Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Principality of Galicia

Medieval East Slavic principality in the Carpathian region From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

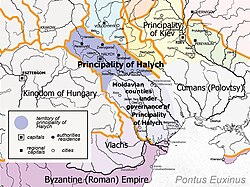

The Principality of Galicia (Ukrainian: Галицьке князівство, romanized: Halytske kniazivstvo; Old East Slavic: Галицкоє кънѧжьство, romanized: Galickoje kǔnęžǐstvo), also known as the Principality of Halych or Principality of Halychian Rus',[1] was a medieval East Slavic principality and one of the main regional states within the political framework of Kievan Rus'. It was established by members of the senior line of the descendants of Yaroslav the Wise.

A distinctive feature of the principality was the significant role of the nobility and townspeople in political life, with princely rule depending largely on their consent.[2] Halych, the capital, was first mentioned around 1124 as the seat of Ivan Vasylkovych, grandson of Rostislav of Tmutarakan.

According to Mykhailo Hrushevsky, the domain of Halych was inherited by Rostyslav after the death of his father, Vladimir Yaroslavich. However, Rostyslav was later expelled by his uncle and moved to Tmutarakan.[3] The territory was subsequently transferred to Yaropolk Iziaslavich, son of the Grand Prince Iziaslav I of Kiev.

Remove ads

Prehistory

Summarize

Perspective

The earliest recorded Slavic tribes inhabiting the territory of Red Rus' were the White Croats and the Dulebes.[4][5][6]

In 907, the Croats and Dulebes took part in the military campaign against Constantinople led by Prince Oleg of Kiev.[7][8] This was the first notable evidence of political alignment among the native tribes of Red Rus'.

According to Nestor the Chronicler, strongholds in the western part of Red Rus' were conquered by Vladimir the Great in 981. In 992 or 993, Vladimir conducted a campaign against the Croats.[9][10] Around this time, the city of Volodymyr was founded in his honour and became the main political centre of the region.

During the 11th century, the western border cities, including Przemyśl, were annexed twice by the Kingdom of Poland (1018–1031 and 1069–1080). Meanwhile, Yaroslav the Wise consolidated Rus' authority in the area, establishing the city of Jarosław.

As part of Kievan Rus', the region was later organized as the southern portion of the Volodymyr Principality. Around 1085, with the support of Grand Prince Vsevolod I of Kiev, the three Rostyslavych brothers—sons of Rostislav Vladimirovich of Tmutarakan—settled in the region. Their lands were divided into three smaller principalities: Przemyśl, Zvenyhorod and Terebovlia.

In 1097, the Council of Liubech confirmed Vasylko Rostyslavych as Prince of Terebovlia, securing his rule after years of civil conflict. In 1124, the Principality of Galicia emerged as a minor polity when Vasylko transferred part of his domain to his son, Ihor Vasylkovich, separating it from the larger Terebovlia Principality.

Remove ads

Unification (1099–1152)

Summarize

Perspective

The Rostyslavych brothers succeeded not only in maintaining political independence from Volodymyr but also in defending their lands against external threats. In 1099, at the Battle of Rozhne Field, the Galicians defeated the army of Grand Prince Sviatopolk II of Kiev. Later that year, they also defeated the army of Hungarian king Coloman near Przemyśl.[11]

These two victories ensured nearly a century of relative stability and development in the Galician principality.[12] The four sons of the Rostyslavych brothers divided the territory into four domains, centred in Przemyśl (Rostyslav), Zvenyhorod (Volodymyrko), Halych, and Terebovlia (Ivan and Yuriy). After the deaths of three of them, Volodymyrko gained control over Przemyśl and Halych, while Zvenyhorod was granted to his nephew Ivan Rostyslavych Berladnyk, the son of his elder brother Rostyslav.

In 1141, Volodymyrko moved his residence from Przemyśl to the more strategically located city of Halych, effectively establishing a unified Galician principality. In 1145, while Volodymyrko was absent, the citizens of Halych supported Ivan Berladnyk's attempt to seize the throne. After Berladnyk's defeat outside Halych, the Principality of Zvenyhorod was incorporated into the Galician lands.

Volodymyrko pursued a policy of balancing relations with neighbouring powers. He consolidated princely authority, annexed several towns from the domain of the Grand Prince of Kiev, and succeeded in retaining them despite conflicts with both Iziaslav II of Kiev and Géza II of Hungary.[13]

Remove ads

Reign of Yaroslav Osmomysl (1153–1187)

Summarize

Perspective

Domestic policies

In 1152, following the death of Volodymyrko, the Galician throne passed to his only son, Yaroslav Osmomysl. Yaroslav began his reign with the Battle of the Siret River in 1153 against Grand Prince Iziaslav, which resulted in heavy losses for the Galicians but ended with Iziaslav's retreat and death soon after. This eliminated the immediate threat from the east, and Yaroslav secured peace with his other neighbours, Hungary and Poland, through diplomacy. He also neutralised his main rival, Ivan Rostyslavych Berladnyk, the senior descendant of the Rostyslavych brothers and former prince of Zvenyhorod.

These diplomatic achievements allowed Yaroslav to focus on domestic development. His rule was marked by construction projects in Halych and other towns, the enrichment of monasteries, and the consolidation of Galician influence in the lower reaches of the Dniester, Prut, and Danube rivers. Around 1157, the Assumption Cathedral was completed in Halych; it was the second largest church in Kievan Rus' after Saint Sophia in Kiev.[14] The city itself developed into a large urban centre, covering approximately 11 × 8.5 kilometres.[15][16]

Despite his strong international position, Yaroslav's rule was influenced by the citizens of Halych, whose collective will he was often compelled to respect, even in matters of personal and family life.

Contacts with the Byzantine Empire

During this period, Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos sought to involve the Rus' principalities in his diplomatic strategy against Hungary. Volodymyrko had earlier been described as Manuel's vassal (hypospondos), but following the deaths of both Iziaslav and Volodymyrko, the situation shifted. With Yuri of Suzdal, Manuel's ally, seizing Kiev, Yaroslav of Galicia adopted a pro-Hungarian stance.[17]

In 1164–65, Manuel's cousin, Andronikos, the future emperor, escaped from captivity in Byzantium and sought refuge at Yaroslav's court in Galicia. The possibility of Andronikos launching a claim to the Byzantine throne with Galician and Hungarian support alarmed Manuel, who pardoned him and secured his return to Constantinople in 1165. A subsequent mission to Kiev, then ruled by Prince Rostislav I of Kiev, produced a favourable treaty and the promise of auxiliary troops. Yaroslav, too, was persuaded to renounce his Hungarian alliance and re-enter the Byzantine sphere of influence. As late as 1200, the princes of Galicia continued to provide military support to the Empire, particularly in campaigns against the Cumans.[18]

Improved relations with Galicia soon benefited Byzantium. In 1166, Manuel launched a major campaign against Hungary, sending two armies in a coordinated assault. One force advanced across the Wallachian Plain into Transylvania via the Southern Carpathians, while the other marched through Galicia with Galician support and crossed the Carpathian Mountains. This campaign resulted in the devastation of the Hungarian province of Transylvania.[19]

Remove ads

"Freedom in princes" (1187–1199)

A distinctive feature of political life in the Galician principality was the strong role played by the nobility and townspeople. The Galicians adhered to the principle of "freedom in princes," under which they invited or expelled rulers and influenced their policies.

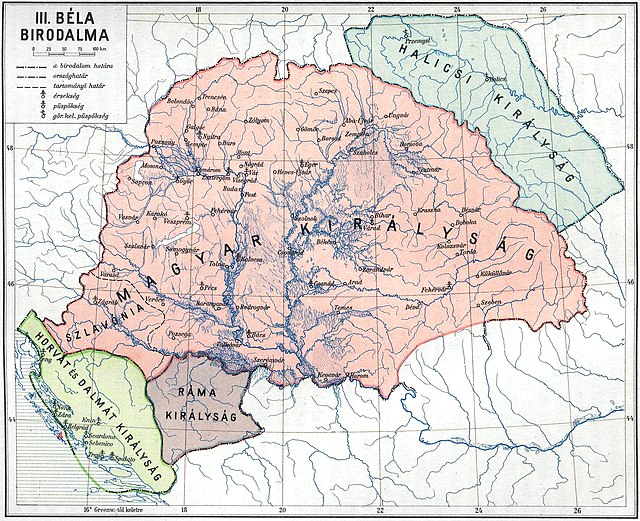

Contrary to the wishes of Yaroslav Osmomysl, who had designated his younger son Oleg as successor, the Galicians invited Oleg's brother Vladimir II Yaroslavich to rule. After conflicts with him, they later turned to Roman the Great, prince of Volodymyr. Roman, however, was soon replaced by Andrew, son of King Béla III. The Hungarian monarch and his son promised the Galicians broad autonomy in government, which was a key reason for their selection.[20][non-primary source needed]

This period is sometimes regarded as the first experiment in self-governance by Galician nobles and citizens. However, dissatisfaction quickly grew due to the misconduct of the Hungarian garrison and attempts to introduce Roman Catholic practices.[21] As a result, Vladimir II was restored to the throne, ruling in Halych until 1199.

Remove ads

Autocracy of Roman the Great and unification with Volhynia (1199–1205)

Summarize

Perspective

After the death of Vladimir II Yaroslavich, the last of the Rostislavich line, in 1199, the Galicians began negotiations with the sons of his sister (daughter of Yaroslav Osmomysl) and with Prince Igor—the central figure of The Tale of Igor's Campaign—regarding succession to the Galician throne. However, Roman the Great, prince of Volodymyr, with the support of Leszek the White, succeeded in seizing Halych despite strong local resistance.[22]

The following six years were marked by repression of the nobility and politically active citizens, alongside significant territorial and political expansion. This period transformed Halych into a major centre of Rus'. The Principality of Volhynia was united with Galicia, with Halych becoming the capital of the new Galicia–Volhynia principality.

Roman defeated the Igorevich brothers, rivals for the Galician throne, and established control over Kiev, installing his allies there with the consent of Vsevolod the Big Nest. Following victorious campaigns against the Cumans and possibly the Lithuanians, Roman reached the height of his power. Contemporary chronicles referred to him as "Tsar and Autocrat of all Rus'."[23][24][25]

After Roman's death in 1205, his widow sought to preserve power in Galicia by appealing to King Andrew II of Hungary, who sent a Hungarian garrison to support her. However, in 1206 the Galicians once again turned to Vladimir III Igorevich, son of Yaroslav Osmomysl's daughter. Roman's widow and sons were forced to flee the city.

Remove ads

Climax of citizens–nobles rule (1205–1238)

Summarize

Perspective

Vladimir III ruled in Galicia for only two years. Following conflicts with his brother Roman II Igorevich, he was expelled, and Roman took the Galician throne. Roman was soon replaced by Rostislav II of Kiev. When Roman regained power after deposing Rostislav, the Galicians appealed to the Hungarian king, who dispatched the palatine Benedict to Halych.[26] While Benedict remained in Halych, the citizens invited Prince Mstislav the Dumb of Peresopnytsia, though he was quickly dismissed. To remove Benedict, the Galicians again turned to the Igorevich brothers—Vladimir III and Roman II—who expelled the Hungarian garrison and re-established their rule. Vladimir III settled in Halych, Roman II in Zvenyhorod, and their brother Svyatoslav in Przemyśl.

The Igorevich brothers' attempts to consolidate rule without consultation led to conflict with the Galicians, during which many nobles were killed.[27] The brothers were later executed, and the throne was offered to Daniel, the young son of Roman the Great. After his mother attempted to assume power as regent, she was expelled, and Mstislav the Dumb was recalled, though he fled fearing the arrival of Hungarian forces summoned by Daniel's mother.

After the failure of the Hungarian campaign, the Galicians took an unprecedented step in Rus' history by enthroning one of their own nobles, Volodyslav Kormylchych, in 1211 or 1213.[28][29][30] This episode is regarded as the peak of citizens–nobles self-rule in Halych.

Volodyslav's rule provoked intervention from neighbouring states. Despite local resistance, foreign forces prevailed. In 1214, King Andrew II of Hungary and Prince Leszek the White of Poland agreed to partition Galicia: the western lands went to Poland, and the rest to Hungary. Benedict returned to Halych, and Andrew's son Coloman received a royal crown from the Pope with the title "King of Galicia." Religious disputes with the local population[31] and the Hungarian occupation of lands promised to Poland, however, led to their expulsion in 1215.

The Galicians then enthroned Mstislav the Bold of Novgorod. Under his rule, political power rested with the nobility,[32][33] and the prince had little control even over the Galician army. Mstislav nevertheless remained unpopular, and support gradually shifted toward Prince Andrew.

In 1227 Mstislav arranged for his daughter to marry Andrew and transferred authority in Galicia to him. Andrew's careful respect for noble privileges secured him a long period of local support. However, in 1233 part of the Galicians invited Daniel back. Following a siege and Andrew’s death, Daniel briefly captured Halych but soon withdrew due to lack of broader backing.

In 1235 the Galicians invited Michael of Chernigov and his son Rostislav Mikhailovich, whose mother was a daughter of Roman the Great and sister of Daniel.[34] During the Mongol invasion of Rus', control of Halych again shifted to Daniel, though his authority remained contested, as chronicles mention the enthronement of the local noble Dobroslav Suddych.[35]

Remove ads

Daniel of Galicia and the Mongol invasion (1238–1264)

In the 1240s, significant changes occurred in the history of the Galician Principality. In 1241, Halych was captured by the Mongol army.[36] In 1245, Daniel achieved a decisive victory over the combined Hungarian–Polish forces of his rival Rostislav Mikhailovich, thereby reuniting Galicia with Volhynia.

Following this victory, Daniel established his residence in Holm in western Volhynia. After visiting Batu Khan, he began paying tribute to the Golden Horde. These developments marked the start of cultural, economic, and political decline in Halych.

Remove ads

Last rise and decline (1269–1349)

During the later years of Daniel's rule, Galicia passed into the hands of his eldest son, Leo I of Galicia, who, after his father's death, gradually extended his authority over all of Volhynia. In the second half of the thirteenth century, he elevated the importance of Lviv, a new political and administrative center founded near Zvenyhorod on the border with Volhynia.

Around 1300, Leo briefly established control over Kiev, although he remained dependent on the Golden Horde. Following Leo's death, the center of the united Galician–Volhynian state shifted back to the city of Volodymyr. Under subsequent rulers, the local nobility gradually regained influence, and from 1341 to 1349 power was effectively exercised by the nobleman Dmytro Dedko, while the Lithuanian prince Liubartas held nominal authority.[37]

In 1349, following Dmytro's death, the Polish king Casimir III the Great marched on Lviv, acting in concert with both the Golden Horde[38] and the Kingdom of Hungary.[39] This campaign marked the end of Galicia's political independence and its annexation into the Polish Crown.

Remove ads

Post-history

In 1387, all the lands of the former Galician principality were incorporated into the possessions of Polish queen Jadwiga. In 1434, the territory was reorganized as the Rus' Voivodeship. Following the first partition of Poland in 1772, Galicia was annexed by the Austrian Empire and established as the administrative unit known as the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, with its center in Lviv.

Relations with the Byzantine Empire

The Galician Principality maintained particularly close ties with the Byzantine Empire, closer than most other principalities of Kievan Rus'. According to some sources, in 1104, Volodar of Peremyshl's daughter Irina married Isaac, the third son of Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos.[40] Their son, the future Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos, reportedly spent time in Halych and governed several cities of the principality in 1164–1165.[41][42]

According to Bartholomew of Lucca, Byzantine Emperor Alexius III fled to Halych following the capture of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204.[43][44]

The Galician Principality and the Byzantine Empire were also frequent allies in campaigns against the Cumans.

Remove ads

Princes of Halych

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads