Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

King's Law

1665 Danish law From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The King's Law (Danish: Kongeloven) or Lex Regia (also called the Danish Royal Law of 1665[1]) was the absolutist constitution of Denmark and Norway from 1665 until 1849 and 1814, respectively. It established complete hereditary and absolute monarchy and formalized the king's absolute power, and is regarded the most sovereign form[2] of all the European expressions of absolutism.[3][4][5] Some scholars of legal history assert that with Europe's least circumscribed form of absolutism, Denmark "may be considered the most absolute of all the absolute European monarchies."[6] It is the only formal constitution of any absolute monarchy,[7][8] and has therefore been the subject of considerable historical and academic attention.[9][10][11]

The King's Law comprises 40 articles and is divided into seven main chapters.[12][13] Articles 1 to 7 determine the royal absolute power, and the following articles contain rules on the king's authority and guardianship, on the king's accession and anointing, on the indivisibility of the kingdoms, on princes and princesses, on the king's duty to maintain absolute monarchy, and on the succession.[14]

In Denmark, the majority of the King's Law was replaced in 1849 by the new constitution, when Denmark became a parliamentary monarchy, although two articles of the King's Law are still applicable:[15][16] firstly Article 21, requiring the king's permission for the departure and marriage of princes and princesses, and secondly Article 25, according to which princes and princesses of the blood can be criminally and civilly prosecuted only on the king's orders.[14][17] This legal immunity is one of the most extensive in Europe[18] and has, amid recurring debate, shielded Danish royals from prosecution in cases involving, traffic violations, misconduct, and refusal to testify, among other things.[19][20][21][22]

The King's Law was read aloud during the king's coronation and anointing, but not officially published until 1709. Two original copies are currently accessible to the public, one at the Danish National Archives, and one at Rosenborg Castle (both in Copenhagen).[23] The copy at Rosenborg is King Frederik X's private property and is stored in the treasury vault along with the Danish Crown Regalia.[23]

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

After Denmark-Norway's catastrophic defeat by Sweden in the Dano-Swedish War (part of the Second Northern War) in 1660, an assembly of the estates of the realm (Danish: stænderforsamling) was summoned to Copenhagen by king Frederik III, above all in order to reorganize the kingdom's finances.[24] The burghers especially felt that the nobility had not lived up to its responsibilities (securing the army and defence of the kingdom), which were the justification for its privileges.[6] In this tense situation, negotiations for various reforms went forward until the beginning of October, but in vain.[10] On 11 October, the king ordered the city gates of Copenhagen to be closed so that no one could leave without the permission of the king and the mayor. Under intense pressure from the burghers of Copenhagen and through the threat that force might be employed against the Danish nobility, the estates were persuaded to "agree" to transfer absolute power to the crown, Frederik III.[25]

Completion

This new constitution (lex fundamentalis) for Denmark–Norway, which in 40 articles gave the king absolute power and all the rights of the sovereign, and also fixed the rules of succession, was influenced by contemporary European political thinking, especially by Jean Bodin and Henning Arnisaeus.[26]

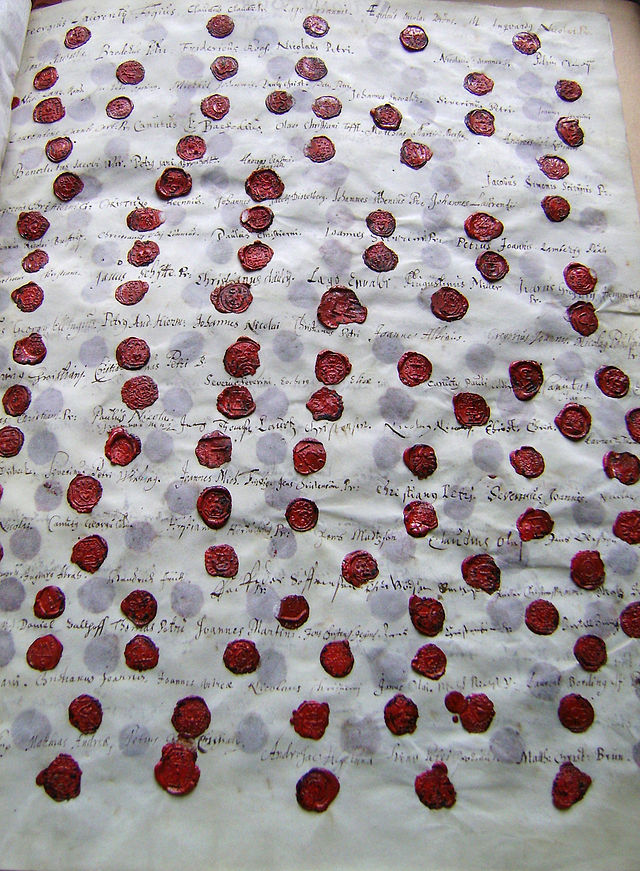

When the constitutional discussions were completed, Schumacher rewrote the new King's Law in duplicate. One was placed in the Privy Council's Archives (Danish: Gehejmearkivet), i.e. in the State Archives (afterwards the Danish National Archives), another at Rosenborg Castle together with the state crowns (Christian IV's and Christian V's) and the other crown regalia. Moreover, the fact that Schumacher had a very large part of the credit for the law is evident from the fact that he countersigned it.[27]

Remove ads

Text and publication

Summarize

Perspective

The King's Law was published during the reign of Frederick IV, engraved throughout, the royal copy bound in red velvet elaborately embroidered in gold and silver thread with the king's monogram in the centre.[28]

Essentially, the King's Law stated that the King was to be 'revered and considered the most perfect and supreme person on the Earth by all his subjects, standing above all human laws and having no judge above his person, [...] except God alone'.[29] It effectuated the divine right of kings.[30]

A copy of the King's Law published by the Royal Danish Library, may be found at here.

Summary of the King's Law

The law dictated the three primary duties of the Danish absolute monarch:[31]

- To worship God, according to the Augsburg Confession (Lutheranism).

- To keep the kingdoms (Denmark-Norway) undivided.

- To ensure that the King's power did not deteriorate.

In exchange, the king was given unrestricted rights and was, according to the constitution, responsible only to God.[31] For example, he had the unrestrained legislative and executive power, he could declare war and make peace, and was the head of the church.[23][32]

Remove ads

Repealing

Denmark

In the epilogue to the June Constitution of 1849, the King's Law was repealed except for Articles 27 to 40 (on the succession) and Articles 21 and 25 (concerning the royal princes and princesses).[35] The King's law's provisions on the succession were repealed by the Act of Succession of 1953.

Although the King's Law was repealed, many of the king's prerogatives of the Danish Constitution have a precursor in the King's Law. Thus, several of the prerogatives are directly to be found in the King's Law.[36]

Remaining articles still in force

Summarize

Perspective

The two articles of the King's Law that remain in force concern a range of regulations governing the members of the Danish Royal Family and the internal rules of the Royal Household, and were expressly retained when the other provisions of the law were repealed. The intent behind their retention was to preserve the monarch’s traditional authority over internal affairs of the royal household, and they are regarded as a form of dynastic or domestic law (Danish: huslov) within the new constitutional framework.[21][37]

The Danish Ministry of Justice has repeatedly confirmed the continued validity of the provisions, which have been applied on various occasions, and they constitute some of the oldest unamended legal provisions still in force in Danish legal history.[16][38]

Article 21: marriage and travel restrictions

Article 21 of the King's Law prohibits the marriage, travel or foreign enlistment of members of the royal family without the king's permission.[21] It reads:

No Prince of the Blood, who resides here in the Realm and in Our territory, shall marry, or leave the Country, or take service under foreign Masters, unless he receives Permission from the King.

The rules governing the marriage of individuals in line to the throne were further restricted in the Act of Succession of 1953, which also requires the approval of the Council of State and results in automatic forfeiture of the right of inheritance if permission is not granted.[39] Article 21 is therefore considered obsolete with regard to the question of marriage.

Article 25: legal immunity

Article 25 concerns the immunity of members of the royal family. It prescribes:

They [the princes and princesses] should answer to no inferior Judges, but their first and last Judge shall be the King, or to whomsoever He decrees.

In effect, this means that members of the Danish royal family enjoy complete legal immunity from both criminal prosecution and civil litigation, an exemption that applies uniformly across all levels of the judiciary. This immunity corresponds to the monarch’s own protection under Section 13 of the Constitution, which declares the King’s person inviolable and free from legal responsibility. As a consequence, royal family members cannot be compelled to stand trial or testify before any court. However, the reigning monarch retains the discretionary authority to waive this immunity in exceptional cases. They remain some of the broadest royal immunity provisions in Europe.[38][40]

While the royal houses in other European monarchies also enjoys similar rights and privileges, these are generally far less extensive than those that have persisted since the era of absolutism in Denmark. Thus, in Norway, the rule requiring the King's consent for legal proceedings against members of the royal family applies only to cases that concern "their persons" whereas in Sweden as well as in the United Kingdom, the dynasts are subject to the ordinary courts, just like all other citizens.[18]

Article 25 not only shields the royal family from ordinary judicial proceedings but also vests the sovereign with broad and unilateral powers to enforce and discipline members of the royal family. In 1945, for instance, King Christian X expelled his sister-in-law, Princess Helena (wife of Prince Harald), because she was a Nazi sympathiser.[41]

The provision has been invoked or cited in various high-profile and publicised incidents since the 20th century. In 1998, Prince Joachim and Princess Alexandra declined to testify in a criminal case against a former servant, leading to the collapse of prosecution due to royal immunity.[42] The stipulations of Article 25 were referenced in prenuptial agreements concluded for Prince Joachim’s two marriages (to Alexandra in 1995 and Marie in 2008), as well as for Crown Prince Frederik and Mary in 2004. According to the prenups, Queen Margrethe was to preside over all separation negotiations. However, during Prince Joachim and Alexandra's divorce in 2004, the Queen transferred this authority to the Prime Minister's Office to avoid any suspicion of bias or favouritism towards her son.[43] Historically, the Danish monarch has maintained broad and unilateral powers of separation, as when King Christian X appointed arbitrators in 1935 to preside over the divorce between Prince Erik and Lois Frances Booth (thus bypassing the ordinary courts).[43]

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Prince Gorm of Denmark, a collateral prince and captain in the Royal Danish Army, was twice implicated in a serious misconduct case. He allegedly violated the Danish penal code's provisions on sexual offences (Danish: sædelighedsforbrydelse), offenses carrying multi-year prison sentences. Those provisions (§§220/225) indicated particularly serious sexual misconduct involving abuse of authority.[44] The first incident was quietly resolved with a transfer. In the second, in 1953, soldiers threatened to shoot him, prompting fears of mutiny.[44][45] He was summoned to Amalienborg Palace, and after a heated controversy with King Frederik IX, he was dismissed, although “with pension and in grace”. He was never charged or investigated because of his immunity.[46] The military authorities and the Court Marshal's office covered up the case, and because[46] the topic was taboo, it was only superficially covered in the press.

Traffic offences

In multiple traffic-related incidents and offences, Article 25 has prevented legal sanctions such as fines, disqualification from driving, or similar penalties.[21] According to established practice, it is the reigning monarch who exercises disciplinary authority over royal family members in such cases.[47]

In 1953, for instance, King Frederik IX revoked Prince René of Bourbon-Parma’s driving privileges within Denmark for a period of one year following a drunk driving incident in Østerbro, where he damaged several cars and was taken into custody after a heated pursuit.[46] Prince René was married to Princess Margaret, the King's first cousin.[47] Before that, in 1931, Prince Erik of Denmark hit a police officer in Roskilde with his car. The question of liability and speeding penalty was dismissed ‘in accordance with king's law'.[48]

Traffic-related infractions by then-Crown Prince Frederik and Prince Joachim, including speeding and reckless driving, likewise went unprosecuted as a result of immunity provisions.[49][20][50] For instance, in November 2004, Prince Joachim was filmed driving at allegedly 160 km/h on Helsingørmotorvejen, but police dropped the case due to his immunity. Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen noted that royal family members "[are] required to obey the laws of the country", but conceded that only the Queen can discipline or lift immunity.[51]

Waiver of immunity

In various cases, the monarch has waived the immunity of certain members of the royal family. For example, when Prince Axel became director of the East Asiatic Company in 1934, King Christian X revoked his civil immunity (but not criminal), to make him legally accountable and bring potential compensation claims before the ordinary courts.[52] Similarly, members of the royal family have had their immunity in professional or commercial activities waived.[53][54] For instance, Prince Joachim, had his immunity relinquished by Queen Margrethe II in connection with his commercial activities as landowner of Schackenborg Castle in Southern Denmark.[55]

Members of the Royal Family cannot individually renounce their immunity, whether generally or in relation to a specific case.[52]

Extent of people covered

The full scope of individuals encompassed by the broad immunity provisions set forth in Article 25 has been the subject of scholarly debate within the field of constitutional law. Article 25 explicitly limits its application to “Princes or Princesses of the Blood”. A strictly textual interpretation suggests that this refers solely to the direct patrilineal descendants of the monarch and the reigning dynasty, currently the House of Glücksburg. In more conventional interpretations, however, the provision is understood to apply to the royal house (Danish: Kongehuset) at least in a narrow sense.[18]

The Danish constitutional scholars Knud Berlin and Alf Ross, as well as the Danish encyclopedia Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon, all consider the term to refer primarily to members of the royal house "in the strict or narrow sense". By convention, that includes the Queen consort, the Queen dowager, the Crown Prince, and other agnatic descendants eligible for the throne as their spouses or widows, but excluding royals affiliated with foreign dynasties.[56] That would explicitly exclude the deposed Greek Royal Family, who continue to style themselves Princes of Greece and Denmark, as well as the Norwegian Royal Family, both of which are members of the House of Glücksburg.[18]

In 2022, Queen Margrethe II stripped four of her grandchildren (the children of Prince Joachim) of their princely title and status. They consequently lost their royal immunity, and are no longer considered part of the Royal House. Similarly, all Counts of Rosenborg have lost their immunity.[57]

Criticism and debate

Discussions about the continued validity of the two articles in the King's Law, particularly Article 25, arise periodically and resurface occasionally when members of the royal family commit offences for which ordinary citizens would otherwise be punished. Especially the retention of royal immunity has caused recurring legal debate in modern Danish constitutional scholarship. Critics have characterized the provision as anachronistic and incompatible with democratic legal norms, while supporters emphasize that royal immunity is integral to the monarchy.[22]

While public and political debate over the relevance of Article 25 has intensified in recent decades, including calls for reform, successive governments have refrained from initiating legislative revision. An opinion poll in 2020 showed that 38% of respondents in Denmark opposed continued royal immunity, whereas 43% supported its preservation.[22]

Scholarly commentary

In a 2001 interview, then constitutional law professor and current President of the Supreme Court, Jens Peter Christensen, criticised Article 25 of the King's Law as “a relic of absolutism” and argued that its scope should be limited to the monarch alone; in his view, Parliament could adopt a modern statutory “house law” to delimit the legal position of other members of the royal family without constitutional amendment.[58]

Remove ads

Christian VII

Christian VII of Denmark ascended the Danish throne in 1766 as absolute monarch. Throughout his reign he suffered from various physiological illnesses including schizophrenia, which made him insane.[59] As the King's Law had no physical or mental incapacity provisions, Christian could not officially be considered insane, as such a view would have constituted lèse-majesté (Danish: Majestætsfornærmelse).[59] As a result, he could not be legally dismissed or forced to abdicate, nor could a regency be enacted. During the mental illness attacks of Christian's first cousin, George III of Great Britain, Britain's parliamentary system was not met with a similar problem. Christian married Caroline Matilda of Great Britain, George's sister, in 1766.[13]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads