Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Primatology

Scientific study of primates From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Primatology is the scientific study of primates.[1] Unlike branches of zoology focused on specific animal groups (such as ornithology, the study of birds), primatology – and the primate order — includes both human and nonhuman animals. Thus, the field entails significant overlap with anthropology, the study of humans, and related sciences.[2]: 178

Primatology encompasses a broad swath of scientists from different fields of study, each with distinct perspectives. For example, behavioral ecologists may focus on ways primate species act in different environments or circumstances. Sociobiologists are concerned with genetic inheritance and primates' physical and behavioral traits. Anthropologists tend to focus on humans' evolutionary history; they look to primates for greater insights into how Homo Sapiens have evolved. Comparative psychologists study differences between human and nonhuman primate minds.

Some primatologists work in the field to study animals in their natural environments; others work in academia in labs conducting experiments. Many do a mix of both. In the 21st century, primatologists have often blended approaches, incorporating both experimentation and observational data to varying degrees.

Many primatologists work outside of academia. In places where nonhuman primates are indigenous — Asia, Africa, and South America — they often work in government to balance human-wildlife coexistence and promote conservation. Primatologists also work in animal sanctuaries, NGOs, biomedical research facilities, museums and zoos.[3]

Remove ads

21st century "primatologies"

Summarize

Perspective

Primatology was established as a discipline in the 1950s in America/Europe and in Japan. (See History below.) International programs — in South America, Africa, and other parts of Asia — began taking off in the 1970s.[4]

Given the wide variety of disciplines involving primates, some specialists speak of primatology not as a single discipline but of multidisciplinary "primatologies." Primatology in the U.S. largely originated with anthropology and its strong bent toward understanding humans and defining human uniqueness. In contrast, "establishing the human-animal divide is generally of little importance to non-Western primatologies."[5]

Researchers from Brazil, India, Vietnam, Africa and areas with indigenous primates have adopted many Western practices while focusing on objectives and approaches that reflect local challenges and cultural traditions. Human populations in these countries have different relationships and experiences with wild primates than do those in the West. The human-primate "interface" (the scientific term for human-nonhuman interactions) is thus a key point of research. Population dynamics, with repeated conservation surveys, form a significant part of research activities for Indian primatologists, for example. Primate rescue centers are key research hubs in Vietnam. Ecology, demography, human-wildlife conflict, and conservation of interconnected species and ecosystems are all possible focal points.[5]

Ethnoprimatology is a 21st-century subdiscipline focused on the social, cultural, and ecological contexts of human-primate interactions. (These interactions have also been viewed as human-wildlife conflict and human-wildlife coexistence.) As habitat loss continues to worsen internationally, primatologists Agustin Fuentes and Kimberley J. Hockings state that understanding which primates are best able to adapt and interface with human populations, and how they are able to do so, is a new frontier for primatology.[6]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Early roots in the West

Primate research has its roots back several centuries. Linnaeus named Primates ("of the highest rank" in Latin) in 1758, placing Homo (humans) in the same taxonomic order as monkeys, apes, lemurs, and bats.[7] This was later revised, and the order primates now includes strepsirrhines (lemurs, galagos, pottos, lorises) and haplorhines (monkeys, apes, and humans).

Charles Darwin's books On the Origin of Species (1859) and The Descent of Man (1871) drew widespread attention to humans' closest relatives. His theory of evolution ignited public fascination with the relationship between humans and monkeys, even a "gorilla craze."[8] Zoologists Ramona and Desmond Morris later credited Darwin for setting off two major trends. One: By connecting humans with other animals, Darwin prompted researchers to consider the behaviour of living animals, especially monkeys and apes, as worthy of detailed scientific study. Two: Researchers inspired by Darwin became prone to highly anthropomorphic interpretations of animal behavior. Once animals were seen as related to humanity, they were viewed as potentially highly rational creatures with exalted moral codes.[9]

Richard Garner, arguably among the first dedicated primate field researchers, personified this tendency. Garner was an innovator in some ways: he built a cage in the African forest to study gorillas in their natural habitat. He recorded primate vocalizations and tested the animal's responses when played back. But his writings included anthropomorphized claims about monkey and ape "speech," stories that provided fodder for outlandish newspaper headlines and illustrations.[9][10]

While scientists from the late-19th and early-20th century were deeply interested in researching evolution, they were wary of being seen as peddling Garner-style primate folklore."[11] In the early 1900s, many Western researchers discounted observational studies as unprofessional and uncontrolled. They viewed lab experiments as the scientific ideal but faced serious complications in building out spaces suitable for primates. Primates are not indigenous to Europe or North America and importing them was expensive.[12][13]

More significantly, those hoping to study primates struggled to keep animals alive. The experience of American scientist Robert Yerkes is illustrative. Yerkes spent $2,000 in 1923[15] — most of his life savings at that point — to buy his first two ape study subjects, Chim and Panzee. Within 5 months, Panzee was dead, and by 12 months, Chim was too.[14] From 1837 to 1965, the average primate in zoos survived about 18 months.[16] Given that apes take a decade or more to reach adulthood, the poor care practices for captive animals meant that studies were bound to be short-term and largely restricted to juveniles.

Yerkes improved his animal care methods after traveling to Cuba to visit wealthy animal-keeper Rosalía Abreu, the first person to successfully breed chimpanzees in captivity. He documented Abreu's practices in Almost Human (1925),[17] in which he identified several factors to improve captive primate care: socially house animals in large, clean spaces with a choice of shade or sunlight; fresh air; sunlight; a varied, appropriate diet and, where possible, space for exercise.[18]

Other early pioneers of primate research include:

- Clarence Ray Carpenter, an American student of Yerkes, was one of the first researchers to scientifically record the behavior of wild primates in the 1930s; He established rigorous methodologies for field scientists to follow.[19]

- Wolfgang Kohler, a German psychologist who conducted seminal experiments on ape cognition, described in his classic The Mentality of Apes (1917).

- Élie Metchnikoff, a Russian immunologist, in 1903 used chimpanzees and orangutans as the first reliable animal models for studying the progression and treatment of human disease, in this case, syphilus.[12]

Racism in primate research

Primate research before the 1950s had roots in eugenics and scientific racism, reflecting and amplifying racist tropes in Western popular culture. Robert Yerkes, often considered the founder of American primatology, promoted primate research in 1925 by arguing that it was the most practical way to "wisely and effectively regulate or control individual, social, and racial existence."[17]: 260 It was practical, he argued, because one could conduct experiments on apes relatively efficiently (compared to humans) without "risk of social censure or legal infringement."[20]

Yerkes was a key American promoter of eugenics, an ideology intended to improve the genetic quality of the human race. Eugenics became hotly criticized and, in the US, started to wane in the 1920s. In effect, Yerkes worked to build a new discipline (primatology) on the remains of an old one (eugenics).[21]

Yerkes was far from alone in this effort. Konrad Lorenz, an Austrian zoologist whose work heavily influenced the development of European primatology, was also an advocate of eugenics. In the early 1940s, Lorenz defended Nazi efforts to prevent interbreeding of different human "races."[22] Richard Garner, the attention-seeking professor of "monkey talk" mentioned above, used his platforms to promote white supremacy in the late 1890s and early 1900s.[23] F.G. Crookshank, a Fellow of Britain's Royal College of Physicians, published a book in 1924 claiming that white people descended from chimpanzees, Black people from gorillas, and "yellow" (Asian) people from orangutans.[24] Crookshank, in line with other racial pseudoscientists, argued that racial "mixing" was dangerous and destructive to the white race.

Significant change to anthropology — and, thus, primate research — came after WWII and the Nazi Holocaust. In the wake of Nazi atrocities perpetrated by beliefs about racial superiority, sciences studying humankind shifted dramatically away from differences between races. Instead, scientists began stressing the unity of the human species. The "new physical anthropology" promoted by Sherwood Washburn, a pioneer in baboon studies, had an antiracist ethos.[25]: 62–63

But while explicit racism in mainstream science waned after WWII, primatology's racist roots have continued to impact the field. Donna Haraway drew attention to the legacy of racism and sexism in primatology in her critical history of the field, Primate Visions (1989).[26] In 2023, the American Journal of Biological Anthropology published an editorial by Thomas C. Wilson, a Black primatologist, outlining ways that the field's racist legacy (in which Black members constituted only .9% of survey respondents) negatively impacts contemporary research.[27]

Establishing primatology in Japan

Primatology emerged as its own distinctive field in the 1950s.[28][4] That decade saw the rise of primatology simultaneously — and largely independently — in both Japan and in the West (North America and Europe). Over time, the traditions blended, but Japanese scientific practice initially differed from that of the Darwin-centered, objectivity-focused researchers overseas.[29] The relationship between humans and other living beings was a deep-seated part of Japanese cultural and intellectual traditions, while the quest for objectivity was not.[29] Japanese scientists assumed monkeys were thinking animals because nonthinking doesn't make sense from an evolutionary perspective. "The problem of mind" in animals was not a problem for the Japanese in the way it was for Western scholars.[30] This opened up Japanese studies to criticism of anthropomorphism and bias, even in cases where their ideas later proved correct.[31]

Unlike Europe and the US, Japan was home to an indigenous monkey species, Japanese macaques, making it relatively easy to observe subjects in the wild. In the 1950s, the tropical areas where most primates live were very difficult (and expensive) for outsiders to access.[32] So while primatology in the West focused on animals in captivity (in zoos and labs), Japanese scientists focused on field research.

Kinji Imanishi and Junichiro Itani, founders of Japanese primatology, studied primate social groups, seeking insights into the origins of human society.[33] They pioneered the following distinct techniques:[34][30]

- Provisioning: Researchers provided food for the monkeys as a short-cut to habituate them, making them easier to observe. This practice was later discouraged out of concerns that it warps natural behaviors.

- Individual identification: Learning to identify every monkey in a troop as an individual was seen as key to understanding the group's dynamics. Japanese researchers also identified primate "personalities."

- Long-term studies over many years and multiple generations were considered necessary to understand group dynamics and society.

The first scientific journal focused on primate research, Primates, was published in Japan in 1957, with English translations. More Japanese studies were translated into English in the 1960s, where they eventually found an audience in the West. Many of their findings — regarding dominance hierarchies, matrilineal residence, the existence of a breeding season — provided foundational understandings of primate socialization internationally.

Perhaps the most widely popularized reports of Japanese origin were those regarding macaque proto-culture. In 1954, Satsue Mito, a field assistant, noticed that one of the female monkeys washed her sweet potatoes before eating them — and that other monkeys in the group were copying the habit. This led researchers to explore how learned behaviors spread in populations, eventually igniting debates around monkey and ape "culture," a subject popularized in the U.S. by Frans de Waal in The Ape and the Sushi Master.[35][25]

Imanishi and Itani went on to co-found the Primate Research Institute at Kyoto University in 1967.

Establishing primatology in Europe and North America

In the period after WWII, primate researchers in the West drew more heavily upon captive animals than did their colleagues in Japan. So, in the 1950s, Western primate research could be roughly lumped into two categories: lab research and field studies. These approaches served wildly different purposes, goals, and methods.

Scientific journals dedicated specifically to primatology appeared later in the West than in Japan. Folia Primatologica launched in 1963, The International Journal of Primatology in 1980, the American Journal of Primatology in 1981, and Primate Conservation in 1981.

Lab research

Innovations in captive animal care and breeding enabled new lines of inquiry in the 1950s. Biomedical researchers saw monkeys and apes as ideal animal models for understanding human disease, and now had the resources to advance experimental testing. Perhaps the most notable medical breakthroughs were the use of Rhesus macaques in making the Salk polio vaccine[36] and chimpanzees in developing the hepatitis B vaccine.[37]

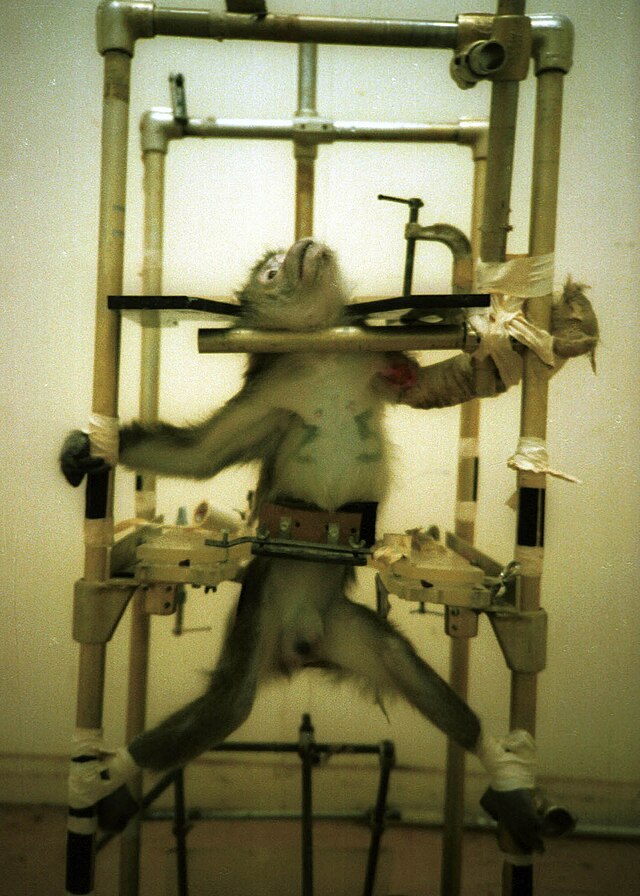

Monkeys and apes were seen as models not only for human anatomy but psychology, and the 1950s and 1960s saw a proliferation of psychological studies using primates. Of these, arguably Harry Harlow achieved the most fame and notoriety, as the initiator of "wire" monkey mother surrogate studies.[38] His research was widely covered in mainstream media, ultimately leading to broad shifts toward more nurturing methods of prenatal, pediatric, and psychological care in humans.[39] Harlow's habit of describing his work in gruesome detail came at a cost, however: it ended up inspiring an organized animal rights movement. This period was captured in a series of articles by Deborah Blum, later compiled into The Monkey Wars. (Blum's research on this controversy received the Pulitzer Prize in 1992.)[40]

Scientific efforts to teach great apes human sign language proved to be more popular with the larger public. Ape sign language studies had their heyday in the early 1970s before a critical study in Science[41] (1979) was seen as debunking the research. As a result, government and foundations cut funding for ape language research.[42] The sign language studies ultimately illustrated a problem with experimental psychology more generally: working with traumatized animals in human-centered, unnatural conditions led to skewed results, even accusations of "pseudoscience."[43][44] Rather than trying to teach apes human language, 21st century explorations of primate communication focused on observing species in their natural habitats.

In the 21st century, many countries have banned or eliminated the use of great apes as biomedical subjects in response to public opposition and efforts such as Project R&R and Great Ape Project, as well as pragmatic concerns. However, researchers continue to use monkeys as experimental subjects, a practice that remains controversial.

Field research

Post-WWII prosperity and improvements in international travel opened up new opportunities for Westerners to study primates in natural environments in the 1950s. R.L. Carpenter resumed research on rhesus macaques that he had translocated to Puerto Rico. Studies on baboons in Africa proliferated. (Unlike other monkeys, baboons live on savannah — not in trees — and thus were seen as better models of human origins.) Studies on "lower," arboreal primates — lemurs and langurs — had a slower start but represented an important development in studying animals for their own sake, not just as "little furry people."[45][46]

Paleontologist Louis Leakey helped organize long-term studies of chimpanzees and gorillas in Africa with Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey in the 1960s. This work coincided with the rise of color television and a new vogue for nature documentaries. The airing of National Georgraphic's Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees in 1965 thus introduced mass audiences to primate fieldwork. The magazine continued to popularize a more naturalistic view of great apes with Fossey's work, as well as that of Biruté Galdikas, who studied orangutans in Indonesia in the 1970s.

Field researchers in the 1980s and 1990s were increasingly forced to confront the destruction of natural habitats, which had been increasing over the century but had reached a fever pitch.[47] Goodall's shift from scientific field work to international conservation and education, reflected a shift in focus that many researchers adopted.

Remove ads

Women in primatology

Summarize

Perspective

Primatology has long been subject to debates regarding researchers' pre-existing opinions and biases. In particular, the use of primatological studies to assert gender roles, and to both promote and subvert feminism has been a point of contention.

The evolution of primatology

Early research on baboon society, starting with Solly Zuckerman's influential The Social Lives of Monkeys and Apes (1932), emphasized male-male aggression and competition for females. Females were described as dedicated mothers to small infants and sexually available to males in order of the males' dominance rank.[48] Female-female competition and choice was ignored.[49] In the 1960s, as more women entered the field, primatologists started looking more closely at female behavior. Studies by Thelma Rowell, Shirley Strum, and Barbara Smuts found that females are active participants, and even leaders, within their groups. For instance, Rowell found that female baboons determine the route for daily foraging.[48] Shirley Strum found that male investment in special relationships with females had a greater payoff —in terms of producing offspring — than their rank in a dominance hierarchy.[50] A field researcher in Madagascar, Alison Jolly, found that females dominated lemur social groups.

In 1970, Jeanne Altmann drew attention to representative sampling methods in which all individuals, not just the dominant and the powerful, were observed for equal periods of time. Prior to Altmann's review, primatologists used "opportunistic sampling," which only recorded what caught their attention, thus preferencing the more physically active and aggressive males.[51]

Sarah Hrdy, a self-identified feminist, was among the first to apply sociobiological theory to primates in her studies of infanticide in langurs.[2]

These female scientists — as well as National Geographic's Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey — forced a reanalysis of how aggression, reproductive access, and dominance affect primate societies.

In the 1970s, media and popular culture portrayed the field of primatology as a science dominated by women. However, the numbers told a more complicated story. A 2011 study found that primatology — like nearly all animal-related studies — drew far more female than male students. Yet most professors of primatology remained male.[52][53]

Remove ads

Notable primatologists

The following is a selected sample of scientists whose work focused on primates and who have shaped the field of primatology. For a larger list, see Primatologists.

- Jeanne Altmann (American)

- Sarah Blaffer Hrdy (American)

- Christophe Boesch (French-Swiss)

- C. R. Carpenter (American)

- Dorothy Cheney (scientist) (American)

- Frans de Waal (Dutch-American)

- Linda Fedigan (American-Canadian)

- Dian Fossey (American)

- Agustin Fuentes (American)

- Birutė Galdikas (Canadian)

- Richard Lynch Garner (American)

- Jane Goodall (English)

- Harry Harlow (American)

- Robert Hinde (English)

- Junichiro Itani (Japanese)

- Alison Jolly (American)

- Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka (Ugandan)

- Nadezhda Ladygina-Kohts (Russian)

- Kawai Masao (Japanese)

- Tetsuro Matsuzawa (Japanese)

- Emil Wolfgang Menzel, Jr. (American)

- Satsue Mito (Japanese)

- Russell Mittermeier (American)

- Toshisada Nishida (Japanese)

- Anne E. Russon (Canadian)

- Robert Sapolsky (American)

- Carel van Schaik (Dutch)

- Robert Seyfarth (American)

- Barbara Smuts (American)

- Karen B. Strier (American)

- Robert W. Sussman (America)

- Michael Tomasello (American)

- Sherwood Washburn (American)

- Richard Wrangham (English)

- Robert Yerkes (American)

Remove ads

Academic resources

Societies

Journals

See also

References

Key Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads