Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Post-punk

Subgenre and period of rock music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Post-punk is a subgenre and era of rock music that emerged in late 1977 in the wake of punk rock. The concept was originally outlined by Jon Savage in his "New Musick" editorial for Sounds magazine in November 1977. The term has been noted for lacking a universally agreed-upon definition. Post-punk musicians departed from punk's fundamental elements and raw simplicity, adopting instead a broader, more experimental approach that incorporated a variety of avant-garde sensibilities and non-rock influences. Inspired by punk's energy and DIY ethic but determined to move beyond rock clichés, artists drew influence from German krautrock and experimented with styles such as funk, electronic music, jazz, and dance music; the production techniques of dub and disco; and ideas from modernist art, cinema, literature, and politics. They also established independent record labels, created visual art, staged multimedia performances, and produced fanzines. Among the early post-punk bands, only Siouxsie and the Banshees and Public Image Ltd. achieved commercial success in 1978, with debut singles reaching the top ten of the UK Chart.

Regional scenes developed across Europe alongside new wave music, the most notable being the Netherlands' Ultra movement, Germany's Neue Deutsche Welle, Spain's La Movida Madrileña, and the coldwave scenes in France, Poland, and Belgium, as well as the Soviet and Yugoslav new wave. The original post-punk era emerged in parallel with the no wave and industrial music scenes, and later provided a foundation for British new pop and the Second British Invasion in the United States. Post-punk also influenced the development of numerous alternative and independent music genres, including gothic rock, neo-psychedelia, dark wave, dance-punk, jangle pop, ethereal wave, dream pop, and shoegaze. By the mid-to-late 1980s, post-punk had largely dissipated.

During the 2000s, several New York bands incorporated post-punk influences into contemporary indie rock, leading to the dance-punk and post-punk revival. By the 2010s, Canadian, Irish, Danish and American post-punk acts later inspired London's Windmill scene and "crank wave", while post-punk became briefly associated with the internet microgenre "doomer wave", sometimes associated with Russian post-punk and darkwave acts in the early 2020s. Around the same time, regional scenes developed in Russia and Latin America.

Remove ads

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

Origins

Post-punk is an era and diverse genre that emerged from the cultural milieu of punk rock in the late 1970s.[1][nb 1] In 1976, New York poetry magazine Contact published the earliest known use of the term "post-punk" in an interview with painter and poet Jack Micheline, the interviewer asked Micheline, "What are your thoughts moving in a post-punk beat period?".[3]

On 26 November 1977, Sounds magazine published an issue entitled "New Musick", with editorials by English journalists Jane Suck and Jon Savage. Savage wrote a piece on an emerging scene and style of music known as "new musick", suggesting that punk rock was becoming stagnant and evolving into new, more experimental forms, which he noted as "post punk projections". He mentioned Pere Ubu, while describing Throbbing Gristle and Devo as promoting "spontaneous physical reaction". He described the style as exhibiting "more overt reggae/dub influence", sounding "the same/manufactured in a factory," and characterized Subway Sect, the Prefects, Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Slits, and Wire as exploring "harsh urban scrapings/controlled white noise/massively accented drumming".[4][5]

Music historian Clinton Heylin stated, "it would be a while before New Musick metamorphosed into post-punk, these cub reporters were already hoping to chart punk’s future course."[6] Observers such as Simon Reynolds, David Wilkinson,[7] and Theo Cateforis have cited Savage's editorial as the starting point for post-punk as a musical genre.[8] Writer David Wilkinson states, "there was a sense of renewed excitement about what would be dubbed 'post-punk'".[9][nb 2] According to writer Ian Gittins, some journalists opted for the term "art punk" to describe artists who "delivered garage rock’s adrenalin rush with a moderate degree of intelligence", though it was sometimes used by critics as a pejorative.[11][nb 3]

Heylin cites that in March 1979, Simon Frith proposed the term "Afterpunk" in an issue of Melody Maker, which stated "1979 is the year of Afterpunk", though Heylin defined the term as a "non-starter", further stating, "he [Frith] did recognize that punk was changing, nay evolving; and, like [Paul] Morley, he predicted that the battle would be between the chart-conscious and the art-conscious, or as he designated them, the populists and the progressives".[13] At the time, "post-punk" was used interchangeably with "new musick"[14] and "new wave", though by the early '80s the terms became differentiated as their styles perceptibly narrowed.[15]

Definition

Additionally, post-punk is often understood not only as a musical genre, but also as a period of alternative music. Reynolds defined the post-punk era as occurring roughly between 1978 and 1984.[16][9] He asserted that the post-punk period produced significant innovations and music on its own.[17] He described the period as "a fair match for the sixties in terms of the sheer amount of great music created, the spirit of adventure and idealism that infused it, and the way that the music seemed inextricably connected to the political and social turbulence of its era".[18] Musicologist Mimi Haddon notes that post-punk lacks a universally agreed-upon definition, and has argued that Reynolds’ account of the genre fails to reflect contemporary consensus found on the Internet, citing artists such as the Chameleons and Echo & the Bunnymen as examples that fall outside his definition of a "post-punk vanguard".[19]

Observers such as Mimi Haddon, Simon Reynolds,[20] David Buckley, David Wilkinson and Alex Ogg have noted that several artists associated with post-punk predated the late-1970s punk explosion.[21] Haddon argues that the prefix “post-” in post-punk need not be understood solely in a chronological sense. Drawing on multiple linguistic meanings of "post-," through citing the definition for postmodern feminism by political theorists Carolyn Dipalma and Kathy Ferguson.[22] Haddon proposes definitions in relation to postmodernism, noting the prefix can function as a noun ("the postmodern") denoting a vantage point from which one assesses punk, as well as a verb ("to post"), in the sense of announcing or signposting punk's limitations and consciously or unconsciously critiquing perceived shortcomings in punk while seeking new musical directions.[23]

Writer Ian Trowell echoed this interpretation stating, "We can consider the meaning of post as a simple temporal delineator (as in post-war or a post-watershed television programme) or an ontogenetic shift in genre and thinking (as in postmodern)".[24]

Remove ads

Characteristics

Summarize

Perspective

Although post-punk is associated with a specific period of alternative music, the term also refers to a subgenre of rock music.[25][26] Additionally, it has been characterized as the "ugly twin sister" of new wave music by Scott Rowley of Louder. Discussing the term, he said: "It describes artists inspired by punk in some way – maybe by its ability to address issues, its flouting of convention, or just by its sheer energy."[27] The genre is known for its distinctive approach to rhythm, instrumentation, and atmosphere. While rooted in punk rock's rawness, it diverges through experimental influences and unconventional structures, absorbing elements from various global music traditions, often pushing boundaries beyond punk's simplicity.[28][29]

Simon Reynolds advocated that post-punk be conceived as "less a genre of music than a space of possibility",[30][1] suggesting that "what unites all this activity is a set of open-ended imperatives: innovation; willful oddness; the willful jettisoning of all things precedented or 'rock'n'roll'".[16] Reynolds remarked that post-punk was "not all fractured guitars and angst-racked vocals - it could also be eccentric and ethereal".[30] Although post-punk aims to defy convention, many identifiable musical traits and patterns can still be found across the genre, such as melodic basslines, angular guitars, steady drumming, and spoken singing.[31]

Writer Nicholas Lezard described the term "post-punk" as "a fusion of art and music" and "so multifarious that only the broadest use ... is possible".[7] He wrote that the music of the period "was avant-garde, open to any musical possibilities that suggested themselves, united only in the sense that it was very often cerebral, concocted by brainy young men and women interested as much in disturbing the audience, or making them think, as in making a pop song".[32] Artists defined punk as "an imperative to constant change" rather than a standardized template, believing that "radical content demands radical form".[33] Though the music varied widely between regions and artists, post-punk has been characterised by its "conceptual assault" on rock conventions.[17][32][34][17][1][35]

Remove ads

Influences

Summarize

Perspective

In the 1970s and early 1980s, British post-punk bands were shaped by bleak and deteriorating urban environments, abandoned brutalist architecture and widespread social disillusionment brought on by deindustrialization and austerity—trends that intensified under Thatcherism.[36][37][38] In the United States, acts in the New York and Ohio punk scene were similarly inspired by their city's harsh, smog-infested industrial landscape to create jagged, chaotic, and dissonant music.[39]

Artists sought to refuse the common distinction between high and low culture[41] and returned to the art school tradition found in the work of artists such as Roxy Music and David Bowie.[42][43] Author Gavin Butt linked art education as a "really important part of the cultural ecology" of Leeds-based post-punk bands such as Delta 5, Gang of Four, Scritti Politti and the Mekons.[44] Jon Savage identified influences such as the Velvet Underground and Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd, as well as glam rock, krautrock and art rock.[4] Other previous musical styles such as art pop,[45] garage rock, psychedelia and music from the 1960s were also influential.[46][nb 4] Captain Beefheart's polyrhythmic and angular sound also became foundational.[48] Additionally, post-punk absorbed darker and heavier elements from early heavy metal, particularly Black Sabbath. Writer Edmond Maura noted that Sabbath shared commonality with post-punk bands in being influenced by the industrial and bleak environment surrounding them.[49] Although often mythologized as an enemy of the wider punk scene, post-punk also drew from progressive rock, Louder noted: "the post-punk generation were making a new kind of prog".[50] Avant-garde jazz and free jazz also stood out as influences, highlighted by releases like Miles Davis' On the Corner.[51][52][53][54]

Germany's krautrock scene in the early 1970s similarly emerged from a rejection of formal rock conventions, with many post-punk bands citing groups like Can, Neu!, and Faust as key inspirations,[55] while producer Conny Plank, and electronic band Kraftwerk[56] heavily inspired post-punk production techniques; their album Trans-Europe Express was particularly impactful on the development of cold wave.[57][58][59] Post-punk abandoned punk rock's continued reliance on established rock and roll tropes, such as three-chord progressions and Chuck Berry-based guitar riffs in favour of experimentation with production techniques and non-rock musical styles such as dub,[4] reggae,[4] funk,[60] electronic music, disco,[61] noise, world music,[28] and the avant-garde.[28][43][62]

Three key figures—Brian Eno, David Bowie and Iggy Pop—played pivotal roles in advancing post-punk in the UK, with each of them heavily drawing from krautrock influences. Ex-Roxy Music member Brian Eno's debut and sophomore albums would prove influential. So did Pop's The Idiot,[63] produced and largely composed by Bowie, and recorded while in Berlin.[64][65][66] While Bowie's Berlin Trilogy introduced ambient textures, atmospheric production and synthesizers, which were later described as helping to "pave the way for much of post-punk's bleak, futuristic outlook".[67][68]

A variety of groups that predated punk, such as Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle, experimented with tape machines and electronic instruments in tandem with performance art methods and influence from transgressive literature, ultimately helping to pioneer industrial music.[69] Throbbing Gristle's independent label Industrial Records would become a hub for this scene and provide it with its namesake.

In the early-to-mid-1970s, several American bands had already begun expanding the vocabulary of punk music, infusing it with more art-based, literary, and avant-garde influences. Groups associated with New York's CBGB scene—such as Television, Suicide, Talking Heads, and the Patti Smith Group—were notable for pushing punk beyond its raw aggression into more experimental, rhythmically varied, and intellectually driven forms. San Francisco bands like the Residents were also noted as predecessors to post-punk, and later gained commercial success through the new wave scene,[70] while Chrome emerged as a key early post-punk group that blended punk energy with psychedelic elements.[71]

Although post-punk is often viewed as a direct reaction to the explosion of punk rock in 1977, music journalist Simon Reynolds observes that many of the groups later labeled as post-punk had roots predating punk's commercial breakthrough:

The truth is that some of the defining post punk groups were actually prepunk entities that existed in some form or another for several years before the Ramones' 1976 debut album.[20]

Additionally, Reynolds noted a preoccupation among some post-punk artists with issues such as alienation, repression, and technocracy of Western modernity.[72] Among major influences on a variety of post-punk artists were writers William S. Burroughs and J. G. Ballard, with English cultural theorist Mark Fisher noting Burroughs and Ballard as "the most important influences on post-punk, more significant than any musical reference point".[73] Other influences included brutalist architecture,[38] avant-garde political scenes such as situationism, and Dada, along with intellectual movements such as structuralism (deconstruction) and postmodernism.[74] Many artists viewed their work in explicitly political terms.[75] Art films were also an influence on the post-punk generation, particularly Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971)[76] and David Lynch's Eraserhead (1977).[77][78] Additionally, in some locations, the creation of post-punk music was closely linked to the development of efficacious subcultures, which played important roles in the production of art, multimedia performances, fanzines and independent labels related to the music.[79] Many post-punk artists maintained an anti-corporatist approach to recording and instead seized on alternate means of producing and releasing music.[32]

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

On 4 June and 20 July 1976, the Sex Pistols performed at Manchester's Lesser Free Trade Hall. Among the audience were future members of Joy Division and New Order, the Smiths, the Fall, Magazine and Buzzcocks, who all later cited the gig as primarily inspiring their musical careers. Other notable attendees included Martin Hannett, Paul Morley, Jonh Ingham, Tony Wilson, John Cooper Clarke[80] and Alan McGee. Wilson and McGee cited the performance as inspiring the launch of their own influential independent record labels, Factory and Creation Records, which played a key role in the development of Manchester's post-punk, alternative and indie music scenes.[81][17][82]

On 20 September 1976, Siouxsie and the Banshees performed for the first time at the 100 Club Punk Special. They were accompanied by Sid Vicious on drums and Marco Pirroni on guitar, prior to joining Adam and the Ants. The Banshees performance, which involved a 20-minute improvisation based on the "Lord's Prayer", was later retroactively recognized by music journalist John Robb as being "proto post-punk"; Robb compared the rhythm section to PiL's Metal Box released three years later.[83][84]

Writer Alex Ogg stated author and Haçienda DJ Dave Haslam cited "The Prefects and March 1977 as the moment post-punk took root in Brum" which Ogg argued did not fit "chronologically or thematically". Though he regarded Haslam as being "at his best exploring the connections that led Birmingham’s punk generation through to new romanticism. Which, again, is now also seen as a post-punk trope."[85]

As punk rock made its commercial breakthrough in 1977, post-punk artists were initially inspired by punk's DIY ethic and energy,[28] though Reynolds stated by "the summer of 1977, punk had become a parody of itself".[86] The bands ultimately became disillusioned with the style and movement, feeling that it had fallen into a commercial formula, rock convention, and self-parody.[87] They repudiated its populist claims to accessibility and raw simplicity, instead of seeing an opportunity to break with musical tradition, subvert commonplaces and challenge audiences, while rejecting aesthetics perceived of as traditionalist, hegemonic or rockist.[86][88]

Additionally, Reynolds cited songs such as Television Personalities' "Part Time Punks" and Subway Sect's "A Different Story" as self-referential meta critiques that addressed the nature of the punk movement itself.[89]

During the beginning of the punk era, a variety of entrepreneurs interested in local punk-influenced music scenes began founding independent record labels, including Rough Trade (founded by record shop owner Geoff Travis), Factory (founded by Manchester-based television personality Tony Wilson),[90] and Fast Product (co-founded by Bob Last and Hilary Morrison).[91][92] By 1977, groups began pointedly pursuing methods of releasing music independently, an idea disseminated in particular by Buzzcocks' release of their Spiral Scratch EP on their own label as well as the self-released 1977 singles of Desperate Bicycles, which inspired an early British DIY punk movement which included acts such as Swell Maps, 'O' Level, the Homosexuals, Beyond the Implode and Television Personalities.[93] These DIY imperatives would help form the production and distribution infrastructure of post-punk and the indie music scene that later blossomed in the mid-1980s.[94] Notable post-punk era independent record labels included Rough Trade, 4AD, Beggars Banquet, Mute, Industrial, Factory, Fast Records,[95] Glass, and Creation Records.[96][97]

Additionally, the era saw the robust appropriation of ideas from literature, art, cinema, philosophy, politics, and critical theory into musical and pop cultural contexts.[17][98] Mark Fisher later expanded on this idea and moment in pop culture with his notion of "popular modernism", which described post-punk as emblematic of a period in which the avant-garde and mass culture were not opposed but deeply intertwined.[99][100][101][102]

Remove ads

1977–1979: Early years

Summarize

Perspective

United Kingdom

By late 1977, as the initial punk movement dwindled, British acts such as Siouxsie and the Banshees, Subway Sect, the Prefects, the Slits, Alternative TV and Wire were experimenting with sounds, lyrics, and aesthetics that differed significantly from their British punk contemporaries.[103] On 26 November 1977, Jon Savage collectively labelled some of these bands as "new musick".[4] By the 29th of November, Siouxsie and the Banshees performed their first John Peel Session for BBC Radio 1.[104] Music journalist David Stubbs of Uncut retroactively claimed that the performance marked the band as the very first group to make the transition from punk to post-punk, "You can hear it in the 1977 Peel sessions here, on 'Metal Postcard (Mittageisen)' – the space in the sound, the serrated guitars."[104] Mojo editor Pat Gilbert had also stated, "The first truly post-punk band were Siouxsie and the Banshees," noting the influence of the band's use of repetition on Joy Division.[105]

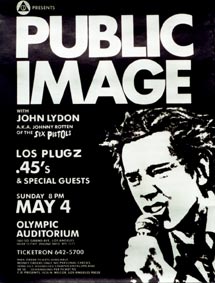

By January 1978, singer John Lydon (then known as Johnny Rotten) announced the break-up of his pioneering punk band the Sex Pistols, citing his disillusionment with punk's musical predictability and cooption by commercial interests, as well as his desire to explore more diverse territory.[106] In May, Lydon formed the group Public Image Ltd[107] with guitarist Keith Levene and bassist Jah Wobble, the latter who declared "rock is obsolete" after citing reggae as a "natural influence".[108] Lydon also drew influence from his other musical interests such as Captain Beefheart, Iggy Pop and the Stooges and Kraftwerk.[109] However, Lydon described his new sound as "total pop with deep meanings. But I don't want to be categorised in any other term but punk! That's where I come from and that's where I'm staying."[110] Later that year, several key acts made releases which helped define British post-punk such as Magazine ("Shot by Both Sides", January 1978), Siouxsie and the Banshees ("Hong Kong Garden", August 1978), Public Image Ltd ("Public Image", October 1978), Cabaret Voltaire (Extended Play, November 1978) and Gang of Four ("Damaged Goods", December 1978).[111][nb 5] According to writer Ken Garner, the music industry initially were "not interested" in Siouxsie and the Banshees, until Polydor Records signed the band, and their debut single reached number 7 on the UK Singles Chart in August 1978.[112][113] Followed by, Public Image Ltd's "Public Image" peaking at number nine in October.[114]

Music historian Clinton Heylin places the "true starting-point for English post-punk" somewhere between August 1977 and May 1978, with the arrival of guitarist John McKay in Siouxsie and the Banshees in July 1977, Magazine's first album, Wire's new musical direction in 1978 and the formation of Public Image Ltd.[115] Music historian Simon Goddard wrote that the debut albums of those bands layered the foundations of post-punk.[116][32] The unorthodox studio production techniques devised by producers such as Steve Lillywhite,[117] Martin Hannett, and Dennis Bovell became important element of the emerging music. Labels such as Rough Trade and Factory would become important hubs for these groups and help facilitate releases, artwork, performances, and promotion.[118][page needed]

Around this time, acts such as Public Image Ltd, the Pop Group and the Slits had begun experimenting with dance music, dub production techniques and the avant-garde,[119] while punk-indebted Manchester acts such as Joy Division, the Fall, the Durutti Column and A Certain Ratio developed unique styles that drew on a similarly disparate range of influences across music and modernist art.[120] Bands such as Scritti Politti, Gang of Four, Essential Logic and This Heat incorporated leftist political philosophy and their own art school studies in their work.[121] Simon Reynolds noted that post-punk reintroduced many of the same qualities such as elitism and intellectualism, found in art rock and progressive rock, stating: "some accused these experimentalists of merely lapsing back into the art rock elitism that punk originally aimed to destroy [...] Of course, not everyone in postpunk attended art school, or even college. Self-educated [...] figures like John Lydon or Mark E. Smith [...] fit the syndrome of the anti-intellectual intellectual".[86]

By 1979, genres such as avant-funk,[122] neo-psychedelia[123][124] and gothic rock[72] grew out of the British post-punk scene, the latter originally pioneered by bands who emphasized darker subject matter in their music such as Siouxsie and the Banshees, Joy Division, Bauhaus, Killing Joke, and the Cure.[125][126] In 1980, Australian band the Birthday Party relocated to the UK to join its burgeoning music scene.

Journalism

As these scenes began to develop, British music publications such as NME and Sounds developed an influential part in the nascent post-punk culture, with writers like Savage, Paul Morley and Ian Penman developing a dense (and often playful) style of criticism that drew on philosophy, radical politics and an eclectic variety of other sources.[127] Reynolds noted these writers as "activist critics", who played a part in "shaping and directing the culture". He noted that they routinely introduced new trends and genre labels, which were often met with backlash, and that their activity contributed to "the surging-into-the-future feeling of the period."[89][127] He stated "critics could actually intensify and accelerate the development of postpunk music".[127] Writer Mimi Haddon cites Jon Savage, Paul Morley, Kris Needs, Paul Rambali, Vivien Goldman, and Chris Brazier as "integral to an understanding of post-punk".[128] In 1978, UK magazine Sounds celebrated albums such as Siouxsie and the Banshees' The Scream, Wire's Chairs Missing, and American band Pere Ubu's Dub Housing.[129] While their 1977 series of articles on "new musick" helped define and bring attention to several early post-punk acts.[8] In 1979, NME championed records such as PiL's Metal Box, Joy Division's Unknown Pleasures, Gang of Four's Entertainment!, Wire's 154 and the Raincoats' self-titled debut.[130]

United States

Devo performing in 1978

Talking Heads were one of the few American post-punk bands to reach both a large cult audience and the mainstream.[131]

Midwestern groups such as Pere Ubu and Devo[132] drew inspiration from the region's derelict industrial environments, employing conceptual art techniques, musique concrète and unconventional verbal styles that would presage post-punk by several years, with Ubu's early singles being described by some writers as "post-punk before punk".[133][134] Music journalist Jon Savage described both bands as "post-punk" on November 26, 1977.[4] While Pere Ubu's first British tour in 1978, including their show at Manchester's Rafters in April that year, significantly influenced the burgeoning English post-punk scene, with Savage noting members of the newly formed Joy Division in attendance.[135]

A variety of subsequent groups, including the Boston-based Mission of Burma[136][137] and the New York-based Talking Heads, combined elements of punk with art school sensibilities, with the latter incorporating elements of Afrobeat and funk on Remain in Light.[138][139] In 1978, Talking Heads began a series of collaborations with British ambient pioneer and ex-Roxy Music member Brian Eno, experimenting with Dadaist lyrical techniques, electronic sounds, and African polyrhythms.[139] San Francisco's vibrant post-punk scene was centered on such groups as Chrome, the Residents, Tuxedomoon and MX-80.[140][141][142] Other American post-punk groups included Suburban Lawns from Long Beach, California.[143][144][145]

Also emerging during this period was downtown New York's no wave scene, as well as a short-lived art and music scene that began in part as a reaction against punk's recycling of traditionalist rock tropes, often reflecting an abrasive and nihilistic worldview.[146][147] No wave musicians such as James Chance and the Contortions, Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, Mars, DNA, Theoretical Girls, and Rhys Chatham instead experimented with noise, dissonance and atonality in addition to non-rock styles.[148] The former four groups were included on the Eno-produced No New York compilation (1978), often considered the quintessential testament to the scene.[149] The decadent parties and art installations of venues such as Club 57 and the Mudd Club would become cultural hubs for musicians and visual artists alike, with figures such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Vincent Gallo,[150] Keith Haring and Michael Holman frequenting the scene.[151] According to Village Voice writer Steve Anderson, the scene pursued an abrasive reductionism that "undermined the power and mystique of a rock vanguard by depriving it of a tradition to react against".[152] Anderson claimed that the no wave scene represented "New York's last stylistically cohesive avant-rock movement".[152]

Remove ads

1980–1984: Further developments

Summarize

Perspective

UK scene and commercial ambitions

British post-punk entered the 1980s with support from members of the critical community—American critic Greil Marcus characterised "Britain's postpunk pop avant-garde" in a 1980 Rolling Stone article as "sparked by a tension, humour and sense of paradox plainly unique in present-day pop music"[153]—as well as media figures such as BBC DJ John Peel, while several groups, such as PiL and Joy Division, achieved some success in the popular charts.[154] The network of supportive record labels that included Y Records, Industrial, Fast, E.G., Mute, Axis/4AD, and Glass continued to facilitate a large output of music. By 1980–1981, many British acts, including Maximum Joy, Magazine, Essential Logic, Killing Joke, the Sound, 23 Skidoo, Alternative TV, the Teardrop Explodes, the Psychedelic Furs, Echo & the Bunnymen and the Membranes also became part of these fledgling post-punk scenes, which centered on cities such as London and Manchester.[155][page needed]

During this period, major figures and artists in the scene began leaning away from underground aesthetics. In the music press, the increasingly esoteric writing of post-punk publications soon began to alienate their readers; it is estimated that, within several years, NME lost half its circulation. Writers like Paul Morley began advocating "overground brightness" instead of the experimental sensibilities promoted in the early years.[156] Morley's own musical collaboration with engineer Gary Langan and programmer J. J. Jeczalik, the Art of Noise, would attempt to bring sampled and electronic sounds to the pop mainstream.[157] Post-punk artists such as Scritti Politti's Green Gartside and Josef K's Paul Haig, previously engaged in avant-garde practices, turned away from these approaches and pursued mainstream styles and commercial success.[158] These new developments, in which post-punk artists attempted to bring subversive ideas into the pop mainstream, began to be categorised under the marketing term new pop.[17]

New Romantic acts like Bow Wow Wow (left) dealt heavily in outlandish fashion, while synthpop artists such as Gary Numan (right) made use of electronics and visual stylisation.

Several more pop-oriented groups, including ABC, the Associates, Adam and the Ants and Bow Wow Wow (the latter two managed by former Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren) emerged in tandem with the development of the New Romantic subcultural scene.[159] Emphasising glamour, fashion and escapism in distinction to the experimental seriousness of earlier post-punk groups, the club-oriented scene drew some suspicion from denizens of the movement but also achieved commercial success. Artists such as Gary Numan, Depeche Mode, the Human League, Soft Cell, John Foxx and Visage pioneered a new synthpop style that drew more heavily from electronic and synthesizer music and benefited from the rise of MTV.[160]

Downtown Manhattan

In the early 1980s, Downtown Manhattan's no wave scene transitioned from its abrasive origins into a more dance-oriented sound, with compilations such as ZE Records' Mutant Disco (1981) highlighting a newly playful sensibility borne out of the city's clash of hip hop, disco and punk styles, as well as dub reggae and world music influences.[161] Artists such as ESG, Liquid Liquid, the B-52s, Cristina, Arthur Russell, James White and the Blacks, and Lizzy Mercier Descloux pursued a formula described by Lucy Sante as "anything at all + disco bottom".[162] Other no wave-indebted artists such as Swans, Rhys Chatham, Glenn Branca, Lydia Lunch, the Lounge Lizards, Bush Tetras, and Sonic Youth instead continued exploring the early scene's forays into abrasive territory.[163]

Remove ads

Mid-1980s – 1990s: Decline

The original post-punk era ended as associated acts turned away from its aesthetics, often in favour of more commercial sounds. Many of these groups would continue recording as part of the new pop movement, with entryism becoming a popular concept.[155][page needed] In the United States, driven by MTV and modern rock radio stations, a number of post-punk acts had an influence on or became part of the Second British Invasion of "New Music" there.[164][155][page needed] Some shifted to a more commercial new wave sound (such as Gang of Four),[165][166] while others were fixtures on American college radio and became early examples of alternative rock, such as R.E.M. One band to emerge from post-punk was U2,[167] which infused elements of religious imagery and political commentary into its often anthemic music.

Online database AllMusic noted that late 1980s bands such as Big Flame, World Domination Enterprises, and Minimal Compact appeared to be extensions of post-punk.[168] Some notable bands that recalled the original era during the 1990s included Six Finger Satellite, Brainiac, and Elastica.[168]

Remove ads

2000s–present: Revivals

Summarize

Perspective

2000s

By the early 2000s, bands such as the Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the Rapture and Interpol spearheaded what became known as the post-punk revival scene. The Strokes' debut album Is This It further proliferated the movement, with the emergence of artists such as LCD Soundsystem, Liars, the Rogers Sisters, the Fiery Furnaces, Radio 4 and !!!.[169] These bands were widely characterised as part of a post-punk or new wave revival.[170][171][172][173] The commercial success of the Strokes also inspiring a new wave of guitar-based indie music in Britain,[168] which was led by bands like Franz Ferdinand, the Futureheads, and Maxïmo Park. Most notable were the Libertines who later influenced the development of the landfill indie movement in the UK which included post-punk revival bands like Kaiser Chiefs, Razorlight and the Cribs.[169][174][175][176][177]

This musical revival coincided with a broader cultural nostalgia for analog technology and retro aesthetics. Reflecting these influences, many of these bands adopted fashion styles reminiscent of 1960s and 1970s rock acts, such as the Velvet Underground and Television, as well as glam rock[178] and the early New York punk scene.[179][180] Artists donned "skinny ties, white belts [and] shag haircuts", contributing to a visual aesthetic that was later retroactively labelled indie sleaze.[181][182][183] The revival showcased an emphasis on "rock authenticity" that was seen as a reaction to the commercialism of MTV-oriented nu metal, hip hop[173] and "bland" post-Britpop groups.[184] By the end of the decade, many of the bands associated with the revival had broken up, were on hiatus, or had moved on to other musical styles, with very few making a significant impact on the charts.[185][175][186]

2010s–2020s

During the 2010s and 2020s, a new wave of experimental post-punk emerged, drawing influences from no wave, art punk, and post-rock,[187] often featuring vocalists who "tend to talk more than they sing, reciting lyrics in an alternately disaffected or tightly wound voice", which was an approach originally penned by Mark E. Smith of the Fall, a band the scene primarily draws influence from.[188] The revival acted in contrast to the 2000s indie-based scene, with the new style originally being spearheaded by groups such as Preoccupations, and Protomartyr[189] in the early 2010s, alongside Parquet Courts,[190] English bands Eagulls, Sleaford Mods and Savages, Danish band Iceage, as well as Canadian bands Ought and Women.[191][192][193]

In the UK and Ireland, post-punk bands such as Yard Act[194] and Dry Cleaning[194] gained popularity alongside "the Windmill scene", named after the Brixton pub of the same name, which was a scene originally spearheaded by Fat White Family. The movement has been referred to by the Ramapo College of New Jersey's Ramapo News in 2025 as "the most significant movement in rock music in the past decade", terms such as "crank wave", "post-Brexit new wave" and "Speedy scene" have also been used to describe the scene.[195][196][194][197] Notable bands associated with the scene include Black Midi, Black Country, New Road, Squid, Shame, Maruja, the Last Dinner Party, Heartworms, Goat Girl, PVA, and, occasionally, Fontaines D.C.[198][199][200][197][201][202][203]

Remove ads

Regional scenes

Summarize

Perspective

Soviet Union

During the 1970s and 1980s, under the Soviet Union, an underground music scene influenced by post‑punk pioneers in the West developed in republics such as Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, and others. In Russia, prominent post-punk acts were centered in Leningrad, such as Kino, Akvarium, Auktyon, Nautilus Pompilius and Piknik.[204][205][206]

Post-Soviet

By the 2010s, artists such as Belarusian band Molchat Doma drew influence from Soviet era post-punk, though were cited as dark wave by The Guardian.[207][208] In the 2020s, countries such as Lithuania began to develop their own post-punk scenes.[209]

Poland

In Poland, acts such as Sikiera, Kryzys, Republika, Kult and Tilt developed their own regionalized extension of post-punk which was at times referred to as "coldwave".[210][211]

Spain

In post-Francoist Spain during the late 1970s and early 1980s, the influence of punk rock led to La Movida Madrileña (The Madrid Scene),[212] a countercultural movement centered in Madrid that emerged after the death of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. The movement musically drew influences from post-punk, synth-pop and new wave music.[213] In the 2010s and 2020s, the Spanish post-punk scene became encompassed by acts such as Depresión Sonora.[214]

Japan

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Japanese post-punk groups such as OXZ emerged out of the underground Kansai no wave scene which consisted of early Japanese punk and noise music artists centered around Osaka, Kobe, Kyoto and other parts of the Kansai region. Artists included Aunt Sally,[215][216][217] INU, Hide, Jojo Hiroshige and SS.[218][219][220] During the 2000s, the Tokyo underground music scene further developed the scene which was now centered around the independent record label Call And Response.[221][222]

Latin America

In Latin America, post-punk expanded into several regional scenes in Puerto Rico, El Salvador, Mexico, Cuba and Colombia.[223]

Remove ads

Related genres

Summarize

Perspective

New musick

New musick is a loosely defined style of music which primarily draws influences from electronic music, particularly the use of synthesizers.[224][225] The term was originally coined after a meeting organized by Sounds editor Alan Lewis involving music journalists Jane Suck, Sandy Robertson and Jon Savage in October 1977.[226] Writer Mimi Haddon argues, the term was initially used by Savage to describe an intellectual evolution of punk rock in efforts to "bring substance to the new wave".[227] Savage notes the label could be thought of as a subsection of post-punk.[14] Simon Reynolds regarded new musick as the "industrial/dystopian science-fiction side of post-punk".[9]

Cold wave

Cold wave is a music genre that emerged out of post-punk and dark wave in late 1970s Europe, particularly France and Belgium. It is characterized by minimalist arrangements, icy synthesizers, melancholic vocals, and detached emotional tones. Bands like Trisomie 21, Asylum Party, and Martin Dupont are often associated with the genre, which shares ties with dark wave and later minimal wave.

Gothic rock

Gothic rock (also known as goth rock or simply goth) is a subgenre of rock music that emerged out of British post-punk during the late 1970s. Characterized by minor chords, reverb, dark arrangements, and melancholic melodies. The genre became the foundation for the wider goth subculture and influenced related genres like dark wave and ethereal wave.

Dance-punk

Dance-punk (originally known as disco-punk) is a subgenre of post-punk that merges elements of punk rock and dance music. Originally emerging in the late 1970s, the style is characterized by angular guitar riffs, driving basslines, and rhythmic, funk-influenced percussion. Notable acts such as Gang of Four, Liquid Liquid, and ESG helped pioneer the sound, which later saw a revival in the early 2000s through groups like LCD Soundsystem, !!!, and the Rapture.

Dark wave

Dark wave is a music genre that emerged out of new wave and post-punk in the late 1970s, blending gothic atmospheres with synthesizer-driven textures and somber lyricism. It became closely associated with gothic rock, though later evolved into several electronic variants in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly in Germany.

New pop

New pop refers to a movement within early 1980s British popular music that sought to combine the experimental sensibilities of post-punk with mainstream accessibility. Characterized by bright production, stylish presentation, and melodic songwriting, it produced artists such as ABC, The Human League, Culture Club, and Duran Duran, many of whom achieved international commercial success.[228]

Ethereal wave

Ethereal wave (also known as ethereal darkwave or simply ethereal) is a subgenre of dark wave and gothic rock that emerged in the early 1980s. Characterized by lush, reverb-heavy textures, atmospheric guitars, and often female vocals conveying dreamlike or spiritual themes. Notable artists include Cocteau Twins, Dead Can Dance, and This Mortal Coil, many of whom were associated with the 4AD record label.

Doomer wave

Doomer wave (also known as doomerwave or simply doomer) is an online music microgenre coined by anonymous users on 4chan in 2018 to describe an offshoot of the Wojak meme known as "doomer wojak".[229][230] The style was originally associated with slowed down versions of depressive tracks as inspired by the vaporwave microgenre.[230] Writer Cat Zhang of Pitchfork described the "doomer" as "a nihilistic, 20-something male whose despair about the world causes him to retreat from traditional society".[229] The term later expanded to encompass the "doomer girl" archetype.[231] In 2020, Belarussian post-punk band Molchat Doma garnered internet virality through online memes and playlists which referred to them as "Russian doomer music" or "doomer wave".[229][230] Zhang further stated "Perhaps we could think of Molchat Doma’s synth-specked post-punk as a nighttime counterpart to the vaporwave subgenre “mallwave,” which sounds like a eulogy to the lost promise of suburban idyll."

Remove ads

See also

- List of post-punk bands

- Rip It Up and Start Again – 2005 book about post-punk by Simon Reynolds

- Postmodern music – Music of the postmodern era

- Proto-punk – Music which predated the punk movement and subculture

Notes

- According to critic Simon Reynolds, Savage introduced the term "new musick", which may refer to the more science-fiction and industrial sides of post-punk.[10]

- In rock music of the era, "art" carried connotations that meant "aggressively avant-garde" or "pretentiously progressive".[12] Additionally, there were concerns over the authenticity of such bands.[11]

- Biographer Julian Palacios specifically pointed to the era's "dark undercurrent", citing examples such as Pink Floyd's Syd Barrett, the Velvet Underground, Nico, the Doors, the Monks, the Godz, the 13th Floor Elevators and Love.[46] Music critic Carl Wilson added the Beach Boys' leader Brian Wilson (no relation), writing that elements of his music and legends "became a touchstone ... for the artier branches of post-punk".[47]

- Gang of Four producer Bob Last said that "Damaged Goods" was post-punk's turning point, saying, "Not to take anything way from PiL – that was a very powerful gesture for John Lydon to go in that direction – but the die had already been cast. The postmodern idea of toying with convention in rock music: we claim that."[111]

Citations

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads