Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Materialism controversy

Philosophic and scientific debate held in 19th-century Germany From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The materialism controversy (German: Materialismusstreit) was a public debate in the mid-19th century about how new developments in the natural sciences might affect existing worldviews. During the 1840s, a new form of materialism emerged, shaped by advances in biology and the decline of idealistic philosophy. This form of materialism sought to explain human beings and their behavior through scientific methods. The central question of the debate was whether scientific discoveries were compatible with traditional ideas such as the existence of an immaterial soul, a personal God, and human free will. The discussion also touched on deeper philosophical issues, such as what kind of knowledge a materialist or mechanical view of the world could offer.[1]

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In his Physiologische Briefe from 1846, zoologist Carl Vogt argued that mental processes were entirely physical, famously stating that "thoughts stand in the same relation to the brain as bile does to the liver or urine to the kidneys."[2] In 1854, the physiologist Rudolf Wagner criticized this view in a speech to the Göttingen Naturalists' Assembly. He argued that religious belief and science belonged to separate areas of understanding, and that natural science could not answer questions about God, the soul, or free will.

Wagner’s comments were strongly worded, accusing materialists of trying to undermine spiritual values. His attacks sparked sharp responses from Vogt and others. The materialist position was later defended by figures such as physiologist Jakob Moleschott and physician Ludwig Büchner, brother of writer Georg Büchner. Supporters of materialism saw themselves as opposing what they viewed as outdated philosophical, religious, and political ideas. While their approaches varied, they found growing support among the middle classes.[3] The idea of a scientific worldview became an important feature in the broader cultural debates of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Remove ads

Development of natural scientific materialism

Summarize

Perspective

Emancipation of biology

The rise of popular materialism in the mid-19th century was partly driven by growing criticism of romantic and idealist natural philosophy.[4] This critique became widespread after 1830 and influenced science, philosophy, and politics alike.

One major scientific development that supported this shift was the emergence of cell theory, founded by botanist Matthias Jacob Schleiden. In 1838, Schleiden published a study on plant development in which he identified the cell as the basic unit of all plant life and emphasized the role of the cell nucleus, discovered in 1831, in plant growth.[5] This theory marked a turning point in botany, which had previously focused mainly on describing the external forms of plants. Schleiden combined his scientific findings with a strong critique of idealist natural philosophy. He argued that scientific knowledge must be based on direct observation, unlike the speculative systems of earlier philosophers. According to him, abstract theorizing not grounded in evidence had to be rejected.[6]

Schleiden’s call for a more scientific and observation-based approach soon influenced other areas of biology. In 1839, Theodor Schwann published Microscopic Investigations on the Similarity in Structure and Growth of Animals and Plants, extending Schleiden’s ideas to animals. Schwann proposed that all living things are made of cells and that tissues and organs develop through cell growth and reproduction. Building on this, physician Rudolf Virchow later summarized the idea by stating: “Life is essentially cellular activity".[7] These insights laid the foundation for a scientific understanding of life, which materialist thinkers would build upon in the following years.

Turning away from idealistic philosophy

At the same time, a broader critique of German idealism began to take shape, especially in the years before the 1848 revolutions (the Vormärz period).[8] While many scientists still opposed materialism, criticism of idealist philosophy became more common, particularly among younger intellectuals.

One of the most influential figures in this movement was Ludwig Feuerbach, whose 1841 work The Essence of Christianity had a major impact.[9] Feuerbach had studied under Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in Berlin and initially followed the idealist tradition. However, by the late 1830s, he began to reject it. Like other young Hegelians, he grew dissatisfied with idealism's abstract systems and its alignment with conservative politics. In 1839, Feuerbach openly criticized Hegel's philosophy. While he acknowledged its internal logic, he argued it was too far removed from the natural world and human experience. Feuerbach believed that philosophy should be grounded in the senses and in the physical reality of nature and humanity. As he put it: “All speculation that seeks to go beyond nature and man is vain.[10] Although Feuerbach was not a scientist, his ideas about grounding knowledge in human experience and nature echoed the goals of the new biology. He promoted a type of anthropology—a theory of humanity based on lived experience—rather than a speculative or purely scientific approach.

Feuerbach’s most controversial ideas came from his critique of religion. He argued that religion was not a reflection of divine truth, but a projection of human hopes and needs. God, he claimed, was not an external being, but a creation of the human mind. While he did not reject religion entirely, he believed its value lay in its psychological and emotional function, not in metaphysical truth. Religious doctrines, he argued, could not be proven through reason or science—they were, in his view, products of imagination rather than reality.

Remove ads

Carl Vogt and the political opposition

Summarize

Perspective

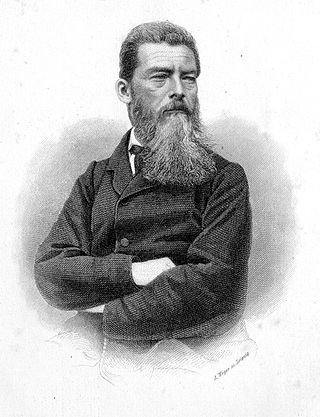

The materialism controversy was sparked in part by the writings of physiologist Carl Vogt, beginning in 1847. His commitment to materialism was shaped by the scientific and political reform movements of the time, as well as his own personal and political development.[11] Vogt was born in Giessen in 1817, into a family with both scientific and revolutionary traditions. His father, Philipp Friedrich Wilhelm Vogt, was a professor of medicine who moved to Bern in 1834 after facing political persecution. On his mother’s side, political activism was also a strong influence: Louise Follen’s three brothers—Adolf, Karl, and Paul Follen—were all involved in nationalist and democratic causes and eventually went into exile.[12]

In 1817 Adolf Follen drafted a proposal for a future German constitution and was later arrested for his political activities. He avoided a 10-year prison sentence by fleeing to Switzerland. Karl Follen was suspected of encouraging the assassination of conservative writer August von Kotzebue and escaped to the United States, where he became a professor at Harvard University. The youngest brother, Paul Follen, helped found the Gießener Auswanderungsgesellschaft in 1833, which aimed to establish a German republic in the U.S. Though the plan failed, Paul settled in Missouri as a farmer.

Carl Vogt began studying medicine at the University of Giessen in 1833, but soon switched to chemistry under the influence of Justus Liebig, a pioneer of organic chemistry. Liebig’s experimental approach, which rejected the traditional divide between living and non-living matter, helped lay the groundwork for Vogt’s later materialist views.[13] In 1835, however, Vogt had to leave Giessen after helping a politically persecuted student escape. He fled to Switzerland and completed his medical degree in 1839.

In the early 1840s, Vogt became active in both scientific and political reform circles, though he had not yet fully adopted a materialist worldview. His ideological shift took place during a three-year stay in Paris, where he came into contact with anarchist thinkers like Mikhail Bakunin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. These interactions significantly influenced his political ideas. Starting in 1845, Vogt published the Physiological Letters (Physiologische Briefe), which aimed to make physiology more accessible to the public. Inspired by Liebig’s Chemical Letters, the early volumes were written in clear, popular language. While the first letters avoided strong ideological claims, the 1846 letter on the nervous system marked a turning point. In it, Vogt argued that consciousness, will, and thought originate solely in the brain, a direct challenge to spiritual or dualist explanations of the mind.[14]

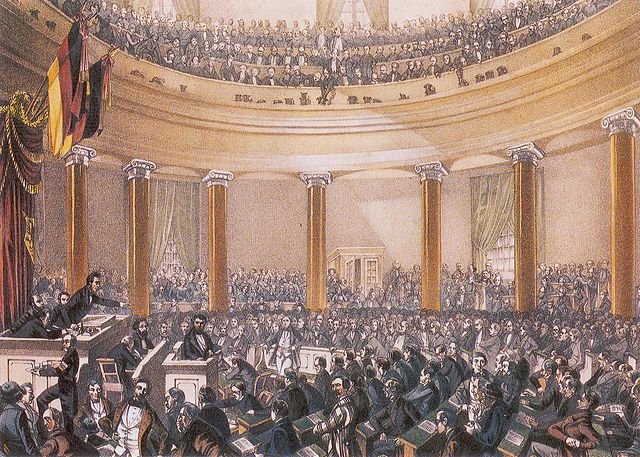

At this stage, however, Vogt prioritized political activism over theory. In 1847, he was appointed professor of zoology in Giessen with the help of Liebig and Alexander von Humboldt. But shortly afterward, the Revolutions of 1848 broke out across Europe. When the uprising reached Giessen, Vogt led the local militia and was elected to represent Hesse-Darmstadt in the Frankfurt Parliament (1848–1849), a democratic assembly aiming to unify Germany. After the Prussian King Frederick William IV refused the crown offered by the parliament and conservative forces regained control, Vogt joined the remaining 158 deputies in Stuttgart to form the so-called rump parliament. This assembly was short-lived, and on 18 June 1849, troops from Württemberg forcibly shut it down. Vogt fled once again to Switzerland and took refuge at his family home.

With his political career in ruins and his academic post lost, Vogt returned to scientific work. His research from this point onward took on a more openly ideological tone, as he began to interpret biological processes through the lens of materialist philosophy.

Remove ads

Progression of the debate

Summarize

Perspective

Materialism controversy until 1854

In 1850, Vogt travelled to Nice to continue his zoological research, as his academic prospects in Germany remained uncertain. A year later, he published a book on animal societies, which combined zoological observations with a sharp political critique of the German state.[15] In the book, Vogt argued in favor of anarchism, claiming that all forms of government and law were signs that humanity had not yet returned to its natural state. Vogt’s argument for anarchism was rooted in his biological and materialist worldview. He believed that humans, like animals, are entirely material beings and part of the natural world. Therefore, biology not only supported materialism but also challenged existing social and political structures.

Despite—or because of—its controversial content, the book attracted public attention in Germany. In 1852, Vogt published Bilder aus dem Thierleben (Images from Animal Life), which further developed his materialist views and strongly criticized German academic circles. He argued that any biologist who thinks clearly must recognize the truth of materialism, especially given the evidence from animal experiments.[16] From this, he concluded that if mental functions depend on brain functions, then the soul cannot exist independently of the body or survive after death. Furthermore, if the brain operates according to natural laws, then so must the soul—leaving no room for free will:

Thus the door would be opened to simple materialism – man, as well as the animal, would be only a machine, his thinking the result of a certain organisation – free will therefore abolished? ... Truly, that is so. It really is so.[17]

Vogt argued that those who rejected these conclusions misunderstood the implications of physiological science. His criticism was partly aimed at Rudolf Wagner, an anatomist and physiologist from Göttingen, who had attacked Vogt in an 1851 article in the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung. Wagner accused Vogt of replacing God with “blind, unconscious necessity".[18] Wagner also proposed that a child’s soul was composed of equal parts from the mother’s and father’s souls. Vogt responded sarcastically, pointing out that such an idea contradicted the theological principle of the soul’s indivisibility and was scientifically implausible. Instead, he argued, character traits—like physical features—are inherited from parents through the brain, and therefore the idea of a "composite soul" could be explained in purely materialist terms.[19]

Göttingen Naturalists' Meeting

During the summer of 1854, the 31st Naturalists' Meeting was held in Göttingen. A major topic of discussion was the existence of the soul and its compatibility with emerging materialist views in science.[20] During the event, physiologist Rudolf Wagner gave a prominent lecture on human creation and the nature of the soul, in which he sharply criticized materialism. He argued that denying the existence of a soul created by God—and especially the rejection of free will—would undermine the moral foundations of society.[21]

Wagner claimed that materialist theories, such as those proposed by Carl Vogt, reduced human beings to passive machines without responsibility, which conflicted with the ethical duties of scientists. Later that year, Wagner published a second paper that expanded on his criticisms. He argued that science and faith occupy separate domains, and that science alone could neither prove nor disprove religious beliefs.

He explained that while physiologists can describe the structure and function of physical organs, their findings can be interpreted in different ways. Materialists use these observations to argue that mental functions are based on physical processes, while dualists believe the body interacts with an immaterial soul. Wagner maintained that physiology cannot determine which interpretation is correct. He stated: "There is not a single point in the biblical]doctrine of the soul ... that would contradict any doctrine of modern physiology and natural science."[22]

Charcoal burning faith and science

Wagner’s public criticism brought the materialism debate into the spotlight. In response, Carl Vogt published a strongly worded counterattack titled Köhlerglaube und Wissenschaft (Charcoal-Burner's Faith and Science), directly aimed at Hofrat Rudolf Wagner. The first part of the text consisted largely of personal attacks. Vogt accused Wagner of lacking scientific originality, claiming that he relied on the work of others while presenting himself as a leading scholar. He also alleged that Wagner had tried to silence materialist thinkers by using political influence and state power. Wagner had linked the denial of free will with the revolutionary upheavals of 1848, suggesting that materialist ideas posed a risk to political and social stability. Vogt, angered by this accusation, turned the discussion into a broader attack on Wagner’s attempt to reconcile religion and science.[23]

In the second part of the pamphlet, Vogt took aim at Wagner’s claim that simple religious belief—referred to sarcastically as Köhlerglaube (the "faith of a charcoal burner")—could coexist with modern science. Vogt argued that if someone places the soul beyond the reach of scientific investigation, that belief cannot be tested or disproven. However, he insisted that such an assumption was scientifically meaningless. Vogt argued that the growing understanding of how mental functions depend on the brain supported a materialist interpretation. He pointed out that Wagner himself accepted that all organs, such as the kidneys or muscles, follow biological laws. Yet when it came to the brain, Wagner made an exception by invoking an immaterial soul. According to Vogt, this selective reasoning showed that belief in an immaterial soul was a holdover from theology, not a conclusion supported by science. He concluded that materialism offered a more consistent and evidence-based framework for understanding human nature.[24]

Food, strength and substance

By 1855, materialism had become an increasingly influential intellectual movement, even though the ideas promoted by Carl Vogt continued to face resistance in academic and political circles. Vogt was supported by two younger scientists, Jakob Moleschott and Ludwig Büchner, who also advanced materialist ideas through widely read popular science publications. Together, the three were seen as prominent advocates of materialism, which many at the time considered a compelling and coherent worldview. The controversy surrounding materialism sparked wider public debates about the relationship between science and society. These discussions also played a key role in the popularisation of science, paving the way for the reception of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in the late 1850s.[25]

Jakob Moleschott was born in 's-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands, in 1822. He encountered Hegelian philosophy early in his life but went on to study medicine at the University of Heidelberg.[26] Influenced by Ludwig Feuerbach, Moleschott developed a materialist perspective focused on metabolism and nutrition. In his book Die Lehre der Nahrungsmittel: Für das Volk (The Science of Food: For the People), Moleschott argued that nutrition was the foundation of both physical and mental functions. This reflected his belief that humans are entirely material beings. His aim was not only to deny the existence of an immaterial soul or God, but also to use scientific knowledge to improve people's lives, especially the poor, by offering practical dietary advice.

In 1850, Moleschott sent a copy of the book to Feuerbach, who responded with a widely read review titled Die Naturwissenschaft und die Revolution (Science and the Revolution). While Feuerbach had previously positioned his philosophy beyond both idealism and materialism, this publication marked his explicit support for the materialist movement. He argued that while philosophers continued to debate the nature of body and soul, the natural sciences had already resolved the question in favor of materialism.[27]

Ludwig Büchner, born in Darmstadt in 1824, played an even more prominent public role than Moleschott. As a student, he met Carl Vogt, and in 1848 joined Vogt’s citizen militia during the revolutionary uprisings. After an unsatisfying academic career—including a brief assistantship at the University of Tübingen—Büchner decided to publish a concise and accessible overview of the materialist worldview. His book, Kraft und Stoff (Force and Matter), became a major success: it went through 12 editions in 17 years and was translated into 16 languages. Unlike Vogt and Moleschott, who framed their materialism through their own scientific research, Büchner presented it as a general scientific summary, written for readers without a background in philosophy or science. The central idea was the unity of force and matter—a concept Moleschott had also emphasized. Büchner argued that forces cannot exist without matter, and matter cannot exist without forces. Therefore, the idea of an immaterial soul was inconsistent with scientific understanding, since it would require a force without a material base.

Remove ads

Reactions in the 19th century

Summarize

Perspective

Philosophy of neo-Kantianism

Materialism, as promoted by scientists like Carl Vogt, Jakob Moleschott, and Ludwig Büchner, was presented as a direct consequence of empirical scientific research. Following the decline of German idealism, many saw academic philosophy—especially as taught in universities—as disconnected from reality and reduced to speculative thought. Even philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, once aligned with idealist traditions, placed his trust in the natural sciences to answer longstanding philosophical questions such as the relationship between body and soul.

However, a strong philosophical critique of materialism did not emerge until the 1860s, with the rise of Neo-Kantianism. In 1865, Otto Liebmann published Kant und die Epigonen (Kant and His Followers), a work that sharply criticized major post-Kantian thinkers—from German idealists to Arthur Schopenhauer. Liebmann famously ended each chapter with the refrain: "So we must go back to Kant!".[28] The following year,Friedrich Albert Lange published Geschichte des Materialismus (History of Materialism), in which he aligned himself with the Neo-Kantian position. Lange accused the scientific materialists of “philosophical dilettantism”, claiming that they overlooked central insights of Kantian thought.[29]

At the core of Kant’s philosophy, particularly in the Critique of Pure Reason, is the question: What are the conditions for the possibility of knowledge? Kant argued that human beings do not perceive the world as it truly is, but rather through cognitive structures shaped by the mind. Concepts such as cause and effect, unity, and multiplicity are not features of the external world itself but mental categories we impose on our experiences. Similarly, space and time are not absolute properties of reality but forms of human perception. Since all experience is already filtered through these mental structures, Kant concluded that we can never know things-in-themselves—that is, reality as it exists independently of human perception. As a result, Kant held that it is impossible to scientifically prove or disprove the existence of free will, a personal God, or an immaterial soul. These ideas lie outside the scope of empirical investigation.

Friedrich Albert Lange used Kant’s theory to argue that materialism made a fundamental mistake: it claimed that only matter exists, but failed to recognize that even scientific descriptions of matter are shaped by human perception. Therefore, science cannot claim to describe absolute reality; it only describes how reality appears to us through our cognitive framework.[30] This argument was supported by physicist and physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz, who had studied the physiology of perception in the 1850s. In his 1855 lecture, Über das Sehen des Menschen (On Human Vision), Helmholtz explained that vision does not offer a faithful copy of the external world. Instead, visual perception is constructed by the brain based on incomplete sensory input. Helmholtz’s work echoed Kant’s view: every act of perception involves interpretation, and this interpretation is shaped by human cognitive faculties. Because of this, direct access to objective reality—the “thing-in-itself”—is not possible.[31]

Ignoramus et ignorabimus

The scientific materialists did not engage with the arguments of the Neo-Kantians, as they saw the reference to Kant as just another speculative attack on the results of the natural sciences. A more serious challenge came from Emil Heinrich Du Bois-Reymond, a prominent physiologist, whose 1872 lecture Über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens (On the Limits of Understanding Nature) posed a direct challenge to the foundations of materialist thought. In this lecture, Du Bois-Reymond famously declared that certain aspects of nature, particularly consciousness, would always remain beyond scientific explanation. He summed this up with the Latin phrase: "Ignoramus et ignorabimus" (Latin for "We do not know and we will never know"). This statement sparked the Ignorabimus controversy, a long-running public and scientific debate over whether science could ever fully explain the human mind and consciousness. The intensity of the debate rivalled—and in some circles exceeded—that of the earlier Vogt–Wagner controversy of the 1850s. However, by this point, materialists found themselves increasingly on the defensive.[32]

Du Bois-Reymond criticized the materialist position for failing to explain how consciousness arises from the physical processes of the brain. While Vogt, Moleschott, and Büchner pointed to the observable dependence of mental functions on brain activity—especially demonstrated through brain injuries and animal experiments—this, he argued, did not address the deeper issue. However, for Du Bois-Reymond, this approach was insufficient. He argued that demonstrating a correlation between brain activity and mental states does not explain why or how subjective experience—pain, desire, colors, sounds, and so on—emerges from physical processes.

Du Bois-Reymond concluded that there was no intelligible link between the objective facts of physics and the subjective nature of conscious experience. As such, consciousness represented a fundamental limit to what science could explain.[33]

The Ignorabimus speech revealed a major weakness in the materialist worldview. While the materialists insisted that consciousness was a product of the brain, they conceded that science could not yet—and might never—explain it. This gap contributed to a broader shift in the scientific worldview during the late 19th century, from strict materialism to monism. Ernst Haeckel, one of the most influential scientists of the time, became the leading advocate of this monistic worldview. Like the materialists, he rejected dualism, idealism, and the immortal soul, but he also moved away from the materialist claim that only matter was real.[34]

Unlike materialism, monism held that mind and matter were equally fundamental and inseparable aspects of a single underlying reality. In this way, spirit was no longer something that had to be explained in terms of matter alone, potentially resolving the issue raised by Du Bois-Reymond.

Even Ludwig Büchner, initially one of the most prominent advocates of materialism, eventually distanced himself from the term. In a letter to Haeckel dated 1875, he wrote:

I ... have therefore never used the term 'materialism', which evokes a completely one-sided idea, for my school of thought and only accepted it here and there later out of necessity because the general public knew no other word for the whole movement ... . The term 'monism' that you suggest is very good in itself, but it is very doubtful whether it will be accepted by the general public.[35]

Political and ideological impact

Although scientific materialism gained considerable popularity among the general public in 19th-century Germany, its proponents—Carl Vogt, Jakob Moleschott, and Ludwig Büchner—faced significant political opposition. All three lost their academic positions largely because of their outspoken advocacy of materialism. Vogt’s revolutionary materialism, in particular, failed to gain traction in the reactionary political climate following the revolutions of 1848. Scientific materialism also struggled to influence broader political movements, in part due to ideological conflicts with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marx disparaged Vogt as a “small-university beer bouncer and misguided Barrot of the Reich",[36] and personal denunciations escalated between the two camps. Marx’s circle even accused Vogt of espionage for France.[37]

The shifting political context was reflected in the work of Ernst Haeckel, who adopted the materialists’ scientific worldview but infused it with new political meaning. Seventeen years Vogt’s junior, Haeckel became a prominent advocate of Darwinism in Germany during the 1860s. His polemical rejection of “church-wisdom and ... after-philosophy",[38] echoed the earlier scientific materialists’ critiques. Where Vogt emphasized physiology as the foundation of a scientific worldview, Haeckel placed Darwin’s theory of evolution at the center. He famously framed the cultural conflict as:

In this spiritual battle, which now moves the whole of thinking humanity and which prepares a humane existence in the future, on the one side under the bright banner of science stand: freedom of thought and truth, reason and culture, development and progress; on the other side under the black banner of hierarchy: spiritual bondage and lies, irrationality and crudeness, superstition and regression.[39]

For Haeckel, the idea of “progress” was chiefly anti-clerical, targeting the church rather than the state. The Kulturkampf, initiated by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1871, gave Haeckel a political platform to align his anti-clerical monism with Prussian government efforts to curb ecclesiastical influence.

Remove ads

Reception in the 20th century

Summarize

Perspective

In the 19th century, scientific materialism played a significant role in ideological debates, especially through discussions surrounding Darwin's theory of evolution and Ernst Haeckel's monism, which gained prominence in the 1860s. Büchner’s Kraft und Stoff remained a bestseller, reflecting enduring popular interest. However, the question of a unified scientific worldview continued to provoke controversy.

The First World War and Haeckel’s death in 1919 marked critical turning points. In the subsequent Weimar Republic, the debates of the mid-19th century lost much of their relevance. Philosophical trends in the interwar period consistently criticized materialism despite differing viewpoints. This included the rise of logical positivism, which upheld the ideal of a scientific worldview but framed it in an anti-metaphysical way.[40] Logical positivists held that only empirically verifiable propositions were meaningful, thereby dismissing materialism, monism, idealism, and dualism as speculative and philosophically misguided. Materialist theories of consciousness were largely abandoned until their revival in Anglo-Saxon philosophy in the 1950s, by which time the 19th-century materialists—Vogt, Moleschott, and Büchner—had been largely forgotten. Post-war materialist philosophy instead focused on advances in contemporary neuroscience.[41]

Scientific materialism remained largely neglected in the histories of science and philosophy until the 1970s.[42] In the German Democratic Republic (GDR), Dieter Wittich was an early scholar to revisit the movement; his 1960 doctoral thesis examined the scientific materialists in detail.[43] Wittich later edited a 1971 collection of their writings, Vogt, Moleschott, Büchner: Schriften zum kleinbürgerlichen Materialismus in Deutschland, published by Akademie Verlag. In his introduction, Wittich praised the materialists’ political, scientific, and religious critiques but also highlighted their philosophical limitations, describing them as “petty-bourgeois materialists” who clung to metaphysical materialism even as dialectical materialism had become a prevailing reality.[44]

In 1977, Frederick Gregory, an American historian of science, published Scientific Materialism in Nineteenth Century Germany, now a standard reference. Gregory contended that the significance of Vogt, Moleschott, and Büchner lay less in their specific materialist doctrines than in their socially impactful critique of religion, philosophy, and politics. He characterized their hallmark not as materialism, but as a form of atheism grounded in a "humanistic religion."[45]

Modern scholarship generally recognizes the role of scientific materialism in the secularization processes of the 19th century, while its philosophical rigor remains debated. Renate Wahsner, for example, argues that it is untenable to deny these thinkers "sharpness and depth of thought".[46] it is untenable to deny these thinkers "sharpness and depth of thought." Conversely, Kurt Bayertz defends their enduring relevance, noting that Vogt, Moleschott, and Büchner developed “the first fully developed form of modern materialism” — a form that, though only one variant of materialism, remains the most influential and effective in modernity.[47] Thus, contemporary analyses of materialism’s philosophical controversies often trace their origins back to the 19th-century scientific materialists.

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads