Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Micheal Ray Richardson

American basketball player and coach (1955–2025) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

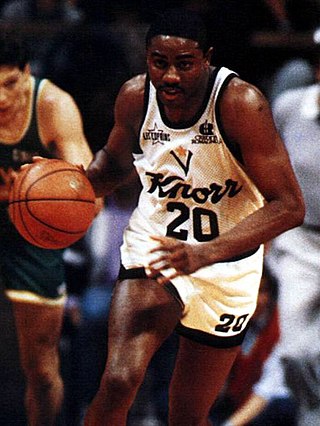

Michael Ray Richardson (April 11, 1955 – November 11, 2025), first name more commonly spelled Micheal[a] and known by the nickname "Sugar", was an American professional basketball player and head coach. He played college basketball for the Montana Grizzlies. The fourth overall pick in the 1978 NBA draft, Richardson played in the National Basketball Association (NBA) for eight years with the New York Knicks, Golden State Warriors, and New Jersey Nets. He was a four-time NBA All-Star and two-time NBA All-Defensive First Team selection who led the league in steals in three seasons.[4]

In 1986, Richardson was banned for life by NBA commissioner David Stern after testing positive for cocaine for a third time in three seasons. He was the first active NBA player to be banned by the league. He was reinstated by the NBA in 1988, but decided to continue his career in Europe and never played in the NBA again. Richardson later became a head coach in the Continental Basketball Association (CBA) and National Basketball League of Canada (NBL Canada).

Remove ads

Early life

Richardson was born on April 11, 1955, in Lubbock, Texas,[5] the son of Billy Jack Richardson and Luddie Hicks.[6] Richardson was a 1974 graduate of Manual High School in Denver, Colorado. He averaged 10 points on a talented team and did not start for the varsity team until he was a senior. Richardson played on the 1972 state championship team.[7]

College career

Summarize

Perspective

Richardson played collegiately at the University of Montana. He was recruited to the Big Sky Conference school by Hall of Fame coach Jud Heathcote after Richardson's Denver basketball friend David Berry had visited the school.[8] As a freshman in 1974–1975, the Grizzlies went 21–8 and qualified for the 1975 NCAA Division I Basketball Tournament, as Richardson averaged 7.5 points and 3.6 rebounds. The Grizzlies defeated Utah State 79–63, before losing to the eventual national champion UCLA Bruins 67–64. Montana then lost to UNLV in the regional 3rd place game.[9] Richardson averaged 18.2 points, 6.3 rebounds, and 3.8 assists as a sophomore in 1975–1976, as Montana finished 13–12. After the season, Heathcote left for Michigan State University, where he would win the 1979 NCAA title.[10] Under coach Jim Brandenburg, who had been an assistant under Heathcote, Richardson averaged 19.2 points, 8.6 rebounds, and 3.6 assists as Montana finished 18–8 in 1976–1977.[11] As a senior, Richardson averaged 24.2 points and 6.9 rebounds in 1977–1978, and Montana finished 20–8, capturing the Big Sky regular-season title.[12] In his Montana career, Richardson averaged 17.1 points, 6.3 rebounds, and 3.7 assists on 49% shooting in 107 career games. Richardson was first-team All-Big Sky Conference as a sophomore, junior, and senior.[13] Today,[as of?] Richardson still shares the Montana single-game scoring record of 40 points, and holds the single-game record for field goals of 18 and the single-season scoring average record of 24.2. Richardson is third on the Montana career assists list (372), second in career scoring (1,827 points), and ninth in career rebounding.[14]

Remove ads

Professional career

Summarize

Perspective

New York Knicks (1978–1982)

The New York Knicks selected Richardson with the fourth overall pick in the 1978 NBA draft, and he was promoted as "the next Walt Frazier".[15] Two picks later, the Boston Celtics drafted future Hall of Famer Larry Bird. In his second year, Richardson became the third player in NBA history to lead the league in both assists (10.1) and steals (3.2),[b][5] establishing Knicks' franchise records in both categories.[15] He also recorded 18 triple-doubles, the second-most in franchise history. During the 1980-81 NBA season, Richardson made his second All-Star game, scoring 11 points, grabbing 5 rebounds, and recording 4 steals in a 123–120 Eastern Conference victory.[18] The Knicks eventually finished 50–32 and Richardson made the playoffs for the first time in his career. However, in the first round, Richardson, who averaged 11.5 points, 9.5 rebounds, 5.5 assists, and 3.5 steals per game in the series, and the Knicks lost in an upset to the Reggie Theus-led Chicago Bulls.[19] The following season, on November 27, 1981, Richardson scored his highest single game total as a Knick, with 33 points in a 116–95 win over the Cleveland Cavaliers.[20]

Golden State Warriors (1982–1983)

At the beginning of the 1982–83 season, on October 22, 1982, Richardson was traded to the Golden State Warriors (along with a fifth-round draft choice) in exchange for Bernard King. On February 5, 1983, Richardson recorded a double-double with 10 points and 11 assists, while adding a career-high nine steals, in a 106–102 win over the San Antonio Spurs.[3][21] On February 6, 1983, after playing only 33 games for the Warriors, Richardson was traded to the New Jersey Nets in exchange for Sleepy Floyd and Mickey Johnson.[3]

New Jersey Nets (1983–1986)

In the 1984 playoffs, Richardson led the Nets to a shocking upset of the defending champion Philadelphia 76ers. In the fifth and deciding game, he scored 24 points and had six steals. In the following series, against the Milwaukee Bucks, Richardson led the Nets to a Game 4 victory with a team high 24 points.[22] However, the Nets would ultimately lose the series in six games. In 1985, Richardson was named the NBA Comeback Player of the Year after averaging 20.1 points and leading the league in steals while playing all 82 games, after only playing 48 games in the prior season due to rehabilitating from substance abuse.[23] On October 30, 1985, Richardson barely missed a quadruple-double when he scored 38 points, grabbed 11 rebounds, recorded 11 assists, and tied his career-high with nine steals, during a 147–138 win over the Indiana Pacers.[3][24][25] Richardson wore Leather Converse All Stars briefly with the Nets, making him the last to wear the shoe in any form in the NBA.[26]

NBA ban

On February 25, 1986, Richardson was banned for life by NBA commissioner David Stern after testing positive for cocaine for a third time in three seasons. He was the first active NBA player to be banned by the league.[27] He regained the right to play in the NBA in 1988,[28] but decided to continue his career in Europe.[29] He never played in the NBA again.[30]

Long Island Knights (1986–1987)

Richardson played with the Long Island Knights of the United States Basketball League for two months in 1987.[31][32]

Albany Patroons (1987–1988)

Richardson played with the Albany Patroons of the Continental Basketball Association (CBA) during the 1987–88 season and won the CBA championship.[33]

Europe (1988–2002)

In 1988, Richardson signed with Virtus Bologna, a prominent European team. In 1988–89 Virtus won its third Italian Cup, but it was defeated in the semi-finals for the national championship against Enichem Livorno.[34] Despite the playoffs' elimination, the season was considered a rebirth for Virtus: the national cup was the team's first trophy since 1984 and the great performances of Richardson had brought back the passion for basketball in the city. This period became known as "Sugar-mania", from Richardson's historic nickname.[35][36] Virtus won the Italian Cup again and on 13 March 1990, won its first European title, the FIBA European Cup Winners' Cup, the second-tier level European-wide competition, defeating 79–74 the Real Madrid coached by George Karl. The final was characterized by an outstanding performance of Richardson, able to score 29 points.[37]

He then played for KK Split (1991–1992), Baker Livorno (1992–1994), Olympique Antibes (1994–1997), Cholet Basket (1997–1998), and Montana Forlì (1998–1999). Richardson played for Basket Livorno (1999–2000), Olympique Antibes again (2001) and finally, AC Golfe-Juan-Vallauris (2002) at age 47.[38]

Richardson won the European-wide second-tier level FIBA Cup Winners' Cup, in the 1989–90 season with Virtus Bologna. He won the LNB Pro A championship with Olympique Antibes in 1995.[38]

Remove ads

Player profile

At 6 feet 5 inches (1.96 m) and 189 pounds (86 kg)[3], Richardson was bigger than the average point guard in his era.[15] In 556 career NBA games, he averaged 14.8 points, 5.5 rebounds, 7.0 assists, and 2.6 steals. In 18 career NBA playoff games, he averaged 15.7 points, 7.2 rebounds, 5.5 assists and 2.8 steals.[3] Isiah Thomas said that Richardson was the player that gave him the most problems.[39] "He had it all as a player, with no weaknesses in his game".[5] After Richardson was banned from the NBA in 1986, sportswriter Bob Ryan wrote in The Boston Globe: "At his best, Micheal Ray Richardson is a 6-foot-5-inch (1.96 m) Magic Johnson."[40] Johnson said, "When I was playing, the one player I enjoyed watching more than anyone else was Sugar Ray Richardson. When I saw him, I saw a smaller version of me."[5]

Remove ads

Coaching career

Summarize

Perspective

Albany Patroons (2004–2007)

On December 14, 2004, he was named head coach of the Albany Patroons in the CBA.[41] Richardson had previously played with Albany in 1987–1988, when it won its second CBA championship under coach Bill Musselman.[42]

Supposed anti-Semitic and homophobic comments

On March 28, 2007, Richardson was suspended for the remainder of the CBA championship series for comments in an interview with the Albany Times Union, in which he stated that Jews were "crafty (because) they are hated worldwide."[43] The paper also reported that Richardson directed expletives at a heckler, using profanity and an anti-gay slur, at Game 1 of the championship series.[44] Some sportswriters came to Richardson's defense, in the wake of the incident. Peter Vecsey questioned the Times Union's motives in not releasing the audio recording of their exchange with Richardson. Vecsey noted that during the course of his professional dealings with Richardson, he found the player to be "so unsettled, so unsophisticated and so pliable anybody could draw him into saying anything about anything at any time." He also pointed out that Richardson's second wife was Jewish, as was their daughter, Tamara, something that would be unlikely for a true anti-Semite.[45] Christopher Isenberg, a Jewish writer who had earlier profiled Richardson for the Village Voice,[46] also defended Richardson's remarks about Jews in a blog post entitled "Jews for Micheal Ray".[47] NBA commissioner David Stern, who was Jewish, voiced support for Richardson. While conceding that the remarks about homosexuals were "inappropriate and insensitive" and worthy of a suspension, Stern said, "I have no doubt that Micheal Ray is not anti-Semitic. I know that he's not...He may have exercised very poor judgment, but that does not reflect Micheal Ray Richardson's feelings about Jews."[48] Ze'ev Chafets wrote in the Los Angeles Times that Richardson's comments, while perhaps stereotypical, were not anti-semitic.[49]

Oklahoma/Lawton-Fort Sill Cavalry (2007–2011)

On May 24, 2007, Richardson was named head coach of the reincarnated Oklahoma Cavalry of the CBA.[50] On December 16, 2007, he was fired by the Cavalry, for sticking up for his players when their paychecks bounced, but rehired the next season.[51]

Richardson coached for the relocated Lawton-Ft Sill Cavalry located in Lawton, Oklahoma, winning three consecutive championships in 2008–2010. Richardson led the Cavalry to victory to the Continental Basketball Association Finals in 2008 and 2009 and in the Premiere Basketball League Finals in 2010.[4] Richardson was ejected from the first game of the 2010 Premiere Basketball League Championship Series. The ejection took place with under three seconds remaining in the game, eventually won by Rochester in overtime 110–106. The ejection led to a skirmish between fans and several Lawton-Fort Sill players which ended the game with 2.6 seconds to go on the clock and Rochester about to go to the free-throw line.[52]

London Lightning (2011–2014)

On August 17, 2011, Richardson was hired as the first head coach of NBL Canada's London Lightning.[53] Richardson was named the NBL Canada's first ever Coach of the Month for November 2011, an award he would win again in January 2012.[54] London finished the regular season at 28–8. On March 25, 2012, Richardson led the Lightning to a 116–92 victory over the Halifax Rainmen in the deciding Game Five of the NBL Canada Finals to win the NBL Canada's inaugural championship. After the game, Richardson was named the NBL Canada Coach of the Year for 2011–12.[55] On April 12, 2013, Richardson led the London to an 87–80 victory over the Summerside Storm and the team became back to back NBL champions.[56] Richardson left the London Lightning following the 2013–14 season to pursue coaching positions closer to home.[57]

Remove ads

Honors

NBA career statistics

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| * | Led the league |

Regular season

Playoffs

Remove ads

NBL coaching record

Personal life and death

Richardson lived in Lawton, Oklahoma. He had 11 grandchildren. Richardson put on youth basketball clinics with Otis Birdsong, his longtime friend and former teammate. He worked for a financial firm, and he and his wife, Kimberly, owned a beauty salon.[58] His son, Amir Richardson, is a professional soccer player who represents ACF Fiorentina of the Serie A and the Morocco national team.[61]

He changed the spelling of his first name from "Michael" to "Micheal" in 1983.[1]

Richardson was the subject of the TNT Network 2000 film Whatever Happened to Micheal Ray?, narrated by Chris Rock.[62][63] His memoir, Banned: How I Squandered an All-Star NBA Career Before Finding My Redemption, was published in 2024.[5]

Richardson died in Lawton on November 11, 2025, at the age of 70, following a diagnosis of prostate cancer.[4]

Publications

- Richardson, Michael Ray; Uitti, Jacob (2024). Banned: How I Squandered an All-Star NBA Career Before Finding My Redemption. Sports Publishing. ISBN 9781683584902.

See also

Notes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads