Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Economy of the Ming dynasty

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The economy of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) was the largest in the world at the time, with China's share of the world's gross domestic product estimated at 31%,[1] and other estimates at 25% by 1500 and 29% by 1600.[2] The Ming era is considered one of the three golden ages of China, alongside the Han and Tang dynasties.

The founder of the Ming dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor, aimed to create a more equal society with self-sufficient peasant farms, supplemented by necessary artisans and merchants in the cities. The state was responsible for distributing surpluses and investing in infrastructure. To achieve this goal, the state administration was reestablished and tax inventories of the population and land were conducted. Taxes were lowered from the high levels imposed during the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The government's support for agricultural production and reconstruction of the country resulted in surpluses, which were then traded in markets. This also led to the emergence of property differentiation and the growing political influence of large landowners (gentry) and merchants, ultimately weakening the power of the government.

During the middle Ming period, there was a gradual relaxation of state control over the economy. This was evident in the government's decision to abolish state monopolies on the production of salt and iron, and to privatize these and other industries such as textiles, porcelain, and paper mills. This led to the establishment of numerous private enterprises, some of which were quite large and employed hundreds of workers who were paid wages. In the agricultural sector, there was a growing trend of farms specializing in crops for the market, with different regions focusing on different crops. This also led to the expansion of market-oriented enterprises that grew crops such as tea, fruit, and industrial crops like lacquerware and cotton on a large scale. This regional specialization in agriculture continued into the Qing dynasty. Additionally, there was a shift from paying taxes in the form of products and labor obligations at the beginning of the dynasty to paying them in monetary form over time.

In addition to internal trade, foreign trade also flourished during the Ming era, but it was heavily regulated by the government in the first two centuries. The conservative attitudes of the government towards foreign trade in the early 16th century did not affect its volume, but rather led to its militarization. Eventually, China opened up connections with Europe and America and lifted government prohibitions, becoming a central hub in the global trade network. However, there were still disparities in economic development among different regions of China. As trade routes and economic centers shifted, regions such as Sichuan, Shaanxi, and others lost their significance.[3] The decline of the Silk Road also resulted in the decline of cities like Kaifeng, Luoyang, Chengdu, and Xi'an, which were no longer on the main trade routes.[3] On the other hand, the southeastern coastal provinces and areas along the Yangtze River and Grand Canal experienced significant growth. New cities emerged along these waterways, including Tianjin, Jining, Hankou, Songjiang, and Shanghai.[3] The most populous cities during the Ming dynasty were Beijing and Nanjing, as well as Suzhou, which served as the economic center of China.

Towards the end of the Ming era, natural disasters and the onset of the Little Ice Age caused a significant decline in agricultural production, particularly in the economically weaker northern region of China. As a result, the regime was unable to guarantee the safety and well-being of its population, leading to a loss of legitimacy and ultimately, its collapse due to peasant uprisings.

Chinese units of measurement[4]

Length:

- 1 li (里) = 559.8 meters

Area:

- 1 mu (畝) = 580.32 square meters.

Weight:

- 1 liang (两) = 37.301 grams.

- 1 jin (斤) = 596.816 grams.

Capacity:

- 1 dan (石) = 107.4 liters,

- 1 dou (斗) = 10.74 liters.

Currency:

- 1 guan (貫) = 400 wen (copper coins).

Remove ads

Geography and society

Summarize

Perspective

Geography

Ming China was geographically divided into distinct regions, with the main division being between the north and south, roughly along the Huai River. In the northern region, agriculture was centered around the cultivation of wheat and millet, leading to the consolidation of fields into larger estates. Peasants lived in compact villages that were connected by a network of land routes. The wars that resulted in the establishment of the Ming dynasty caused a decline in population in the north, which allowed for greater control by the authorities through the dense network of counties and prefectures. The Grand Canal, which was restored in the early 15th century, played a significant role in the economy of the north, with several cities growing along its route. In the 1420s, a new metropolis emerged in Beijing, accompanied by a large army of several hundred thousand men stationed in and around the city and on the northern border of the country.[5] In terms of transportation, the north relied on relatively slow methods such as carts and horses, while the south benefited from the abundance of canals, rivers, and lakes, which allowed for faster and cheaper transportation of goods by boat.[6]

In the south, rice was the main crop, requiring significantly more human labor. Growing seedlings, planting, weeding, and harvesting were all done manually, with draft animals only used for plowing.[7] The most developed region in the south, and in all of China, was Jiangnan, which roughly encompassed Zhejiang Province and the southern part of what was then Nanzhili (present-day Anhui and southern Jiangsu).[5] While the provinces of Jiangxi and Huguang also supplied rice to Jiangnan, areas outside of the waterways remained relatively undeveloped. During the Ming era, Jiangxi lost its former importance and its inhabitants moved to Huguang due to overpopulation. The center of Huguang also shifted from Jiangling (present-day Jingzhou) to Hankou.[8] In Fujian, the urban elite became wealthy through maritime trade, as the lack of land there led to a focus on trade. Guangdong remained weakly connected to the developed regions of China for most of the Ming period. Sichuan was a relatively independent peripheral region of the empire, while Yunnan and Guangxi were of minor importance.[9]

Population

The economic development of the country was heavily influenced by factors such as population size, population density, and the availability and cost of labor. Due to a lack of reliable data, there is ongoing debate among historians about the exact population size during the Ming era. While censuses from the 1380s and 1390s are considered somewhat trustworthy, they only account for 59–60 million people, excluding soldiers and other groups. Based on these figures, 20th-century historians have estimated the population of Ming China at the end of the 14th century to be between 65–85 million.[a]

During the centuries of internal peace that followed, the population of China experienced significant growth. According to editors of county and prefectural chronicles, the population may have tripled or even quintupled since 1368, reaching its peak in the second half of the 16th century.[14] Modern historians have varying estimates of the population during this time period. John Fairbank suggests 160 million[15] inhabitants by the end of the Ming era, while Timothy Brook writes of 175 million[14] and Patricia Ebrey gives a figure of 200 million.[16] Frederick Mote estimates a population of 231 million by 1600 and 231 to 268 million by 1650.[17] While there is some disagreement among historians, it is clear that the population grew significantly between the late 14th and early 17th centuries. Despite a decline of one-sixth to one-quarter[18] due to peasant uprisings, epidemics, and the Manchu invasion, a new census taken fifteen years after the fall of the Ming dynasty still counted approximately 105 million people.[19]

During the last century of the Ming era, overpopulation led to a decline in living conditions, resulting in increased mortality rates and a decrease in population growth rates and life expectancy in most provinces. This also caused a widening gap in life expectancy between the lower and upper classes of the population.[20] Towards the end of the Ming era and the beginning of the Qing period, there was a reversal of these trends in some provinces, as the population sharply declined.

The settlement of Ming China was characterized by significant disparities. In order to address this issue, the first Ming emperor, Hongwu Emperor, relocated up to 3 million people, primarily to the underpopulated northern regions. These settlers mainly originated from Shanxi, which had been less affected by the wars. In the south, the Hongwu Emperor also encouraged people from the coastal regions of Fujian and Zhejiang to move inland.[21] Additionally, there was independent migration to the western borderlands of Henan, from the lowlands of Jiangxi to its mountainous areas, and from Jiangxi to Huguang. Settling in these originally sparsely populated regions also had the benefit of lower taxes, as tax quotas for these areas remained low for an extended period of time, regardless of population growth.[22]

According to calculations by American historian and sociologist Gilbert Rozman, at the start of the 16th century, approximately 6.5% of China's population of 130 million resided in cities.[23] The two most populous cities were the capital cities of Beijing and Nanjing, as well as Suzhou, which served as the economic hub of the Ming dynasty. During this time, Beijing had a population of nearly 1 million, Nanjing had over 1 million, and Suzhou had less than 650,000.[3] Other significant economic centers in the country included Hangzhou and Foshan.[24]

Remove ads

Agriculture

Summarize

Perspective

Climate

In pre-industrial societies, agriculture served as the foundation and mainstay of the economy, upon which crafts and trade relied. The production of crops and livestock was greatly influenced by weather patterns and, over time, the effects of climate change.[25] Additionally, natural disasters such as droughts, floods, and epidemics had a significant impact on the overall functioning of the economy.

The Ming period was generally drier than the preceding Yuan era. Winters were cold from 1350 to 1450, with warmer springs beginning around 1400.[26] On average, the temperature was one degree lower than in the second half of the 20th century. The most severe natural disasters during this time were floods in 1353–1354 in northern China, Zhejiang, and Guangxi, as well as in the 1420s in Shanxi.[27]

From 1450 to 1520, there was a drier period characterized by warm springs and winters, although winters did cool down after 1500.[27] Overall, the average temperature remained stable, but the north experienced occasional droughts while the south was plagued by floods. The most severe droughts were recorded in 1452 (in Huguang) and 1504 (in northern China), while the worst floods occurred in 1482 (in Huguang). In 1484, the entire country was hit by an extraordinary drought, and the following years (1485–1487) saw perhaps the greatest disaster of the Ming era: epidemics in northern China and Jiangnan. The south also suffered from floods during 1477–1485.[28]

Between 1520 and 1570, the climate was cooler and wetter, with warmer winters towards the end. The average temperature was 0.5 degrees lower than the previous period. Droughts affected the Yangtze River basin, particularly in Zhejiang, Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Hubei, where the worst drought of the Ming era occurred in 1528. The years 1568 and 1569 also saw extreme weather conditions, with both droughts and floods occurring.[28]

From 1570 to 1620, the climate was relatively warm, especially in winter, with an average temperature one degree higher than the previous period. The weather, however, was generally drier, with occasional floods. The most significant disasters during this time were the floods in the north in 1585, followed by a major epidemic in 1586, a country-wide drought in 1589, and droughts in the second decade of the 17th century in Fujian and the north. The year 1613 saw major floods throughout the country.[28]

The period from 1620 to 1700 was characterized by colder temperatures and occasional wetter conditions. A drought in the 1630s in the north was followed by epidemics and floods from 1637 to 1641, and another drought in 1640–1641. Temperatures were a degree lower than the previous period, especially towards the end of the century.[28]

Village life

Thanks to the efforts of previous generations, Chinese agriculture had reached a relatively high level. The peasants had extensive knowledge and utilized various techniques such as vernalization, crop rotation, careful fertilization, and irrigation. They also had special methods for cultivating different types of soil and took into account the relationships between crops. In fact, they even grew different crops in the same field.[29] By 1400, artificial irrigation was widespread, covering 30% of cultivated land (equivalent to 7.5 million hectares out of a total of 24.7 million hectares).[30] During the Ming period, there was an increase in the planting of industrial crops, particularly cotton.[29] This led to the replacement of hemp clothing with cotton clothing.[31]

Farmers introduced new varieties of rice, with some varieties maturing in as little as 60 days and others in 50 days, allowing for multiple harvests per year. The original Chinese rice took 150 days to mature after being transplanted at 4–6 weeks of age, while the Champa rice imported in the early 11th century took 100 days.[23] The government had previously promoted crop rotation and the introduction of wheat as a second crop during the Song dynasty, but the practice of double rice harvests was slow to spread.[32]

In the 12th century, Chinese farmers were able to achieve impressive yields, harvesting ten times the amount of wheat and barley that was sown. This was even more impressive for rice. In comparison, medieval Europe only saw yields of about four times the amount sown, and it was not until the 18th century that Europeans were able to increase this ratio.[23] Despite their success, Chinese farmers continued to use simple and primitive tools. This was due to the low cost and availability of labor, which reduced the need for technological advancements.[29]

Rice, which had been the staple food for the poor since the Song dynasty (960–1279),[33] was gradually joined by the American sweet potato, which was introduced to China around 1560.[34] The Columbian exchange also brought other crops from the Americas, such as corn, potatoes, and peanuts, which led to an increase in the amount of cultivated land. This was especially beneficial for land that was unsuitable for traditional Chinese crops.[23] The new crops, along with wheat, rice, and millet, were able to provide food for the growing population of China.[35][36] The weight of rice in the diet of the population slowly declined and was still around 70% at the beginning of the 17th century. It was not until later centuries that American crops became more widespread.[b]

Early period

The first Ming emperor, Hongwu Emperor, aimed to create a Confucian-based economy that prioritized agriculture as the main source of wealth.[38] He envisioned a society where peasants lived in self-sufficient communities and had minimal interaction with the government, aside from paying taxes. To achieve this, the Emperor implemented various measures to support the peasants.[39] The late Ming official Zhang Tao reflected on the early Ming period with assurance in the Emperor's accomplishments:

Every family was self-sufficient, with a house to live in, land to cultivate, hill from which to cut firewoods, and gardens in which to grow vegetables. Taxes were collected without harassment and bandits did not appear. Marriages were arranged at the proper times and the villages were secure. Women spun and wove and men tended the crops. Servants were obedient and hardworking, neighbors cordial and friendly.

— Zhang Tao, Gazetteer of Sheh County, 1609[40]

During the wars that established the Ming dynasty, there was a significant expansion of state ownership of land. This was achieved through the confiscation of land from opponents of the new dynasty, as well as the return of state-owned lands from the previous Yuan and Song dynasties.[38] Additionally, the Ming government also confiscated the vast land holdings of Buddhist and Taoist monasteries. To regulate the power of these religious institutions, the Ming government imposed a limit of one monastery per county, with a maximum of two monks per monastery. Redundant offices were also abolished, and hundreds of thousands of monks were forced to return to secular life.[41] Overall, the state owned two-thirds of cultivated land,[42] with private land being more prevalent in the south and state-owned land in the north.[38]

During the wars, those who abandoned their estates were not entitled to have them returned. Instead, they were given replacement lands, but only if they intended to work on them themselves.[43] Those who occupied more land than they could cultivate were punished with flogging and had their land confiscated. The restrictions on large landowners also applied to the new Ming dignitaries, ministers, officials, and even members of the imperial family.[44] They were only allowed to receive income in the form of rice and silk, rather than being granted land.[41]

Most state land was divided into plots and given to peasants for permanent use.[38] In the north, peasants were allocated 15 mu per field and two per garden, while in the south, the allocation was 16 mu for peasants and 50 mu for soldier-peasants.[41] (During the Ming era, 10 mu was equal to 0.58 hectares.) Peasants who farmed state land were allowed to pass it on to their descendants, but were not permitted to sell it. Essentially, the Tang system of equal fields was restored.[42]

The government created lists of residents and their property, known as the Yellow Registers, for tax purposes. Land ownership was recorded in the Fish-Scale Map Registers.[38] On state-owned land, peasants had higher duties compared to private land, and they also paid high rents to landowners.[45]

In order to revive the country's economy after years of war, the government provided support for agricultural production through various means. This included investing in infrastructure, restoring dams and canals, and reducing taxes.[46] The government also organized resettlement from the densely populated south to the devastated northern provinces, initially through involuntary means. However, later on, the government stopped the forced relocation of people.[47] Settlers were not only given land, but also received planting materials and equipment, including draft animals.[46] Farmers on newly cultivated land were given tax breaks. In borderlands and strategically important areas, villages of soldier-peasants were established. These villages were responsible for supplying the army with food and were also required to serve in the military in times of war.[38]

Privatization and concentration of assets

The Hongwu Emperor's idea of a countryside made up of small farmers paying state taxes was never fully realized. As time passed, many peasants lost their land to powerful and wealthy landlords, who then charged them rent. Meanwhile, the peasants were still required to pay taxes at the original amount.[45] This was due to the fact that many powerful individuals were exempt from paying taxes on their land, and the property of officials and members of the dynasty was also not included in tax rolls. As a result, the government had to find other ways to generate income. This often involved providing relief, such as tax exemptions for newly cultivated fields or previously uncultivated land in areas like wastelands, swamps, and salt mines.[45]

Small farmers were struggling to support themselves and were losing their land to moneylenders and landlords. State-owned land was also being sold, but due to the illegal nature of the sales, it was being sold at a significantly lower price.[48] These sales were often manipulated by village elders and lower-ranking officials, who had the ability to alter official records and registers.[49] As a result of mass resettlement and the population's efforts to avoid heavy taxes, there was a growing number of homeless individuals searching for land to rent or any type of work, as well as artisans and traveling merchants.[50] During the middle Ming period, the government abandoned their attempts to return these wandering individuals to their home villages and instead ordered local authorities to register and tax them in the place where they currently resided.[51] This ultimately led to the reestablishment of wealthy landowners and merchants dominating over tenants, servants, and temporary migrant workers, which was a far cry from the ideal of the Hongwu Emperor—a strict adherence to a stable hierarchy of the "four occupations" (in descending order): officials, peasants, artisans, and merchants.[52]

Those who went out as merchants became numerous, and the ownership of land was no longer esteemed. As men matched wits using their assets, fortunes rose and fell unpredictably. The capable succeeded, the dull-witted were destroyed; the family to the west enriched itself while the family to the east was impoverished. The balance between the mighty and the lowly was lost as both competed for trivial amounts, each exploiting the other and everyone publicizing himself.

— Zhang Tao, Gazetteer of Sheh County, 1609[53]

By the end of the 15th century, the wealth and political influence of large landowners had grown disproportionately, while the lives of small farmers became increasingly difficult.[29] Both state-owned and private land that had previously been used by small farmers now belonged to the wealthy. This new wealthy class consisted of members of noble families, officials, high-ranking officers, wealthy merchants, burghers, and administrators of large feudal estates; some individual estates were even as large as half a district.[54]

Some successful farmers emerged from the originally homogenous peasant farms, while others fell into poverty and had their land acquired by their wealthier neighbors, who were also involved in local government, or by creditors.[54] Contemporary sources described the state of the countryside with the following words:

There were only a few who actually managed the village, but there were many who took bribes.

— [54]

Land privatization was most prevalent in the economically developed provinces of Jiangxi, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Hunan, and Hubei.[54] In the borderlands, military commanders and other influential individuals acquired land from military settlements. While officials expressed concerns about dishonest means of land transfer, they themselves were part of the wealthy landowner class and only offered rhetorical condemnation of these processes. As a result, former peasants who became tenants continued to bear fees and obligations to the state. The main beneficiaries of land acquisition were members of the imperial family, relatives of the emperor in the female line, and eunuchs, who seized both state and private lands with the consent of the throne on a large scale. Starting in 1456, emperors also began to establish their own personal estates from state lands, with the number reaching three hundred by the end of the Ming dynasty. Five of these estates, located in the capital area, encompassed over a million mu of land. In the late 15th century, princes and other members of the imperial family also began to build large estates, with those closest to the emperors amounting to millions of mu. Meritorious dignitaries were also granted land by the emperor, typically in the range of tens and hundreds of thousands of mu. These grants often included peasants who still held land from the state, as well as private owners who were converted into tenants.[55]

In the southern provinces by the end of the 16th century, most of the original state land had been transferred to private ownership, with the exception of a small amount reserved for schools.[56] Unlike in the north, where small farmers were often violently evicted and had their property confiscated, the transition to tenancy in the south was less brutal.[57]

Large estates were typically divided into smaller plots and rented out to individual families, with the landlords relying on the rent for their income and showing little concern for the well-being of the peasants or the productivity of their labor. As a result, there was little incentive to improve technology or hire wage labor, as the landlords could simply rely on the forced labor of their tenants. This made the estates a conservative force in society.[55]

The lords collected payments from their tenants, but they were often exempt from taxes. This resulted in a decrease in state revenues, which was addressed by shifting the tax burden onto the rest of the population. This shift in taxes, along with the subservience to new lords, had negative effects on wealthy peasants and landowners who still held onto their land and implemented more efficient farming methods. As a result, the process of "feudalization" hindered modernization in the countryside.[55]

An example of an active small landowner who was also a tenant, devoting unceasing attention to soil improvement through fertilizers, was Zhang Lüxiang, author of Bu Nongshu (Supplement to the Agricultural Manual, 1658). This work expanded upon the writings of his relative, Shenshi Nongshu (Master Shen's Agricultural Manual).[58]

The main labor force consisted of tenant farmers and free peasants, with less reliance on wage labor. However, these farms were primarily focused on producing goods for the market, such as vegetables, fruits, flowers, industrial crops, cotton, tobacco, lacto-bearing trees, and fish.[55]

Tax increases, peasant escapes and uprisings

The colonies of soldier-peasants were on the verge of disappearing, leading to a significant decrease in the state treasury's income from military settlements. Originally, these settlements contributed almost two-thirds of the state's income from agriculture, but now it had fallen to only one-tenth of its original size. This decline also resulted in the disintegration of the small peasant class who directly paid taxes to the state. Instead, they were replaced by dependents of large landowners. These tenants were no longer direct taxpayers, but rather fulfilled tax obligations for their lords. They paid rent amounting to half of their harvest, and also had to fulfill various customary labor obligations.[59]

With the dwindling number of peasant taxpayers and the increasing number of people relying on the state treasury, the Ming authorities faced a shortage of revenue. Even attempts to raise additional revenue, such as the sale of Buddhist temple lands, were not enough.[57] The emperors' efforts to increase revenue were also met with resistance from within the state apparatus. During the Wanli era (1573–1620), eunuchs who were responsible for collecting fees and taxes faced opposition from local officials, sometimes resulting in imprisonment or even death.[60]

Merchants were able to evade various additional charges and fees by shifting markets and trade routes. As a result, the only option left was to increase taxes on farmers, causing the taxes on private land to reach the same level as those on state land. This naturally led to discontent among the population.[57]

Peasants who lost their land, especially in the northern and central provinces, fled to the mountains and became bandits. Large-scale uprisings also occurred, such as the peasant revolt that began in 1507 in the provinces of Hubei and Hunan and lasted until 1512. In 1513, an uprising broke out in Jiangxi Province, with rebel detachments reaching tens of thousands of fighters and spreading into the provinces of Zhejiang and Fujian. Prolonged unrest also affected the provinces of Sichuan and Shandong. These peasant movements were typically spontaneous and disorganized, lacking clear goals or slogans. The peasants' struggle was against oppression by local authorities, landlords, and moneylenders, and was sometimes supported by miners, soldiers, and urban poor. These movements were often led by educated but unsuccessful members of the middle class.[57]

Revolts were most common in Shaanxi, Gansu, Shandong, and parts of Henan provinces. In southwestern China, the Miao and Yao ethnic groups also resisted the Ming regime for many years. Despite occasional concessions, such as tax reductions and amnesties, the tide of peasant unrest continued to rise.[57] Eventually, in 1644, Li Zicheng's rebel army overthrew the government in northern China and captured Beijing.

Remove ads

Crafts and industry

Summarize

Perspective

Initial period—state organization of production

The urban artisans were closely monitored by the state and were required to be registered on lists, making it difficult for them to move without the authorities' knowledge. This also made them easily accessible to officials who enforced their obligations to the state.[62] Some industries, such as porcelain factories, were nationalized, and the state held a monopoly on the mining and processing of salt and ores, leading to high prices for these metals.[63] In addition to paying taxes, artisans were also required to fulfill a work obligation, which could be extremely burdensome if it had to be performed away from home.[45] Although this work obligation was gradually replaced by monetary payments, it was not completely eliminated by the end of the dynasty.[64]

Along with the rise of new crafts, new guilds also emerged, while existing ones became more specialized and divided.[62] By the end of the Ming dynasty, there were approximately 100 guilds in county towns and cities of similar size.[65] However, the process of separating trade from crafts was a slow one and continued until the 20th century. Each production operation had its own separate guild, and semi-finished products were passed between them through merchants. This division of production stages had a negative impact on the overall development of the industry.[62] One of the weaknesses of Chinese guilds was their limited political influence, as they were under the control of the authorities and only had power over their own members. As the domestic market expanded and supraregional relations grew, the importance of guilds declined. In response, merchants formed their own territorial organizations known as huiguan.[64]

Development of private entrepreneurship

In the 14th century, production began to spread out to households. This method of organizing production was most common in silk and cotton industries in the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang. For example, in the Puyuan area of Zhejiang, the market was dominated by four merchant associations. These associations rented out looms to weavers in both urban and suburban areas, provided them with raw materials, and purchased their finished products. By the 16th century, some towns and villages along the lower Yangtze River were primarily inhabited by spinners and weavers, with agriculture playing a secondary role. The relationship between small producers and merchants varied, ranging from simple buying and selling to renting out workshops and equipment, and even dispersed manufacturing.[66] Silk production was divided into four distinct sectors: mulberry cultivation for leaves, silkworm breeding, raw silk spinning, and silk fabric weaving. The market played a crucial role in regulating supply and demand.[67]

In the silk industry of Suzhou, Nanjing, and Hangzhou, privately owned workshops with hired workers emerged. Some were small, but others employed several hundred workers, and division of labor was a common feature in the production process. However, these large enterprises were later targeted by a law enacted by the Shunzhi Emperor (r. 1644–1661) of the Qing dynasty, which prohibited workshops from having more than one hundred machines.[66] In Zhejiang, there were hundreds of dyeing workshops with hired workers, while in Jingdezhen, wealthy merchants commonly owned several kilns for the production of porcelain (in total, there were 200–300 kilns in the city by the end of the 17th century, each manned by about ten workers).

The country's most developed industries were silk weaving, cotton weaving, dyeing, ceramics and porcelain production, and paper and printing. Former silk weaving centers in the interior like Chengdu losing their significance to cities like Nanjing, Suzhou, and Hangzhou.[3] The manufacturing industry also saw significant growth, with the establishment of sugar factories, tea and tobacco processing workshops, and oil pressing facilities. Additionally, there was a boom in the construction industry during the 15th century, with extensive building projects taking place in Beijing and Nanjing. This included the completion and restoration of the Great Wall and other fortresses.[62]

Mining and processing of mineral resources have expanded, accompanied by technical improvements. For example, in coal mining in Hebei, Jiangsu, and Shanxi, a drainage system was implemented and gas was removed from shafts using bamboo pipes. Additionally, miners developed complex lifting mechanisms to extract ores from mines. In smelting, a combination of hard coal and charcoal was utilized.[62]

Iron production surpassed all previous records, with an annual output of 195,000 tons. This exceeded the output of its Song predecessors (125,000 tons per year) and even surpassed the 180,000 tons per year produced in 18th-century Europe, more than a century later. The production of iron was taxed at 1/15th of its total output. The iron products from Guangdong, including farming tools, pots, anchors, cables, sheet metal, wire, and nails, were in high demand and exported throughout Southeast Asia. However, the abundance of highly skilled and inexpensive labor in China also reduced the pressure for technological advancements in this industry.[62]

In the 16th century, the first private capitalist enterprises and factories were established in the most developed areas of China.[64] Private factories and workshops were established around state-owned enterprises, as they utilized the available skilled human resources.[66] The presence of state-owned workshops, particularly armories, textile factories, smelters, and shipyards, where hundreds of thousands of craftsmen were required to fulfill state-mandated labor obligations, posed a significant obstacle and dangerous competition for private enterprise during the early and middle Ming period.[24] Over time, a considerable portion of the industry was privatized, including ironworks, coal and salt mining, steel production, and pottery workshops, all of which had been under state ownership since the Tang dynasty. This led to a rapid growth in production.

One common form of private business during this time was joint ventures among multiple entrepreneurs. These partnerships were often formed due to the limited financial resources of individuals. They were particularly prevalent in industries that were considered risky and challenging for individual entrepreneurs, such as mining, metallurgy, metal processing, salt mining, sugar refining, and paper production. Private companies in these industries were only allowed to operate in remote mountainous areas, far from government officials, due to the state monopoly on mineral extraction and processing. It was not until the mid-16th century that the government began to permit private companies to extract minerals, but they immediately imposed taxes on them. For example, in the Mentougou area near Beijing, coal mines were established by associations of landowners, mine managers, and investors. The workers in these enterprises were paid wages.[64]

During the 16th century, the state workshops underwent reorganization, leading to the abolition of corvée labor and the hiring of employees by the state for a salary. Additionally, the state began to purchase certain raw materials from the market, although at prices set by the authorities. While the primary purpose of state workshop production was to meet the needs of the court and the state, some of it was also sold on the market.[24]

Remove ads

Regional economies

Summarize

Perspective

In the 16th century, different regions of China had distinct focuses in terms of production. For example, Guangdong was known for its production of iron products, Jiangxi for porcelain and ceramics, the Shanghai region for cotton, Wuhu for dyes, and the island of Taiwan for sugar and camphor. Additionally, certain areas within the empire specialized in processing sugar cane, indigo, and oilseeds.[3]

Northern China

The northern region of the country was made up of the provinces of Shanxi, Shaanxi (which also included Gansu at the time), Beizhili, Henan, Shandong, and the northern part of Nanzhili (present-day Jiangsu and Anhui provinces). In this area, agriculture was primarily focused on the cultivation of wheat and millet, which only yielded one crop per year. In some parts of Shandong and Henan, farmers utilized the millet-winter wheat-bean-fallow cycle, which allowed for three crops in two years. Animals played a crucial role in farming, serving as plow animals, transportation, and a source of fertilizer. The ideal farm size was between 100–300 mu (6–17.5 hectares), with a maximum of 400–500 mu (23–29 hectares). This resulted in larger estates and greater social disparities compared to the southern region. To cope with the higher productivity of larger farms, small farmers banded together and jointly owned animals.[68] Medium and large landowners held the majority of the land, with fewer large estates in the most developed areas.[69] These landowners hired workers and stewards, who were often paid in cash. In addition to the large estates, there were also small farmers who earned a living by working on these estates. The middle class was made up of wealthy tenants who were able to rent out their animals. The improvement of agricultural practices and production for the market was largely due to the efforts of small farmers, who saw an increase in wages during the late Ming period.[68]

The northern provinces of Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Gansu primarily imported rice and did not have much to offer the rest of the empire. An exception was the silk industry in Lu'an, Shanxi, which relied on imported raw silk from Sichuan and, to a lesser extent, Huguang. By the Wanli era, this industry was in decline. In the last decades of the Ming dynasty, the cotton industry in Shandong and Shanxi began to develop.[70] Unlike in the south, where cotton growing and processing were separate, in the north, cotton weaving was done by rural cotton farmers.[71] Southeastern Shaanxi (Guanzhong) was known for exporting woolen fabrics, while Henan also exported cotton, with its trade being dominated by Shanxi merchants.[70] These merchants based their wealth on controlling the salt trade and were the second wealthiest merchant group in northern China, after the Huizhou wholesalers from the south.[72]

In Shandong, trade primarily occurred along the Grand Canal, where merchants from different cities would exchange goods. Southern goods, such as pepper, were traded for northern goods like ginseng from Manchuria. The only significant local product in Shandong was cotton. In Jiangsu, cotton cloth was also produced, but it faced competition from weavers in Shandong and Huguang (specifically Xianning and Baling). As a result, Jiangsu turned to exporting its cotton cloth abroad. Dye production was another important industry in Jiangsu, as it was located near textile production centers in Jiangnan. In Anhui, Wuhu was a major supplier of dyes to Jiangnan, while other prefectures in Anhui mainly exported wheat and beans.[73]

Jiangnan

Southern China was known for its wealth and development, particularly in the region of Jiangnan, encompassing roughly the southern part of Nanzhili (present-day Anhui and southern Jiangsu) and Zhejiang.[5] This area was the most economically advanced in the south,[74] with a dense network of cities and a higher proportion of artisans in the population.[69] The use of money was widespread,[74] and the region was known for its high rice yields, much of which was grown for the market.[69] The Huzhou area was renowned for its high-quality silk, which dominated the market (and during the Qing period, it practically dominated the market).[75] Over time, the region shifted from primarily growing rice to cultivating industrial crops such as cotton and mulberries. Rice was imported from the interior via the Yangtze River.[8]

The landowners in this region were increasingly replaced by tenants, who were in turn controlled by a small group of elite rank-holders. These wealthy individuals invested their resources in culture, politics, and education rather than agriculture, and relied on their connections with the authorities. Additionally, merchants from the peripheral prefecture of Huizhou played a crucial role in China's wholesale network, operating throughout the country.[8]

In most of Jiangnan, as well as parts of other southern provinces and Shandong, small farms were the predominant form of agriculture. These farms were often so small that the owners had to supplement their income with other sources. In contrast, larger estates of 5–10 mu (0.29–0.58 ha) were much less common. In the most developed areas of the south, medium-sized farms were the dominant form.[69] According to the Tiangong Kaiwu encyclopedia, a couple could cultivate 25–30 mu on good land, and the optimal farm size for a family with a buffalo was 10 mu, with half that amount for families without one. These medium-sized farms were the majority in the region. In the early Ming period, they were typically owned and operated by independent peasants, but over time, many of these peasants lost their land and became tenants. Even the larger estates in the south were smaller than those in the north, with few exceeding 2–2.5 thousand mu (116–120 ha) by the end of the 16th century. However, there were still many wealthy peasants who owned several dozen mu of land.[76] In the late Ming era, most land was rented, with tenants often renting from multiple owners while also owning their own land.[77]

Fujian

Fujian was a densely populated province with a strong focus on commerce and small-scale production, as well as a thriving overseas trade industry.[78] In the 16th century, the introduction of new varieties of Annam rice led to a significant increase in agricultural productivity, allowing for double harvests.[79] Despite these advancements, the province remained overpopulated and the introduction of new crops, such as sweet potatoes, did little to alleviate the issue in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.[78] As a result, many people were forced to leave the interior of the province and turn to trade as a means of survival, particularly in the 16th century. The high cost of food also led to a decline in cotton and silk cultivation in the southern part of the province during the 17th century.[79]

An unusually large proportion of the province's land was held by soldier-peasants. They received the standard 25–30 mu from the government, which was more than they needed to survive in Fujian. Additionally, Buddhist monasteries also held a significant amount of land, sometimes up to hundreds of mu. According to contemporary authors, in some counties, these monasteries owned the majority of the land. Both soldier-peasants and Buddhist monasteries were exempt from taxes until 1564. In practice, they acted as nominal owners and leased the land to tenants, often merchants, as an investment. These tenants then subleased the land to the peasants.[80] This unique system resulted in Fujian having a high proportion of absentee landlords, who received rent but lived in the cities, and a strong entrepreneurial spirit among the tenants.[81]

Fujian's trade was primarily focused on overseas markets and involved products from other provinces.[79] However, there were some exceptions, such as investments in shipbuilding, townhouses, and education.[80] In particular, sugar production had already become a significant industry in Xinghua Prefecture before 1500, and pottery production had reached a high level. Additionally, paper was exported from Yanping and Jianning, which were also home to iron and silver mines. Silk production was a specialty of Changzhou, while Jinjiang (in Quanzhou Prefecture) was known for its tea. Technological advancements in the 1500s allowed Fujian to rival the traditional silk production centers of Suzhou and Lu'an. In the late Ming period, tobacco also became a major industry in Fujian, along with cotton production in Hui'an.[81]

Jiangxi

The lowlands in the north of Jiangxi Province have been known as a major rice exporter since the pre-Ming era,[58] but the southern mountainous region of the province has remained underdeveloped and self-sufficient. While the north exported rice to Jiangnan, the area suffered from overpopulation despite efforts to reclaim marshy land. As a result, many people migrated to the southern part of the province, and even more so to Huguang. Initially, taxes were low in these newly settled counties because the old tax system established since the early Ming period persisted rigidly, but as time passed, the authorities began to register immigrants in tax records.[82]

Jiangxi was known for importing textiles, specifically silk from Zhejiang and cotton from Jiangnan and later Huguang. The southern region of the province was responsible for exporting rice, while Ganzhou also exported indigo. Additionally, Jingdezhen and later Fuliang and Raozhou were known for their ceramic exports.[73] Jingdezhen had a reputation for producing high-quality porcelain even before the Ming era. While initially state-owned, the production of porcelain became mostly private during the second half of the Ming era.[82] By the end of the 16th century, it was estimated that Jingdezhen had produced 36 million pieces, valued at 1.8 million liang of silver.[83] Ming porcelain was highly sought after in East and Southeast Asia, as well as in Europe.[3] The area surrounding the porcelain factories remained largely undeveloped, with the exception of fuel supplies. Other natural resources, such as bamboo, medicinal herbs, and tea, were also exported from the mountainous regions of southern Jiangxi.[83]

Huguang

At the beginning of the Ming dynasty, Huguang was sparsely populated, leading to an influx of immigrants from Jiangxi and Jiangnan. The tax system, designed for a smaller population, proved advantageous as the population grew.[83] This growth also led to an expansion of agricultural land, prompting the authorities to initiate a series of extensive flood control projects in the northern part of the province (Hubei) after 1400. In contrast, flood control structures in the south (Hunan) were primarily built by local gentry and focused around Dongting Lake.[84] As the population increased, the province became a major exporter of rice by the mid-15th century.[83] This rice was produced as surplus by landowners who collected rents from their tenants. Additionally, the province began exporting cotton fabrics.[85]

From the early 16th century onwards, the gap between the rich and the poor in Huguang grew. The original taxpayers became poorer and developed an aversion to immigrants who did not pay taxes. At the same time, the rich landowners exerted pressure on the tenants through control of drainage works, putting them in a worse position than elsewhere. In the peripheral areas of the province, where official control was weak and transportation was poor, the large landowners built up extensive estates. These estates were settled by immigrants and controlled by private armed groups, creating a specific "frontier" society. This was especially prevalent in the south and west, where clashes between the Chinese and ethnic minorities occurred.[85] After the Single whip reform and Zhang Juzheng's revision of the cadastre, the economic and social status of the population stabilized, but this stability also led to the growth of power for the large landowners.[86] As a result, immigration subsided.[84]

Guangdong and the southwestern provinces

Guangdong, Guangxi, and Sichuan had limited involvement in transregional trade.[85] Due to its borderland nature, Guangdong developed a unique form of land tenure where wealthy tenants sub-leased the land. The province was known for its fortified villages, which were home to closely-knit clans whose leaders acted as their representatives before the authorities.[87] As a result, families had little direct interaction with the state.[9] While rice yields were high at 7–8 dan per mu per year, other crops such as sugarcane were more profitable, yielding 14–15 liang of silver per mu.[80]

During the 15th century, textile mills were established in the province, importing silk and cotton from Jiangsu and Anhui. In the Jiajing era, rice was also imported from Guizhou and Huguang to Guangdong.[80] Tobacco cultivation began in the 16th century, while tea production also saw growth. The ironworks in Foshan played a significant role in exports.[87] The Pearl River Delta, with Guangzhou as its center, experienced economic growth from the early 16th century and became involved in foreign trade by the middle of the century. This led to a significant increase in the population of Guangzhou, from 75,000 in the early Ming period to 300,000 in 1562.[80]

Remove ads

Trade and transportation

Summarize

Perspective

Early Ming commercial and consumption regulations

In the early Ming dynasty, during a time of devastation caused by wars against the Mongols, the Hongwu Emperor implemented strict regulations on trade. He strongly believed in the traditional Confucian perspective that agriculture was the cornerstone of the economy and the primary source of value creation. As a result, he prioritized this sector over others, including trade. The Emperor made efforts to diminish the power of wealthy merchants, such as imposing high taxes on Suzhou and its surrounding area in southeastern Jiangsu, which was the main commercial and economic hub of China at the time.[88]

Only registered merchants were permitted to travel within the empire.[45] To prevent unauthorized business, traveling merchants were required to report their names and cargo to local agents, who were inspected by the authorities on a monthly basis.[89]

According to the laws of the Hongwu Emperor, merchants were closely monitored by the authorities and were required to obtain licenses for travel and trade.[45] The authorities also established fixed prices for most goods, and failure to comply with these prices was punishable.[90] Merchants who sold poor quality goods were subject to confiscation and whipping. The early Ming dynasty also imposed restrictions on consumption, particularly among the wealthy and privileged, out of fear that excessive competition would harm social cohesion and undermine the state's social and economic foundations. These restrictions were justified by Confucian morality, which rejected material interests and selfishness.[91] For the first time in Chinese history, limits on consumption were imposed on each social class.[92]

The anti-trade policy was justified by the Confucian concept of ren (仁; humanity), which was seen as opposed to the perceived immorality, greed, and avarice associated with trade.[93] The market and pursuit of profit were viewed as morally and politically objectionable. The short duration of the Yuan dynasty, which saw a flourishing of international trade, was also cited as evidence against trade.[94] In line with this anti-trade sentiment, the early Ming rulers distanced themselves from any actions that could be seen as corrupt or commercial.[95] As a result, trade was not considered a part of foreign relations, which were instead seen as a means of spreading morality and humanity.[93] Confucian scholars argued that political power was derived more from moral qualities than economic or military power. Additionally, trade based on equal parties was viewed as degrading, as it placed them on the same level as barbarians, leading to a preference for tribute instead.[95]

Transportation

The efficient administration of the country necessitated the constant movement of people and goods. Officials were required to travel between the capital and the regions, while subjects were expected to perform their duties hundreds of kilometers away from their homes. As a result, it was crucial to ensure the smooth supply of both the capital and the regions. To address these challenges, the government established three offices: the courier service (yichuan), the postal service (jidi), and the transportation service (diyun). These offices were responsible for maintaining the state of communications.[96]

The Hongwu Emperor believed that only government couriers and small peddlers should be allowed to travel further from their homes. Despite the Emperor's efforts to enforce this belief, the establishment of an efficient communication network for military and government officials ultimately led to the growth of trade. During the middle Ming period, merchants were already traveling long distances and even bribing courier officials to use their routes. By the late Ming period, travel was further facilitated by the widespread availability of travel guides detailing trade routes.[97]

The restoration of the Grand Canal and the rise of coastal shipping were significant factors in the growth of trade during this time period.[24] Additionally, the development of the internal market was aided by the construction of bridges and roads in southern China and the Grand Canal area, which began in the late 15th century, and in northern China from the early 16th century. While bridges were initially built by both the state and private individuals during the early Ming period, the majority of new bridges in the middle Ming era were funded by merchant associations. Local officials often opted for cheaper pontoon bridges, but as the transportation network improved, these were gradually replaced by more durable stone bridges.[98]

In terms of transportation, there were notable differences between northern and southern China. In the north, land travel was the primary mode of transportation, while in the south, water travel was more prevalent. This was largely due to the presence of the Yangtze River, which provided a convenient and efficient means of transportation. Water transport on rivers and canals was not only faster, but also more cost-effective. Ships were able to carry much larger loads compared to land vehicles. For example, a common grain barge on the Grand Canal could hold up to 30 tons, while large river ships could carry up to 180 tons. In comparison, a light wheeled cart on good roads could only transport about 120 kg of cargo over a distance of 60 km, and a mule-drawn cart could carry up to 3 tons over a distance of 175 km. As a result, the cart was only used as a substitute for the lack of river transport.[99]

Market levels

Most of the population only had access to local markets, where they would exchange goods and services. Due to their knowledge of labor prices and expectations of fairness, there were limited opportunities for individuals to become wealthy in these markets.[100]

The second type of market was the urban market, which was primarily found in regions where landowners resided in cities (such as Jiangnan, where officials were the dominant class, and Fujian, where merchants were prevalent). In these markets, tenants and landowners would trade surpluses and rents. While goods were transported over longer distances, from the countryside to the cities, merchants were not typically involved in these transactions. The volume of goods sold in this manner was significant, totaling 30–40 million dan of grain.[101]

The third form of market that emerged during the Song period was the national, supra-regional market. This market facilitated long-distance trade of both surplus goods and products specifically grown or produced for sale. This supra-regional market eventually evolved into an international trade network by the mid-16th century, which was primarily organized and conducted by merchants seeking to profit from inter-regional price differences.[101] During the 15th century, a single national market began to emerge in Ming China as ties between provinces and regions strengthened.[24] The state regulated trade of certain goods such as tea and salt.[102] The majority of long-distance trade, about 42%, was in foodstuffs, with approximately 11% of the total food production. This mainly consisted of 10 million tons of grain, not including grain collected by the state as tax and distributed throughout the empire.[103] Following food, cotton fabrics made up 24% of long-distance trade (53% of their total production), while salt accounted for 15%, tea for 8%, silk fabrics for 4% (92% of their production),[85] and raw cotton and silk each made up 3%.[104] Other important traded goods included metals, metal products, and sugar.[24]

Long-distance trade routes and goods

rice,

cotton,

silk,

and trade directions:

rice,

cotton,

cotton fabrics,

silk.

The Yangtze River was the most crucial trade route and artisans would often use this route to purchase food in exchange for money. The most active trading occurred in Jiangnan, where there were numerous tax offices that collected trade taxes and fees. The Grand Canal was the second most important trade route. While the transportation of rice collected as taxes was not considered a commercial matter, other goods such as rice and cloth were also transported north in exchange for salt licenses. After 1420, luxury goods were also transported to Beijing, with ships returning with cotton and other products. Some of the major cities along the canal included Dezhou, Linqing, Gaoyou, and Yangzhou.[102] Granaries that collected tax rice for Beijing were located in Dezhou, Linqing, Huai'an, and Xuzhou. The sea also played a significant role in long-distance trade, with exports such as silk, ceramics, cotton fabrics, lacquerware, and sugar. During most of the Ming era, foreign trade outside of tributary relations was illegal, making it challenging to estimate its extent. The last significant area of commercial activity was a strip along the northern borders, where there was a high demand for goods from numerous military garrisons.[105]

The most significant product of long-distance trade was rice.[105] In the late 15th century, southeastern China, particularly the mountainous and densely populated Fujian Province, was not self-sufficient and relied on rice imports from Jiangnan, Guangdong, and Guangxi. Even the highly productive Jiangnan region began to struggle with self-sufficiency in the early 16th century, despite the high quality of its local rice. This was due to the high demand for rice in Jiangnan, driven by its dense population,[105] numerous large cities, and high taxes (as the state required local rice for its superior quality).[103] To meet this demand, merchants transported rice to Jiangnan via the Yangtze River from Huguang, Jiangxi, and Anhui.[105] After the mid-15th century, the government began selling salt licenses for silver instead of exchanging them for rice deliveries at the border. As a result, the government and/or soldiers purchased rice directly from the northern garrisons. Local production in the border regions was not sufficient and gradually declined, leading merchants to import food from the south.[103]

Cotton was the second most important commodity in long-distance trade.[103] It was primarily grown in Jiangnan, where it even surpassed rice as the main crop in some districts during the 16th century.[106] Other major cotton-producing regions included Hunan, Shandong, Jiangxi, and Huguang. While some cloth was produced locally, the majority of it was transported by shippers to Jiangnan and eventually to Fujian for processing. The main hub of cotton cloth production was the Jiangnan prefecture of Songjiang.[103] In the early years of the Ming dynasty, cotton cloth was primarily exported to the north and was also used in the exchange of cloth for horses along the border. By the end of the Ming era, textile industries were also emerging in the northeast, specifically in Beizhili and Shandong. As a result, Jiangnan began to lose its markets in the northern and western regions. The total cotton production, including local production, was estimated to be around 20 million bushels, with a value of 3.3 million liang.[107]

The third most important commodity in the market was silk, which was produced in the countryside and processed in cities. For example, silk from Huzhou in northern Zhejiang was processed in cities such as Hangzhou, Huzhou, and Suzhou. Similarly, silk from Baoning Prefecture (present-day Langzhong) in Sichuan was imported by merchants to workshops in Lu'an, Shanxi, where cloth production continued even after silk production in the surrounding countryside had ceased. During the late Ming period, silk fabrics for the foreign market were woven by factories in Fujian and Guangdong,[107] using imported Huzhou silk.[73] The total production of silk was approximately 300,000 skeins, valued at 300,000 liang.[107]

Other products, such as sugar, paper, iron, and copper, were also traded, but in lesser quantities. For example, sugar was shipped from Changzhou and Quanzhou in Fujian to regions such as Jiangnan and Zhejiang. Paper from Yanshan in Jiangxi was transported to Henan and Anhui. Iron was traded from Guangdong to Jiangxi, from Sichuan to Wuxi in Jiangsu, and from Fujian to Suzhou. Foshan in Guangdong was the most important center for the production of iron tools and products.[107] Copper from mines in Huguang, Guizhou, and Yunnan was shipped to Wuhu on the lower Yangtze River, a major hub for the metal trade.[108] Additionally, the trade of fertilizers began.[107]

Foreign trade

Early Ming government policies, organization, and territories of trade

The Hongwu Emperor held a belief that foreign countries were impoverished, inferior, and uninteresting. As a result, he rejected the idea of conquest and instead chose to focus on defending the empire. He also viewed foreign goods as unnecessary. Foreign countries, however, were highly interested in trading with China. This created significant business opportunities, but the early Ming government's values did not align with the concept of free trade "as equals". To address this issue, the Hongwu Emperor implemented a tribute system, banning private trade and replacing it with state-organized offices. These offices included the mashi (馬市) for horse trade in the north, the chamashi (茶馬市) for exchanging horses for tea in the west, and the shibo (市舶) for maritime trade along the coast.[109] Merchants were required to navigate a complex process to obtain permits and official approval for the volume and types of goods they could trade.[110]

Offices for the exchange of horses for tea (the offices in Ganzhou, Minzhou, and Huanglang existed only briefly),

Maritime Trade Offices,

and the most important imported goods.Preventive measures were implemented to combat smuggling. For example, on the western border, individuals were only allowed to possess a maximum of one month's supply of tea. In the northwestern province of Shanxi, tea consumption was completely prohibited. Those who violated these prohibitions, regardless of their social status, were often executed. An exception was made only for the husband of Princess Anqing, daughter of the Hongwu Emperor, who was caught smuggling and was allowed to commit suicide instead of facing execution.[110]

The Ming government also tightly regulated private maritime trade with foreign countries, as evident in the name of their state policy: Haijin, meaning "sea ban". Trade with Japan was limited to the port of Ningbo, while trade with the Philippines was conducted in Fuzhou and trade with Indonesia in Guangzhou. Specifically, the Japanese were only permitted to sail to Ningbo once every ten years, with a maximum of three hundred people on two ships. These strict regulations ultimately led to a rise in illegal trade between Chinese merchants and foreign countries.[35]

The restrictions on trade and the prohibition of private foreign trade were supported by the conservative landowners who held the most political power during the early Ming dynasty.[111] They believed that China's control over foreign powers was not dependent on military or economic strength, but rather on moral superiority. This belief led them to reject free trade and instead promote an exchange of tribute for gifts. Free economic activity was seen as a threat to the balance of the economy and society, as it could lead to social polarization and disrupt the self-sufficient and egalitarian society of China. The specific attitude towards overseas trade varied depending on the current foreign policy and socio-political situation.[111]

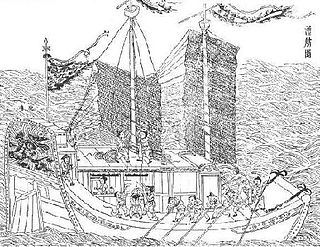

Despite strict state regulations, Ming China was heavily involved in international trade, exporting Chinese products to markets in Southeast Asia, Japan, Europe, Dzungaria, and Kashgar. One notable example of this was Zheng He's seven state expeditions to Indonesia, India, and East Africa. However, private influence often prevailed in the trade industry, as was the case in other areas of the economy.[24] Chinese products were in high demand on the international market, allowing for large profits to be made. For example, while 500 grams of raw silk cost only 5–6 liang in China, it could be sold for ten times that amount in Japan. Similarly, the price difference for horses from Mongolia was three times higher, and the price of Sapan wood, used for making red dye and imported from Japan, was fifty times higher in China.[112] China's main exports included silk, porcelain, cotton fabrics, metal products, ceramics, lacquerware, tea, and sugar. On the other hand, raw materials such as pearls, precious and semi-precious stones, ivory, rare woods, and medicines were imported from the south, while horses, furs, and ginseng were imported from the north. Maritime trade, primarily conducted by Chinese merchants, experienced significant growth.[24]

Foreign trade in the 16th century, the arrival of Europeans

In the late 15th century, the Ming government adopted an isolationist policy.[113] In the early 16th century, Portuguese navigators appeared in the Indian Ocean and soon in the seas of Southeast Asia. Their plundering and pillaging in the region paralyzed maritime trade and caused an economic crisis from which Southeast Asia did not recover until the 1530s.[114]

From the mid-1520s, foreign maritime trade was again suppressed by the government (but not coastal internal trade, which remained fully legal).[115] Shipbuilding laws were passed, limiting the size of vessels, but the weakening of the Ming navy also led to the activation of pirates in Chinese coastal waters.[116] Pirates, known as wokou (literally "Japanese bandits"),[c] raided both merchant ships and coastal towns and villages.[116] Despite their name, the wo-khou were primarily Chinese, with some Japanese and European adventurers joining their ranks. They often received support from local gentry, who were enticed by the potential profits from illegal trading activities.[117]

The policy of banning private foreign maritime trade was in effect until 1567, when it was officially lifted,[113] although restrictions on trade with Japan continued. The Portuguese initially acted as intermediaries between China and Japan, buying Chinese silk and selling it in Japan at inflated prices. They used the profits to repurchase silk.[118] By 1573, the Spanish had established themselves in Manila and, with their financial power fueled by silver from American mines, they pushed the Portuguese into the background.[119][120]

China's main exports to the world were porcelain and silk. The Dutch East India Company alone shipped around 6 million pieces of porcelain to European markets between 1602 and 1608.[121] The list of goods imported from China by the Filipino Spaniards was extensive, as seen in the notes of Antonio de Morga (1559–1636), a Spanish official in Manila.[122] American historian Patricia Ebrey highlights the significance and scale of the trade by listing the quantities of silk sold to European buyers.[35]

In one case a galleon to the Spanish territories in the New World carried over 50,000 pairs of silk stocking. In return China imported mostly silver from Peruvian and Mexican mines, transported via Manila. Chinese merchants were active in these trading ventures, and many emigrated to such place as the Philippines and Borneo to take advantage of the new commercial opportunities.

Accounting

A sophisticated system of accounting, known as sizhu jiesuan (four-pillar accounting system), has been utilized in China since the Tang dynasty to record economic activities. It was later adopted as the standard accounting procedure for government offices during the Song dynasty.[123] As business, trade, and banking flourished in Ming China, merchants and businessmen began to realize the limitations of existing accounting methods. As a result, a combination of double-entry and single-entry accounting, known as sanjiao zhang (three-leg bookkeeping), was introduced in the mid-15th century.[124] Under this system, accountants used double-entry bookkeeping for receivables and transfers, while cash payments were recorded in a single entry. In the late Ming period (Wanli to Chongzhen eras, c. 1570 – c. 1640), a more refined system known as longmen zhang, or "dragon-gate bookkeeping", emerged among bankers and eventually spread to the commercial and manufacturing sectors.[125] This system involved a strict classification of accounting operations into income, expenditure, receivables, and payables, and utilized double-entry bookkeeping for all transactions. However, that simple accounting methods were still prevalent, particularly among small businesses.[126]

Remove ads

Taxes and finance

Summarize

Perspective

State financial administration

Ministries of Revenue, War and Works

The highest financial authority in the Ming dynasty was the Ministry of Revenue, but their role was limited to monitoring the delivery of food, materials, and goods collected from the population to designated locations.[127] The ministry did not have the responsibility of creating a budget. Instead, tax revenues were directly allocated and delivered to the offices and organizations that consumed them. This resulted in a complex system of bills and receipts, rather than a centralized budget.[128] Any non-routine expenditures had to be approved by the emperor, and the source of funding was also determined by him.[129]

In addition to the Ministry of Revenue, the Ministry of War also played a role in collecting taxes as during the Hongwu era, land taxes were reduced by half in some regions of the four provinces in exchange for selected households raising horses for the army. This practice was later abolished and replaced with a regular tax levy, but the income still went to the Ministry of War.[130] The ministry also collected taxes from soldier-peasants, who were former soldiers demobilized after the wars that established the Ming dynasty, and their descendants. These soldiers were allocated one-tenth of the state's agricultural land,[131] and the income from their farming was used to feed the army.

The Ministry of Works was responsible for ensuring the requisitioning of materials and the fulfillment of labor obligations.[130] Skilled labor was assigned to artisan households, while unskilled labor was assigned to peasants. As labor obligations were gradually replaced by cash payments, the ministry received significant income in silver. This silver was then deposited into the Chengyin Treasury.[132][d]

Regional units, local government

The administrative system was divided into four tiers: province, prefecture, sub-prefecture, and county. In some cases, a unit may have been omitted, resulting in a three-tiered system. The primary responsibility of counties was to collect taxes, while prefectures assessed and distributed them. Provinces then forwarded the taxes to higher levels of government.[132] In larger or remote prefectures, sub-prefectures served as an intermediate level between prefectures and counties, or as small prefectures within provinces.[129]

However, with the exception of certain special revenues (salt, internal and external customs duties, timber levies, etc.), all taxes were ultimately collected by the county office. The prefect's duties included supervising counties, managing state granaries, overseeing the postal service, and collecting commercial taxes. If the prefecture contained mines, pastures, or state plantations, the prefect was also responsible for managing them. The prefect could adjust the distribution of taxes between counties by changing surcharges and conversions.[133] In later periods, regional officials had more flexibility in revising and adjusting the tax structure, as long as it did not interfere with the duties of other offices. They risked facing criticism from censors or non-cooperation from the gentry if their changes were unsuccessful. If successful, these changes would become permanent.[133]

For tax purposes, county offices compiled population censuses known as the Yellow Registers, while land was recorded in the Fish-Scale Map Registers.[38] These censuses were regularly updated by the county offices, which were the lowest level of state administration. Additionally, three copies of the censuses were filed with higher authorities, up to the Ministry of Revenue.[38]

The population was divided into groups of 110 households, known as li, which were further divided into ten groups of jia, each consisting of ten households. The remaining ten wealthiest families took turns leading the hundred households for a year.[134] Each year, one jia was responsible for providing services and supplies, under the leadership of the li leader. After ten years, a new census was taken and recorded in the Yellow Registers, and the households were redistributed into li, starting a new cycle.[135]

Corvée labor and levies

In the first century of the Ming dynasty, the lijia served as the backbone of the state, providing all necessary materials and goods at their own expense. This included office equipment and repairs, fuel supplies, weapons and equipment for soldiers, and other essential items. The only exceptions were grain and some other products collected as land tax. In addition to these duties, members of the entrusted lijia also performed auxiliary work such as supervising prisons, escorting prisoners, and ensuring the operation of postal stations and equipment. They were also responsible for managing state warehouses and storehouses, locks, and supplying all state administration personnel, with the exception of about 8,000 senior officials.[135] The authorities did not have a set budget and instead drew all expenses and needs from subordinate li.[136] Services for the palace, supplies of materials and goods, and the work of craftsmen were divided into counties and li, and provided individually without any consolidation of accounts.[137]

Peasants were required to send one person for every 100 mu of land to work for one month on state buildings. Artisans, on the other hand, were expected to work in state workshops for three months every three years. Military families were also expected to contribute conscripts and food.[42] These obligations were based on the size of the household, with larger households having a greater number of able-bodied men and larger properties. Major construction and building work were often funded through extraordinary levies and requisitions, which were outside of the regular system. In addition to the lijia system, wealthy households were also responsible for collecting land taxes and delivering them to state warehouses as tax captains (liangzhang).[135]

Corvée services, both regular and extraordinary, were extremely burdensome, but certain groups, such as students in state schools, examination graduates, and officials, as well as their relatives, were exempt from these services, providing significant benefits for their families. Over time, the number of exemptions grew significantly, as the number of students in state schools increased from 35,820 during the Zhengde era (1506–1522) to 500,000 by the end of the Ming era. The number of former officials enjoying these privileges also increased tenfold.[138]

A reform was implemented locally in 1443 and was eventually adopted throughout the empire by 1488.[136] Under this reform, the jia served twice in a ten-year cycle—once as a supplier of materials and goods, and the second time as a provider of services and labor. As the 16th century progressed, the use of labor and materials gradually shifted to payments in silver, often in the form of a surcharge on the land tax, but a portion of these payments remained tied to the number of able-bodied men in a household. Despite these reforms, the conversion to silver was not fully completed by the end of the dynasty, and the work obligation was still partially in place.[139] In the southern regions, approximately 70% of the work obligation was transformed into surcharges on the land tax, while in the northern regions, this number was closer to 50%. Overall, about 5 million liang of silver were collected from these surcharges on the land tax, which was equivalent to roughly 21 million liang of silver.[140]

In order to fairly distribute taxes among taxpayers, various calculations and adjustments were made at the county level. Some areas used a 40% calculation based on the number of adult men and 60% based on the size of the fields, while others converted the fields into "fiscal men" or, conversely, converted men into "fiscal mu".[141]

Land tax