Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Narcís Oller

Catalan writer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Narcís Oller i de Moragas (Catalan pronunciation: [nəɾˈsiz uˈʎe]; 10 August 1846 – 26 July 1930) was a Catalan lawyer and novelist who initially wrote in the traditions of literary realism and naturalism[disambiguation needed], later adapting his style to the Modernisme movement, the Catalan equivalent of Art Nouveau. Despite his stylistic evolution, he is considered one of the leading Catalan authors of the 19th century.[1][2][3]

He is best known for his novels La papallona (The Butterfly), which featured a foreword by Émile Zola in the French translation; L'Escanyapobres (The Usurer), regarded as his masterpiece; and La febre d'or (Gold Fever), set in Barcelona during the speculative real estate boom known as promoterism. His novel La bogeria (The Madness) was translated into English by Douglas Suttle and published by Fum d'Estampa Press in 2020.[4]

Oller also translated works by Leo Tolstoy and Alexandre Dumas, père into Catalan.[5]

His contribution was instrumental in the Catalan literary renaissance known as the Renaixença, and he helped pioneer a modern Catalan prose style.[6]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Narcís Oller was the son of Josep Oller i Yxart (1820–1848)[7] and Rosa Moragas i Tavern (1821–1876).[8] He was orphaned of his father at the age of two and went to live with his mother in the ancestral Moragas house in Valls, where he was educated in a wealthy, enlightened, and liberal environment. He studied law in Barcelona, graduating in 1871. He first worked as a civil servant in the Diputació de Barcelona and later set up practice as a procurator. He remained in this profession almost until his death.[9]

There are few remarkable events in Oller's life—he himself used to say that he lived "like a simple bureaucrat"—and biographical facts had little influence on his literary production. Oller was a moderate liberal, politically close to conservative Catalanism, and socially embedded in the bourgeois class, the world of which he portrayed in detail in his narratives.[10]

Oller began writing at a young age; his early works, written in Spanish, are almost all lost or unpublished. Around 1877 he decided to switch to Catalan: “I finally saw clearly,” he wrote in his Memòries literàries, recalling this period, “that between the writer and his native language there is a bond so strong that it has no possible substitute.”[11]

Several factors influenced this decision, including the impact of the Jocs Florals of that year (when Jacint Verdaguer’s L'Atlàntida was awarded and Àngel Guimerà was named mestre en Gai Saber) and his participation in literary gatherings, especially the circle around the magazine La Renaixença. He embraced Catalan not only for sentimental or political reasons but also for strictly literary ones. By the late 1870s he was reading Émile Zola and other contemporary French authors, discovering realism, which in Spanish was already cultivated by writers like Juan Valera and Benito Pérez Galdós. His close friends, the critics Josep Yxart (who was also his cousin) and Joan Sardà i Lloret, persuaded him of the potential of realist and naturalist fiction and encouraged him to adopt these models, which were dominant in Europe at the time.[12] Once converted to realism, Oller saw no other way to reflect his environment faithfully than through the language of the world he depicted—Catalan. This attitude, both in theory and practice, was a constant in his literary career.[11]

Oller enjoyed great respect and esteem among contemporary Spanish authors such as Galdós, Pereda, and Valera, with whom he maintained frequent relations. They often urged him to write in Spanish, citing reasons of fame and fortune. Oller, however, fully aware of what writing in Catalan entailed, never agreed.[9]

In 1886 a polemic broke out in the Spanish press about the use of Catalan as a literary language, curiously concerning only prose. Galdós, for example, wrote:

I understand that the resuscitators of literary Catalan may achieve their aim in poetry, because poetry lives perfectly in ingenuous and uncultivated languages, almost better than in very elaborate ones; but to attempt in Catalan the contemporary novel, which requires an extremely rich and flexible diction, seems absurd to me, with due respect to the distinguished Oller.

These statements echoed what Galdós had already written to Oller in private letters a couple of years earlier, including the blunt remark: “es tontísimo que V. escriba en catalán” (“it is very foolish for you to write in Catalan”). Oller replied on 14 December 1884 with a letter that amounts to a declaration of principles about his concept of realism:

I write novels in Catalan because I live in Catalonia, I copy Catalan customs and landscapes, and Catalan are the characters I portray. I hear Catalan every day, at all times, as you know we speak here. You cannot imagine a more false and ridiculous effect than what I would feel making them speak in another language, nor can I express the difficulty I would face in trying to find in the Spanish palette, when painting, the colors that are familiar to me in Catalan […]. Do you not believe that language is a concretion of the spirit? Then how can it be divorced from that fusion of reality and observation that exists in every realist work?

Remove ads

Novels

Summarize

Perspective

Within Ollerian narrative, three stages can be distinguished:

Apprenticeship

At the end of the sixties, Oller had begun to collaborate in the press in Spanish, often using pseudonyms; around 1872 he started a novel, also in Spanish, which he did not finish. Around 1874 he began to consider writing in Catalan and between 1877 and 1878, as we have already seen, he finally chose to write in his language. Thus in 1879 he published the collection of stories Croquis del natural, which was received by critics as a turning point in Catalan narrative of the moment; that same year he won a narrative prize at the Jocs Florals with Sor Sanxa, a prize he won again the following year with Isabel de Galceran.

This first stage, of learning and formation, is characterized by the author's permanence within romantic and costumbrist coordinates, although the influence of realism begins to be detected, especially in La papallona (1882), his first novel and the one that closes this first phase of his production. Transitional work, it is still very much tied to romantic schemes. Thus, the plot — a feuilleton — is based on the story of a girl, Toneta, orphaned, poor, naive, illiterate, and sickly, who is seduced and abandoned by a papallona (womanizer), Lluís, from a higher social class. The action unfolds in twenty chapters and is set in Barcelona, a working-class Barcelona in which the first symptoms of the profound changes brought by industrialization begin to manifest. The life of the city, however, remains very much linked to costumbrist schemes.

The presence of lurid elements, chance, and a moralistic and implausible ending (at the gates of death, Toneta manages to marry the seducer) are elements that reveal the romantic legacy of the novel. However, aspects belonging to the realist line appear, ranging from the accuracy of dialogues and descriptions to the explanation of the biological and psychological background of the protagonist.

The novel achieved great critical and public success and was soon translated into several languages (French, Russian, Spanish...). Presented by some critics as the first example of naturalism[disambiguation needed] in Catalonia, Émile Zola, the theoretician of the movement, remarked in the preface of the French edition of the book that there were notable differences between Oller and this movement:

I have read that it comes from us, the French naturalists. For the setting, for the composition of the scenes, for the way of fixing the characters in an environment, yes: but for the soul of the works, for the conception of life, no, by no means. We are positivists and determinists, at least we do not intend to attempt more than experiences on man; and Oller, above all, is a narrator who is moved by his narration, who goes to the depth of understanding, at the risk of departing from truth.

Situated between Romanticism and Naturalism, La Papallona meant a significant change within Catalan novelistic: the overcoming of outdated literary schemes and the incorporation of our novel into the realist and naturalist line then predominant in Europe.

Consolidation

The first edition of the novel La papallona was published with a prologue by Émile Zola; the great public response it received gave Oller greater confidence as a narrator and in the literary model he had begun to follow. Thus, between 1883 and 1889, the author's most creative period took place: four novels and several collections of short stories.

In 1883, he published the tales Notes de color and later the novella L'Escanyapobres. The subtitle Study of a Passion, appearing in the first edition of this novel, already indicates a scientific and psychological intention. Set in an imaginary town—Pratbell—undergoing industrialization, it narrates the story of a couple of misers—Oleguer, the Escanyapobres, and his wife Tuies—whose passion for money leads them to isolate themselves and to the tragic death of the protagonist. Greed is viewed not only as a moral flaw (Oleguer's death, caused by his obsession with money, is clearly a "punishment") but also as a socially regressive attitude, since it hinders progress and productive investment that enabled the socio-economic transformation of Catalonia at that time.[14]

L'Escanyapobres is one of Narcís Oller's best creations. Here, more than in any of his other novels, imagination plays a very prominent role. On the other hand, it is the work in which sentimentality—always present in Oller—is least important, thanks especially to the use of two narrative techniques: irony and distancing. The latter is evident in the caricaturing—which some critics have described as grotesque—of characters and situations.[14]

Vilaniu (1885) was created from the narrative Isabel de Galceran, responding to pressure from some friendly critics. The action takes place in a small provincial town, Vilaniu (a symbolic name that fictionalizes the author's native town: Valls), where the infatuation of a young lawyer for Isabel, the wife of the local boss Galceran, triggers slander, which ultimately causes the misfortune of her family. The plot includes many elements of the social and political life of the historical moment: the "decline" of small rural towns, the struggles between liberals and moderates... The novel, which today seems one of the least interesting of the author's works, represents a certain technical regression compared to L'Escanyapobres. Ambitiously conceived, it failed to develop a romantic theme based on realist and naturalist schemes.[15]

La febre d'or is the longest of Oller's novels and undoubtedly the most notable as a historical source about an important stage in the country's evolution. In 1890, he published the first volume, written the previous year "in one rush", as he said himself. The plan for the work had been prepared for some time, but the news of the imminent publication of the novel L'argent, by Zola, on a similar topic, forced him to hasten its writing and edition. The second volume appeared the same year as the first, and the third in 1892. These circumstances surely contributed to many defects that prevented this novel, one of the author's best, from becoming a fully successful work.[16]

The theme idea comes from the stock market fever of 1880–1881. Oller confessed that he wanted to "closely study the history and character of that madness".[16]

Thus, in the story of Gil Foix and his family, he symbolically exemplifies those historical events.

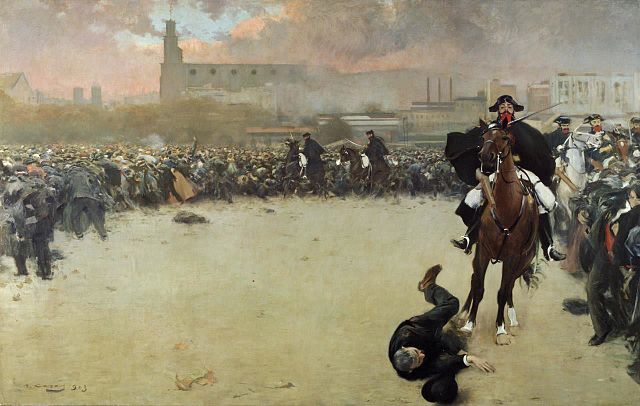

The novel is divided into two parts, with very significant titles: La pujada ("The Rise") (the first twenty chapters) and L'estimbada ("The Fall") (the last fourteen). Oller narrates the rapid economic and social ascent of Gil Foix from the petty bourgeoisie to the upper bourgeoisie thanks to his skillful stock market speculations. La febre d'or is both the story of particular characters and the story of an entire era of Barcelona. Oller portrays the transformation of an industrial and cosmopolitan city, framed between the stock market fever of the early 1880s and the 1888 Universal Exposition. This was, in Oller's words, a "titanic effort that showed so well our hidden energies and our thirst for progress, which ignited my imagination, my Catalanism, and my faith placed in this people".[17]

La bogeria (1899), based on a real event (the death of one of his clients), is a study of a psychological phenomenon—madness[disambiguation needed]—its possible causes without reaching any conclusion, and its social consequences. The action takes place between the September Revolution of 1868 and the early years of the Bourbon Restoration, and more specifically during the years of the gold fever. The spatial setting is mainly between Barcelona and Vilaniu.

The protagonist, Daniel Serrallonga, is an impetuous young man, an enthusiastic supporter of General Prim, a stock market player, and a litigant obsessed with his family, who slowly goes mad. Technically, the work marks a break with naturalist procedures. Indeed, instead of an omniscient third-person narration, there is a first-person narrator—a witness narrator who plays a secondary but prominent role in the action—and description loses prominence in favor of narration and dialogue. Thematically, however, it is the author's most naturalist novel, since the Zola-influenced theoretical principles of environmental and hereditary determinism are the core of the discussion about Serrallonga's illness.[18]

This novel closes Narcís Oller's most creative period. The works from this period are framed within the realist line from Honoré de Balzac to Émile Zola and aim, overall, to reproduce the reality of the time and country in which the author lived: the Catalonia of the Restoration. The perspective is clearly that of an observer belonging to the ruling social class, and therefore the most remarkable aspect is his examination of the attitudes and ideology of the bourgeoisie. The totalizing will is confirmed by some of his literary procedures, especially the reappearance of characters across different works and the limitation of the geographic space basically to Barcelona and the archetypal town of Vilaniu.[19]

Pilar Prim

When Oller wrote La bogeria (1899), Naturalism was already in decline across Europe, and in Catalonia Modernisme (Catalan Modernism) was emerging strongly as a new literary current. He had also lost his literary mentors, critics Yxart and Sardà, which left him creatively unsettled. These losses, along with evolving aesthetic demands, pushed him toward introspective themes and psychological complexity.[20][21]

It is therefore not surprising that Oller took four or five years before publishing his next novel, Pilar Prim (1906). In this work he decisively diverges from Naturalist conventions, striving to align with new aesthetic ideals. Thematically, the novel shifts from emerging bourgeois society to the established bourgeoisie of Barcelona, focusing on a widow bound by a marital clause that deprives her of the property's usufruct unless she remains unmarried.[20][21]

Technically, Oller returns to third-person narration (abandoned in La bogeria) and emphasizes descriptive passages in the first part of the novel—mirroring his Realist‑Naturalist training—but he transcends the old style through symbolic and psychological depth.[20][21]

Pilar Prim narrates the intimate story of a young widow who, constrained by social conventions—family pressure, moral prejudice, and legal impediments—struggles to follow her emotional desires. The novel incorporates Modernist features such as symbolic naming (the protagonist's name), landscape–mood correlations, indirect interior monologue, and references to Richard Wagner and Friedrich Nietzsche.[21][20]

After Pilar Prim, Oller ceased novel writing. Feeling marginalized by changing literary tastes, his literary output declined. He continued with translations (notably Madame X by Alexandre Bisson), published short stories and plays, wrote his Memoirs, and prepared his Complete Works edition.[22]

Short fiction and other genres

Oller's short fiction, both in quantity and in the diversity of forms and themes, represents an important part of his work, following broadly the same evolution as his novels. His production in this field comprises six volumes, which gather almost all his short stories and novellas, some of which had first appeared in periodicals before being collected in book form. His earliest collection, Croquis del natural (1879), already shows Realist tendencies, though Romantic and costumbrista elements still predominate.[23] During his most productive period he published Notes de color (1883), De tots els colors (1888) and Figura i paisatge (1897),[24] titles whose very names highlight the importance Oller placed on descriptive and pictorial elements. Later, after he had abandoned novel writing and most other literary activity, he returned to short fiction with Rurals i urbanes (1916) and Al llapis i a la ploma (1918). From 1923 he also contributed several short works to the collection La Novel·la d’Ara.[25]

According to Alan Yates, within the history of the Catalan short story, Oller's importance is comparable to his role as the founder of the Catalan novel.[26] Although guided by a moralizing impulse and a deliberate search for entertainment, his stories display a wide thematic range. Some are early versions of narratives later expanded into novels, such as Un estudiant, which reappears in La papallona, or Isabel de Galceran, which anticipates themes from Vilaniu. Others—Viva Espanya!, Natura, Angoixa—explore aesthetic paths that depart from strict realism, suggesting an openness to fantasy, mystery, and the unreal, although Oller usually returned to realistic closure, as critic Antònia Tayadella i Oller has emphasized.[27]

Stylistically, humor predominates in Oller's short fiction—often linked with satire, caricature, or the grotesque—relying especially on antithesis and irony. Taken as a whole, his short stories form a corpus of considerable literary quality that clarifies many of the defining elements of his fiction.[20]

Oller's dramatic works, by contrast, are limited and of little significance: Teatre d’aficionats (1900), containing short comedies and monologues (largely adaptations of foreign authors), and Renyines d’enamorats (1926), which includes a two‑act play adapted from Molière's Le dépit amoureux, three monologues, and La brusa, a brief parody of Maeterlinck's La intruse.[28]

Of far greater interest are his literary memoirs, Memòries literàries (subtitled Història dels meus llibres), published posthumously in 1962. For unknown reasons, they omit an entire chapter on Catalan theatre from Modernisme to the First World War. Written in the form of letters to Víctor Català between 1913 and 1918 (with additions up to 1922), they cover his literary life from the 1870s to 1906. The Memoirs stand out for their narrative force and vividness, even if the wealth of detail sometimes makes the prose heavy.[29]

They are also an extraordinary documentary source on Oller's creative process, the critical reception of his work, his relations with the literary milieu (including rivalries, resentments, and his rupture with younger writers), his contacts with Catalan and Spanish critics and authors, and, more broadly, on the workings of the literary and publishing world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[30]

Remove ads

Realist Oller

Summarize

Perspective

With the shift from Romanticism to Naturalism, Narcís Oller began writing in Catalan, justifying this change due to the impact of the Jocs Florals of Barcelona in 1887, where he discovered the strong link between writer and language; from 1878 onwards he started to experiment with Catalan, compiling a collection of various short stories by 1879. Realist Oller emerged from a combination of factors, his readings focusing on French realist novelists (from Honoré de Balzac to Émile Zola) and Spanish literature, becoming a supporter of progress. Thanks to Josep Riera i Bertrana, Oller not only connected with Àngel Guimerà but was also led to consider writing in Catalan.[31]

Zola said to Oller: "you are not a naturalist, although you know how to place characters within their environment, then you soften your story until you depart from reality." Oller found inspiration in the naked contemplation of reality, yet also aimed to discover its poetics. He used the same working method as the realists; in the genesis of La febre d'or (the novel with the most notes), he drew directly from reality, capturing it, for example, in the stock market. Oller chose characters according to their belonging to his contemporary society, such as Sor Sanxa, which he presented at the Jocs Florals. Oller was idealistic in the 1880s but, influenced by French and Spanish critics and writers, leaned towards realism.[32]

With La papallona, published in 1882 with a foreword by Zola Oller made a European leap to the level of José Maria de Eça de Queirós or Leo Tolstoy in their respective national literatures. Thanks to the foreword, Oller gained international fame and had the standing to be friends with novelists like Zola, Benito Pérez Galdós, José María de Pereda, or Pawlowski. The foreword contains important ideas: Barcelona is described objectively, but the characters are idealized—not in the conception of life—since French naturalists were positivists and determinists concerning human beings. In the French translation's foreword of La papallona, it is said to be the most read but not the best. In 1886, Oller wrote a letter to Zola about reading Germinal, at which point he adopted naturalist-realist parameters; that same year, he traveled to Paris with Zola.[33]

He never labeled himself a naturalist, but Valentí Almirall and Navarro Aliguer reported that Oller introduced naturalism in Croquis al natural (1879), reflecting the transition from Romanticism to Realism. Oller defined "naturalist" as synonymous with realist, i.e., a school based on observation of nature. Oller's work would not be what it is without naturalism, but it cannot be analyzed strictly from an orthodox naturalist perspective. His first contact with Zola as a reader was in the 1870s with the novel Une page d'amour, situated between L'Assommoir and Nana, a sentimental interlude that does not align with the harsher traits of the series... although he read Nana even if he could not admit it.[34]

In his correspondence, Oller wrote his opinion about Galdós's Lo prohibido, realistic portraits; about Galdós's Fortunata y Jacinta, he said they were essentially real and lively, full of life and truth, which he sought to achieve in his novels. Oller's geographic documentation was accurate; Yxart and Oller believed reality can only become reality through the artist's personality, meaning Oller was a naturalist as long as the viewpoint was softened.[35]

When Oller described the Catalan realist painter Galofre, he was in fact describing himself: "a variety of natural beauties of living reality, in love with living reality but also moving." Reflecting on the story La bufetada published in 1884, he said it was inspired by a real case (true, though the character was not a butcher but a master builder). He claimed he had to push reality towards plausibility, to align literary technique with reality. This theorization regarding language in 1877 led to an exchange of letters in which Galdós told him to write in Spanish to sell more books, and Oller replied that if he wanted to sell more, he would write in French.[34]

In his creative work, Oller employed techniques, motifs, and situations from the naturalist novel; he did not need to read naturalist theoretical texts because he was a great reader of naturalist-realist novels, hence the leitmotifs of the realist novel. When writing novels, Oller had reality as his starting point but was also saturated by the quantity of realist novels read, which he assimilated. His peak was in 1892, though a brief one; creatively, this was when he had the most confidence in the naturalist-realist model.[35]

In 1903, Oller published the article Pèl i ploma where he valued Zola's foreword; this assessment was influenced by the crisis of naturalism itself. In the mid-1890s, Oller experienced artistic disorientation leading to silence (except for a final novel in 1898) due to the deaths of his pillars Yxart and Sardà; without them, he felt helpless, also because of the changing literary context. The naturalist-realist model was in crisis, and Oller tried to resolve it with La bogeria and Pilar Prim but failed. He explained his fascination with Tolstoy's War and Peace, reflecting on the length, structure, and composition of the realist novel, thoughts triggered as the realist novel fell into crisis. One reason was the impact of psychological novel techniques from Russian literature. With the rise of Noucentisme, Oller disappeared from public life, but by 1925 it was recognized that the psychological and urban novel models were connected with Oller, specifically with Pilar Prim.[34]

Remove ads

Characteristics of Oller's Work

Summarize

Perspective

Maurici Serrahima, in studying Narcís Oller's work, highlighted that the novelist's overall literary purpose was "truth in art," that is, "the search for and reproduction of reality."[36] According to the aesthetic principles he followed, this reality had to be necessarily that of his country in the period he lived in. This is reflected in the themes he treats in his work, which collectively serve as a general chronicle of the transformation of Catalan society during the second half of the 19th century and the impact of the changes on both urban and rural life.

It is therefore not surprising that throughout his production appear those aspects that, for him, were the most significant of the rapidly developing world in which he was immersed: the construction of the railway, stock market games, the provincialism of small towns, caciquism, political struggles, revolutionary events, the rise of the bourgeoisie, the social and economic crisis of the countryside, and especially the growth of the large city, Barcelona.

Oller had a notable totalizing ambition when reproducing the reality of his time. It is thus curious to note that some of the most important phenomena of industrialization, such as the emergence of the proletariat and class struggle, are almost unnoticed in his work. Workers and their world appear very little in his literature, and even then from a perspective that does not go beyond a traditional and customary view.

Oller's work is often praised for its vivid realism and detailed depiction of Barcelona and other settings. His ability to create immersive and tangible environments is considered one of his major literary strengths.

The characters, however, are sometimes described as “slightly idealized.” Oller often emphasizes those aspects of the characters that are more idealizable—in the case of positive characters—or more caricatured—in the case of negative ones. Among his gallery of literary figures, the female characters tend to be the most fully developed psychologically; the male characters often have a more schematic character and a less rich and nuanced personality. Nevertheless, characters such as Daniel Serrallonga from *La bogeria* or Oleguer from *L'Escanyapobres* stand out as remarkable creations.

Oller's idealistic inclination in character portrayal relates to a broader aspect that Sergi Beser i Ortí, in a key study of the novelist's work, called "the narrative limitations of Narcís Oller."[37] These limitations depend largely “on two innate tendencies in Oller that belong to his most intimate personality and are reflected in his narrative reproduction”: moralism and a sentimentality of romantic origin.

This pair of elements, which contrast with the naturalist realism he tried to follow, are constant throughout his work. For Oller, sentiment was the most important thing in humans, and to save it, he resorted to moral criticism of human behaviors. Hence, the critique of moral and social flaws (greed, slander, unjust conventions...) and the reward for the “good” (even if, as in the case of Toneta in *La papallona*, it is at the threshold of death) and destruction for the “bad.”

Oller's narrative is, according to Beser, “the result of the confrontation of two difficult cultural and literary worlds to unite: on the one hand, realism bordering on Zola-like naturalism; on the other, a moralizing sentimentality that seems to move towards traditional Romanticism. A critical evaluation of Oller's works shows the writer's failure in those stories that do not overcome this contradiction (*La papallona*, *Vilaniu*) and the quality of those that, for different reasons, manage to resolve it (*L'Escanyapobres*, *La bogeria*), relegate it to a secondary plane (*La febre d'or*), or find a justification for it within a new concept of the novel (*Pilar Prim*).”

Remove ads

Historical significance of Oller

Summarize

Perspective

When La papallona was published in 1882, novel-writing in Catalan was barely twenty years old. To find earlier examples of the genre, one would have to go back to the late 15th century, when Tirant lo Blanc and Curial e Güelfa were written (the manuscript of the latter, discovered in the 19th century, was first published in 1901). Thus, Oller had hardly any predecessors when he decided to cultivate the novel. Before him, only a small production of romantic, costumbrist, and serial novels formed the limited background available.[38] Moreover, these types of novels corresponded to outdated literary models, since across Europe a new kind of novelistic literature was emerging: the realist novel.

Narcís Oller was the writer who, overcoming these anachronisms, managed to situate Catalan novel-writing within the most advanced literary currents of his time. Oller is undoubtedly one of the most relevant Catalan novelists and, in the opinion of Sergi Beser,

holds an important place within the European narrative of the

19thcentury and, although he is not among the great masters —Balzac, Charles Dickens, Galdós, Tolstoi, Eça de Queirós…— he is not far behind them; moreover, he represents for Catalan culture what these authors represent for their respective national cultures.

To properly evaluate Oller's work, one must consider several factors that conditioned its realization. On one hand, those stemming from his personality: a permanent literary insecurity —partially overcome thanks to the advice and encouragement of his literary friends, especially critics Yxart and Sardà— and a certain indolence facilitated by the lack of professional dedication to literature, which sometimes prevented him from pushing forward literary projects and plunged him into periods of doubt or discouragement.[40]

On the other hand, there were two problems arising directly from the Catalan cultural context: the imperfection of the literary language (“impoverished by scant cultivation in recent centuries and at that time subjected to tensions between supporters of colloquial Catalan and defenders of an archaizing language”) and the lack of suitable models for realist narrative. Oller partly replaced the inexistence of an appropriate literary tradition with contemporary French and Spanish novelistic literature.[41]

This novelistic literature followed the aesthetic codes of naturalist realism, and Oller adhered to this current. However, it was a conditional adherence. He accepted the composition techniques of the work but rejected the deterministic and materialistic ideology and the purpose of denunciation and social change present in Zola's doctrine. Furthermore, as noted before, moralist sentimentality profoundly conditioned his literary realizations.[42]

With all its shortcomings and limitations, Oller made an enormous effort materialized in a work of high literary quality that largely filled the existing void in the novel field, recovering the lost Catalan novelistic tradition and enabling the work of the late 19th century narrators.[43]

Narcís Oller today holds an interest that is not merely historicist, an interest that goes beyond his role as the founder of the modern Catalan novel. Today, his best creations (L'Escanyapobres, La bogeria, Pilar Prim, and even his short stories) are reissued with unusual frequency in our literary market. Oller, even eighty years after the publication of his last novel, still connects, like all good narrators, with the public.[44]

Remove ads

Works

Fiction

- El pintor Rubio, 1876 (in Spanish, unpublished)

- Un viaje de placer, 1868 (under the pseudonym Plácido)

- Croquis del natural, 1879

- La papallona (The Butterfly), 1882 (with foreword by Émile Zola)

- Notes de color, 1883

- L'Escanyapobres, 1884

- La bufetada, 1884[45]

- Vilaniu, 1885

- De tots colors, 1888

- La febre d'or, 1890–1892

- Figura i paisatge, 1897

- La bogeria, 1898

- Pilar Prim, 1906

- Rurals i urbanes, 1914

- Al llapis i a la ploma, 1918

Theatre

- Teatre d'aficionats, 1900

- Renyines d'enamorats, 1926

Essays

- Memòries literàries. Història dels meus llibres (1913–1918, published 1962)

Remove ads

Further reading

- Shaw, Donald. Modern Catalan Literature. University of Wales Press, 1997.

- Pujol, Joan. “Narcís Oller and the Realist Novel.” Hispania, vol. 55, no. 3, 1972, pp. 480–487.

Literary heritage

Summarize

Perspective

Historical Archive of the City of Barcelona

The personal papers and the library of Narcís Oller were donated free of charge by Joan Oller i Rabassa to the Historical Archive of the City of Barcelona (AHCB) at the end of the Spanish Civil War.[46] An important addition was made on 18 October 1968, when the Archive purchased further documents, among which the original handwritten manuscript of Memòries literàries o històries dels meus llibres (Literary Memoirs or Stories of My Books) stands out. Although it had already been published in 1962 by Editorial Aedos in Barcelona, access to the manuscript remained restricted by explicit request of the family. The publication reproduces the manuscript almost in full, with some corrections, except for chapter XVI, which was omitted.[47]

Oller's personal collection, amounting to 5,973 documents, is one of the most important private holdings preserved at the AHCB. Especially significant is the correspondence, with 4,798 letters. The collection comprises: personal and family documents (345 items); copyright documents (35); professional activities (87); manuscripts (170); correspondence (4,798 letters); and press materials (527). A portion of these had already been classified earlier into nine series, registered under the initials NO and the corresponding Roman numeral of the series, followed by the document number—3,464 records in total.[46]

Centre for Studies: Narcís Oller Society

The Narcís Oller Society is a non-profit association founded by individuals linked to education (both university and secondary) and to cultural and publishing activities in Valls. Its objectives are to become a reference centre for the dissemination, promotion, and research of Oller's literary heritage; to encourage the study of Oller and modern narrative across Catalonia; and to publicize the author as one of the most relevant figures of nineteenth-century Catalan literature.[48]

The Society's main projects include the publication of Oller's complete works, the creation of literary routes, a signposted itinerary through his native city, a centre for interpretation and documentation, and the organization of symposia on narrative, especially in the Alt Camp region.[48]

Narcís Oller Literary Route

The Narcís Oller Society offers a literary route through the old town of Valls aimed at school groups (ESO and Baccalaureate) as well as tourists and visitors. The route, inaugurated in November 2008, allows participants to walk through the most significant places connected with Oller's life and works. Informative plaques and medallions mark the locations, and guides read selected fragments of Oller's writings.[49]

The guided tour covers eight emblematic sites in Valls, such as the Plaça del Quarter, the Carrer de la Cort, the Plaça del Blat, the Arcs de Ca Magrané, the Plaça del Carme, the Plaça de l'Oli, the Plaça dels Alls, and the El Pati (Valls). At each stop, relevant passages from works such as Vilaniu, La febre d'or (The Gold Rush), and La bogeria (Madness) are read aloud. The full route consists of 11 information points and is also available for self-guided visits using a leaflet provided by the Society.[50]

Literary map

Several key locations in Valls and Barcelona appear in Oller's works. In Valls, the house at Carrer de la Cort no. 25 is believed to be his birthplace, and nearby is the house of Daniel Serrallonga, the protagonist of La bogeria. In Vilaniu, the Montellà family residence is set at Plaça del Blat, overlooking the square where human tower festivals (castells) take place.[51]

Other significant sites include the Ortega family house in the nearby woods (which had belonged to Oller's father), frequently mentioned in Vilaniu and La bogeria; and the Moragas family summer house, called "Maiola" in Oller's writings, a neoclassical building from the early eighteenth century that became a retreat for the well-to-do families of Valls in the nineteenth century.[52] These locations are also linked with Oller's cousin and mentor Josep Yxart. Some of these settings were used in the film adaptation of La febre d'or.

In Barcelona, Oller placed scenes of La febre d'or at the Portal de la Pau, near today's Barceloneta district, and described the demolition of the sea wall and the opening of the city to the sea. He also set parts of La bogeria in the same area. Finally, the former convent of Santa Mònica (today the Arts Santa Mònica Centre) serves as the backdrop for the baptism scene in La papallona (The Butterfly).[53]

Remove ads

Further reading

- Casacuberta, Margarida. Narcís Oller: Realisme i naturalisme. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1996.

- Casacuberta, Margarida. "La novel·la catalana de la Restauració: Narcís Oller i el realisme europeu." In: Història de la literatura catalana. Part moderna, vol. 6. Barcelona: Ariel, 1986, pp. 115–144.

- Comas i Güell, Montserrat. "Narcís Oller, Víctor Balaguer i La febre d'or." Del Penedès, Winter 2005–2006. Available online at RACO.

- Història de la Literatura Catalana. Vol. 1. Col·leccionable del diari Avui. Barcelona: Edicions 62, pp. 309–319.

- Pujol, Joan. "Narcís Oller and the Realist Novel." Hispania, vol. 55, no. 3, 1972, pp. 480–487.

- Shaw, Donald. Modern Catalan Literature. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1997.

- Yates, Alan. Narcís Oller. Twayne's World Authors Series. Boston: Twayne, 1979.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads