Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Keraites

Former Turco-Mongol tribal confederation in Mongolia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Keraites (also Kerait, Kereit, Khereid, Kazakh: керейт; Kyrgyz: керей; Mongolian: ᠬᠡᠷᠢᠶᠡᠳ, Хэрэйд; Nogai: Кереит; Uzbek: Kerait; Chinese: 克烈, Persian: کرایت[16]) were one of the five dominant Turco-Mongol tribal confederations (khanates) in the Altai-Sayan region during the 12th century. They had converted to the Church of the East (Nestorianism) in the early 11th century and are one of the possible sources of the European Prester John legend.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

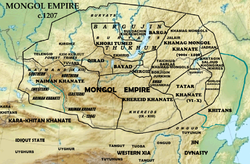

Their original territory was expansive, corresponding to much of what is now Mongolia. Vasily Bartold (1913) located them along the upper Onon and Kherlen rivers and along the Tuul river.[17] They were defeated by Genghis Khan in 1203 and became influential in the rise of the Mongol Empire, and were gradually absorbed into the succeeding Mongol khanates during the 13th century.

Remove ads

Name

In English, the name is primarily adopted as Keraites, alternatively Kerait, or Kereyit, in some earlier texts also as Karait or Karaites.[18][19]

One common theory sees the name as a cognate with the Mongolian хар (khar) and Turkic qarā for "black, swarthy". There have been various other Mongol and Turkic tribes with names involving the term, which are often conflated.[20]

According to the early 14th-century work Jami' al-tawarikh by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani,[21][22]:

Chapter three

It is related that in ancient times there was monarch who had eight (seven) sons, all of whom were dark-skinned. For which reason they were called Kerait. After that, with the passage of time, the separate offspring of each of the sons took on name and epithet. The division among whom the monarchy is held until today is know simply as the Keraite. a special name and nickname. The other sons became the servants to the brother who was monarch, and there was no monarch found among them."

Other researchers also suggested that the Mongolian name Khereid may be an ancient totem name derived from the root Kheree (хэрээ) for "raven".[23]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Origins

This article may contain an excessive number of citations. (September 2025) |

The Keraites first entered history as the ruling faction of the Zubu, a large confederacy of tribes that dominated Mongolia during the 11th and 12th centuries and often fought with the Liao dynasty of north China, which controlled much of Mongolia at the time.

The names and titles of early Keraite leaders suggest that they were speakers of Turkic languages, and Togrul is a Turkic rather than a Mongol name. Toghrul's father and grandfather bore the Turkic title buiruk ('commander'); the title of the Keraite princess, Dokuz-khatun, is Turkic, as is the title 'Yellow Khan' under which one Keraite leader is know.[24][25][26][27] Building on this discussion of names and titles, Russian researcher Zolkhoev noted that Mongols not infrequently bore names of Turkic origin, but he stressed that such linguistic evidence alone is insufficient to establish a Turkic origin for the Keraites.[28] In contrast Amanzholov wrote names of the Mongols before the 13th century were not Turkic.[29]

Zolkhoev claims the majority of scholars and researchers classify the Keraites as a Turkic people[30]. A number of European and Asian scholars classified them as a Turkic people.[31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59] Scholars like Erica C. D. Hunter[60], Paul Ratchnevsky[61], Christoph Baumer[62], Zhou Qingshu[63], René Grousset[64], Ian Gilman[65], Yekemingghadai Irinchin[66], Hans-Joachim Klimkeit[67], John Man[68][69], John Saunders[70], Tu Ji[71], Maria Czaplicka[72], Klaus Schwarz[73], Steven Runciman[74], Tjalling Halbertsma[75], Manfred Taube[76], Paul Pelliot[77], Wilhelm Baum[78], Svat Soucek[79], Pavel Poucha[80], Marie Favereau[81], Yevgeny Kychanov[82], Alexander Kadyrbaev[83], Marat Mukanov[84], Mukhamedzhan Tynyshpaev[85], Lidija Viktorova[86], Jean-Paul Roux[87], Nikolai Serdobov[88], Nikolai Aristov[89], Muratkhan Kani[90], Rudolf Kaschewsky[91], Türükoğlu[92], Gabzhalilov, Talas Omarbekov[93], Sarsen Amanzholov[94] Alkey Margulan[95] classified them as Turkic people.

Rashid al-Din Hamadani write in his Jami' al-tawarikh[96]:

Chapter three

"The Turkic tribes that have also had separate monarchs and leaders but do not have a close relationship to the tribes mentioned in the previous division or to the Mongols yet they are close to them in physiognomy and language".

Each of these nations has had monarch or leader, their yurts dwelling places were delineated, and each has branched off into various subdivisions. These nations are held in high esteem at this time by other Turks previously mentioned and by the Mongol Turks because Genghis khan's family, who are monarchs of Mongols, conquered and subdued them through God's might. In ancient times these nations were of more importance and mightier than any other groups of Turks, and they had powerful monarchs. The stories of each of these nations wil be mentioned separately.

They had powerful monarchs from within their own tribes, and at that time they possessed more might and power than other nations within those borders. Christian missionary activity reached them, and they converted to that religion. They are a sort of Mongol. Their dwelling place is along the Onon and Kerulen Rivers, the land of Mongolia, which region is near the frontier of Cathay. They had many disputes with many tribes, particularly with the Naiman".

The Kerait are mentioned under the chapter title "The Turkic tribes that have also had separate monarchs and leaders but do not have a close relationship to the tribes mentioned in the previous division or to the mongols yet are close to them in physiognomy and language".[97][98] Irinchin who favored Turkic origin for Keraite note, Rashid ad-Din in his classification distinguishes them from the Mongol-speaking tribes , grouping them together with tribes of predominantly Turkic origin , with the exception of only the Tanguts.[a] Amanzholov and Mukanov wrote Rashid ad-Din classifies the Keraits among the Turks, and in his classification distinguishes them from the Mongols and listed them Next to the Turkic tribes.[99][100] In contrast Semenov and Petrushevsky note, Rashid al-Din uses the term “Turks” broadly for the nomadic tribes of Central Asia of very diverse origins, including peoples speaking not only Turkic but also Mongolic, Tangut, and Tungusic languages. Thus, for him “Turks” is not an ethno-linguistic label so much as a socio-cultural one - “nomads.”[101] Petrushevsky further argues that it can be stated with a high degree of probability that a number of polities - Tatars, Kerait, Naiman, Jalayir, Suldus, Barlas, Merkit, and Oirat - were Mongolic-speaking rather than Turkic-speaking in the 13th century.[102] In contrast Nikolai Aristov wrote from the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate to the time of Genghis Khan, Mongolia, with the exception of its extreme northeastern part, where the Mongols appeared, continued to be occupied by the Turks, he further classified the Keraite, Naiman and Öngüt as Turkic Tribes.[103]

In the "Yuan chao mi shi" there is an indication of their kinship with the Mongols.[104] But this kinship in "Yuan chao mi shi" is not between Keraites and Mongols as peoples, It only talks about relationships between Keraite ruler Wang khan and Mongol ruler Yesugei.[b][105]

Amanzholov and Mukanov wrote Abul-Ghazi classified the Keraites as Turkic people and distinguishes them from the Mongols.[106][107]

Ushnitsky claims that most researchers, consider the Keraites to be of Mongolic origin[108]. Mongolian origin is supported by Vasily Bartold,[109] Lev Gumilev,[110] Ilya Pavlovich Petrushevsky,[102] Gennady Avlyaev,[111] Boris Zolkhoev,[112] Vadim Trepavlov,[113] Shoqan Walikhanov,[114] Sergei Klyashtorny, Tursun Sultanov,[115] Tao Zongyi,[116] Aleksei Rakushin,[117] Urgunge Onon,[118] Boris Vladimirtsov[119] and others. Vladimirtsov suggested that the Mongolian written language first arose among the Kerait and Naiman tribes before the era of Genghis Khan.[120] Russian researcher Avlyaev believes that the Kerait tribal confederation included, in addition to the Mongolic component represented by the Keraits themselves, Turkic-Uyghur and Samoyedic elements.[121] In the work of Tao Zongyi, a historian of the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties, the Keraites are listed among the '72 Mongol peoples.' According to Zolkhoev, this clear designation as a subgroup of the Mongols in the Yuan period, consistent with Rashid al-Din’s "Compendium of Chronicles" where they are described as a 'clan of the Mongols,' strongly suggests that the Kerait tribe belonged to the Mongolic-speaking substratum.[122]

At the same time, Ushnitsky himself described the Keraites as a mysterious tribe whose ethnic affiliation is unclear and is unlikely ever to be definitively established. According to him, most likely, they consisted of groups of different origin, united by the adoption of Nestorian Christianity as a state religion.[123] There are also such hypotheses regarding the Keraites: Yevgeny Kychanov considered them to be part of the Yenisei Kyrgyz[82][124], while Saishiyal believed that they had a Tungusic origin.[125][126]

They are first noted in Syriac Church records which mention them being absorbed into the Church of the East around 1000 by Metropolitan Abdisho of the Merv ecclesiastical province.

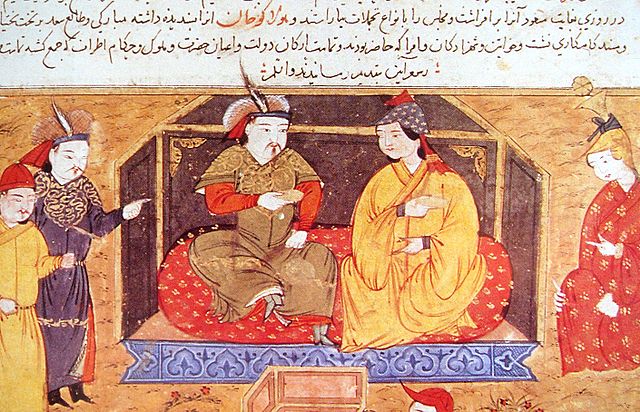

Khanate

After the Zubu broke up, the Keraites retained their dominance on the steppe until they were absorbed into the Mongol Empire. At the height of its power, the Keraite Khanate was organized along the same lines as the Naimans and other powerful steppe tribes of the day. A section is dedicated to the Keraites by Rashid al-Din Hamadani (1247–1318), the official historian of the Ilkhanate, in his Jami' al-tawarikh.

The people were divided into a "central" faction and an "outer" faction. The central faction served as the khan's army and was composed of warriors from many different tribes with no loyalties to anyone but the Khan. This made the central faction more of a quasi-feudal state than a genuine tribe. The "outer" faction was composed of tribes that pledged obedience to the khan, but lived on their own tribal pastures and functioned semi-autonomously. The "capital" of the Keraite khanate was a place called Orta Balagasun, which was probably located in an old Uyghur or Khitan fortress.[citation needed]

Markus Buyruk Khan was a Keraite leader who also led the Zubu confederacy. In 1100, he was killed by the Liao. Kurchakus Buyruk Khan was a son and successor of Bayruk Markus, among whose wives was Toreqaimish Khatun, daughter of Korchi Buiruk Khan of the Naimans. Kurchakus' younger brother was Gur Khan. Kurchakus Buyruk Khan had many sons. Notable sons included Toghrul, Yula-Mangus, Tai-Timur, and Bukha-Timur.[citation needed] In union with the Khitan, they became vassals of the Kara-Khitai state. [citation needed]

After Kurchakus Buyruk Khan died, Ilma's Tatar servant Eljidai became the de facto regent. This upset Toghrul who had his younger brothers killed and then claimed the throne as Toghrul khan (Mongolian: Тоорил хан, romanized: Tooril khan) who was the son of Kurchakus by Ilma Khatun, reigned from the 1160s to 1203.[citation needed] His palace was located at present-day Ulan Bator and he became blood-brother (anda) to Yesugei. Genghis Khan called him khan etseg ('khan father'). Yesugei, having disposed of all Tughrul's sons, was now the only one in line to inherit the title khan.

The Tatars rebelled against the Jin dynasty in 1195. The Jin commander sent an emissary to Timujin. A fight with the Tatars broke out and the Mongol alliance defeated them. In 1196, the Jin Dynasty awarded Toghrul the title of "Wang" (king). After this, Toghrul was recorded under the title "Wang Khan" (Chinese: 王汗; pinyin: Wáng Hàn). When Temüjin, later Genghis Khan, attacked Jamukha for the title of Khan, Toghrul, fearing Temüjin's growing power, plotted with Jamukha to have him assassinated.

In 1203, Temüjin defeated the Keraites, who were distracted by the collapse of their coalition. Toghrul was killed by Naiman soldiers who failed to recognize him.

Mongol Empire and dispersal

Genghis Khan married the oldest niece of Toghrul, Ibaqa, and then two years later divorced her and had her remarried to the general Jürchedei. Genghis Khan' son Tolui married another niece, Sorghaghtani Bekhi, and his son Jochi married a third niece, Begtütmish. Tolui and Sorghaghtani Bekhi became the parents of Möngke Khan and Kublai Khan.[127] The remaining Keraites submitted to Timujin's rule, but out of distrust, Timujin dispersed them among the other Mongol tribes.[citation needed]

Rinchin protected Christians when Ghazan began to persecute them but he was executed by Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan when fighting against his custodian, Chupan of the Taichiud in 1319.

Keraites arrived in Europe with the Mongol invasion led by Batu Khan and Mongke Khan. Kaidu's troops in the 1270s were likely mostly composed of Keraites and Naimans.[128]

From the 1380s onward, Nestorian Christianity in Mongolia declined and vanished, on the one hand due to the Islamization under Timur and on the other due to the Ming conquest of Karakorum. The remnants of the Keraits by late 14th century lived along the Kara Irtysh.[129] These remnants were finally dispersed in the 1420s in the Mongol-Oirat wars fought by Uwais Khan.[130]

Remove ads

Clans

According to the early 14th-century work Jami' al-tawarikh by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani,[131][132]:

The Keraites consist of many tribes and groups, all of which followed ong khan, as follows: Keraite, The jirqin, The Tongqayit, Saqiyat, The Toba'ut, The Albat.

Nestorian Christianity

Summarize

Perspective

The Keraites were converted to the Church of the East, a sect of Christianity, early in the 11th century.[127][133][134] Other tribes evangelized entirely or to a great extent during the 10th and 11th centuries were the Naiman and the Ongud.

Hamadani stated that the Keraites were Christians. William of Rubruck, who encountered many Nestorians during his stay at Mongke Khan's court and at Karakorum in 1254–1255, notes that Nestorianism in Mongolia was tainted by shamanism and Manicheism and very confused in terms of liturgy, not following the usual norms of Christian churches elsewhere in the world. He attributes this to the lack of teachers of the faith, power struggles among the clergy and a willingness to make doctrinal concessions to win the favour of the Khans. Contact with the Catholic Church was lost after the Islamization under Timur (r. 1370–1405), who effectively destroyed the Church of the East. The Church in Karakorum was destroyed by the invading Ming dynasty army in 1380.

The legend of Prester John, otherwise set in India or Ethiopia, was also brought in connection with the Eastern Christian rulers of the Keraites. In some versions of the legend, Prester John was explicitly identified with Toghril,[127] but Mongolian sources say nothing about his religion.[135]

Conversion account

An account of the conversion of this people is given in the 12th-century Book of the Tower (Kitab al-Majdal) by Mari ibn Suleiman, and also by 13th-century Syriac Orthodox historian Bar Hebraeus where he names them with the Syriac word ܟܹܪܝܼܬ "Keraith").[136][137]

According to these accounts, shortly before 1007, the Keraite Khan lost his way during a snowstorm while hunting in the high mountains of his land. When he had abandoned all hope, a saint, Sergius of Samarkand, appeared in a vision and said, "If you will believe in Christ, I will lead you lest you perish." The king promised to become Christian, and the saint told him to close his eyes and he found himself back home (Bar Hebraeus' version says the saint led him to the open valley where his home was). When he met Christian merchants, he remembered the vision and asked them about the Christian religion, prayer and the book of canon laws. They taught him the Lord's Prayer, Te Deum, and the Trisagion in Syriac. At their suggestion, he sent a message to Abdisho, the Metropolitan of Merv, for priests and deacons to baptize him and his tribe. Abdisho sent a letter to Yohannan V, Patriarch of the Church of the East in Baghdad. Abdisho informed Yohannan V that the Khan asked him about fasting and whether they could be exempted from the usual Christian way of fasting since their diet was mainly meat and milk.

Abdisho also related that the Khan had already "set up a pavilion to take the place of an altar, in which was a cross and a Gospel, and named it after Mar Sergius, and he tethered a mare there and he takes her milk and lays it on the Gospel and the cross, and recites over it the prayers which he has learned, and makes the sign of the cross over it, and he and his people after him take a draft from it." Yohannan replied to Abdisho telling him one priest and one deacon was to be sent with altar paraments to baptize the king and his people. Yohannan also approved the exemption of the Keraites from strict church law, stating that while they had to abstain from meat during the annual Lenten fast like other Christians, they could still drink milk during that period, although they should switch from "sour milk" (fermented mare's milk) to "sweet milk" (normal milk) to remember the suffering of Christ during the Lenten fast. Yohannan also told Abdisho to endeavor to find wheat and wine for them, so they can celebrate the Paschal Eucharist. As a result of the mission that followed, the king and 200,000 of his people were baptized (both Bar Hebraeus and Mari ibn Suleiman give the same number).[24][138]

Remove ads

Legacy

After the final dispersal of the remaining Keraites settling along the Irtysh River by the Oirats in the early 15th century, they disappear as an identifiable group. There are various hypotheses as to which groups may partially have been derived from them during the 16th or 17th century. According to Tynyshbaev (1925), their further fate was closely linked to that of the Argyn.[139] The name of the Qarai Turks may be derived from the Keraites, but it may also be connected to the names of various other Central Asian groups involving qara "black".[140] Kipchak groups such as the Argyn Kazakhs and the Kyrgyz Kireis have been proposed as possibly in part derived from the remnants of the Keraites who sought refuge in Eastern Europe in the early 15th century.[141] Keraites are also part of 92 tribes of Uzbeks[142]. According to the "Altan Tobchi", the Keraites were apparently part of the ancient Oirat confederation[143]. Keraites were also part of Bashkirs and Nogais.[144][145]

Remove ads

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads