Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Lead climbing

Technique of rock climbing From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Lead climbing (or leading) is a technique in rock climbing where two climbers work together to ascend a climbing route. The 'lead climber' — who is doing the climbing — clips the rope to pieces of protection as they ascend. The 'second' (or 'belayer') stands at the base of the route controlling the other end of the rope, which is called belaying (e.g. if the 'lead climber' falls, the 'second' locks the rope). The term distinguishes between the two roles and the greater effort and increased risk of the role of the 'lead climber'.[1]

Leading a route is in contrast with the alternative climbing technique of top roping, where even though there is still a 'second' belaying the rope, the 'lead climber' faces no risk in the event of a fall and does not need to clip into any protection as the rope is already anchored to the top of the route (e.g. if they fall they will just hang from the static rope). Leading a climbing route is a core activity in rock climbing, and first ascents (FA) and first free ascents (FFA) of new routes must be done via lead climbing.

Lead climbing can be performed as free climbing, in either a traditional climbing or a sport climbing format — leading a traditional climb is a much riskier and physically demanding exercise for the climber. Competition lead climbing is a sport-climbing format that is part of the Olympic sport of competition climbing. Lead climbing can also be performed as aid climbing. The term is not applied to free solo climbing, as the free solo climber is alone and thus there is no need to distinguish the role of 'leader' from the 'second'.

Remove ads

Description

Summarize

Perspective

The two phases of leading a climb

1. 'Leader' (top, climbing) being belayed by their 'second' (below, static)

2. 'Leader' (top, static) now belaying their 'second' (below, climbing)

Leading a climb involves a 'lead climbing pair'. The 'lead climber' — the person initially doing the climbing (see image .1) — will have a rope attached to their harness that they will clips into points of protection as they ascend the route. The 'second' (or 'belayer'), remains static, standing at the base of the route controlling the other end of the rope, which is called belaying. The 'second' will use a belay device to attach the rope to their harness from which they can 'pay-out' the rope as the 'lead climber' ascends, but with which they can lock the rope if the 'lead climber' falls. Once the 'lead climber' has reached the top (see image .2), they create a fixed anchor so they can act as the 'belayer' (from above), controlling the rope while the 'second' ascends. The 'second' will unclip the rope from the protection as they ascend.[2][3]

If the pair are leading a traditional climbing route, the 'lead climber' must also arrange and insert 'removable protection' into the rock face as they climb the route (the 'second' will take it out as they ascend). However, if they are leading a sport climbing route, the protection will already be installed via pre-drilled bolts into the rock face.[2][3][4] Leading a traditional route is therefore a riskier and more physically demanding undertaking than leading a sport-climbing route of the same grade.[5]

If a 'lead climber' falls they will drop at least twice the distance to their last point of protection. For example, if the 'lead climber' is 3 metres (10 ft) above their protection when they fall — and the 'belayer' immediately locks the rope — they will drop 6 metres (20 ft) until the rope holds them.[5] This aspect makes lead climbing a more physically demanding activity than top roping, where the 'lead climber' is immediately held by the top-rope if they fall. Note that when the 'second' is climbing and is belayed by the 'lead climber' from above, they are effectively top-roping and the rope will immediately hold them if they fall. This puts less onus on the skills of the 'second' climber, and they can also be partially 'pulled' up the route by the 'lead climber' if needed.[2][3]

Leading a climb requires good communication between the 'lead climber' and the 'second' who is doing the belaying. The 'lead climber' will want to avoid the 'second' holding the rope too tightly, which can create rope drag that acts as a downward force on the 'lead climber'. However, where the 'lead climber' feels that a fall is imminent (e.g. on a very hard section), they will want the 'second' to take in any slack in the rope to minimize the length of their drop in the event that they fall.[2][3]

First ascent and redpoint

The act and desire to 'lead' a climbing route is related to the definition of what is a first ascent (FA), or first free ascent (FFA) in climbing. The technical grades assigned to climbing routes are based on the climber 'lead climbing' the route, and not top-roping it. If a climber wants to test themselves at a specific technical grade, or set a new technical grade milestone in the sport, then they must 'lead climb' the route.[2][3]

Before the arrival of sport-climbing in the early-1980s, traditional climbers frowned upon FFAs where the 'lead climber' had practiced the route beforehand on a top-rope (called headpointing). The arrival of sport-climbing led to the development of the redpoint as the accepted definition of a lead climbing FFA, which includes the practices of headpointing. Where a 'lead climber' can redpoint a climbing route on their first attempt and without any prior knowledge, it is called an onsight, which is considered a distinctive redpoint, and is recorded in grade milestones and climbing guidebooks.[6][7]

Remove ads

Risk

Summarize

Perspective

Aside from the specific risks involved in placing the temporary protection equipment when leading traditional climbing routes — and making sure that it won't rip out in the event of a fall — the 'lead climber' also needs to manage other general risks when they are leading a route, such as:[2][3][5]

- Runout is the distance from the 'lead climber' to the last point of protection. In any fall, the 'lead climber' falls at least twice the distance of the runout (and sometimes more if the climbing rope flexes, or if the belayer does not immediately lock the rope and lets more rope 'pay-out'). The greater the runout, the greater the total distance in any fall, and the greater the risk to the 'lead climber'. Some leads involve runouts where any fall will result in a "ground-fall" (also called "hitting the deck").[5][8]

- Hitting obstacles during falls. Ironically, extreme climbing routes tend to be very overhanging (e.g. Realization or Silence), and thus where a 'lead climber' falls, they naturally avoid hitting any obstacles on the way downce until the rope holds. In contrast, on easier climbing routes, there is a greater chance of the 'lead climber' hitting against obstacles on the rock face as they fall, thus risking injury.[5][8]

- Back-clipping is where the rope is clipped into a quickdraw in such a way that the lead climber's end runs underneath the quickdraw carabiner as opposed to over the top of it; if the 'leader' falls, the rope may fold directly over the carabiner gate causing it to open with dangerous consequences.[5][9]

- Z-clipping is where the 'lead climber' grabs the rope below an already clipped quickdraw and clips it into the next quickdraw, resulting in a "zig-zag" shape of the rope on the wall, which can create immense rope drag making further progress impossible until it is fixed.[5][9]

- Turtling is where one of the 'lead climber's' limbs is behind the rope when they fall, which can result in the climber being "flipped" upside down (i.e. like a turtle on its back), which can then eject the climber from their harness, which is a serious event.[5][9]

Remove ads

Equipment

Summarize

Perspective

'Lead climbers' on traditional climbing routes carrying their climbing protection on their climbing harness whilst being belayed by their 'second' who is standing below.

Regardless of the particular type of format that the 'lead climber' is undertaking (i.e. traditional, sport, or aid), they will require a harness attached to one end of a dynamic kernmantle rope (usually via a figure-eight knot). Their 'second'—who will be belaying—will use a mechanical belay device that is clipped into the climbing rope and which 'pays-out' the rope as needed as the 'lead climber' ascends the route, but which can immediately grip the rope tightly in the event that the 'lead climber' falls.[2][3]

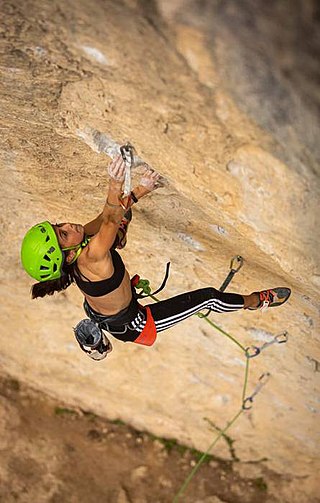

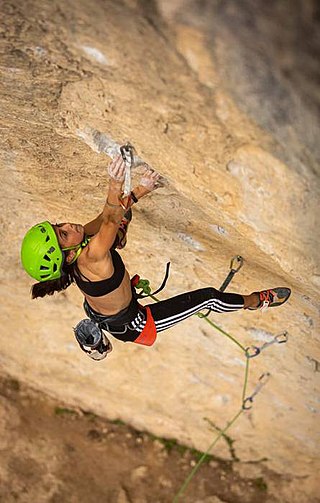

'Lead climbers' on sport climbing routes about to clip their ropes into quickdraws, which are already hanging from pre-installed bolts, with their belayer standing below.

Where the 'lead climber' is following a traditional-climbing format, they will need to carry an extensive range of protective equipment (often referred to as a 'climbing rack' and is usually worn around the waist being attached to the climbing harness) such as nuts, hexcentrics and tricams (known as "passive" protection), and/or spring-loaded camming devices (or "friends", and known as "active protection").

Where the 'lead climber' is following a sport-climbing format, they only need to carry quickdraws (which they will also attach to their climbing harness) that they will clip into the pre-drilled bolts along the sport route.[2][3][10]

Some indoor climbing walls provide in-situ mechanical lead auto belay devices enabling the climber to lead the route but belayed by the device. Typical versions belay the lead climber from above so the climber is essentially top roping the route, and thus does not need to carry any climbing protection.[11][12]

Multi-pitch leading

Summarize

Perspective

Longer climbing routes (e.g. such as in big wall climbing), are usually led in series of multiple pitches of circa 35–50 metres (115–164 ft) in length. In multi-pitch leading, the two climbers can swap the roles of 'lead climber' and 'second' on successive pitches. The 'second' also needs to be comfortable working from a hanging belay, and both need to be familiar with the process for swapping between roles safely and efficiently without becoming accidentally unattached from the protection.[13] Given that average pitch length will be longer, and that the weather potentially poorer, both climbers need to communicate clearly, and know the climbing commands.[14]

On long but easier routes, the lead climbing pair may use simul climbing, whereby both climbers simultaneously ascend the route. The 'lead climber' acts like on a normal lead climb, however, the 'second' does not remain belaying in a static position, but instead also climbs, removing/unclipping the protection equipment of the 'lead climber'. Both climbers are tied to the rope at all times, and both make sure that there are several points of protection in-situ between them. Simul climbing is performed on terrain both climbers are very comfortable on as any fall can still be very serious. In simul climbing, the stronger climber will ofen go second, wbich is in contrast to normal lead climbing.[15]

Remove ads

Competition lead climbing

The arrival of the safer format of sport climbing in the early 1980s led to a rapid development in the related sport of competition lead climbing.[16] The first major international lead climbing competition was held in Italy at Sportroccia in 1985.[16] By the late 1990s, competitive lead climbing was joined by competition bouldering, and competition speed climbing in what was to become the annual IFSC Climbing World Cup and biennial IFSC Climbing World Championships.[16] Competition lead climbing first appeared as an event in the 2020 Summer Olympics for men's and women's medal events; it was structured in a format consisting of a single "combined" event of lead, bouldering and speed climbing.[17][18]

Remove ads

See also

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lead climbing.

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads