Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Folding book manuscript

Type of manuscript From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Folding book manuscripts[a] are a category of manuscript in the leporello format, a long strip folded back and forth upon itself. Often contextualized as a compromise between the scroll and a bound codex, the folding-book manuscript developed independently in various regions and times across the world, but largely saw major use in Pacific Asia and Mesoamerica.

Remove ads

East Asia

Summarize

Perspective

Cyril James Humphries Davenport noted in his 1898 lecture that "writing upon a roll was found to be the most convenient at a very early date by the Chinese, Japanese and [K]oreans, they were also the first to find out that if the rolls were simply folded backwards and forwards between the 'pages' of writing or printing, the whole book became easier to read, and this form... is used in those countries to the present day."[1]

China

Chinese folding book manuscripts (Chinese: 經摺裝, pinyin: Jīngzhé zhuāng) originated in China during the Tang Dynasty (618 - 907), as an alternative to scrolls, making texts easier to handle and read. In particular, this form of binding was widely used for Buddhist scriptures, calligraphy, and illustrated works, originally in Sanskrit — hence an alternative name, 梵夹装, "Sanskrit-style binding".[citation needed] This format also spread to Japan and Korea with the importation of Buddhism.[2][3][4]

Before the invention of paper, texts were typically recorded in two main formats. The first format is one where texts were written on silk cloth and stored as scrolls—a format known as shoujuan (Chinese: 手卷, pinyin: Shǒujuàn, lit: "hand roll"). The other format is one where texts were inscribed on wooden materials, especially bamboo. These bamboo strips were cut into thin vertical slats and then laced or knotted together with cord, allowing them to be either rolled like a scroll or folded in a stacked, back-and-forth manner. This folded version was called jiandu (Chinese: 簡牘, pinyin: Jiǎndú) and dates back as early as the 5th century BCE.[5][6]

After the invention of paper in the second century CE, Chinese bookmakers began adapting the jiandu structure to the new medium. This innovation led to the development of the jingzhe zhuang binding style during the Tang Dynasty. The new format maintained the folded structure of jiandu but used paper instead of bamboo, making books lighter, more flexible, and easier to reproduce.[5][6] Jingzhe zhuang books consisted of long rolls consisting of sheets of paper pasted together began to be folded alternately one way and the other to produce an effect like a concertina.[7] At the same time, the Tang era was a period of significant development for Buddhism in China. During this time, a sinicized Buddhism was widely accepted and practiced throughout the empire, with many monasteries and temples, and the Tang Imperial Court commissioned the translation of many new Buddhist texts from Sanskrit to Chinese. As such, the accordion book binding became a popular format for printing Buddhist scripture.[8] One of the earliest surviving examples of a jingzhe zhuang book—a miniature version measuring 10 x 14 cm—was discovered at the Dunhuang archaeological site in western China. Dating to before 900 CE, it is the oldest known miniature accordion book, marking a significant step in the evolution of East Asian bookmaking.

Japan & Korea

As the Tang dynasty in China was highly influential in terms of technology and culture on its surrounding polities, particularly in Korea and Japan (known in Japan as Japanese: 折り本, rōmaji: Orihon), this style of binding eventually spread to those respective areas, where it was also similarly heavily associated with the printing of Buddhist sutras.[2][9] Besides Buddhist texts, the accordion book style of binding also eventually became used for other types of writing. For instance, one of the most popular books to appear in concertina format in 12th-century Japan was the Tale of Genji. The accordion book style of binding also subsequently further spread into other regions such as Tibet and the Western Xia during subsequent Chinese dynasties such as the Yuan and Ming dynasties.[10]

Remove ads

Ethiopia and Eritrea

Summarize

Perspective

The sensul (Amharic: ሰንሱል sənsul, lit. 'chain'[11][12]) or chained manuscript[13] is a pictorial folding book manuscript from Ethiopia and Eritrea. Regional codices predate sensul by centuries; sensul were created in the late fifteenth to early sixteenth century, and never overtook scrolls nor codices. Often depicting Ethiopian Christian art, Christian sensul were typically used as an aid to prayer or icons.[12] [13]

Sensuls as well as other Ethiopian codices were a prized trade good in Europe since the fifteenth century, with tourist trade continuing today. Manuscripts were also a target of art looting, such as during the 1898 British expedition to Abyssinia. Manuscript illustrations were often cut from the books for resale or for album collections; by the 1960s, English art dealers broke pictorial sensuls into individual folios instead, for framing. Outside of their context, disassembled sensul may be erroneously identified as typical codex folios, affecting the accuracy of museum curation and art history.[12]: 175–176

Remove ads

Europe

England

Ancient Rome

The Vindolanda tablets of Roman Britain (c. 100 CE) have been hypothesized as leporello-format books, wherein each folded wooden folio is tied to the next.[14]

Medieval

The vade mecum of medieval England was sometimes in the form of a 'bat-book', a large sheet folded in half, then folded as a leporello.[15]

Eastern Europe

"Scaliger 38b", from the collection of Joseph Justus Scaliger at Leyden University, is a leporello-folded Eastern Orthodox manuscript dated between March 31, 1331, CE and April 19, 1332, CE. The manuscript is made from vellum glued into a strip measuring 378.4 cm by 12 cm, folding down to 12 cm by 4.4 cm and 2.1 cm deep; the vellum is occasionally scored, hypothesized by scholar A. H. van den Boar to allow the vellum to stretch. The manuscript is a personal prayer book, synthesized from many church canons.[16]

Mesoamerica

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica made folding-book manuscripts from amate. There are few surviving codices[b] from before the Spanish conquest of Mexico and Yucatán, due to Spanish Christian book burnings.[17]

Southeast Asia

Summarize

Perspective

Mainland Southeast Asia

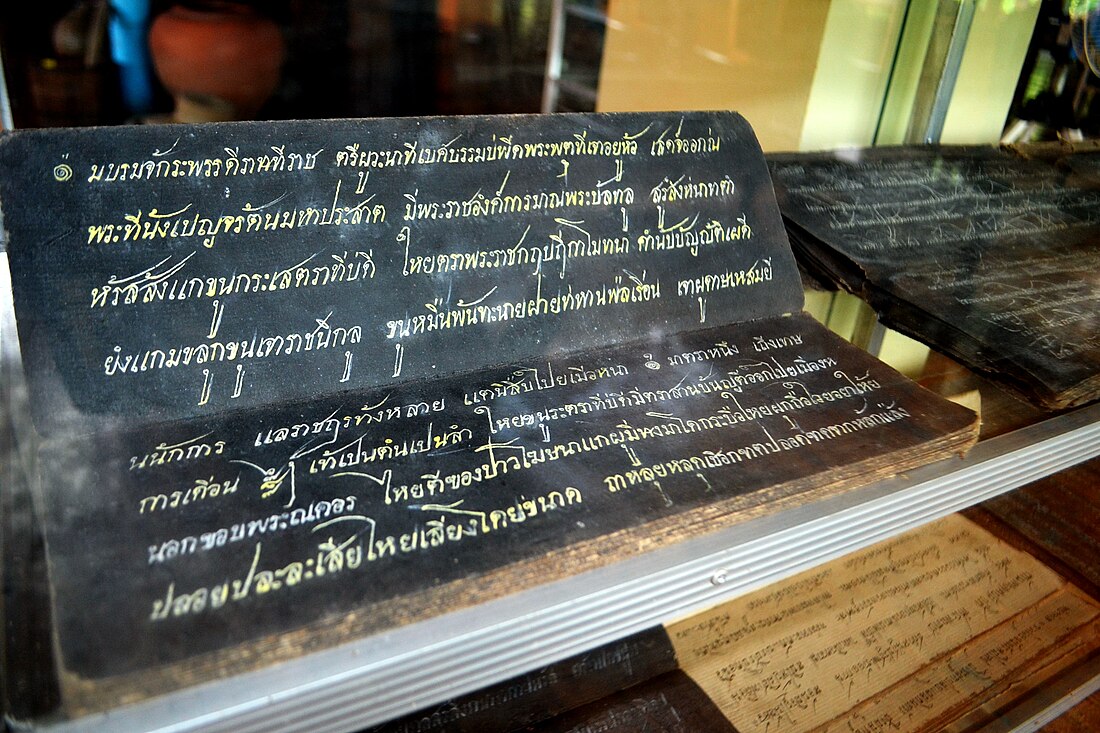

Mainland Southeast Asian folding manuscripts are typically made either of the thicker khoi paper, or the more delicate saa paper. The paper is glued into a very long sheet and folded in a concertina fashion, with the front and back lacquered to form protective covers or attached to decorative wood covers. The unbound books are made in natural, white or black varieties; the paper is respectively undyed, treated with rice flour, and blackened with soot or lacquer.[18][19][20]

They are known as parabaik in Burmese,[c] samut thai in Thai[d] or samut khoi in Thai and Lao,[e] phap sa in Northern Thai and Lao,[f] and kraing in Khmer.[g]

Myanmar

Along with paper made from bamboo and palm leaves, parabaik (ပုရပိုက်) were the main medium for writing and drawing in early modern Burma/Myanmar.[21]: 4–14 The Universities' Central Library in Yangon houses the country's largest collection of traditional manuscripts, including 4,000 parabaiks.[22]

There are two types of parabaik: historically, black parabaik (ပုရပိုက်နက်) were the main medium of writing, while the white parabaik (ပုရပိုက်ဖြူ) were used for paintings and drawings. The extant black parabaik consist of works of scientific and technical importance like medicine, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, history, social and economic commentary, music, historical ballads, fiction, poetry, etc. The extant white parabaik show colored drawings of kings and court activities, stories, social customs and manners, houses, dresses, hair styles, ornaments, etc.[21]: 6 The majority of Burmese chronicles were originally written on parabaik.[23]: 37 A 1979 UN study finds that "thousands upon thousands" of rolls of ancient parabaik were found (usually in monasteries and in homes of private collectors) across the country but the vast majority were not properly maintained.[21]: 4–14 Parabaik were typically made from the bark of the khoi tree, which is a type of paper mulberry. The bark was soaked, pounded, and then made into sheets, which were glued together to create long rolls that could be folded up like an accordion.

Thailand

The use of samut khoi in Thailand dates at least to the Ayutthaya period (14th–18th centuries). They were used for secular texts including royal chronicles, legal documents and works of literature, as well as some Buddhist texts, though palm-leaf manuscripts were more commonly used for religious texts.[24][25]

Illustrated folding books were produced for a range of different purposes in Thai Buddhist monasteries and at royal and local courts. They served as handbooks and chanting manuals for Buddhist monks and novices. Producing folding books or sponsoring them was regarded as especially meritorious. They often, therefore, functioned as presentation volumes in honor of the deceased. A commonly reproduced work in the samut khoi format is the legend of Phra Malai, a Buddhist monk who travelled to heaven and hell. Such manuscripts are often richly illustrated.[26]

Cambodia

The paper used for Khmer books, known as kraing, is primarily made from saa paper. In what is now known as Cambodia, kraing literature was stored in pagodas across the country. During the Cambodian Civil War and the subsequent Khmer Rouge regime of the 1960s and 1970s, as many as 80% of the pagodas in Cambodia were destroyed, including their libraries.[27] In Cambodia, only a tiny fraction of the original kraing of the Khmer Empire have survived.[28]

Maritime Southeast Asia

Indonesia

Indigenous Indonesian folding book manuscripts use treated tree bark for the accordion page. The pustaha is a North Sumatran folding book grimoire made from the bark of Aquilaria malaccensis. Other folding book manuscripts that utilize daluang paper (Kawi: ləpihan), and records thereof, exist in other parts of Sumatra and on Java, but were supplanted by the spread of Islam in Indonesia and the ensuing introduction of codices from the spice trade.[29][30]

Remove ads

Gallery

East Asia

- Western Xia (1038 - 1227) Buddhist sutra written in Tangut and bound as a traditional accordion book

- Sutra of the Perfection of Wisdom (1383) [31]

- Nakasone Shōzan's Okinawan manners and customs , illustrated (1889)

- Yamada Yoshitsuna's Striking Views of Mount Fuji (1828) [32]

See also

- Palm-leaf manuscript

- Zangjing ge, scriptural libraries in China

- Kyōzō, scriptural libraries in Japan

- Ho trai, scriptural libraries in Thailand

- Pitakataik, scriptural libraries in Myanmar

- Buddhist Sutra Pavilion, scriptural libraries in Buddhism in general

- Tripiṭaka tablets at Kuthodaw Pagoda

Notes

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Folding-book manuscripts.

- also 'accordion manuscript', 'leporello manuscript', 'concertina manuscript', 'screenfold manuscript'

- Burmese: ပုရပိုက်; pronounced [pəɹəbaiʔ].

- Thai: สมุดไทย, [sā.mùt tʰāj], 'Thai books'.

- Thai: สมุดข่อย, [sā.mùt kʰɔ̀j]; Lao: ສະໝຸດຂ່ອຍ; 'khoi books', for those made with khoi paper.

- Lao: ພັບສາ; 'folded mulberry paper', for those made with mulberry paper.

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads