Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

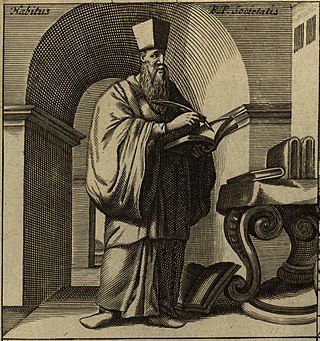

Michał Boym

Jesuit missionary, scientist, and explorer in China From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Michał Piotr Boym, SJ (Chinese: 卜彌格; pinyin: Bǔ Mígé; c. 1612 – 22 June 1659) was a Polish Jesuit missionary, scientist, and explorer active in China during the 17th century.[1][2]

He was among the first Westerners to travel extensively within the Chinese mainland and is credited with introducing European audiences to aspects of Chinese geography, medicine, and natural history. Boym authored several important works, including treatises on Asian flora and fauna, and a detailed account of the Ming–Qing transition.

The first known Chinese–European dictionary, published posthumously in 1670, is often attributed to Boym.

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Michał Boym was born in Lwów, Poland (now Lviv, Ukraine), around 1614, into a well-off family of Hungarian descent. His grandfather, Jerzy Boim, came to Poland from Hungary with King Stephen Báthory and married Jadwiga Niżniowska.[3][1] Michał’s father, Paweł Jerzy Boim (1581–1641),[3] served as a physician to King Sigismund III of Poland.[1][2] Of Paweł’s six sons, the eldest, Jerzy, was disinherited; Mikołaj and Jan became merchants; Paweł became a doctor; and Michał and Benedykt Paweł joined the Society of Jesus.[3] The family commissioned the Chapel of the Boim family in Lviv’s central square, built around the time of Michał’s birth.[3]

In 1631, Boym joined the Jesuits in Kraków[1] and was ordained a priest. After nearly a decade of studies in the monasteries of Kraków, Kalisz, Jarosław, and Sandomierz, Boym embarked on a voyage to East Asia in 1643. He first travelled to Rome, where he obtained a blessing from Pope Urban VIII, and then proceeded to Lisbon. Later that year, he joined a group of nine other priests and clerics on a voyage to Portuguese Goa, and later to Macau. There he initially taught at St. Paul Jesuit College (Macau), before moving to the island of Hainan, where he established a small Catholic mission. When the island was conquered by the Manchus, Boym fled to Tonkin (modern-day northern Vietnam) in 1647.

While Jesuits in northern and central China shifted their allegiance to the newly established Qing dynasty, Jesuits in the south continued supporting the Southern Ming loyalist regimes. In 1649, Boym was sent by the Canton-based Vice-Provincial of the China Mission, Álvaro Semedo, on a diplomatic mission to the court of the Yongli Emperor, the last ruler of the Ming dynasty, who still controlled parts of Southwestern China.[1]

At the Yongli court, Jesuit missionary Andreas Wolfgang Koffler (present there since 1645) had converted several members of the imperial family to Christianity, hoping this would draw support from Western monarchs. Among those converted were Empress dowager Helena Wang (Wang Liena), Maria Ma (Ma Maliya), the emperor’s mother, Anne Wang, and the heir to the throne, Prince Constantine (Dangding), Zhu Cuxuan.[1][4] The emperor’s eunuch secretary Pang Tianshou (龐天壽), known by his Christian name Achilles, was also a convert.[1][5]

Boym was chosen to deliver letters from Empress Dowager Helena and Pang Achilles to Pope Innocent X, the Superior General of the Jesuit Order,[6] and Cardinal John de Lugo. Additional letters were sent to the Doge of Venice and the King of Portugal. Accompanied by a young court official, Andreas Chin (Chinese: 鄭安德肋; pinyin: Zhèng Āndélèi),[7][8] Boym embarked on his return voyage to Europe.

After arriving in Goa in May 1651, Boym learned that the Portuguese crown had withdrawn support for the Ming cause, and the Jesuits now discouraged involvement in Chinese political affairs. Placed under house arrest, Boym eventually escaped and continued his journey on foot through Hyderabad, Surat, Bandar Abbas, and Shiraz, reaching Isfahan in Persia. He then travelled via Erzurum, Trabzon, and İzmir, arriving in Venice in December 1652 disguised as a Chinese mandarin to avoid political entanglements.

Initially refused an audience by the Doge of Venice, Boym secured support from the French ambassador and delivered his letters. However, the Pope—then hostile to French influence—reacted negatively, and the Jesuit Superior General Goswin Nickel also feared Boym’s mission could endanger Jesuit activities in Asia. Only in December 1655 did Pope Alexander VII receive Boym, offering sympathy but no material aid. The papal letter, however, opened diplomatic doors, and in Lisbon Boym gained an audience with King John IV of Portugal, who promised assistance.

In March 1656, Boym set out again for China. Of the eight priests accompanying him, only four survived the journey. Upon reaching Goa, he found the Portuguese authorities unwilling to allow him passage to Macau for fear of jeopardizing relations with the Qing. Determined, Boym travelled overland to Ayutthaya, capital of Siam, and from there by ship to northern Vietnam. In Hanoi, he sought guides to Yunnan, but failed to find any. Continuing the journey with only his companion Chang, Boym reached Guangxi, China, where he died on 22 June 1659, before he could deliver the Pope’s letter to the Yongli court. His burial place remains unknown.

Remove ads

Works

Summarize

Perspective

Boym is best remembered for his works describing the flora, fauna, history, traditions, and customs of the regions he travelled through. During his first journey to China, he wrote a short treatise on the plants and animals of Mozambique. The manuscript was sent to Rome but was never printed. During his return journey, Boym prepared a large collection of maps depicting mainland China and Southeast Asia. He planned to expand the work into nine chapters covering China’s geography, customs, political system, science, and inventions.

The significance of Boym’s maps lies in their accuracy: they were the first European maps to depict Korea correctly as a peninsula rather than an island. They also accurately located numerous Chinese cities that had previously been unknown to Europeans or known only from the semi-legendary accounts of Marco Polo. Boym also included representations of the Great Wall and the Gobi Desert. Although the collection was not published during his lifetime,[9] it substantially expanded European knowledge of China.

Boym’s best-known work is the Flora Sinensis (“Chinese Flora”), published in Vienna in 1656. The book was the first European publication to describe an ecosystem of the Far East. Boym emphasized the medicinal properties of Chinese plants and included appeals for support of the Catholic Chinese emperor. The volume also contained a poem of nearly one hundred chronograms, referencing the year 1655—the coronation date of Emperor Leopold I as King of Hungary—in an effort to gain the monarch’s patronage for Boym’s mission.

Athanasius Kircher later drew extensively on Flora Sinensis for the chapters on Chinese plants and animals in his China Illustrata (1667).[10] Boym also authored the first published Chinese dictionary for a European language—a Chinese–French dictionary included in the first French edition of Kircher’s work (1670).[11]

In other works—such as Specimen medicinae Sinicae (“Chinese Medicinal Plants”) and Clavis medica ad Chinarum doctrinam de pulsibus (“Key to the Medical Doctrine of the Chinese on the Pulse”)—Boym described aspects of traditional Chinese medicine and introduced diagnostic methods previously unknown in Europe, particularly the measurement of the pulse.[12][13][14] However, the authorship of Clavis medica ad Chinarum doctrinam de pulsibus has been disputed, and it is likely that it was actually written by the Dutch physician and scholar Willem ten Rhijne.[15]

Remove ads

See also

Notes and references

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads