Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

West Africa Squadron

Unit of the British Royal Navy From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The West Africa Squadron, also known as the Preventive Squadron,[1] was a squadron of the Royal Navy whose goal was to suppress the Atlantic slave trade by patrolling the coast of West Africa.[2] Formed in 1808 after the British Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act 1807 and based out of Portsmouth, England,[3] it remained an independent command until 1856 and then again from 1866 to 1867.

The impact of the Squadron has been debated, with some arguing it played a significant or even decisive role in the extermination of the transatlantic slave trade and others arguing it was poorly resourced, hamstrung in the performance of its enforcement duties, plagued by corruption, and not chiefly responsible for the decline and end of the trade. Sailors in the Royal Navy considered it to be one of the worst postings because of the extremely high levels of tropical disease to which its members were exposed. Over the course of its operations, it managed to capture about 6% of the transatlantic slave ships and freed about 150,000 Africans.[4][2] Between 1830 and 1865, almost 1,600 sailors died during duty with the Squadron, principally of disease.[5]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

On 25 March 1807, Britain formally abolished the slave trade and prohibited British subjects from trading in slaves and from crewing, sponsoring, and fitting out any slave ships. The Act also included a clause allowing the seizure of ships without slave cargoes on board but equipped to trade in slaves. The practical implementation of the part of the Act aiming to eliminate the trade as a whole proved an enormous challenge from the start, especially against non-British vessels. The small British force was empowered, in the context of the ongoing Napoleonic Wars, to stop any ship bearing the flag of an enemy nation, making suppression activities temporarily much easier. Being one of the largest slave-trading powers at the time and Britain's close ally against France, however, Portugal in particular managed to evade most of the Act's enforcement for its ships, until February 1810, when, under intense diplomatic pressure from London, the Portuguese government signed a convention that allowed British ships to police Portuguese traffic, meaning Portugal could only trade in slaves from its own African possessions. To boost enforcement, the Admiralty dispatched two further vessels in 1818 to police the African coast.

The privateer (a private vessel operating under a letter of marque) Dart, chasing slavers to profit from the bounties set by the British government, made the first captures of Portuguese slave ships under the 1810 convention. Dart, and in 1813 another privateer, Kitty, were the only two vessels to pursue slavers for profit and thus augment the efforts of the West Africa Squadron. The fact that few, if any, other privateers acted on the side of the Squadron, together with the short duration of the involvement of these two vessels, suggests that private participation did not turn out to be particularly profitable and that the bounties were not set high enough to justify the efforts and risks in the minds of privateers.

With the Napoleonic Wars now over and with victorious Britain in a strong position to shape the post-war settlement, Viscount Castlereagh worked hard to ensure that a declaration against slavery appeared in the text of the Congress of Vienna, along with a commitment by all the signatories to the eventual abolition of the trade. Under sustained British pressure, France had already agreed to cease trading in 1814, and Spain in 1817 agreed to cease all its trade north of the equator. Nevertheless, these early agreements against slave trading that Britain struck with foreign powers were often very weak in practice. For example, until 1835 the Squadron seized foreign vessels only if slaves were found on board. It did not interfere with foreign vessels clearly equipped for the slave trade but with no slaves on board, despite the clause of the Act that officially authorised the Squadron to do just that in the case of British vessels.[6] If slaves were found on board foreign ships, a daunting fine of £100 for each individual slave would be levied. To reduce the total penalty, some slaver captains in danger of being caught started having their captives thrown overboard.[7]

In order to prosecute captured vessels and thereby allow the Navy to claim its prizes, a series of courts were established along the African coast. In 1807, a Vice Admiralty Court was established in Freetown (which became the capital of British Sierra Leone the following year). In 1817, several Mixed Commission Courts were established, replacing the Vice Admiralty Court in Freetown. These Mixed Commission Courts had officials from both Britain and foreign powers, with Anglo-Portuguese, Anglo-Spanish, and Anglo-Dutch courts being established in Sierra Leone.

Unlike the Pax Britannica form of policing that would come into force in the 1840s and 1850s, these earlier efforts to suppress the slave trade sometimes suffered from Britain's countervailing desire, within the context of the newborn Concert of Europe, to keep on reasonably good terms with other European powers and to avert conflicts that could have been provoked by more aggressive enforcement. The actions of the West Africa Squadron were "strictly Governed"[8] by the treaties, and officers could be punished quite severely for overstepping their authority. This tended to make the officers substantially more risk-averse than they would later become in the mid century when Britain could afford to toughen the enforcement without fear of diplomatic disadvantages and when the demand for slaves was shrinking rapidly and the trade was becoming less important to the economies of Western Europe and North America anyway.

Sometimes orders to officers to step up enforcement vastly overestimated the resources provided to the Squadron to carry them out, especially in the years immediately following the passage of the Act and the promulgation of the Congress of Vienna. For example, Commodore Sir George Ralph Collier, with the 36-gun HMS Creole as his flagship, was made the first Commodore of the West Africa Squadron. On 19 September 1818, the Navy sent him to the Gulf of Guinea with the following orders: "You are to use every means in your power to prevent a continuance of the traffic in slaves."[9] He had only six ships, however, with which to patrol more than 5,000 kilometres (3,000 mi) of coast and so could barely dent the traffic in slaves along it, still less prevent its continuance.

In 1819, the Royal Navy created a naval station at Freetown, the coastal capital city of Sierra Leone, Britain's first colony in West Africa. By the end of the 18th century, the city had already become famous as a settlement and a safe haven for freed and escaped African slaves trafficked by all the different slave-trading powers, including not merely those who had previously been put to work in the Americas and Europe but also, notably, those who had managed to evade or foil their abductions. It also earned a reputation as a model city and a stronghold of the world abolitionist movement, which, in fact, tended to admire Sierra Leone as a whole for its early and defiant rejection and eradication of slavery within the borders of the newfound British colony. The Squadron began de facto to base itself at and to coordinate its activities from this station. Most of the Africans rescued by the Squadron chose to settle in Sierra Leone, often in or close to Freetown, for fear of being re-enslaved if they strayed too far from the centre of British authority in West Africa or were simply dropped off elsewhere on the coast amid strangers and without the same degree and proximity of British protection and the eponymous recognition of Freetown as, ab initio, a completely and specifically slavery-free jurisdiction.[2] From 1821, the Squadron also used Ascension Island as a supply depot,[10] before this was moved to Cape Town in 1832.[11]

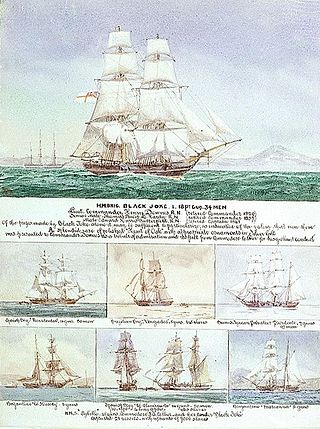

In the early years, determined traders often responded to the Squadron's slowly expanding activities by switching to faster and stealthier ships, particularly Baltimore clippers. At first, British patrollers failed to catch most of these ships, but once the Royal Navy started to use captured slaver clippers themselves, as well as new and improved ships manufactured in Britain, they regained the upper hand. One of the most successful ships of the West Africa Squadron was just such a repurposed Baltimore clipper, HMS Black Joke, which Britain had captured from Brazil in September 1827. Under the Squadron's control, she caught 11 slavers in one year.

By the 1840s, the West Africa Squadron had begun receiving paddle steamers such as HMS Hydra, which proved superior in many ways to the sailing ships they replaced. The steamers were independent of the wind, and their shallow draught allowed them to patrol the shallow shores and rivers. In the middle of the 19th century, there were roughly 25 vessels and 2,000 personnel with a further 1,000 local sailors involved in the enforcement effort.[12]

Britain continued to press other nations into sterner and sterner anti-slaving treaties that gave the Royal Navy increasing authority to search their ships for captive Africans.[13][14] As the 19th century wore on, the Royal Navy also began interdicting slave trading in North Africa, the Middle East, and the Indian Ocean.

The United States Navy assisted the West Africa Squadron in the slave blockade, at first minimally but later consequentially. Joint operations began in 1820 with the dispatch to the West African coast of the USS Cyane, which the United States had, ironically, captured from the Royal Navy in February 1815 in a dramatic 40-minute engagement in the middle of the night off the coast of Portugal, one of the very last incidents of combat in the War of 1812. The US contribution amounted to no more than a few ships, which made up what came to be known simply as the Africa Squadron, until the conclusion of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842, whereupon the contingent grew and strengthened considerably. This treaty and the increase in the size and scope of the US Africa Squadron that followed can be owed largely to the cooling off of relations between the two countries at the time, the ironic alignment in political and other terms of the then interests and initiatives of the Northern urban American Whigs and the rural British Tories (both in central government at the time of the signature of the treaty), and shifts in the balance of international relationships that made cooperation temporarily more beneficial to both parties. Anglo-American cooperation in the suppression of the slave trade in this period drew bitter protest from the pro-free trade Democrat slave-owning planter elite in the southern United States and from the equally pro-free trade British industrialists, generally supportive of Britain's own Whigs and the succeeding Liberals, who relied heavily on the import of cheap raw materials from the slave South for their swift-advancing industrial production and often went on to favour the Confederate side in the American Civil War. The latter did this despite being, by then, predominantly opposed to slavery in their own empire and notionally opposed to slavery and to the economic, social, and political primacy of agriculture as a whole.[15][16]

In 1867, the Cape of Good Hope Station absorbed the West Coast of Africa Station.[17] Incidentally, in 1942, to facilitate the Royal Navy's efforts in the Second World War, the West Africa Station was revived as an independent command but was not maintained after the end of the war in 1945.

Remove ads

Impact

Summarize

Perspective

The West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 ships involved in the slave trade and freed 150,000 slaves who were on board between 1807 and 1860.[18]

Robert Pape and Chaim Kaufmann have described the Squadron as the most expensive international humanitarian intervention in modern history.[19]

Liberated slaves

Slaves rescued by the Squadron were returned to the African mainland, but those who came from more inland regions were usually left to find their own way back to their homes. They often got lost and endured appalling conditions and reverses on their return journeys or had to wait for local courts to resolve the legal complications arising from their emancipation and repatriation, sometimes for inordinately long periods of time.[20] It is estimated that up to a quarter of those rescuees who could not remain or did not wish to remain in Freetown but who could not easily return to their places of origin (a substantial minority out of all the rescuees) died before being fully released from the legal and practical liabilities and entanglements of their past thrall and consequent dislocation.[21] As an alternative to this, many slaves freed by the Squadron, especially the younger among those who hailed from more inland regions, opted to join the Royal Navy or the West India Regiments, typically with the expectation of much faster restoration of their full freedoms in exchange for the near certainty of never being able to get back to their native homes. As another alternative, some (about 35,850, it is estimated) accepted special offers from private British recruiters to work as apprentices in the West Indies.[21]

Remove ads

Criticism

Summarize

Perspective

Journalist Howard W. French has argued that the impact of the Squadron has been overstated, calling it a "central prop" in encouraging a positive image of British history instead of "remorse or even meaningful dialogue about their slave-trading and plantation-operating past."[22] A 2021 paper in the International Journal of Maritime History argued that, despite the enthusiasm of some individual commanders, "the Royal Navy was not wholly committed to ending the slave trade," stating that the Squadron "accounted for less than five per cent of the Royal Navy's warships, comprising a flotilla that was unfit and inadequate given the vast area under patrol."[23]

Mary Wills of the Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation, noted that the Squadron was "bound to ideas of humanitarianism but also increasing desires for expansion and intervention," and noted that it "depended on Africans for the day to day operation of their activities," notably the Kru people.[24] John Rankin of East Tennessee State University has stated that "African and diaspora sailors made up one-fifth of shipboard personnel" and that Kru sailors "were self-organized into collectives, serving on board individual vessels under a single headman who functioned as an intermediary between the British naval and petty officers and his 'Kroo.'"[25]

Working conditions

James Watt has written that crews of the Squadron "were exhausted by heavy rowing under extreme tropical conditions and exposed to fevers with sequelae from which they seldom recovered," and that it had significantly higher sickness and mortality rates than the rest of the Royal Navy.[26]

Senior Officer, West Africa Squadron (1808–1815)

Post holders included:[27]

In command of West Coast of Africa Station

Summarize

Perspective

Commodore, West Coast of Africa Station (1818–1832)

Post holders included:[27]

The West Coast of Africa Station was merged with the Cape of Good Hope Station, 1832–1841 and 1857–60 (Lloyd, p. 68).

Commodore/Senior Officer, on the West Coast of Africa Station (1841–1867)

Post holders included:[27]

From 1867, the commodore's post on the West Coast of Africa was abolished, and its functions absorbed by the senior officer at the Cape of Good Hope.

Remove ads

In popular culture

Summarize

Perspective

The West African Squadron is featured in Lona Manning's historical novels A Contrary Wind (2017) and A Marriage of Attachment (2018).

Patrick O'Brian centres the plot of his 1994 novel The Commodore, the seventeenth instalment in his Aubrey–Maturin series, on his Royal Navy captain, Jack Aubrey, being given command of a squadron to suppress the slave trade off the coast of West Africa near the end of the War of the Sixth Coalition. Though the squadron is never explicitly named the "West Africa Squadron", it fulfills the known roles of the Squadron at the time, and makes reference to the Slave Trade Act 1807.

William Joseph Cosens Lancaster, writing as Harry Collingwood, wrote four novels about the same squadron:

- The Congo Rovers; a Story of the Slave Squadron at Project Gutenberg (1885)

- The Pirate Slaver; a story of the West African Coast at Project Gutenberg (1895)

- A Middy in Command; a tale of the Slave Squadron at Project Gutenberg (1909)

- A Middy of the Slave Squadron at Project Gutenberg (1911)

Captain Charles Fitzgerald is a supporting character in the movie Amistad (1997), giving testimony in support of the Africans' story of enslavement and, at the end, commanding the destruction of the slave fortress of Lomboko.

Remove ads

See also

- Le Louis

- Abolition of slavery timeline § 1800–1849

- African Slave Trade Patrol (United States Navy)

- Black and British: A Forgotten History#3: Moral Mission, a TV series covering the Squadron

- Blockade of Africa

- Category:Ships of the West Africa Squadron

- Mary Faber (slave trader)

- Freetown, Sierra Leone, a town established for the settlement of freed slaves

- Zanzibar slave trade

- Comoros slave trade

- Libyan slave trade

- Trans-Saharan slave trade

- Indian Ocean slave trade

- Red Sea slave trade

Remove ads

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads