Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

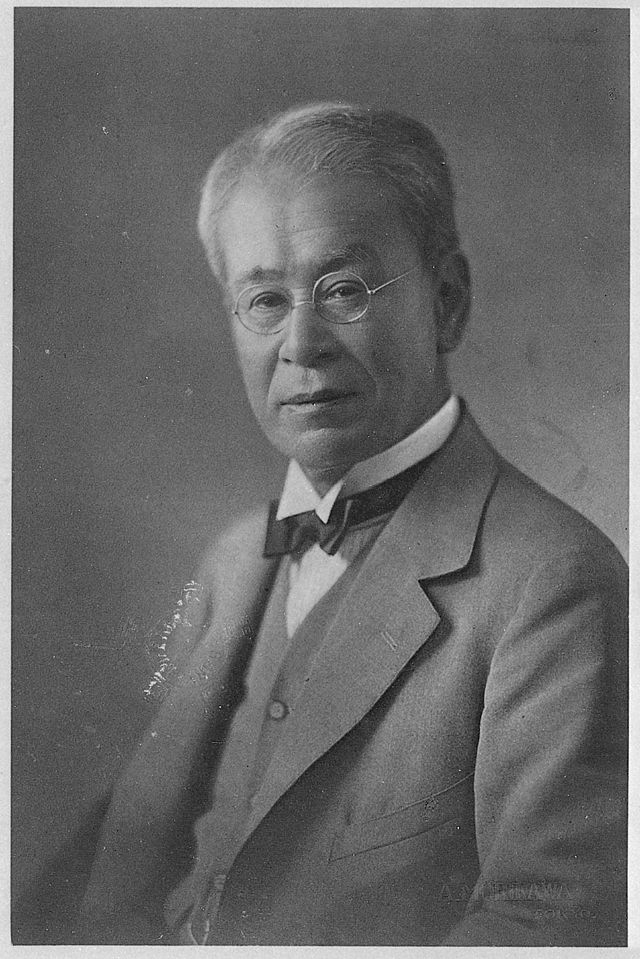

Tomitaro Makino

Japanese botanist (1862-1957) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Tomitaro Makino (牧野 富太郎, Makino Tomitarō; April 24, 1862 – January 18, 1957) was a pioneer Japanese botanist noted for his taxonomic work. He has been called "Father of Japanese Botany",[1][2][3][4] having been one of the first Japanese botanists to work extensively on classifying Japanese plants using the system developed by Linnaeus. His research resulted in collecting more than 500,000 specimens[a], many of which are represented in his Makino's Illustrated Flora of Japan. Despite having dropped out of grammar school, he eventually attained a Doctor of Science degree, and his birthday is remembered as Botany Day in Japan.

Remove ads

Legacy

In total, Makino named over 2,500 plants, including 1,000 new species and 1,500 new varieties.[5][6][b] In addition, he discovered about 600 new species.[9]

After his death in 1957, his collection of approximately 400,000 specimens was donated to Tokyo Metropolitan University which has housed the collection at its Makino Herbarium .[8] Around the same time, Makino Botanical Garden opened in his native Kōchi on Mount Godai.[8] His home in Higashiōizumi, Nerima-ku, Tokyo was converted into the Makino Memorial Garden and Museum.[8]

He was also named an Honorary Citizen of Tokyo.[10]

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Tomitaro Makino was born 22 May 1862[11][c] in Sakawa, Kōchi to a prestigious sake brewer and household goods purveyor called Kishiya (岸屋). The privileged merchant family was entitled to a surname and sword-bearing.[12][13] His parents died during his early childhood (father Sahei (佐平) at age 3, mother Kusu (久壽) at age 5) and he lost his grandfather Kozaemon (小左衛門) at age 6, leaving his step-grandmother Namiko (浪子) to raise him. His name was also changed from Seitarō (誠太郎/成太郎) given at birth to Tomitaro around the time he lost his close kins.[12][17]

In 1872 at age 10 (or 1871, age 9[18]), he began attending a terakoya (so-called "temple school") run by Doi Kengo (土居謙護) in his home neighborhood,[d][19][20] later transferring to Itō-juku, run by Confucian scholar Itō Ranrin where he was taught alongside Four Books and Five Classics Chinese learning, arithmetic and calligraphy as well.[21]

In 1873 at age 11 (or 1872, age 10[18]), he cross-enrolled at Meikōkan (名教館) but since Itō was also part of the faculty here, he soon quit Itō-juku.[20][22][23] Since Meikōkan was a gōgaku (lit. "village"[24]), it had the pretense of education for samurai extended to commoners,[24] and was mostly attended by samurai family pupils. A classmate here was Hiroi Isami (later dubbed "father of harbor engineering").[25] This school did not stick to Chinese scholarship, but taught geography, astronomy, and physics, western-style, using Fukuzawa Yukichi's Sekai kunizukushi and Kawamoto Kōmin's Kikai kanran kōgi (気海観瀾広義, Observations of the Billowing Waves of Air and Sea , Enlarged) as textbooks.[26][22] Around this time, Makino became acquainted with a certain westernization enthusiast named Manabe, who not only recommended the adoption of zangiri hairstyle (without topknot), but coaxed Makino into joining the same English study society of which he was already a member. This study group had hired two English linguists from Kōchi city, and borrowed English books from the prefectural government office. Thus Makino got his start in gaining literacy in English.[27]

Meikōkan became Sakawa Elementary School due to gakusei school reform,[28][14] and Makino attended only 2 years before dropping out (though this is misleading, since he had attained the top level for "lower elementary school" thus nearly graduating[30]), and began to study botany in self-taughte manner.[28] He states that he expected to succeed in his family brewery at the time, and was "not contemplating at all" about entering a life of academia.[31][29][32] He spent a brief period of this time in his youth supporting the Freedom and People's Rights Movementin his hometown Tosa Province.[6][e]

He foisted the duty of operating the brewery onto his grandmother and senior manager (bantō) while he lived a dilettante's life as he pleased.[32] At age 15, he took up the teaching post at Sakawa Elementary, resigning after 2 years[31][34][35] in 1880 (at age 17/18), when he moved to Kōchi city to attend Goshō Gakusha (五松学舎).[36] But since this institution concentrated heavily on Chinese learning, it did not please him to attend any of its lectures,[37] and delved into studying geography and botany which were the subjects that interested him.[37] Around this time, he was also diligently making handwritten copies of herbal medicinal scholar Ono Ranzan's critique Honzō kōmoku keimō (本草綱目啓蒙) (i.e. "Elucidation of Bencao Gangmu), which developed his knowledge of herbal pharmacology a.[38] But his trip to Kōchi did have its windfall, which was getting the acquaintance of Koichirō Naganuma (永沼小一郎).[37] Naganuma taughta at Kōchi Shihan Gakkō (precursor to the Kōchi University Education Department), who was so proficient in English as to privately translate such books as Robert Bentley's Botany and show the manuscripts to Makino.[37] Thus Makino widened his knowledge of western botanical scholarship, learning who the authorities in the field were. Makino has state in his autobiography: "My knowledge of botany owes greatly to Naganuma-sensei".[39]

Makino self-published his first academic paper in a journal he created in 1879 (around the end of his elementary schoolteacher career, before leaving for Kōchi). The journal was called Hakubutsu sōdan (博物叢談; "Collected discourse on Natural History"). The journal was created around Makino, who handprinted each copy to distribute to the readership.[40] Later, some time during his 20s (1880s) while still in his home province, he began circulating a handmade periodical called Kakuchi zasshi (格致雑誌).This was also hand-copied by Makino with inkbrush on washi paper.[39][41]

At age 19, Makino mounted on a trip to Tokyo to see the 2nd National Industrial Exhibitions (1 March–30 June 1881). Accompanied by the senior manager (bantō)'s son and accountant clerks, Makino purchased books and a microscope.[42][32] Makino also visited the Natural History Bureau at the Ministry of Education where he was warmly received by naturalist Yoshio Tanaka and botanist Motoyoshi Ono (Ranzan's great-grandson) from whom he heard talk on the latest news in botany, and was shown around the facility's botanical garden.[43][44]

In 1881, Tomitarō married his fiancée and cousin Yamamoto Nao (山本猶) 2 years his junior in his hometown, and she became the new young madam of the Kishiya brewerie establishment.[45][46] Since he had a grand wedding in his hometown, Sakawa's local history makes clear record of it, but Makino himself did not mention this marriage in any of his writings, including his autobiography (Jijoden).[47]

Remove ads

Career

Summarize

Perspective

In July 1884 at age 22, he moved to Tokyo to pursue his botanical studies in earnest. At the University of Tokyo's Faculty of Science in the Botanical Institute (Shokubutsugaku kyōshitsu) he met Cornell-educated professor Ryōkichi Yatabe,[36][48] who granted the privilege to come freely to the Institute and make use of its library, equipment and other resources, allowing Makino to delve into his botanical research.[49] Makino started to send specimens to Karl Maximovich of Russia considered the foremost authority on East Asian flora at the time, and since these tended to be rare and curious samples, it delighted the Russian[50] to the extent that whenever Maximovich sent a copy of his work to the institute, he would send a separate copy privately for Makino.[50]

In 1887 at age 25, he co-founded the journal Shokubutsugaku zasshi (植物学雑誌; "Botanical Magazine") in collaboration with the institute's colleagues Ōkubo Saburo, Nobujirō Tanaka, Tokugorō Someya (染谷徳五郎) and others.[51], with contributions from Komajirō Sawada (澤田駒次郎), Mitsutarō Shirai, Manabu Miyoshi,[51] and Yatabe as well.[52] This same year Makino lost his step-grandmother (aged 77) who raised him.[36]

November 1888 at age 26, he began publishing the series Nippon shokubutsu shi zuhen (日本植物志図篇; "Illustrated Japanese Plants") which he had long been conceptualizing, at his own-expense.[53][54][55] Towards that end, he apprenticed himself at a printing press[f] in order to learn the techniques of lithography,[56] and he eventually drew the plant illustrations himself, considered "photo-like in accuracy",[52] and highly praised by Maximowicz.[57] It was arguably the first illustrated compendium (zukan) of flora published in Japan.[59][61] To Makino it was a "crystallization of his hardships" which he considered "presentable with pride to the world",[62] and a monument to Japanese biological history according to his biographer.[63]

Around this time, while Tomitarō was building his position as botanical researcher, the funding was backed by his home business, and after the grandmother's death, his cousin/wife Nao sent funds as requested to the point that Kishiya's business operation was in peril.[32] And despite already having a wife, Nao, in his home town, he fell in love at first sight with 14-year old Sue Ozawa (小澤壽衛) who was the popular seller-girl daughter of a confection store in Tokyo, and the couple began cohabiting in Negishi, Taitō-ku (formerly in Shitaya-ku), at a detached wing of a princely priest's villa, belonging to a prince assigned to Rinnō-ji in Nikkō. The following year their first daughter Sonoko (1888–1893).[64]

In 1889 he discovered a new species of plant, the yamatoguasa (ヤマトグサ) Theligonum japonica, published in a paper co-signed by Saburō Okubo that appeared in their Shokubutsugaku zasshi ("Botanical Magazine"). It was the first time in Japan that a scientific name was given to a plant species. [65][67][g] In 1890, he was collecting plants in the former Koiwamachi, Minamikatsushika District, Tokyo, when in an waterway he found an unfamiliar insect-eating aquatic plant. He had discovered the occurrence in Japan of Aldrovanda vesiculosa (Japanese: mujinamo) which was then only known to grow sporadically in various faraway parts of the world. The report he made about this gained him world-wide notice in botanical circles.[69][non-primary source needed]。

In 1890, at age 28, he married Sue[ko] Ozawa (小澤壽衛子).[70] The same year he was banned from the Botanical Institute by Prof. Yatabe,[70][71] seemingly blocking his path to continue research. One of the reasons given for the expulsion was that the Institute had its own ideas about issuing anillustrated botanical compendium, and Makino's series posed a direct competition,[72] and Makino himself concluded that had been the case.[73] It has also been stated, in defense of Yatabe, that Makino made a regular habit of checking out books without permission, ultimately such a sanction became necessary.[72] Makino in despair even contemplated defecting to Russia and taking his collection of specimens to Maximowicz, hopefully to continue research abroad, but in 1891 his mentor died unexpectedly of influenza and the bold plan did not materialize.[74][75][h]

In 1891, his family business Kishiya was at a point of failing, and could no longer send funds to Makino. He returned to his home town to liquidate and divide family assets.[78] Tomitarō as the nominal tōshu (i.e, proprietor of the business, also meaning the head of the extended family) ruled to have Nao marry the senior manager (bantō) Kazunosuke Inoue (井上和之助)[i] Nao and her husband however soon folded the Kishiya business.[80][81][j]

During a period of stay in his province, one thing he did was to meddle in the local education of western music.[k] Then a telegram arrived telling him his young daughter had died, so he hastened back to Tokyo,[85]having accepted 600,000 yen from his family fortune.[citation needed]

In 1893, Prof. Yatabe was ousted from Tokyo University replaced by Jinzō Matsumura, who invited Makimura back to fill the post of assistant[86] on On 11 September.[87] On the assistant's flimsy salary of 15 yen per month, it grew difficult for him to support his growing family,[86][l] and not enough to sustain his spending habits on research, purchasing books, etc., yet he was determined to purchase all costly books he deemed necessary, going into deep debt.[88] He couldn't pay his rent, and one time his property got seized and auctioned off.[89]

In 1896, he was ordered to go on an expedition to Taiwan (which had been ceded to Japan after the war by the Treaty of Shimonoseki) to collect plants.[90][91] He reported a creeping fig used for making aiyu jelly as a new species (though it later was found to be a variety)[92] He continued to collect plants from various regions and conduct his research, preparing specimens and publishing literature. But his lack of formal education, as well as his old habit of borrowing university-owned books without clearance and not returning them in timely fashion, constantly caused resentment and tension from some colleagues.[32]

In 1900, Makino's financial straits were noticed by Tokyo University president Arata Hamao who appointed Makino to head the editing of the Dai-Nippon shokubutsu shi ("Greater Japan Botanical Journal") due out from the university,[m] so that a separate compensation package could be rewarded to Makino for the assignment.[86][93][94] However Matsumura did not approve (of) this special compensation[clarify][95] With such interference by Prof. Matsumura as far as Makino was concerned, Makino felt he had no choice but to give up on the continued publication of Dai-Nippon shokubutsu shi after the 4th volume.[96][94] The Institute as a whole regarded this publication cooling, and it seemed to Makino as if they were wishing the journal to fail, and such compounded reasons led to the discontinuation.[97][95] A salary discrimination issue has been brought up by a later biographer: while Makino received a starting salary of 15 yen as assistant in 1893, Matsumura had received 50 yen per month [99] as associate professor at age 28, ten years before.[100] On the other hand, Matsumoto's biographer opined that Matsumoto's criticism of Makino was "Fleeting", and if Makino took it as bullying, that was a character flaw on his part.[101]

Makino eventually fell from Prof. Matsumura's favor, just as he fell from Prof. Yatabe's grace earlier.[102] Pressures from Matsumura and others had ben countervailed by Kakichi Mitsukuri (Dean of the College of Science, Tokyo Imperial University 1901–1907)[n] who took Makimura under his aegis, but when a new dean Jōji Sakurai who was not well-versed in the affairs of the Botany Section, followed by the death of Mitsukuri succumbing to illness in 1909, the allegedly elated Prof. Matsumura took the opportunity to suggest Makimura's removal to the new dean. However, Makimura's firing did not come to pass.[103]

Instead, Dean Sakurai negotiated directly with Makimura and as of 30 January 1912 (Makimura at age 49), promoted him to lecturer with an increased salary to 30 yen.[104] Makino would remain as lecturer of the College (which in 1919 became (later to the Faculty of Science, Imperial University of Tokyo[105] and "Imperial" removed in the postwar)) until tendering his resignation on 31 May 1939 at age 77.[106][107] So counting from him his assistantship in 1893, he was in the employ of Tokyo University for some 46 years.

In 1916, Makino's collection of 300,000 specimens were nominally sold to young philanthropist Takeshi Ikenaga]], and transferred to what would become the Ikenaga Botanical Research Institute in Egeyama, Kobe.[108][111] Word had gotten out that Makino was planning to sell off his collection, whereby agronomist Chūgo Watanabe (渡辺忠吾) wrote a column warning that it would be the shame of the nation if the collection were allowed to leave the country. Two Kobe philanthropists stepped up to help, namely Fusanosuke Kuhara and Takeshi Ikenaga who was a 25 year-old student at the time but had his father's inheritance at his disposal. Ikenaga purchased the lot for 30,000 yen with intent to donate it back to Makino, but Makino who was overcome by emotion insisted it be kept, so the 300,000 specimens came to be housed in Ikenaga's research facility. Ikenaga continued to support financial for some years afterwards.[112][113]

1916 was also the year Makino founded the Shokubutus kenkyū zasshi aka Journal of Japanese Botany which he bore the expenses himself until the 3rd issue.[114][115] The publication was intermittent, The journal thus remained on a rocky course.[116][o] The journal floundered when the supporter Haruji Nakamura died,[118] but the magazine was revived in 1926 with the financial aid of Jūsha Tsumura,[119] and later published by his company, Tsumura & Co. pharmaceutical.[117] Makino would also lose the patronage he had gained from Ikenaga as well,[120][121] ca. 1930.[122][p]

In April 1927, he received a doctorate of science by the endorsement of botanists Kenjirō Fujii and Seiichirō Ikeno.[124][125] The dissertation was written in English.[126]

Also in 1927 he gave name to a new variety of dwarf bamboo Sasaella ramosa var. suwekoana after his wife Sue[ko].[127][128][129] She died of an unspecified illness the following year,[130] though it is thought to have been uterine cancer.[131] She was 55-years old.[128][132]

When Makino learned that the German naturalist Siebold had named a variety of hydrangea (H. macrophylla Sieb. var. otaksa) after his local wife Kusumoto Taki,[q] Makino quite severely criticized the naming,[134] characterizing Taki who was a courtesan, with abusive insults,[135] and claiming it was a disservice to the "lovely and guileless" flower whose "sanctity.. had been defiled".[127][r]

He published the 7-volume Shokubutsugaku zenshū (植物学全集; "Complete botanical collection", 1934–1936) which also garnered him the Asahi Prize in 1937, and the newspaper dubbed him "the father of Japanese plants".[136][137][138]

In 1939 he quit his post as lecturer at the University of Tokyo.[106][107]。

In 1940 he published what may be called his magnum opus, Makino's Illustrated Flora of Japan (Makino Nihon Shokubutsu Zukan),[139][140][142] which is still used as an encyclopedic text today.

In 1945, he evacuated away from WWII air raids to Hosakamura village, Kitakoma District, Yamanashi (present-day Nirasaki).[143][144]

On 7 October 1948, he was invited to give lecture to Emperor Hirohito, which was conducted in a Q&A basis while walking in the Imperial Palace, Tokyo#Fukiage Garden.[145] In 1949, he suffered a bout of catarrh and became critically ill but recovered.[146][144] In 1950, he was elected fellow of The Japan Academy.[147][148] And on 14 November, all the new fellows were invited by the Emperor for lunch, with opportunity to present summaries of their research.[149]

In 1951, a team was organized to try to organized the approximately 500,000 specimens accumulated in unsorted piles at Makino's home. The team was spearheaded by lichenologist/pharmacologist Yasuhiko Asahina who headed Kaken, and called itself the Doctor Makino specimen preservation committee (牧野博士標本保存委員会).[150][151] The Ministry of Education awarded a 300,000 yen subsidy the task of organizing the specimens into order began the following year.[152]

Makino was among the 1st recipients of the honor of Person of Cultural Merit in 1951.[150][153] And in October 1953, at age 91, he was chosen to be the first Honorary Citizen of Tokyo.[10]

His health failed him from 1954 onwards, and he tended to be bedridden.[154]

In 1956, he published Shokubutsugaku 90 nen (植物学九十年) (September) and Makino Tomitarō jijoden (牧野富太郎自叙伝) (December).[155][s] 17 December that year, he was made honorary citizen of his hometown, Sakawa.[155]

Decisions had been made in 1956 to build the Makino Herbarium in Tokyo and the Makino Botanical Garden in Kōchi Prefecture,[156] before Makino's death in 1957 at age 94. He was posthumously given court rank of Junior Third Rank, and decorated with The Order of the Rising Sun with the Double Rays[t] and the Order of Culture.[157] He is buried at Tennō-ji temple, but a portion of his remains are interred in Sakawa also.[158]

Makino Botanical Garden in Godaisan, Kōchi opened in April 1958.[159][160] And on 18 June, 1958, The Makino Herbarium opened at the Tokyo Metropolitan University whose collection was built upon the 400,000 specimens bequeathed by the family.[161][65]

In 2008 Makino also became honorary citizen of Nerima-ku[162]

Remove ads

Selected works

In a statistical overview derived from writings by and about Makino, OCLC/WorldCat includes roughly 270+ works in 430+ publications in 4 languages and 1,060+ library holdings.[163]

- Makino shokubutsugaku zenshū (Makino's Book of Botany) Sōsakuin, 1936

- Makino shin Nihon shokubutsu zukan (Makino's New Illustrated Flora of Japan), Hokuryūkan, 1989, ISBN 4-8326-0010-9

Remove ads

See also

- Ranman (TV series): the main character Mantarō Makino (played by actor Ryunosuke Kamiki) is inspired by Makino, and its story is based on his real life.[165]

Explanatory notes

- Makino later became consultant to the Zaidan hōjin Itagaki-kai (est. 1945 by merger).[33] Itagaki Taisuke from Tosa was the preeminent leader of the movement.

- Yatabe around 1886–1887 also had quarrel with another junior botanist, the aforementioned Tokutarō Itō, over the discovery and naming of togakushisō, banning him from the Institute.[76] Itō had reported in a botanical journal first, but as Podophyllum japonicum. Afterwards Yatabe sent to his own sample of the plant (which he said were collected in 1884), and received opinion from Maximowicz that this was a new genus wnaming the plant Yatabe japonicum in private communication. But Itō asserted the discoverer's first naming rights, and republished the plant as Ranzania japonica T. Ito, incurring Yatabe's wrath.[77][76]

- The son of the bantō who accompanied Tomitaro to Tokyo in 1881 was Kumakichi, son of Takezō Saeda (佐枝竹蔵). The bantō had since been replaced and was not succeeded by Kumakichi Saeda. But in the TV drama Ranman, the fictionalized Takeo Inoue was a composite, being both the one to tag along with Makino to Tokyo, and the one to marry his "sister" and take over the business.[79]

- A vicious rumor spread causing the couple to flee Sakawa, but their headstones were discovered in the burial ground on the mountains in recent years.[82]

- He declared the western music instruction misguided and the music teacher unfit. To prove his point, he organized a recital and even acted as conductor to enlighten the locals as to what true western music sounded like. [83] Even in his past as elementary school instructor, he was concern about music education and had donated an organ out of his own pocket.[84]

- Also grandson of Mitsukuri Genpo.

- "[Makino] edited the Journal through vol. 8 in 1933. Subsequently, the Journal has been edited by The Editorial Board of The Journal of Japanese Botany from vol. 9 no. 1 in May 1933 to the present issue. The Editorial Board has been represented by Yasuhiko Asahina (1933–1975), Hiroshi Hara (1975–1987), Shoji Shibata (1987-2006), and Hiroyoshi Ohashi (2006–present) as the Editor-in-Chief".[117]

- While biographer Shibuya comments that the Ikenaga Botanical Research Institute was far less magnanimous in relation to Makino's far too great expectations,[123] a more recent biographer (Ueyama) writes that Tominaga had misappropriated a portion of the largesse and squandered it in the brothels of Fukuhara, Kobe, as Ikenaga was based in Kobe, and this was the reason he got cut off financially, alongside other misbehaviors.[47]

- Taki and Siebold had a daughter between them, Kusumoto Ine), who became a physician.

- Though this "defilement" by a "prostitute" point might be in jest, as the remark concludes Oh my poor hydrangea (アア可哀そうな我があじさゐよ),[127] and perhaps only incidental as it follows a serious botanical point to be made, which was that Makino suspects the flower which Siebold named H. azisai was not what the Japanese people called ajisai but rather the gakuajisai.[127]

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads