Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905

Unequal treaty subordinating Korea to Japan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

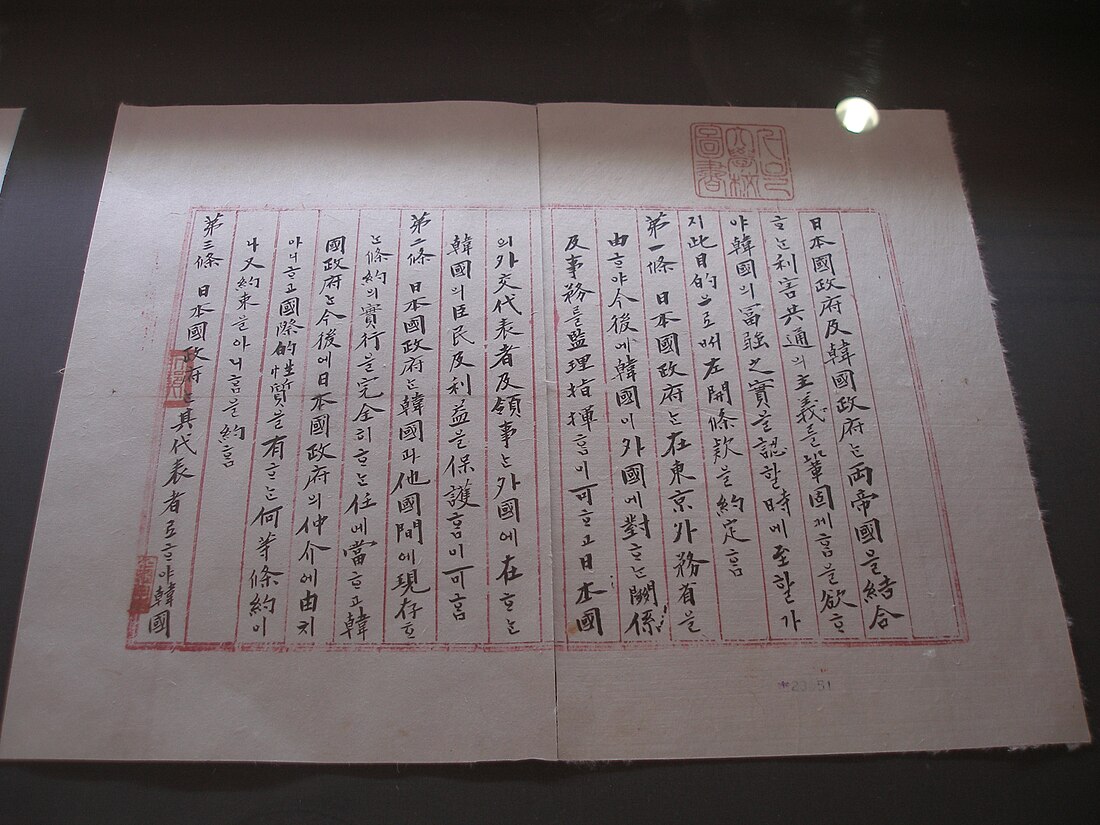

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905, also known as the Eulsa Treaty,[a] was made between delegates of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire in 1905. Negotiations were concluded on November 17, 1905.[4] The treaty deprived Korea of its diplomatic sovereignty and made Korea a protectorate of Imperial Japan. It resulted from Imperial Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905.[5]

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Beginning from the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876, a series of treaties were signed between Korea and Japan throughout the following decades. During the signing of the 1876 Treaty, Joseon Korea actively participated in the negotiation process, with the initial Japanese proposal of a most-favored nation clause ultimately omitted due to Korean demands.[6] However, Japanese demands for compensation after the 1882 Imo Incident led to the signing of the 1883 Treaty of Tax Regulations for the Japanese Trade and the Maritime Customs, which deprived Korea of its tariff autonomy over trade with Japan.[7] The Japanese victory over the Qing in the First Sino-Japanese War led to the complete withdrawal of Chinese forces in Korea, further consolidating Japanese influence over the peninsula.[8]

Following the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, Imperial Japanese forces were dispatched to occupy Seoul. Under Japanese military presence, the Korean government was forced to ratify the Japan–Korea Protocol on February 23, 1904.[9] The protocol stipulated that Japan may occupy and use strategically important locations in Korea to achieve military objectives.[10] In August of the same year, the First Japan–Korea Agreement was signed, which required that the Korean government accept financial and diplomatic advisors dispatched by Imperial Japan.[11] The agreement was utilized by Japan to bolster its exclusive dominance over Korea during the signing of the Taft–Katsura Agreement and the Second Anglo-Japanese Alliance.[12]

Remove ads

Signing of the treaty

Summarize

Perspective

With its victory over Russia and the subsequent withdrawal of Russian influence from Korea, Japan sought to deprive the Korean Empire completely of its diplomatic rights and render it a protectorate.[13] In a 27 October 1905 cabinet meeting, the Japanese government agreed on eight provisions regarding the signing of a second treaty to acquire absolute authority over Korea's foreign affairs. Specifics of the treaty were drafted on a separate document, which was transmitted to Seoul the following day.[14]

On 2 November 1905,[14] President of the Privy Council Itō Hirobumi was dispatched to Korea as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to lead negotiations.[15] Itō arrived in Seoul on 9 November 1905. Accompanied by Deputy Ambassador to the Kingdom of Korea Hayashi Gonsuke, Itō delivered a letter from the Emperor of Japan to Gojong, Emperor of Korea, attempting to arrange a meeting with him. However, Gojong initially refused, citing his illness.[16] Gojong acquiesced to Itō's demands on 15 November, however,[16] when Itō ordered Japanese troops to encircle the Korean imperial palace.[citation needed] Throughout their meeting, Gojong and Itō argued for over three hours, with Gojong questioning whether the signing of the agreement would render Korea's status into that of the colonized nations of Africa. When Itō requested that Gojong order his foreign minister to commence negotiations, he refused, arguing that such matters were subject to the approval of the Korean Privy Council (jungchuwon) via government procedure.[15]

Negotiations between the Korean cabinet and the Japanese delegates began on the 16th. Seven members of the State Council (Uijeongbu)—Prime Minister Han Kyu-seol, Minister of the Army Yi Geun-taek, Minister of the Interior Yi Ji-yong, Minister of Agriculture, Commerce, and Industry Gwon Jung-hyeon, Minister of Finance Min Yeong-gi, Minister of Education Yi Wan-yong, and Minister of Justice Yi Ha-yeong—along with former Prime Minister Shim Sang-hoon, were summoned by Itō to his residence, where sessions were held.[16] Deputy Ambassador Hayashi arranged separate negotiations with Minister of Foreign Affairs Pak Chesun in the Japanese legation, where he proposed a rough negotiations agenda.[17][16] In a separate meeting, however, Gojong and the Korean ministers decided that the agenda would not be submitted to a State Council meeting.[17]

On the morning of 17 November, Hayashi once again summoned the Korean ministers to the Japanese legation, where they again refused to sign any agreement in terms of government procedure. Hayashi then proceeded to Jungmyeongjeon hall in Gyeongungung palace with the ministers, where an Imperial Conference (어전회의; 御前會議) was held.[18] When the conference once again refused to sign the treaty, Hayashi sent a messenger to Itō around 6 in the evening, who was then waiting with Field Marshal Hasegawa Yoshimichi in Daegwanjeong, the headquarters of the Japanese army stationed in Korea.[17] Two hours later,[18] Itō and Hasegawa arrived, now accompanied with Japanese military police, at Jungmyeongjeon Hall. Itō resumed negotiations and confronted each of the ministers individually, asking their opinion on the agreement.[19] He further pressured the cabinet with the implied, and later stated, threat of bodily harm, to sign the treaty.[20] Han Kyu-seol and Min Yeong-gi expressed explicit objection to the signing of the treaty, while Yi Ha-yeong and Gwon Jung-hyeon expressed a weak opposition. However, the rest of the cabinet reluctantly agreed to the treaty under conditions that minor revisions are made, with Gwon later reversing his stance.[19]

With the approval of five out of the eight ministers present, Itō declared the agreement valid.[21] Around 1:30 AM, November 18, the seal of the Korean Minister of Foreign Affairs was affixed.[22]

Treaty provisions

The treaty, which only consisted of five articles,[19] transferred most of the diplomatic rights of the Korean Empire under the jurisdiction of the Japanese government, depriving Korea of its diplomatic sovereignty[23][24] and effectively making it a protectorate of Imperial Japan.[25] The treaty prohibited the Korean government from signing any treaty or agreement of "international nature" without the supervision of Japan. Under Article 3 of the treaty, a high-ranking official, titled the Resident-General,[26] was to be dispatched to Seoul for the handling of diplomatic affairs, where he would be given the right to visit the Korean Emperor on private occasions.[19]

The provisions of the treaty took effect on 17 November 1905.[27] It was to be put into effect until "Korea becomes wealthy and strong", under a clause proposed by Yi Wan-yong.[19][22]

Remove ads

Aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

As a consequence, the Korean Empire had to close all of its diplomatic administrations abroad, including its short-lived legation in Beijing,[28] and its legation in Washington, D.C.[29] Foreign legations in Korea began withdrawing and allocating their operations to their corresponding Japanese legations, with France being the last country to close its Korean legation.[citation needed]

In February 1906, the Residency-General was established in Seoul,[19] with Itō Hirobumi appointed as the first Resident-General.[30]

Gojong's efforts for rescission

Upon learning of its signing, Emperor Gojong commenced efforts to nullify the treaty, mainly seeking international assistance from countries that had established diplomatic relations with Korea.[32] On 22 November, four days after the signing, Gojong sent an undisclosed telegram to Homer Hulbert in the United States and urged him to convince the American government that the treaty was signed under threat of force without his consent and was thus invalid,[19] but without success.[33] In 29 January 1906, he handed Douglas Story, a reporter from the Tribune, a secret letter urging a joint foreign protection of Korea from Japanese influence. The letter was successfully smuggled to China by Story, but was dismissed by the British Minister in Peking Ernest Satow.[34] In May 1906, Gojong drafted another letter to Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, which was received by the German Foreign Office but was never presented to the Kaiser.[35]

In 1907, Gojong sent three emissaries to the Second Hague Peace Conference in utmost secrecy to further promote the cause of Korean sovereignty. The envoys arrived at the Hague in June 1907, but were barred from entering the conference and ultimately failed to garner significant support from the great powers.[36] When news of the envoys reached Japan, Gojong was forcibly abdicated. Subsequently, the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907 was signed on 24 July 1907, between Itō Hirobumi and Yi Wan-yong, transferring authority over Korea's internal affairs to the Resident-General.[32]

Protests against the treaty

Several high-ranking Korean officials protested against the treaty. Head of the Royal Bodyguard (시종무관장; 侍從武官長) Min Yeong-hwan demanded that the treaty be abolished, and the five ministers executed.[31] On November 30, Min committed suicide in protest when his demands were not met. Special secretary of the Department of the Royal Household (특진관; 特進官) and former Right State Councilor Cho Byeong-se committed suicide the following day.[37]

Local yangbans and commoners formed righteous armies known as Eulsa uibyeong (을사의병; 乙巳義兵; lit. Eulsa righteous army).

On 20 November 1905, in an editorial titled I Wail Bitterly Today, editor-in-chief of the Hwangsŏng sinmun Chang Chi-yŏn accused the Korean ministers who had agreed to the treaty for giving up the "integrity of a nation which has stood for 4,000 years... and the rights and freedom of twenty million people."[38]

Remove ads

Modern contentions

Summarize

Perspective

While the Treaty of 1905 has been confirmed to be "already null and void" by the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea,[40] the legality of the treaty at the time of its signing remains controversial. The overarching argument within Korean academics is that the treaty was never valid in the first place, as it was independently negotiated under a threat of force by the Korean ministers without the approval of Gojong, the plenipotent head of state.[41] Conversely, multiple Japanese studies have concluded that the treaty was sanctioned under his consent, emphasizing Gojong's active partaking throughout the ratification process.[42] The veracity of several documents provided by these studies as evidence have been questioned by Korean academics.[42]

In 18 February 2005, Kim Sam-ung (김삼웅), director of the Independence Hall of Korea, declared the Treaty of 1905 "void ab inito" (원천무효).[29] In a joint statement on June 23, 2005, officials of South Korea and North Korea reiterated their stance that the Eulsa treaty is null and void on a claim of coercion by the Japanese.[citation needed]

In Korea, the five ministers who approved of the Treaty (Yi Wanyong, Yi Geun-taek, Yi Ji-yong, Park Chesun, and Gwon Jung-hyeon) are widely referred to as the Five Eulsa Traitors.

Remove ads

See also

- Japan–Korea Treaty of February 1904

- Japan–Korea Agreement of August 1904

- Japan–Korea Agreement of April 1905

- Japan–Korea Agreement of August 1905

- Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907

- Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910

- Anglo-Japanese Alliance

- Taft–Katsura Agreement

- Treaty of Portsmouth

- Root–Takahira Agreement

- Unequal treaty

- Governor-General of Korea

- I Wail Bitterly Today – famous editorial about the treaty

Remove ads

Footnotes

- The word Eulsa or Ulsa[1] derives from the Sexagenary Cycle's 42nd year in the Korean lunisolar calendar, in which the treaty was signed.[2] As the treaty lacked an official title,[3] it has been identified by several other names, including Second Japan–Korea Convention (第二次日韓協約, 제2차 한일협약), Eulsa Restriction Treaty (乙巳勒約; 을사늑약), Eulsa Protection Treaty (乙巳保護条約, 을사보호조약),[3] and Korea Protection Treaty (韓国保護条約).[citation needed]

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads