Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

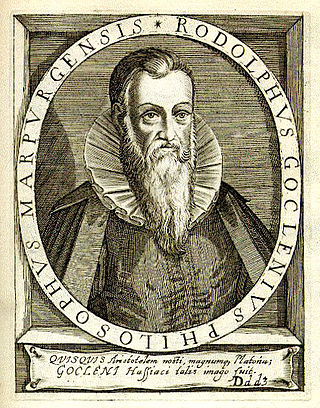

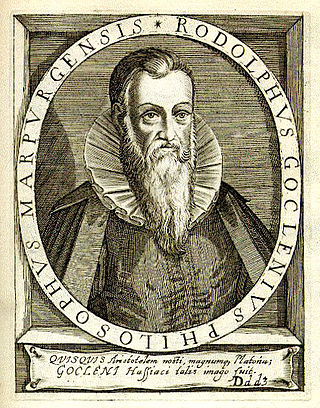

Rudolph Goclenius

German philosopher From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Rudolph Goclenius the Elder (Latin: Rudolphus Goclenius; born Rudolf Gockel or Göckel; 1 March 1547 – 8 June 1628) was a German scholastic philosopher. He is sometimes credited with coining the term psychology in 1590, though the term had been used by Pier Nicola Castellani and Gerhard Synellius 65 years earlier.[1]

Life

Summarize

Perspective

He was born in Korbach, Waldeck (now in Waldeck-Frankenberg, Hesse).

Goclenius studied at the University of Erfurt,[2] the University of Marburg and the University of Wittenberg,[3] earning his M.A. in 1571. While at Wittenberg, Goclenius published his first book, a collection of short poems.[4] In 1573, he returned to Korbach to direct the local gymnasium, and two years later, he took up the same role in Kassel (Michaelmas 1575).[5] Prior to his appointment in Korbach, he had written to the town’s consuls, Antonius Leusmann and Johannes von Ditmarkhausen, urging the restoration of the school, emphasizing the importance of philosophical education, and requesting financial support due to personal hardship.[6] During that period, he also responded to unusual natural phenomena: Jeremias Nicolai, a student at Korbach Stadtschule from Autumn 1574 onwards, brother of Philipp Nicolai, reported that Goclenius "promptly" composed a poem about "fiery air phenomena" (feurige Lufterscheinungen) observed in the city on November 14, 1574.[7] It was published in Marburg later that year.[8] City historian Wolfgang Medding has suggested that this poem was inspired by an aurora,[9] a hypothesis supported by historical records of auroral observations.[10] The atmospheric phenomena Goclenius first addressed poetically in 1574 reappeared in scholarly form three decades later, when he treated auroras ("chasmata") in a 1604 physics textbook.[11]

In 1581, Landgrave Wilhelm IV of Hesse-Kassel, himself a distinguished astronomer, denied Goclenius’s request to return to his hometown of Korbach but instead granted him a professorship at the University of Marburg. Goclenius was officially appointed on September 9 of that year and began his academic career by addressing his colleagues on the subject of physics.[12] Over time, he held chairs in physics, logic, mathematics, and ethics, though the precise date of his appointment to the logic professorship remains uncertain, as noted by historian Franz Gundlach.[13] As of December 18, 1589, Goclenius was still serving as Professor of Physics, a role in which he conferred the title of Magister upon thirty students. His transition to the logic chair is suggested by the preface dated January 13, 1590, to his Three Books of Philosophical Debates, on Certain Logical and Physical Questions, published in Marburg that same year.

Goclenius also acted as a counselor to Wilhelm and his son Moritz, the latter of whom sent him to the Synod of Dort in 1618.[14] Landgrave Moritz appointed the following delegates to represent Hesse-Kassel at the Synod: Georg Cruciger, Paul Steinius, Daniel Angelocrator, and Goclenius. His instructions, dated October 1, 1618, outlined the approach and guidelines for conducting the delegates’ business. Moritz decreed that Steinius would serve as the leading delegate with voting rights. Although Goclenius was initially designated as an extraordinary delegate—“not indeed to sit, but only to listen, and to be consulted privately if necessary”[15]—he was nonetheless granted the opportunity to address the assembly formally. In the sixty-seventh session, held on January 25, 1619, he delivered a speech in which he “thoroughly refuted the principal syllogism of the Remonstrants, which was derived from the execution of predestination, using logical principles.”[16]

Goclenius was frequently consulted for his learned judgment on a variety of matters. In a letter to Otto Melander (dated July 4, 1597), he recounts having been commissioned by Wilhelm IV, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel—through his Chancellor—to investigate the physical causes of witches floating, a task that led him to compose a speech on the subject. In the same letter, Goclenius expressed his approval of Melander’s work refuting the practice of witch purgation by cold water.[17] On the occasion of student performances of Friedrich Dedekind’s The Christian Knight in February 1604 at the Katharineum in Braunschweig, Goclenius responded to a question posed by Rector Johannes Bechmann: “Whether comedies and tragedies are permissible in a well-ordered state.” He argued affirmatively that such plays, when performed with pious intent, contribute significantly to students’ intellectual and ethical development.[18]

In 1627, recognizing the advancing age of Goclenius, Landgrave Moritz made the decision to grant him a peaceful retirement. Moritz directed the professors to nominate suitable successors for the chairs of Logic and Rhetoric. Responding to this directive, the faculty convened and, on June 20th, 1627, recommended Reverend Konrad Greber for the extraordinary professorship of Logic and Dr. Theodor Höpingk for the professorship of Rhetoric.[19] Although officially retired, Goclenius remained active in academic life and continued to participate in examinations throughout the following year. The final exam, however—held just one day before his death—took place in his absence.[20] On the morning of Trinity Sunday, on June 8, 1628, as Goclenius was preparing to go to church, he suffered a stroke and passed away.[21] The previous day, he had dinner with Hermann Vultejus and his son-in-law Christoph Deichmann, Chancellor of Lippe. Vultejus recalled, that Goclenius was mentally sharp and articulate, just as he had been in his younger days. After his burial, which took place two days later, Wolfgang Riemenschneider (Loriseca) gave a speech in which he praised Goclenius as "leader of today's philosophers, Marburgian Plato, European light, Hessian immortal glory".[22]

Johann Balthasar Schupp, a former pupil of Goclenius, later satirically recounted that his teacher had declared the 1598 work Analecta, published in Lich, to be the best book he had ever written. The anecdote appears in Schupp’s Ambassadeur Zipphusius, a satirical allegory in which Zipphusius—a fictional schoolmaster from Mount Parnassus, the mythical seat of the Muses and a symbol of intellectual and artistic excellence—is dispatched to the princes and estates of the Holy Roman Empire with a critique of the educational system.[23]

Remove ads

Family

Summarize

Perspective

Before enrolling at Wittenberg on July 31, 1570, to pursue his master’s degree, Goclenius married his first wife, Margarethe.[24] Abraham Saur, a jurist in Marburg, recorded the following in his chronicle for April 10:

M. Rudolphus Goclerius [sic] holds wedding. On this day / in the year of Christ 1570 as the Sun entered the Sign of Taurus / of which Astrologers say / it is auspicious for marriage / M. Rudolphus Goclerius [sic] / a young learned Man and Poet / celebrated his wedding in Korbach.

— Abraham Saur, Diarium Historicum (1582, p. 155; translated from German)

From this marriage his oldest son, Rudolph Goclenius the Younger, or Rudolf Goclenius, Jr. was born. He went on to become a professor in Marburg and a celebrated mathematician. It is thanks to Rudolph Goclenius, Jr., that a lunar crater bears his name. Additionally, he also worked on cures for the plague and gained fame for his miraculous use with the "weapon salve" or Powder of Sympathy. Among other notable descendants were Theodor Christoph Goclenius (1602–1673, medicine), Eduard Franz Goclenius (1643–1721, law) and Reinhard Goclenius (1678–1726, law).[25] Theodor Christoph was briefly imprisoned following a student riot in May 1626, during which a garrison soldier was wounded in the head and later died, but was released when the injury was ultimately deemed non-lethal.[26] He left Marburg and was entered into the registers of the University of Rostock in December 1626, though without any indication of his origins; his name appears misspelled as "Cocklenius." In 1632, he returned to Marburg, where he earned his doctorate with the thesis Positiones Medicae, though he never pursued an academic career.[27] The thesis reflects a Hippocratic view of human frailty, portraying disease as a fundamental aspect of bodily existence. Eduard Franz studied jurisprudence in Marburg and Rinteln, earning his doctorate in 1666 with the dissertation De Rebus Merae Facultatis. He subsequently held a series of academic appointments at Rinteln: Professor of Logic in 1674, Professor of Law Extraordinary in 1677, and Full Professor in 1680. Reinhard obtained his doctorate in law at Rinteln in 1702 with De Jure Singulari, and went on to serve as Professor of Law at the Gymnasium in Steinfurt, court judge, and senior councilor to the Count of Bentheim.[28]

Remove ads

Philosophical attitude

Summarize

Perspective

Goclenius’s philosophical outlook was grounded in a deep reverence for logic as the organizing principle of both nature and thought. This conviction is expressed in an epigram written during his tenure at Kassel Gymnasium, for the literary games held there in December 1576, where he likens the removal of logic to extinguishing Prometheus’s fire—leaving the world in chaos and darkness. For Goclenius, logic was not merely a tool but the very light by which reality could be apprehended.

The epigram was later included in Wilhelm Adolph Scribonius’s Rerum physicarum, published in Frankfurt in 1577:

If you remove Logic, all knowledge is gone:

And if anything remains, it's mere fable and shadow.

Let the great lamp of Titania be extinguished:

And you'll see everything in blind darkness.

Take away the light of Logic and Prometheus' fire:

And the world will be hidden in small shadows.

Only an inert mass of undigested matter will remain,

And chaos will reign as it did before.

And without a standard, without law, without a certain order,

everything that will be established by us will go.

— Epigramma in Physicas partitiones Adolphi Scribonii, in G. A. Scribonius, Rerum physicarum, juxta leges logicas methodica explicatio, Frankfurt 1577, p. 35.

Goclenius's philosophical views aligned closely with those of Aristotle. He initially belonged to a group known as the “Semiramists,” Aristotelians who advocated both dialectical interpretation of Aristotle's teachings and the exposition of Ramism.[29] Already during his rectorship at the Korbach Stadtschule, Goclenius demonstrated this affiliation by composing a scholarly elegy on Ramus’s death.[30] His commitment to Ramist principles was also recognized by fellow Ramists: Friedrich Beurhusius, in a letter to Johann Thomas Freigius dated September 1575, referred to Goclenius as a devoted follower of Ramus, alongside other schoolmen such as Johann Lambach and Bernhard Copius.[31] Over a decade later, Joannes Bilstenius coined the term “Philippo-Ramism” to describe a refined strand of Ramist thought.[32] Goclenius contributed an "Autoschediasma", a poem that served as a commendatory preface to Bilstenius’s Syntagma Philippo-Rameum artium liberalium (Basel 1588). The poem functions both as a tribute to the work and as a didactic exhortation to aspiring scholars.

In 1610, Johann Heinrich Alsted wrote a manual providing information and advice on academic studies. According to Alsted, Goclenius considered four philosophers—Aristotle, Julius Caesar Scaliger (whose Exercitationes he referred to as his 'Bible'), Jacopo Zabarella, and Jakob Schegk—to be essential reading (cumprimis legendos, meaning "should be read first"). He believed they should form the foundation of what he called the 'Philosophical Library.'[33] Contemporary authors have slightly modified Goclenius's wording to imply that this selection would suffice to fill all the pulpits of philosophers.[34] Another author felt compelled to clear up a contemporary semantic misunderstanding, according to which Goclenius' use of the word 'Bible' in relation to Scaliger's Exercitationes indicates an overestimation of reason among Calvinists.[35]

Remove ads

Works

Summarize

Perspective

In his Disquisitiones Philosophicae (Philosophical Inquiries), published in 1599, Goclenius presents a synoptic table that categorizes philosophical doctrines, or liberal arts, into distinct domains of knowledge.[36] It encompasses two main categories: Real Doctrines and Arts Guiding Our Understanding. Real Doctrines delve into objects of our understanding, including Universal Philosophy (which deals with being in general) and Particular Philosophy (addressing specific beings). Within Particular Philosophy, we find Theoretical (or Real) Philosophy (studying essence and quantity) and Practical (or Moral) Philosophy (focusing on ethics and politics). The practice of Physics is the Art of Medicine. The conjunction of Astronomy and Geography is Cosmography. The second category, Arts Guiding Our Understanding, includes Rhetoric, Grammar, and Logic. Given the diversity of his works, this classification system serves as a useful organizing principle, providing an overview of his writings. Additionally, it helps readers understand how Goclenius conceptually structured the world through his main category of Real Doctrines.

Goclenius authored over 70 books, with more than half of them published between 1589 and 1599. Furthermore, his extensive list of publications includes numerous academic disputations.[37] This can be attributed to the statutes set by Landgrave Philip I on January 14, 1564, which mandated that professors at the University of Marburg conduct weekly examinations.[38] Besides this institutional requirement, Goclenius’s conviction that truth is revealed through debate, whether with oneself or others, also played a significant role.[39] Goclenius delivered three hours of lectures daily: one for the general public (pro lectione publica), one for master's students (pro magistrandis), and one for bachelor's students (pro baccalaureandis).[40]

While Goclenius is known for popularizing the term psychology, his most enduring intellectual legacy lies in the realm of ontology. Building on Aristotle’s foundational work, Goclenius helped establish the discipline of ontology by adopting and advancing its philosophical framework, shaping its development in the 17th century.[41] His use of the term 'ontology' in the Lexicon philosophicum (1613) marked a pivotal moment in the field’s evolution, although the term itself was first introduced by Jacob Lorhard in Ogdoas Scholastica (1606).

Psychology

Goclenius’s contributions to ontology laid the groundwork for future metaphysical inquiry—yet his influence extended beyond this domain. He was instrumental in advancing the emerging knowledge field termed ‘psychology.’ Lecture notes from the University of Marburg indicate that he used the term ‘psychology’ as early as 1582 within the framework of a disciplinary classification, in line with earlier usages by J. T. Freigius (1574) and F. Beurhusius (1581).[42] In 1586, he presided over two academic disputations, during which the word ‘psychology’ again appeared in adjectival form as a classificatory term. Although both disputations addressed the field of psychology, they revealed distinct conceptualizations of the soul or mind. The first thesis highlights the rational powers of the soul (vis cognoscendi & eligendi) as central to the human experience. The second thesis, in contrast, denies that the rational aspect alone constitutes the form of man, suggesting a more integrated view (personaliter) of the human being.[43]

His anthology ΨΥΧΟΛΟΓΙΑ: hoc est, de hominis perfectione, animo, et in primis ortu hujus, published in 1590, became the first book to feature the term 'psychology' in its title.[44] In his dedicatory letter to Hartmann von Berlepsch, Goclenius introduced the theme of the book with an epistemological reflection. He explored the challenging and profound nature of understanding the mind (animus), the differing philosophical views on the sources of truth and knowledge, and the significance of this inquiry despite its difficulty. Regarding the question of the origin of the mind, Goclenius compiled two opposing viewpoints from treatises written between 1579 and 1589. Some suggest that souls are divinely created and placed into bodies (Creationism), while others argue that souls are inherited from parents (Traducianism). He encouraged readers to form their own opinions without condemning differing views. The full title of the book translates to English as 'Psychology: that is, on the perfection of man, his mind, and especially its origin—the comments and discussions of certain theologians and philosophers of our time who are shown on the following page.' In this context, the term 'psychology' refers both to the subject of inquiry ('the perfection of man, his mind, and especially its origin') and to the inquiry itself ('the comments and discussions of certain theologians and philosophers of our time').

Research over the past decades has gradually identified the sources of the treatises since the book lacks bibliographic references in the modern sense.

The 1594 edition added an excerpt from Philosophiae Triumphus (1573) by Nicolaus Taurellus, listed as No. 12. The 1597 edition added excerpts from De Operibus Dei Intra Spacium Sex Dierum (1591) by Girolamo Zanchi and Universae Philosophiae Epitome (1596) by Girolamo Savonarola. These additions led to the renumbering of the subsequent contents, with Savonarola assigned No. 6 and Zanchius No. 7.

In the 17th century, Goclenius' ΨΥΧΟΛΟΓΙΑ was widely read and quoted by scholars such as Robert Burton,[46] Daniel Sennert,[47] and Jakob Thomasius.[48] Goclenius himself revisited his ΨΥΧΟΛΟΓΙΑ in a 1604 textbook on natural science[49] and in various philosophical disputations.[50]

Nevertheless, historians of psychology have disagreed on whether Goclenius, with his ΨΥΧΟΛΟΓΙΑ, aimed at an innovative approach for exploring the soul or to establish psychology as an independent field.[51] Friedrich August Carus, in 1808, had referred to Goclenius' ΨΥΧΟΛΟΓΙΑ as a Lehrbuch ('textbook'), placed in temporal succession to Casmann’s Psychologia anthropologica (1594). However, this was already disputed in the 19th century.[52] Researchers since then have converged in their classification of this book, with some labeling it as a Sammelwerk ('collection', Schüling, 1967), Sammelband ('compilation', Stiening, 1999), or Anthology (Vidal, 2011). This, at least on a linguistic level, is more in line with the fact that Goclenius used the Latin verb 'congessi' (collect, bring together) in his dedicatory letter to Berlepsch to characterize his approach.

Logic

Carveth Read considered Goclenius’ most significant contribution to term logic to be the structure now known as the Goclenian Sorites. In the words of the British logician:

"It is the shining merit of Goclenius to have restored the Premises of the Sorites to the usual order of Fig. I.: whereby he has raised to himself a monument more durable than brass, and secured indeed the very cheapest immortality. How expensive, compared with this, was the method of the Ephesian incendiary!"[53]

The expression “Goclenian Sorites” emerged within the Wolffian school of philosophy, eventually becoming a recognized term in syllogistic logic.[54] The label was used by Johann Peter Reusch, a follower of Christian Wolff and professor at the University of Jena, who attributes the structure to Goclenius, — specifically referencing the Isagoge in Organon Aristotelis (Frankfurt 1598, Part 2, Chapter 4, p. 255ff). Reusch describes the form as one “in which propositions are linked so that the subject of the previous proposition becomes the predicate of the next, until the first predicate is concluded from the last subject.”[55] The following table illustrates the logical flow of Reusch’s example from his Systema Logicum (1734). Each statement builds upon the previous one in reverse order, culminating in the conclusion: “He who is devoted to virtue is happy.”

Goclenius noted in his Isagoge of 1598 that Aristotle remained silent on the Sorites—perhaps, he suggested, because it was regarded as philosophically deceptive. Goclenius, however, rejected this view, arguing that the Sorites was not inherently misleading. When applied in contexts governed by necessary connections—such as between causes and effects, or between genera and species—it could be as legitimate and rigorous as a standard syllogism. In defending its validity, Goclenius challenged the prevailing Aristotelian orthodoxy and sought to rehabilitate the Sorites as a serious instrument of philosophical reasoning. An example of this structure in argumentative context had already appeared in his Dissertatio De Ortu Animi, which concluded the first edition of the ΨΥΧΟΛΟΓΙΑ in 1590.[56]

Yet despite Carveth Read’s assessment, the logical form now known as the Goclenian Sorites was not invented by Goclenius. It appears centuries earlier in the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas, who describes a cumulative syllogistic method in his Commentary on the Metaphysics of Aristotle:

"[A] second demonstration takes as its starting point the conclusion of a first demonstration, whose terms are understood to contain the middle term which was the starting point of the first demonstration. Thus the second demonstration will proceed from four terms the first from three only, the third from five, and the fourth from six; so that each demonstration adds one term. Thus it is clear that first demonstrations are included in subsequent ones, as when this first demonstration—every B is A, every C is B, therefore every C is A—is included in this demonstration—every C is A, every D is C, therefore every D is A; and this again is included in the demonstration whose conclusion is that every E is A, so that for this final conclusion there seems to be one syllogism composed of several syllogisms having several middle terms. This may be expressed thus: every B is A, every C is B, every D is C, every E is D, therefore every E is A."[57]

Remove ads

Publications

Summarize

Perspective

Bibliographies of Goclenius's writings were compiled by Friedrich Wilhelm Strieder (Grundlage zu einer hessischen Gelehrten und Schriftsteller Geschichte, Bd. 4, Göttingen 1784, pp. 428–487; Bd. 9, Cassel 1794, p. 381; Bd. 13, Cassel 1802, pp. 341–343; Bd. 15, Cassel 1806, p. 338) and Franz Joseph Schmidt (Materialien zur Bibliographie von Rudolph Goclenius sen. (1547-1628) und Rudolph Goclenius jun. (1572-1621), Hamm 1979). Schmidt was a historian of medicine based in Hamm (Westphalia). His bibliography is organized into five groups: scientific works, academic writings, occasional writings, writings with Goclenius as editor or author of a foreword, and writings listed in the catalogue of the British Library but not in Strieder's Dictionary. Strieder’s bibliography is arranged chronologically.

- Oratio de natura sagarum in purgatione & examinatione per Frigidam aquis innatantium, Marburg 1584. [A speech delivered at a graduation ceremony on November 19, 1583; republished in Panegyrici Academiae Marpurgensis, Marburg 1590, pp. 190–203; and again, slightly shortened and with typographical errors, in Otto Melander’s Resolutio praecipuarum quaestionum criminalis adversus sagas processus, Lich 1597. The reprint in Melander’s book is preceded by a letter from Goclenius to Melander.]

- Oratio de Nativa et Haereditaria in nobis labe & corruptione, Marburg 1588.

- Problemata logica, pars I 1589, pars II 1590; Pars I-V 1594 (reprint: Frankfurt: Minerva, 1967, in 5 voll.).

- ΨΥΧΟΛΟΓΙΑ: hoc est, de hominis perfectione, animo, et in primis ortu hujus, commentationes ac disputationes quorundam theologorum & philosophorum nostrae aetatis, Marburg 1590; Marburg 1594 (enlarged); Marburg 1597 (enlarged).

- Scholae seu disputationes physicae, Marburg 1591 (new editions: Marburg 1595 & Marburg 1602; Physicae Disputationes, Marburg 1598).

- Partitio dialectica, Frankfurt 1595.

- Isagoge in peripateticorum et scholasticorum primam philosopiam, quae dici consuevit metaphysica, 1598 (reprint: Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1976).

- Institutionum logicarum de inventione liber unus, Marburg 1598.

- Cosmographiae seu sphaerae mundi descriptionis, Marburg 1599.

- Disquisitiones philosophicae, Marburg, 1599.

- P. Rami Dialectica cum praeceptorum explicationibus, Oberursel 1600.

- Appendix IIII. Dialogistica, Marburg 1602.

- Physicae completae speculum, Frankfurt 1604.

- Dilucidationes canonum philosophicorum, Lich 1604.

- Controversia logicae et philosophiae, ad praxin logicam directae, quibus praemissa sunt theoremata seu praecepta logica, Marburg 1604.

- Miscellaneorum Theologicorum Et Philosophicorum, Marburg 1607; Marburg 1608.

- Conciliator philosophicus, 1609 (reprint: Hildesheim, Georg Olms, 1980).

- Lexicon philosophicum quo tanquam clave philosophiae fores aperiuntur, 1613 (reprint: Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1980).

- Lexicon philosophicum Graecum, Marburg 1615 (reprint: Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1980).

The book titled 'Rhapsodus,' from Uffenbach's library, contains a collection of unpublished manuscripts by Goclenius. These manuscripts include letters, observations, dissertations, various critiques, and poems (Bibliothecae Uffenbachianae Universalis, Tomus III, Frankfurt 1730, pp. 488-490).

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads