Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Phaedo

Dialogue by Plato on the immortality of the soul From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Phaedo (/ˈfiːdoʊ/; Ancient Greek: Φαίδων, Phaidōn) is a dialogue written by Plato, in which Socrates discusses the immortality of the soul and the nature of the afterlife with his friends in the hours leading up to his death. Socrates explores various arguments for the soul's immortality with the Pythagorean philosophers Simmias and Cebes of Thebes in order to show that there is an afterlife in which the soul will dwell following death. The dialogue concludes with a mythological narrative of the descent into Tarturus and an account of Socrates' execution.

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

The dialogue is set in 399 BCE, in an Athenian prison, during the last hours prior to the death of Socrates. It is presented within a frame story by Phaedo of Elis, who is recounting the events to Echecrates, a Pythagorean philosopher.[1]

Characters

Speakers in the frame story:

- Phaedo of Elis: a follower of Socrates, a youth allegedly enslaved as a prisoner of war, whose freedom was purchased at Socrates' request. He later founded a school of philosophy.[2]

- Echecrates of Phlius: A Pythagorean philosopher about whom little else is known.[1]

Speakers in the main part of the dialogue:

- Socrates of Alopece: a philosopher in his 70s, sentenced to death by the Athenians for impiety.

- Simmias and Cebes of Thebes: followers of Socrates and students of the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus of Croton. As relayed in the Crito, which takes place a day or two earlier, they had arranged a plan to help Socrates escape from prison and live in exile, which he had declined.[3]

- Crito of Alopece: a childhood friend of Socrates, who unsuccessfully attempts to convince him to escape from prison in the Crito. In the Phaedo, he takes responsibility for Socrates' body after his death and sacrifices a rooster to Asclepius on his behalf.[4]

Other people present:

- Xanthippe, wife of Socrates: early in the dialogue, she becomes distressed, and Socrates has her taken away. Plato's portrayal of her is generally sympathetic, unlike Xenophon and later biographers, who portray her as inter-personally difficult and unpleasant.[5]

- Lamprocles, Sophroniscus, Menexenus, sons of Socrates: aged roughly 17, 11, and 3 respectively.[6]

- Apollodorus of Phaleron: A follower of Socrates who is unable to stop weeping, he is frequently portrayed by others as flamboyant and manic.[7] He also appears in the Symposium, where he relates the narrative of the dialogue to a friend, and in the Apology, where he offers up funds to pay Socrates' fine.[7]

- Critobulus of Alopece, son of Crito

- Hermogenes of Alopece: a follower of Socrates. He is also one of the main speakers in Plato's Cratylus.[8]

- Epigenes, son of Antiphon: A follower of Socrates, about whom nothing else is known.[9]

- Aeschines of Sphettus: a Socratic philosopher who wrote dialogues, some fragments of which survive.[10]

- Antisthenes: a Socratic philosopher and student of Gorgias, he wrote philosophical dialogues and speeches, none of which have survived.[11] Later members of the Cynic school of philosophy saw him as their founder.[11]

- Ctesippus of Paeania: A follower of Socrates, about whom little is known outside his appearance in the Lysis and Euthydemus.[12]

- Menexenus, son of Demophon: A follower of Socrates, he is a speaker in the Lysis and in the Menexenus, which is named after him.[13]

- Phaedondas of Thebes: According to Xenophon,[14] Phaedondas was a member of Socrates' inner circle along with Crito, Simmias, and Cebes.[15] However, nothing else about him is known.[16]

- Euclid of Megara: a Socratic philosopher, founder of the Megarian school. He appears in the prologue of the Theaetetus.[17]

- Terpsion of Megara: A friend of Euclid, about whom little else is known. He also appears with Euclid in the Theaetetus prologue.[18]

Historical context

The Phaedo is Plato's fourth and last dialogue to detail the philosopher's final days, following Euthyphro, Apology, and Crito. According to the dialogues, Socrates has been imprisoned and sentenced to death by an Athenian jury for impiety.

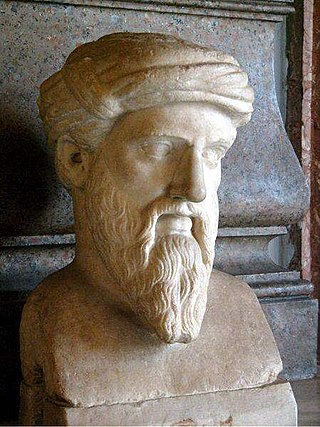

Many of the key characters in the dialogue are associated with Pythagoreanism, a religious and philosophical doctrine that flourished early 5th century BCE, which taught the immortality and reincarnation of the soul after death. Simmias and Cebes are both stated in the dialogue to have studied under Philolaus of Croton,[19] one of the most prominent Pythagorean philosophers,[20] and Echecrates, who is hearing the dialogue from Phaedo, is a Pythagorean from Phlius, which was a stronghold of Pythagoreanism well into the 4th century BCE, when the dialogue is set.[1] Many of the topics that are discussed in the dialogue are thought to derive from the doctrines of Philolaus, including the discussion of suicide, the alternation of opposites, and the harmonic attunement of the soul.[21] Plato himself likely learned Pythagorean doctrines from his close friendship with Archytas of Tarentum, a philosopher and statesman from Magna Graecia who made contributions to mechanics, number theory, and acoustics.[22]

Style, dating, and authorship

The Phaedo is one of the dialogues of Plato's middle period, along with the Republic and the Symposium.[23]

Remove ads

Summary

Summarize

Perspective

The dialogue is told from the perspective of one of Socrates's students, Phaedo of Elis, who was present at Socrates's death bed. Phaedo relates the dialogue from that day to Echecrates, a Pythagorean philosopher.

Phaedo explains that a delay occurred between Socrates' trial and his death, because the trial had occurred during the annual voyage of the Ship of Theseus to Delos, during which time the city is kept "pure" and no executions are performed. Phaedo then tells Echecrates who else was present on the day of the execution, and how Socrates's wife Xanthippe was there, but was very distressed and Socrates asked that she be taken away.[24]

Introduction

Socrates, who has just been released from his chains, remarks on the irony that pleasure and pain, while opposites, are frequently encountered one after the other; people who pursue pleasure often find themselves in pain soon after, while he is experiencing pleasure having been removed from bonds that were causing pains in his leg. Cebes, on behalf of Socrates' friend Evenus, asks Socrates about the poetry he has been writing while in prison, and Socrates relates how, bidden by a recurring dream to "make and cultivate music", he wrote a hymn and then began writing poetry based on Aesop's Fables.[25]

Socrates tells Cebes to "bid Evenus farewell from me; say that I would have him come after me if he be a wise man." Simmias expresses confusion as to why they ought hasten to follow Socrates to death. Socrates then states "... he, who has the spirit of philosophy, will be willing to die; but he will not take his own life." Cebes raises his doubts as to why we should be eager to die, if suicide is prohibited. Socrates replies that while death is the ideal home of the soul, to commit suicide is prohibited as man is not sole possessor of his body, he is actually the property of the gods. But the philosopher always to rid himself of the body even in life, to focus solely on things concerning the soul, because the body is an impediment to the attainment of truth.[26]

Of the senses' failings, Socrates says to Simmias in the Phaedo:

Did you ever reach them (truths) with any bodily sense? – and I speak not of these alone, but of absolute greatness, and health, and strength, and, in short, of the reality or true nature of everything. Is the truth of them ever perceived through the bodily organs? Or rather, is not the nearest approach to the knowledge of their several natures made by him who so orders his intellectual vision as to have the most exact conception of the essence of each thing he considers?[27]

The philosopher, if he loves true wisdom and not the passions and appetites of the body, accepts that he can come closest to true knowledge and wisdom in death, as he is no longer confused by the body and the senses. In life, the rational and intelligent functions of the soul are restricted by bodily senses of pleasure, pain, sight, and sound.[28] Death, however, is a rite of purification from the "infection" of the body. As the philosopher prepares for death his entire life, he should greet it amicably and not be discouraged upon its arrival, for since the universe the gods created for us in life is essentially "good", why would death be anything but a continuation of this goodness? Death is a place where better and wiser gods rule and where the most noble souls serve in their presence: "And therefore, so far as that is concerned, I not only do not grieve, but I have great hopes that there is something in store for the dead ... something better for the good than for the wicked."[29] The soul attains virtue when it is purified from the body: "He who has got rid, as far as he can, of eyes and ears and, so to speak, of the whole body, these being in his opinion distracting elements when they associate with the soul hinder her from acquiring truth and knowledge – who, if not he, is likely to attain to the knowledge of true being?"[30]

Cebes voices his fear of death to Socrates: "... they fear that when she [the soul] has left the body her place may be nowhere, and that on the very day of death she may perish and come to an end immediately on her release from the body ... dispersing and vanishing away into nothingness in her flight."[31]

In order to alleviate Cebes's worry that the soul might perish at death, Socrates introduces four arguments for the soul's immortality:

Cyclical argument

The first argument for the immortality of the soul, often called the Cyclical Argument, supposes that the soul must be immortal since the living come from the dead. Socrates says: "Now if it be true that the living come from the dead, then our souls must exist in the other world, for if not, how could they have been born again?". He goes on to show, using examples of relationships, such as asleep-awake and hot-cold, that things that have opposites come to be from their opposite. One falls asleep after having been awake. And after being asleep, he awakens. Things that are hot came from being cold and vice versa. Socrates then gets Cebes to conclude that the dead are generated from the living, through life, and that the living are generated from the dead, through death. The souls of the dead must exist in some place for them to be able to return to life. Socrates further emphasizes the cyclical argument by pointing out that if opposites did not regenerate one another, all living organisms on Earth would eventually die off, never to return to life.[32]

Recollection argument

Cebes realizes the relationship between the Cyclical Argument and Socrates' Theory of Recollection. He interrupts Socrates to point this out, saying:

... your favorite doctrine, Socrates, that our learning is simply recollection, if true, also necessarily implies a previous time in which we have learned that which we now recollect. But this would be impossible unless our soul had been somewhere before existing in this form of man; here then is another proof of the soul's immortality.[33]

Socrates' second argument, which is based on the theory of recollection as outlined in the Meno,[citation needed] posits that, since it is possible to draw information out of a person who seems not to have any knowledge of a subject prior to his being questioned about it, that implies that the soul existed before birth to carry that knowledge, and is now merely recalling it from memory.[34]

Affinity argument

Socrates presents his third argument for the immortality of the soul, the so-called Affinity Argument, where he shows that the soul most resembles that which is invisible and divine, and the body resembles that which is visible and mortal. From this, it is concluded that while the body may be seen to exist after death in the form of a corpse, as the body is mortal and the soul is divine, the soul must outlast the body.[35]

As to be truly virtuous during life is the quality of a great man who will perpetually dwell as a soul in the underworld. However, regarding those who were not virtuous during life, and so favored the body and pleasures pertaining exclusively to it, Socrates also speaks. He says that such a soul is:

... polluted, is impure at the time of her departure, and is the companion and servant of the body always and is in love with and bewitched by the body and by the desires and pleasures of the body, until she is led to believe that the truth only exists in a bodily form, which a man may touch and see, and drink and eat, and use for the purposes of his lusts, the soul, I mean, accustomed to hate and fear and avoid that which to the bodily eye is dark and invisible, but is the object of mind and can be attained by philosophy; do you suppose that such a soul will depart pure and unalloyed?[36]

Persons of such a constitution will be dragged back into corporeal life, according to Socrates. These persons will even be punished while in Hades. Their punishment will be of their own doing, as they will be unable to enjoy the singular existence of the soul in death because of their constant craving for the body. These souls are finally "imprisoned in another body". Socrates concludes that the soul of the virtuous man is immortal, and the course of its passing into the underworld is determined by the way he lived his life. The philosopher, and indeed any man similarly virtuous, in neither fearing death, nor cherishing corporeal life as something idyllic, but by loving truth and wisdom, his soul will be eternally unperturbed after the death of the body, and the afterlife will be full of goodness.[37]

Simmias confesses that he does not wish to disturb Socrates during his final hours by unsettling his belief in the immortality of the soul, and those present are reluctant to voice their skepticism. Socrates grows aware of their doubt and assures his interlocutors that he does indeed believe in the soul's immortality, regardless of whether or not he has succeeded in showing it as yet. For this reason, he is not upset facing death and assures them that they ought to express their concerns regarding the arguments. Simmias then presents his case that the soul resembles the harmony of the lyre. It may be, then, that as the soul resembles the harmony in its being invisible and divine, once the lyre has been destroyed, the harmony too vanishes, therefore when the body dies, the soul too vanishes. Once the harmony is dissipated, we may infer that so too will the soul dissipate once the body has been broken, through death.[38]

Socrates pauses, and asks Cebes to voice his objection as well. He says, "I am ready to admit that the existence of the soul before entering into the bodily form has been ... proven; but the existence of the soul after death is in my judgment unproven." While admitting that the soul is the better part of a man, and the body the weaker, Cebes is not ready to infer that because the body may be perceived as existing after death, the soul must therefore continue to exist as well. Cebes gives the example of a weaver. When the weaver's cloak wears out, he makes a new one. However, when he dies, his more freshly woven cloaks continue to exist. Cebes continues that though the soul may outlast certain bodies, and so continue to exist after certain deaths, it may eventually grow so weak as to dissolve entirely at some point. He then concludes that the soul's immortality has yet to be shown and that we may still doubt the soul's existence after death. For, it may be that the next death is the one under which the soul ultimately collapses and exists no more. Cebes would then, "... rather not rely on the argument from superior strength to prove the continued existence of the soul after death."[39]

Seeing that the Affinity Argument has possibly failed to show the immortality of the soul, Phaedo pauses his narration. Phaedo remarks to Echecrates that, because of this objection, those present had their "faith shaken", and that there was introduced "a confusion and uncertainty". Socrates too pauses following this objection and then warns against misology, the hatred of argument.[40]

Final argument

Socrates then proceeds to give his final proof of the immortality of the soul by showing that the soul is immortal as it is the cause of life. He begins by showing that "if there is anything beautiful other than absolute beauty it is beautiful only insofar as it partakes of absolute beauty".

Consequently, as absolute beauty is a Form, and so is life, then anything which has the property of being animated with life, participates in the Form. As an example he says, "will not the number three endure annihilation or anything sooner than be converted into an even number, while remaining three?". Forms, then, will never become their opposite. As the soul is that which renders the body living, and that the opposite of life is death, it so follows that, "... the soul will never admit the opposite of what she always brings." That which does not admit death is said to be immortal.[41]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Plato's Phaedo had a significant readership throughout antiquity, and was commented on by a number of ancient philosophers, such as Harpocration of Argos, Porphyry, Iamblichus, Paterius, Plutarch of Athens, Syrianus and Proclus.[42]

Phaedo was the literary model of Saint Gregory of Nyssa's Dialogue on the Soul and Resurrection((peri psyches kai anastaseos)),[43] which he dedicated to the memory of his sister Saint Macrina the Younger.[44]

The two most important commentaries on the Phaedo that have come down to us from the ancient world are those by Olympiodorus of Alexandria and Damascius of Athens.[45]

The Phaedo was first translated into Latin from Greek by Apuleius[46] but no copy survived, so Henry Aristippus produced a new translation in 1160.

The Phaedo has come to be considered a seminal formulation, from which "a whole range of dualities, which have become deeply ingrained in Western philosophy, theology, and psychology over two millennia, received their classic formulation: soul and body, mind and matter, intellect and sense, reason and emotion, reality and appearance, unity and plurality, perfection and imperfection, immortal and mortal, permanence and change, eternal and temporal, divine and human, heaven and earth."[47]

Texts and translations

Original texts

- Greek text at Perseus

- Plato. Opera, volume I. Oxford Classical Texts. ISBN 978-0198145691

- Plato. Phaedo. Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics. Greek text with introduction and commentary by C. J. Rowe. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0521313186

Original texts with translation

- Plato: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo, Phaedrus. Greek with translation by Harold N. Fowler. Loeb Classical Library 36. Harvard Univ. Press (originally published 1914).

- Fowler translation at Perseus

- Plato: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo. Greek with translation by Chris Emlyn-Jones and William Preddy. Loeb Classical Library 36. Harvard Univ. Press, 2017. ISBN 9780674996878 HUP listing

Translations

- The Last Days of Socrates, translation of Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo. Hugh Tredennick, 1954. ISBN 978-0140440379. Made into a BBC radio play in 1986.

- Plato: Phaedo. Hackett Classics, 2nd edition. Hackett Publishing Company, 1977. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. ISBN 978-0915144181

- Plato. Complete Works. Hackett, 1997. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. ISBN 978-0872203495

- Plato: Meno and Phaedo. Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy. By David Sedley (Editor) and Alex Long (Translator). Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0521676779

Remove ads

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads