that had spread prior to the official presentation of the catalogue and was a cause for confusion among the officials of the Bitola municipality. The French consulate was warned and the printing of the new catalogue was stopped, and the photo on the cover was changed.[49] In 2021, a Bulgarian television team made an attempt to shoot the artefact and make a film about it. After several months of waiting and the refusal of the local authorities, the team complained to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Sofia. A protest note was sent from there to Skopje, after which the journalists received permission to work in Bitola.[50]

Footnotes

References

Notes

See also

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads