Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Rus'–Byzantine War (941–944)

940s conflict From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Rus'–Byzantine War of 941 took place during the reign of Igor of Kiev.[n 2] The first naval attack was driven off and followed by another, successful offensive in 944.[6] The outcome was the Rus'–Byzantine Treaty of 945.[7]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

Remove ads

Invasion

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

The Rus' and their allies, the Pechenegs, disembarked on the northern coast of Asia Minor and swarmed over Bithynia in May 941. They seemed to have been well informed that the Imperial capital stood defenseless and vulnerable to attack: the Byzantine fleet had been engaged against the Arabs in the Mediterranean, while the bulk of the Imperial army had been stationed along the eastern borders.

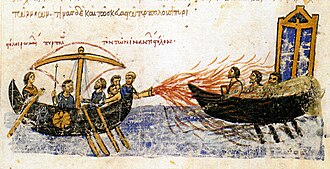

An interesting fact is that Bulgarian tsar Peter I contributed to the Byzantines by warning them about the Rus' attack.[8][9][10][11]Lecapenus arranged a defense of Constantinople by having 15 retired ships fitted out with throwers of Greek fire fore and aft. Igor, wishing to capture these Greek vessels and their crews but unaware of the fire-throwers, had his fleet surround them. Then, at an instant, the Greek-fire was hurled through tubes upon the Rus' and their allies; Liudprand of Cremona wrote: "The Rus', seeing the flames, jumped overboard, preferring water to fire. Some sank, weighed down by the weight of their breastplates and helmets; others caught fire." The captured Rus' were beheaded.[12]

The Byzantines thus managed to dispel the Rus' fleet but not to prevent the pagans from pillaging the hinterland of Constantinople, venturing as far south as Nicomedia. Many atrocities were reported: the Russian Primary Chronicle said that the Rus’ used their victims for target practice or drove nails into their heads.[13] Several Byzantine historians (probably the Russian Primary Chronicle’s source for the information), provide additional details that the Rus’ crucified some of their captives and staked out others on the ground.[14][15]

In September, John Kourkouas and Bardas Phokas, two leading generals, speedily returned to the capital, anxious to repel the invaders. The Kievans promptly transferred their operations to Thrace, moving their fleet there. When they were about to retreat, laden with trophies, the Byzantine navy under Theophanes fell upon them. Greek sources report that the Rus' lost their whole fleet in this surprise attack, so that only a handful of boats returned to their bases in the Crimea. The captured prisoners were taken to the capital and beheaded. Khazar sources add that the Rus' leader managed to escape to the Caspian Sea, where he met his death fighting the Arabs.

Remove ads

Aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

Igor was able to mount a new naval campaign against Constantinople as early as 944/945.[16] Under threat from an even larger force than before, the Byzantines opted for diplomatic action to circumvent invasion. They offered tribute and trade privileges to the Rus'.[17][18][19] The Byzantine offer was discussed between Igor and his generals after they reached the banks of the Danube, eventually accepting them.[20] The Pechenegs that Igor previously hired were left to plunder and raid the Bulgarian lands.[10][11] The Bulgarians however managed to defeat them in a battle.[8] The Rus'–Byzantine Treaty of 945 was ratified as a result.[21] This established friendly relations between the two sides.[22]

According to Shikanov, Igor's second campaign and the subsequent peace treaty were a success for Byzantium because now the prince had to be special. Firstly, merchants were certified with certificates, otherwise they were put in custody, they could enter the city only through one gate in groups of 50 people and without weapons, they were deprived of duty-free trade privileges, and they could not stay for the winter, not only in Constantinople, but even at the mouth of the Dnieper. Secondly, possessions in the Crimea were officially assigned to the Byzantine Empire, moreover, the Russians undertook to protect these territories from nomads. Thirdly, the basileus had the privilege to demand auxiliary troops from the Russian prince. Considering all these factors, the author calls these conditions favourable for byzantine empire.[23]

Vladimir Pashuto notes that Igor's campaigns were not of a conquering nature, but were sanctioned by the desire for profit. In general, the peace was mutually beneficial, as it fulfilled the trade interests of both countries. Rus' position in the Kerch Strait has also strengthened according to peace.[24]

Remove ads

Footnotes

- Sources give varying figures for the size of the Rus fleet. The number 10,000 ships appears in the Primary Chronicle and in Greek sources, some of which put the figure as high as 15,000 ships. Liudprand of Cremona wrote that the fleet numbered only 1,000 ships; Liudprand's report is based on the account of his step-father who witnessed the attack while serving as envoy at Constantinople. Modern historians find the latter estimate to be the most credible. Runciman (1988), p. 111.

- Some scholars have identified Oleg of Novgorod as the leader of the expedition, though according to traditional sources he had been dead for some time. See, e.g., Golb 106-121; Mosin 309-325; Zuckerman 257-268; Christian 341-345.

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads