Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

16 May 1877 crisis

1877 political crisis in France during the Third Republic From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The 16 May 1877 crisis, or more simply the Seize Mai, was a political crisis and institutional crisis that occurred in France during the Third Republic. It pitted the President of the Republic, Marshal Patrice de Mac Mahon, a convinced monarchist, against the republican majority that had emerged from the 1876 legislative elections.

The events took place in a turbulent political context. In the Chamber of Deputies, the republicans led by Léon Gambetta, who sought to break with the lingering Orléanist spirit of the regime, attempted to impose their demands and fiercely opposed ultramontanism. Marshal de Mac Mahon, who reproached the Jules Simon government for its lack of firmness, dismissed it on 16 May 1877. From then on, the situation escalated: left-wing deputies met to sign the manifesto of the 363, which condemned the president's attitude; Mac Mahon in turn appointed the duke Albert de Broglie as head of a government that marked the return of the ordre moral. Mac Mahon dissolved the Chamber on 25 June 1877, but the subsequent legislative elections in October confirmed the republican majority. Initially, President Mac Mahon refused to yield and rumours of a alleged coup d'État circulated, but he eventually submitted and acknowledged his political defeat on 13 December 1877 by recalling the republican Jules Dufaure to the presidency of the Council.

The significance of this political crisis was immense, as it definitively shaped the practical operation of the institutions. It set aside the conservative interpretation of the constitutional laws of 1875, in favour of a strictly republican interpretation of the Constitution in which the government is accountable only to parliament, which invests and dismisses it. The head of state's renunciation of his constitutional prerogatives henceforth placed the executive power under the domination of the legislative power, while the practice of the right of dissolution, although enshrined in the Constitution, disappeared. Furthermore, the 16 May crisis marked the transition between two eras of French democracy and strengthened the rooting in people's minds of a still-nascent republican regime, dashing the hopes of the various monarchist currents of seeing a new restoration established.

An event relatively little studied by historiography, the Seize Mai has left some traces in popular culture and marks an important date for republicans, who regularly referred to it in their political struggles. It was also in the context of this crisis that Victor Hugo published his Histoire d'un crime.

Remove ads

Historical background

Summarize

Perspective

Difficulties of a nascent republic

Initial hesitations between republic and monarchy

On 4 September 1870, amid the ruins of the Second Empire defeated by Prussia, the republic was proclaimed.[1][2][3] In order to stem the insurrection and rule out the prospect of a revolutionary government, the republican deputies agreed on the formation of a Government of National Defense.[4][5] A series of military disasters and the suffering by the people during the siege of Paris ultimately swept away the cabinet despite the determination of Léon Gambetta.[4][5][1] Until 1877, monarchists and republicans engaged in an intense political struggle for control of the institutions and for the legal definition to be given to them.[1]

After the large victory of the monarchists in the legislative elections of 8 February 1871, Adolphe Thiers was appointed "head of the executive power of the French Republic", pending the signature of peace and the restoration of order.[2] Under the leadership of the head of state, who officially received the title of President of the Republic after the passage of the Loi Rivet,[6] the regime gradually moved toward a conservative republicanism.[1] In fact, the monarchists, while awaiting a pretender to the throne, postponed the drafting of a definitive constitution and the provisional institutions evolved slowly,[1] while the republicans advanced in every by-election.[7]

Hopes for a monarchical restoration resurfaced after Thiers's resignation in 1873 and the election of Patrice de Mac Mahon, whose political ambition appeared limited to the return of the king and to "moral order".[6] However, the intransigence of the Count of Chambord, leader of the Legitimist monarchists who demanded the adoption of the white flag in place of the tricolour flag, ruled out any possibility of a royalist restoration in the short term.[8]

On 20 November 1873, the Duke of Broglie had the septennat law passed, an institutional solution that made it possible to further postpone the definitive choice of the nature of the regime and oriented it toward a parliamentary republic, since, because of the reserve and irresponsibility of the President of the Republic, it was up to the Vice-President of the Council to assume responsibility for the executive's actions before the Assembly.[1]

Constitution of the Third Republic (1875)

In his message to the Nation on 6 January 1875, President Mac Mahon urged the Chamber to begin the debate on the regime's constitution, but rather than a sudden conversion to republican ideas, this appeal reflected the growing concern of the monarchists and moderate republicans in the context of a new Bonapartist surge, several deputies of that tendency having been elected the previous year in by-elections.[1][9] The republican principle of the regime appeared definitively established on 30 January 1875 by the adoption, by a majority of one vote (353 against 352), of the Wallon amendment. The latter provided that the President of the Republic is elected for seven years by an absolute majority of votes by the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies meeting as a National Assembly, which marked a decisive turning point: by dissociating the office from its holder, the Wallon amendment institutionalised an impersonal presidency of the Republic.[1][10]

The constitutional laws that followed, passed between February and July 1875, were the result of a compromise between monarchists and republicans and established a parliamentary regime with a strong executive.[10] The President of the Republic was its main actor and enjoyed extensive powers. In addition to the armed forces and the right of pardon, he appointed and dismissed ministers who were responsible to the Chamber of Deputies, with the possibility of dissolving the latter subject to the conforming opinion of the Senate. In legislative matters, the president shared the initiative of laws with the two Chambers. It was his duty to promulgate them after their vote in Parliament, and then to ensure and oversee their execution. Furthermore, since the president was irresponsible, each of his decisions had to be countersigned by a minister who assumed responsibility for it before the Chamber.[11][10]

The government appointed by the president was therefore theoretically accountable both to the president and to the deputies, which made it, according to Professor Marcel Morabito, the "true centre of the opposition between the constituted organs that strive to weigh on its orientation".[12]

Key figures

Extreme Left and Republican Left: 191 seats

Centre Left: 48 seats

Constitutional republicans: 22 seats

Others: 19 seats

Elected President of the Republic by the royalist majority on 24 May 1873 to replace Adolphe Thiers, Patrice de Mac Mahon acted "as absolute master of the executive power" during the early years of his term and, unlike his predecessor, provided himself with a real head of government in the person of Albert de Broglie, Vice-President of the Council of Ministers, a title that marked his submission to the head of state.[14]

Following the elections of 30 January 1876, the Senate retained a narrow conservative majority with 151 seats for the monarchists and Bonapartists against 149 for the republicans.[15][16] In contrast, the legislative elections of February–March 1876 confirmed the trend seen in the most recent by-elections and gave an absolute majority to the republicans, who held nearly 350 sieges in the Chamber of Deputies.[17]

The collapse of the conservatives was experienced as a disaster by President Mac Mahon, who appointed Jules Dufaure to head a government composed of moderate monarchists and centre-left republicans.[18][15] A conservative republican, Dufaure came under pressure from the deputies and his ministry constantly sought compromises.[19] On 9 December, accused by the republican majority of supporting the president's opposition to the amnesty of the Communards, he resigned.[18]

To form the new government, Mac Mahon turned to Senator Jules Simon, who described himself as "profoundly republican and profoundly conservative"[20] .[18]

Close to Adolphe Thiers, Simon had the advantage in the president's eyes of being clearly further to the left than his predecessor while being a notorious opponent of Léon Gambetta, the leader of the republican majority[20] .[18]

Remove ads

Course of events

Summarize

Perspective

The expression "Seize Mai" does not refer only to the events of that day, 16 May 1877, but to the whole of a period "politically agitated and deeply troubled" that ended seven months later with the submission of the head of state.[21]

Origins of the crisis

Simon ministry and the clerical question

For Jules Simon, as for his predecessor, the position was delicate between a monarchist Senate, a conservative president and a republican Chamber.[19] The new President of the Council gave pledges to the left by purging the upper administration (prefects and magistrates), which earned him the hostility of the marshal, but the republicans made increased demands and Gambetta relentlessly tried to put him in difficulty.[22] In the first months of 1877, the religious question agitated the Chamber after bishops had responded to the pope’s appeal by asking their diocesans to send petitions to the President of the Republic urging him to intervene to restore the temporal power of the sovereign pontiff in the face of the Kingdom of Italy.[23]

On 4 May 1877, from the rostrum of the Chamber, Gambetta reproached Jules Simon for having lacked firmness in the face of ultramontane manoeuvres. He denounced "clerical evil […] deeply infiltrated into what are called the ruling classes of the country" and ended his speech by repeating a phrase inspired by his journalist friend Alphonse Peyrat, "Clericalism? That is the enemy!". His motion was adopted without Simon opposing it.[19][22][20]

Thus the religious question revived the confrontation between the republican and conservative blocs and, in this state of heightened tension, President Mac Mahon reproached Jules Simon for being under the influence of a majority radicalised in an anticlerical direction and accused him of being Gambetta’s hostage, especially since on 15 May the President of the Council allowed the Chamber to vote for the repeal of a law punishing press offences against the government’s opinion.[22][18]

- Depicted as a fairground strongman, Jules Simon manages to lift the weight of opportunism in front of a jealous Léon Gambetta. Caricature by André Gill, La Lune rousse, 7 January 1877.

- Jules Simon depicted as a tooth-puller of journalists.

Satire by Pépin of press censorship, Le Grelot, 18 February 1877. - In order to push France down the path of ultramontanism, Jesuits prepare to bombard public opinion and the public authorities with petitions, pastoral letters and other mandements depicted as shells filled with Lourdes water.

Anticlerical caricature by Pépin, Le Grelot, 6 May 1877.

Mac Mahon's letter and Jules Simon's resignation

On 16 May 1877, early in the morning, the president reacted sharply to reading the Journal officiel de la République française which reported the previous day's debate in the Chamber. Considering that Jules Simon's speech departed from the positions agreed in the Council of Ministers, he sent him a letter asking "whether he still had over the Chamber the influence necessary to make his views prevail" and demanding "an explanation […] that is indispensable", justifying his intervention by the sacred idea he had of his office: "if I am not responsible as you are to parliament, I have a responsibility to France, which today more than ever I must be concerned about" .[24][25][22]

A few moments later, the secretary-general of the President of the Republic, Emmanuel d'Harcourt, read the text and, understanding the gravity of the situation, persuaded Mac Mahon to send an usher to retrieve the letter, but in vain. Disavowed, Jules Simon immediately tendered his resignation to the head of state, even though he had not been put in the minority in the Chamber.[25][22] The president accepted it, declaring among other things that he would "rather be overthrown than remain under the orders of Moscow".[26]

Jules Simon then attended the funerals of the former minister Ernest Picard and then those of the former deputy Taxile Delord, where he informed his various ministers and the numerous politicians present of the situation; they were outraged by the presidential move. A meeting of the Republican Left, already scheduled for 3 PM on the Boulevard des Capucines, was opened to the other political groups. It ultimately brought together 200 parliamentarians including a few senators.[27] A plenary meeting was decided for that same evening at the Grand Hôtel where about 300 deputies adopted the motion proposed by Léon Gambetta who, sticking strictly to the legality of the Constitution, recalled that "the preponderance of parliamentary power exercised through ministerial responsibility is the first condition of government of the country by the country". In the letter that the deputy immediately sent to his mistress Léonie Léon, he displayed his determination to lead the fight at the head of the republicans: My dear child, war has been declared, they are even offering us battle: I have accepted it, for my positions are impregnable; we occupy the heights of the law from which we can machine-gun at our leisure the miserable troops of reaction floundering in the plain.[27]

Conflict between the Chamber and the president

Prorogation of the Assembly and manifesto of the 363 (17–18 May)

Marshal Mac Mahon recalled the duke Albert de Broglie to the presidency of the Council and the latter formed a right-wing government that marked the return to the moral order. By appointing a ministry in line with his views, against the opinion of the deputies, the president offered a dualist reading of the constitution: for him the government was as much his emanation as that of the Chamber of Deputies.[16]

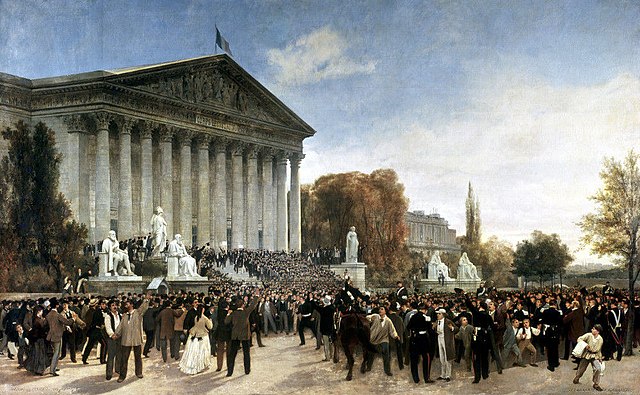

On the morning of 17 May 1877, while the press echoed the crisis, a large crowd gathered shouting "Vive la République!", "Vive Gambetta!", in front of the Gare Saint-Lazare from where the parliamentarians’ trains departed for Versailles.[28] In the Chamber, the right tried to oppose Gambetta speaking, arguing that one could not interpellate a ministry that no longer existed, but the republican deputy, recalling that his speech should not be seen as a movement of hostility towards the President of the Republic, implored him "to return to constitutional truth". He thus intended to show that the crisis opposed two different interpretations of the constitutional laws but that it was in no way a struggle between a majority and an individual.[28] Condemning the appointment of the Duke of Broglie, he asked "whether one wants to govern with the government in all its nuances, or whether, on the contrary, by recalling men rejected three or four times by universal suffrage, one intends to impose a dissolution that would lead to a new consultation of France". The motion defended by Gambetta received 347 votes against 149, the great majority of the deputies of the centre left having joined the other republicans.[28]

The composition of the new government was announced on 18 May 1877. Minister of the Interior, close to Mac Mahon and fervent defender of the moral order, Oscar Bardi de Fourtou read to the deputies the message to the chambers from the President of the Republic which justified his desire to break with radicalism in order to appoint a government to his liking and which he judged in accordance with the expectations of the French.[28] In accordance with the provisions laid down in the Constitution, the president also decided to prorogue the chambers for one month, by decree.[28]

- Parisian onlookers gather on the Boulevard des Italiens to read newspapers reporting the latest news of the institutional crisis (Le Monde illustré, 26 May 1877).

- Following the dismissal of Jules Simon at the start of the crisis, Albert de Broglie forms a new cabinet. But if the Wheel of Fortune continues to turn, Gambetta could come to power. Caricature by Alfred Le Petit on the waltz of ministries, Le Grelot, 3 June 1877.

- The Broglie government protected by a soldier, sabre drawn against the monstrous beast of radicalism. Bonapartist caricature by Nox (La Jeune Garde, 27 May 1877).

Immediately after the close of the sitting, the republican deputies gathered in the office of Senator Émile de Marcère at the Hôtel des Réservoirs. Léon Gambetta proposed drafting an address to the country that would constitute "an act of protest against the policy irregular, if not in the letter, at least in the spirit of the Constitution". A deputy then mentioned the Address of the 221 that had led to the dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies by King Charles X in 1830. Gambetta immediately took up the idea because he believed that such an address must bring about the definitive fall of the conservatives: "Imagine what the reflux of this ocean of universal suffrage will be, pushing before it and casting forever onto the shore all the wreckage of the Ancien Régime".[28] The text, written for the most part by his friend Eugène Spuller, took the name of manifesto of the 363, from the number of deputies who added their signatures. It affirmed that "France wants the Republic" and that "she will show by her calm, her patience, her resolution, that an incorrigible minority cannot wrest from her the government of herself".[28] The three left-wing groups in the Senate for their part added a similar declaration.[28]

- Representations of the manifesto of the 363.

- Text of the manifesto printed on a silk handkerchief.[29]

- Commemorative handkerchief of the republican union, reproducing the portraits of Thiers and Gambetta as well as "the coat of arms of Paris, surmounted by a battlemented crown and accompanied by the motto Fluctuat nec mergitur".[29]

- Medallion portraits of the 363 signers of the manifesto.

Broglie government and return to moral order

The government took advantage of the one-month prorogation of the Assembly, during which it could not be overthrown, to take a series of measures: the Minister of the Interior dismissed numerous prefects (177) and sub-prefects (606),[30] most often replacing them with former senior Bonapartist officials whose mission was to relentlessly prosecute press, publishing or peddling offences. Local elected officials were affected by these measures: 1,743, or 4% of mayors, and 1,334 adjuncts were dismissed, and 613 city councils were dissolved.[31][32][33] 133 secretaries-general and 170 prefectural councillors were also transferred or dismissed.[30] Albert de Broglie sent a circular to the public prosecutors that testified to his firmness: "Among the laws whose guardianship is entrusted to you, the most sacred are those which, starting from principles superior to all political constitutions, protect morality, religion, property and the essential foundations of any civilised society. In whatever form the lie may appear, as soon as it is uttered publicly, it can be punished".[34] Prosecutors as well as justices of the peace were in turn removed.[34]

Taking advantage of their parliamentary immunity, the republican deputies waged the fight by organising public meetings in their constituencies, but also in the press. On Gambetta's initiative, a "general committee of resistance and propaganda" brought together newspapers of all tendencies and met in the offices of his own daily newspaper, La République française. The republicans insisted above all on the fight against clericalism rather than on the constitutional question, which was less likely to arouse public opinion. The conservatives themselves seemed divided, the Orléanists and the Legitimists appearing more reserved than the Bonapartists regarding the appropriateness of President Mac Mahon's initiative.[34]

Abroad, the crisis provoked numerous reactions and, with the exception of the Vatican, European newspapers were unanimous in defending the parliamentarism of the republicans or denouncing clerical manoeuvres.[34]

- Moral order measures caricatured by Draner in Le Charivari.

- A senior official inquires about the durability of his prefect's uniform from a tailor convinced that the garment will outlast his client's prefectural career.

- A prefect seizes a rural guard reading "a subversive newspaper", in this case Le Petit Parisien (a radical and anticlerical newspaper in its early days).

- Witty remark relating to a prosecution for a publishing offence. Le Charivari, “Actualités”, 11 September 1877.

Dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies (16–25 June)

On 16 June 1877, one month after its prorogation, the Chamber met again but the marshal immediately dissolved it, in accordance with Article 5 of the law of 25 February 1875.[35] That same day, he asked the Senate for its "conforming opinion", as the Constitution provided.[36][22]

After reading the presidential message to the deputies, Oscar Bardi de Fourtou addressed the republicans:

We are the France of 1789 arrayed against the France of 1793. We do not have your confidence, you do not have ours. […] The men who are in the government were part of that National Assembly of 1871 which liberated the territory.

Deputy Gustave Gailly replied: pointing at Adolphe Thiers, he exclaimed "The liberator of the territory, there he is!", which aroused the enthusiasm of the left and the centre. Gambetta then delivered a speech lasting more than two hours in which he notably accused the Vatican of having "engineered the whole operation of 16 May". The motion of no confidence, proposed by the presidents of the left-wing groups, confirmed the unity of the republicans in the crisis: it was adopted on 19 June by 363 votes to 158.[36] Confident of his camp’s imminent success, Gambetta declared: "We are leaving as 363, we shall return as 400".[37]

The Senate’s opinion was given on 22 June: by 149 votes to 130, it proved favourable to the presidential will. The Chamber was dissolved three days later, on 25 June.[36][22][12]

Public confrontation and legislative elections

The official electoral campaign did not open until three months after the dissolution, on 22 September 1877;[38] but the preceding months were highly agitated politically and this campaign is described as one "of the most vehement" in the history of France.[12]

Official candidacies

In the name of "the struggle between order and disorder", President Mac Mahon personally committed himself to the electoral battle and multiplied trips to the provinces.[22] As early as 9 June, in order to secure the Senate decision on the dissolution of the Chamber, he had reached an agreement with the Legitimists, guaranteeing them numerous constituencies in exchange for their support and pledging to leave power definitively at the end of his septennat.[39] On 3 July, the Duke of Broglie declared that candidates favourable to the head of state could use a white poster bearing the words "Candidat du gouvernement du maréchal de Mac-Mahon", in the manner of the official candidacies of the Second Empire.[39]

In a communiqué, the president defended these candidacies and hinted that he might attempt to resist if the election result were unfavourable to him: "In the event of hostile elections, France would become for Europe an object of distrust. As for me, my duty would grow with the peril. I shall remain to defend, with the support of the Senate, the conservative interests".[40] In his various speeches, Mac Mahon denounced radicalism and accused the left of running the risk of war for the country.[40] He published a new address to the French on 19 September 1877, in which he proclaimed himself in solidarity with the de Broglie cabinet and accused the "363" of wanting a Chamber that would be a replica of the National Convention of 1792.[38]

At the same time, the government multiplied judicial proceedings against newspaper titles or newspaper sellers and the repression by the prefects intensified: nearly 2,000 bars were closed, as well as several Masonic lodges.[39]

- One of Mac Mahon's trips (here to Bourges), as seen by Le Monde illustré, 11 August 1877.

- Posters reproducing the declaration-manifesto of President Mac Mahon to the French people (19 September 1877) and his appeal to vote (12 October 1877).

- Electoral propaganda brochures glorifying Mac Mahon, anti-Gambettist pamphlet courting the radical electorate and other conservative libels against the “363”.

Unity of the republicans

Faced with the president's official candidates, the republicans displayed their unity. Adolphe Thiers and Léon Gambetta proved the most combative. Republican newspapers launched subscriptions, increased their circulation and relied on railway workers and commercial travellers to ensure distribution throughout the country. An electoral committee was created, composed of 18 deputies representing all republican tendencies, from Georges Clemenceau to Jules Ferry, and other committees were created on the same model at the level of each canton.[39]

- “Salut aux grands citoyens !”, tribute by the caricaturist J. Blass to the republicans Victor Hugo, Louis Blanc, Léon Gambetta and Adolphe Thiers (L'Éclair, No. 9, 19 August 1877).

- The caricaturist André Gill published the periodical Le Bulletin de vote to make known the portrait and biography of the republican candidates (here Georges Clemenceau) during the 1877 legislative campaign[41][42]

- The chocolate manufacturer industrialist Émile-Justin Menier financing the republican electoral campaign to the tune of 100,000 francs. Illustration by André Gill, La Lune rousse.

- A "convinced wife" forces her husband to swallow chocolate as compensation for the generous donation made by the Menier company in favour of republican candidates. Caricature by Cham, Le Monde illustré, 22 September 1877.

To finance their campaign, the republicans relied on numerous personalities, notably the owner of the department store Le Bon Marché, Aristide Boucicaut, the chocolate-making patronal dynasty of the Menier, the banker Henri Cernuschi or the financier Emmanuel-Vincent Dubochet, who placed his private mansion at Gambetta's disposal.[39]

The latter delivered a speech in Lille on 15 August 1877 whose peroration has remained famous. Acclaimed by the audience, he declared to the president and his supporters: "When France has made her sovereign voice heard, believe it well, gentlemen, it will be necessary to submit or resign".[39][40] This formula was immediately reprinted in La République française and the Council of Ministers decided to prosecute the speaker, who was no longer protected by parliamentary immunity, and his newspaper, for insulting the head of state.[39] This decision was criticised even in the conservative camp, which feared that the trial would give too much publicity to the republican candidate. Gambetta, tried in absentia on 11 September by the correctional tribunal of the Seine, was sentenced to three months in prison and a fine of 2,000 francs. Confident of his re-election, he immediately appealed, the second judgment being able to take place only after the ballot.[39]

The death of Adolphe Thiers on 3 September was exploited by the republicans, the "363" gathering around the family of the deceased during the funeral which no official attended on 8 September. This sudden disappearance, however, tempered the optimism of the republicans who had envisaged the return of Thiers to the presidency of the Republic in the event of electoral victory and resignation of the marshal. It was the name of Jules Grévy that replaced it, despite the disagreements that persisted between the latter and Gambetta.[43] At the end of September, François-Auguste Mignet published a posthumous manifesto by Thiers in which the former president recalled the absolute necessity of the Republic to avoid civil war.[38]

- Léon Gambetta at the funeral of Adolphe Thiers, 8 September 1877. Illustration published in The Graphic.

- The shade of Thiers brandishes his manifesto from beyond the grave to exhort Mac Mahon to maintain the republican regime but the marshal sticks to his own presidential manifesto.

Involvement of business circles

In the early years of the Third Republic, the influence of business circles in the political game was considerable: on the one hand, the country's economic recovery required close collaboration between political power, high finance and credit institutions; on the other hand, business circles were largely over-represented among political personnel, precisely among the centre right and centre left groups that made up most of the ministerial cabinets of this period.[44] Just as several ministers of the Broglie cabinet were closely associated with the economic world[note 1], numerous members of the centre left held seats as directors in the largest companies in the key sectors of the French economy, particularly banks, railways, mining and metallurgy.[44] The latter, in addition to their financial power, had all the greater influence because they controlled numerous titles in the liberal press. Although these newspapers could not claim high circulation[note 2], their impact was decisive on the evolution of the regime insofar as they were read not only by politicians but also among economic decision-makers, bankers, stockbrokers or major industrialists.[44]

In the aftermath of 16 May 1877, part of the business community, particularly high finance and the major financiers orbiting the Rothschild Bank, welcomed with satisfaction the appointment of the moral order cabinet of the Duke of Broglie, and the weeks following President Mac Mahon's initiative were marked by relative stock market stability. However, most economic elites clearly committed themselves in favour of the 36 Republican candidates because they considered the coup of the Seize Mai as "a factor of disorder contrary to the smooth running of the economy". The Journal des débats referred in this regard to "an eloquent lesson in political immorality".[44] Throughout the campaign, the liberal press echoed the concern of business circles about the economic slowdown caused by the presidential coup, after several years of calm and prosperity, and many of their representatives provided material and financial support to the republicans. For example, Léon Say offered 25,000 francs for the formation of the Left Electoral Committee, while major entrepreneurs such as Jean Dollfus, Alfred Koechlin-Schwartz or Camille Risler sat on local electoral committees.[44]

Conversely, police reports indicated that the banker Alphonse de Rothschild, promoted to the rank of Commander of the Legion of Honour on the proposal of Minister Eugène Caillaux on 18 July 1877, in the middle of the electoral campaign, had financed the conservative camp's campaign to the tune of 2,5 million francs.[44]

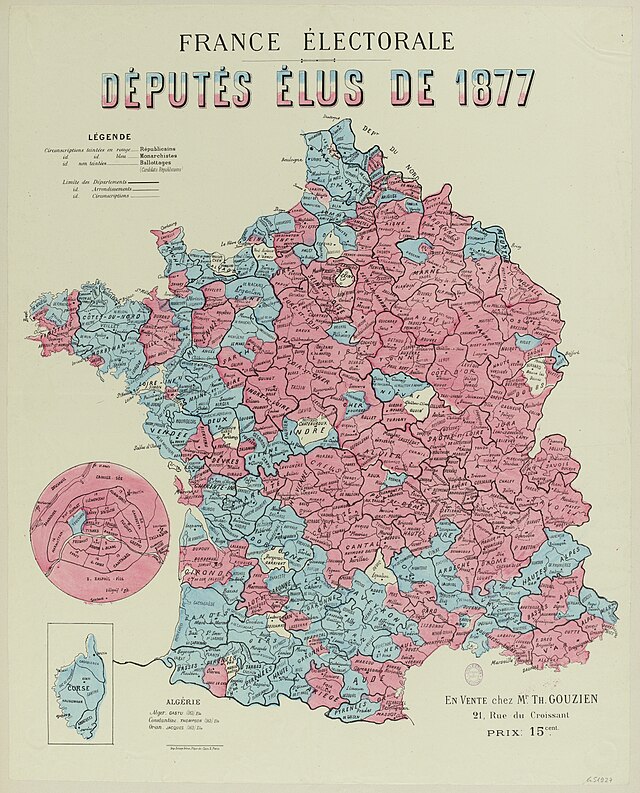

Results of the elections (14–28 October)

It was not until 22 September 1877 that the Council of Ministers set the legislative elections for 14 October and the meeting of the Chamber for 7 November.[38] In the first round, only 15 of the 531 constituencies remained unfilled. The victory of the republicans was undeniable, but it did not have the scale anticipated: they then counted only 321 elected, far from the 405 predicted by Gambetta a few weeks earlier. In a letter addressed the next day to Princess Lise Troubetzkoy, the latter denounced the "threats of corruption, excesses of all kinds, overturned ballot boxes, bought and falsified votes, in short more odious acts committed in three months than the Empire had perpetrated in twenty years" .[45] In reality, the progress of the conservatives, who gained 50 seats, was explained mainly by the mobilisation of their electorate, with abstention falling from 25% in the 1876 elections to less than 20% in 1877.[45]

In the second round, on 28 October, the conservatives won 11 seats more, and although the republicans ultimately had a large majority, with 323 elected, they led the right by just under 800,000 votes.[45] The Bonapartists, who rose from 76 deputies to 104, formed the largest opposition group in the new Chamber, and while the number of Legitimists also increased, from 24 deputies to 44, the Orléanists were in sharp decline, from 40 to 11 elected: the "parliamentary right", which had agreed to compromise in the Constitutional laws of 1875 and establish the Republic, was defeated.[12]

- Crowd on the Boulevard des Italiens reading the election results in the newspapers, 14 October 1877. Engraving by Auguste Trichon published in L'Univers illustré, 20 October 1877.

- "A false joy", Boulevard Montmartre: the newspaper La France erroneously announces the electoral defeat of Oscar Bardi de Fourtou in Ribérac. Drawing by Félix Régamey published in The Illustrated London News, 20 October 1877.

- After the elections, France dons the attire of the Republic while putting away the clothes of the "costumier" Mac Mahon. “A Decided Preference”, caricature published in Punch, 27 October 1877.

Decisive struggle

Mac Mahon's last attempts at resistance (October–December)

As soon as the election results were known, President Mac Mahon considered resigning, urged in this direction by some of his close associates such as his secretary Emmanuel d'Harcourt, but he gave up the idea.[46] The de Broglie government, disavowed at the polls, remained in place pending the cantonal elections of 4 November.[47] In the meantime, Mac Mahon multiplied consultations and considered dissolving the Chamber of Deputies once again, but such a decision would sound like a rejection of the nation's verdict.[48] Furthermore, the President of the Senate, Gaston d'Audiffret-Pasquier, informed him that, this time, the upper chamber would not give its agreement and advised him to accept a parliamentary government.[47][49] Mac Mahon also considered forming a "military cabinet"[50] under the direction of the conservative senator Augustin Pouyer-Quertier,[47] entrusting the War portfolio to General Félix Charles Douay and the Interior to General Auguste-Alexandre Ducrot, but he ultimately rejected this possibility, thus renouncing bringing the army onto the political scene in this way.[50]

Unable to form a new government, the president asked on 6 November the ministers of the de Broglie cabinet to withdraw their resignations, to which the republican deputies responded by demanding the invalidation of all deputies elected with the presidential white poster and the indictment of the ministers.[51] On 10 November, they declared the Chamber constituted[35] and two days later re-elected Jules Grévy to its presidency, while his brother Albert Grévy proposed the creation of an inquiry commission on illegal acts committed since 16 May. Composed of 35 deputies, it was accepted by 312 votes to 205 and appointed on 14 October.[51][35] The Duke of Broglie sought the Senate's support to reject the commission, but Audiffret-Pasquier informed him that, since a decision to create an inquiry commission was not a law, the upper chamber could not oppose it. The de Broglie cabinet finally submitted its resignation on the evening of 17 November.[51]

At an impasse, Mac Mahon appointed one of his close associates to the presidency of the Council, General de Rochebouët.[50] No parliamentarian was a member of this cabinet which, in the president's mind, was nothing other than a "business ministry" whose sole mission was to handle current affairs.[52][50] The Chamber of Deputies responded immediately by voting a motion of no confidence against a cabinet which, in its eyes, "is the negation of the rights of the nation and of parliamentary rights".[53] This motion was largely accepted, by 325 votes to 208, but the government refused to resign. The tension increased all the more as rumours of a coup d'État spread.[50][53]

Batbie project and rumours of a coup d'État

The anger of the republicans redoubled when the president considered the appointment of the Orléanist senator and former minister Anselme Batbie.[53] The choice of this new conservative government against the republican majority appeared as the president's last attempt to recover his authority and took on the appearance of a real coup d'État.[48] Once appointed President of the Council, Batbie would have proclaimed the state of siege, had the republican leaders arrested, levied taxes by decree, organised new elections and a plebiscite.[54] The implementation of this project took shape around 27 and 28 November[55][48] and rumours spoke of a summons to Paris of the army corps commanders for 10 December, General de Rochebouët having ordered them to stand ready.[48]

The project ultimately failed. On the one hand, the prospective ministers were divided on the question,[53] the conservative press was mostly in favour of the president's submission and many of his supporters, attached to parliamentary liberalism, refused to contemplate the violation of the rights of the Chamber: the presidents of the Senate and of the Chamber of Deputies, Audiffret-Pasquier and Jules Grévy, took measures to protect the assemblies and met with the prefect of police Félix Voisin. On the other hand, the army's support for a coup d'État was by no means guaranteed. Since 1872, with its ranks based on conscription, republican sentiment had been growing among the military as it took root in the French population.[48] In 1877, about 50% of the generals were monarchist in opinion against 39% liberals and republicans, and the proportion was reversed among the colonels with 36.5% monarchists against 45.5% republicans or liberals.[56] At the beginning of December, Léon Gambetta met with General de Galliffet to ensure his support for the republic, and several generals spontaneously placed themselves at his disposal, such as Justin Clinchant, Jean-Baptiste Campenon or Jean-Joseph Farre.[48]

Faced with the impossibility of forming a cabinet to his liking, Mac Mahon considered resigning but his close associates dissuaded him again, both to protect themselves and to avoid a total victory for the republicans.[53]

- Caricatures of Mac Mahon by John Tenniel, published in Punch.

- Mac Mahon bogged down in the mud of Legitimism, Bonapartism and clericalism (Punch, 3 November 1877).

- Marianne scolds Mac Mahon: "I intend to be the mistress in my own house. You will execute my orders or you will leave!" (Punch, 17 November 1877).

- Who will step over the Constitution? Tug of war between Marianne and Mac Mahon under the eye of crowned raptors, allegory of the trial of strength between the republicans and the President of the Republic (Punch, 8 December 1877).

Mac Mahon submits (13 December)

On 13 December 1877, President Mac Mahon finally submitted to the election results and recalled Jules Dufaure to form a government dominated by moderate republicans of the centre left but which also included some close to Gambetta such as Charles de Freycinet at Public Works. Gambetta also imposed the presence of William Waddington at Foreign Affairs, despite the reservations of the head of state who was consulted only for the War portfolio, awarded to his former aide-de-camp Jean-Louis Borel, the only apolitical and conservative member of the new cabinet.[57][58] Other close associates of the president were removed from their responsibilities: the prefect of police was dismissed as was Mac Mahon's chief of staff, Emmanuel d'Harcourt, who, at the request of the republicans, had no replacement. Finally, General Ducrot, whom the deputies accused of having too openly conspired in favour of a coup d'État, was relieved of his command of the 8th Army Corps.[35] The next day, the President of the Republic addressed a message to parliament that sounded like a political capitulation.[16] Mac Mahon first acknowledged that dissolution could not be a normal way of governing a country and concluded by saying: "The Constitution of 1875 founded a parliamentary Republic by establishing my irresponsibility, while instituting the joint and individual responsibility of the ministers. Thus are determined our respective duties and rights. The independence of the ministers is the condition of their responsibility. […] These principles, drawn from the Constitution, are those of my government".[59] For the historian Jean-Marc Guislin, "The hesitations and divisions of the conservatives, the hostility of business circles and the reluctance of the army led the Marshal to submit. He also encountered the firmness and resolution of the country won over to the Republic".[35]

- “La Grande Retraite de 1877”: Pépin caricatures the political failure of the monarchists as a military debacle reminiscent of Napoleon (Le Grelot, 30 December 1877).

- Portrait of Jules Dufaure, recalled to the presidency of the Council.

Remove ads

Consequences of 16 May

Summarize

Perspective

Republic of the republicans

Control of the institutions

In his statement to the Chamber, President Mac Mahon turned towards the future and affirmed that "the end of this crisis will be the starting point of a new prosperity".[60] On 24 January 1878, the Chamber adopted by 313 votes to 36 the amnesty law for offences and misdemeanours committed from 16 May to 14 December 1877, an appeasement law proposed by the government and which, according to its rapporteur René Goblet, allowed "to repair the disorders committed by the 16 May".[35]

The Universal Exhibition, inaugurated on 1 May 1878 in Paris and which attracted nearly six million visitors, was intended to show the recovery of France and its nascent Republic to the eyes of the world, while parliamentary work was suspended so as not to give a spectacle of division.[60] Supported by Gambetta, the President of the Council Jules Dufaure showed pragmatism to reassure public opinion as well as the political class and his government initiated major projects such as the Freycinet Plan, a vast public works programme that won strong support.[60]

The definitive break between Mac Mahon and the republicans nevertheless occurred over the question of the purge of the army administration, demanded by Jules Ferry and Gambetta. The president was also indignant when the minister Émile de Marcère presented for his signature a decree providing for the revocation, transfer or retirement of 82 mayors.[62]

At the same time, the republicans continued their progress: the Chamber itself invalidated 70 elections on the pretext of clerical or political pressure and, following the by-elections, their number of deputies approached 400. On 5 January 1879, the republicans also won the Senate elections, the logical consequence of their victory in the municipal elections of 1877,[1] and obtained the majority in the upper chamber. The president, deprived of all institutional support, preferred to resign on 30 January 1879 after refusing to sign the decree removing command from about ten generals. Jules Grévy replaced him the same day.[63][62]

With the election of the latter, the republicans now dominated all components of power. Elected to the presidency of the Chamber, Léon Gambetta exhorted the deputies: "We can, we must all, at the present time, feel that the combats have had their day. Our Republic, finally emerged victorious from the melee of parties, must enter the organic and creative period".[35]

- The days of the anti-republican Senate are numbered. Caricature by Pépin, Le Grelot, 17 March 1878.

- The adversaries of the Republic are forced to don the Phrygian cap to pay their share. Caricature by Pépin, Le Grelot, 31 March 1878.

- Marianne looks with satisfaction at the 363 returning to the Chamber of Deputies. Caricature by Pépin, Le Grelot, 17 May 1878.

- Jules Grévy reading the resignation letter of Mac Mahon from the rostrum of the Chamber, 30 January 1879.

Total victory of the republicans

While the historian Odile Rudelle speaks of the "absolute Republic" to describe the years that mark the definitive conquest of the regime by the republicans, Vincent Duclert calls it the "Republic of the republicans" .[64]

For the philosopher Jacques Bouveresse, the 16 May crisis is not a mere constitutional debate but the consecration of the republican conception of the future which consists not only in founding a new constitutional regime, but in laying the foundations of a new society. From his point of view, the events of 1877 made it possible to "seal the great republican alliance between the bourgeoisie, its rural allies, the labour movement and its sympathisers" symbolised by the funeral of Adolphe Thiers in September: "the labour movement and the extreme left now accept the government of the conciliatory centre, of the republicans grouped around Gambetta, in exchange for amnesty and, in the longer term, very long term, human and social progress", even if that means allying with the successors of Thiers, who had "repressed the Commune with unheard-of ferocity". President Mac Mahon then appears as a scapegoat whose moral order government and dualist reading of the Constitution amount to an "irremissible crime against democracy", far more than the massacre of the Communards during the Bloody Week.[65]

Ultimately, the resolution of the crisis without violence or transgression of legality demonstrates the "pacification" of French political life that results from the rooting of parliamentary liberalism in the country and President Mac Mahon's initiative can be seen as the authoritarian act of a head of state to try to recover the power that was his in a hierarchical society, organised by religion and governed by a king. As the historian Jean-Marie Mayeur points out, 16 May coup reflects the desire of the "elites of old France" to preserve their influence and that of the Church on society at the expense of the promotion of "the new layer".[66] The presidential initiative is therefore only a last gasp of tradition to resist modernity, and Mac Mahon's submission on 13 December, in the continuation of the republican successes in the legislative elections of 1876 and 1877, testifies to the strength acquired by the Republic, "henceforth synonymous with legality".[48] The historian Raymond Huard considers that from this date, "the shadow of the 2 December was thus tending to fade".[67]

In the months following the president's submission, the appeasement advocated by Gambetta and desired by a large majority of the political class materialised in the abandonment of proceedings against the ministers of the 17 May cabinet, a measure approved by the Chamber at the request of the new President of the Council William Waddington in March 1879. The triumphant Republic celebrated its victory through a series of laws aimed at uniting the French: on 14 February 1879, La Marseillaise became the national anthem; the return of the Chambers to Paris was adopted on 21 June and became effective in November; finally, the following year, 14 July was declared the national holiday and the amnesty of the Communards was promulgated.[35]

Order changes sides

In a country where social fear is no longer present, where the economy is prospering and where universal suffrage has enabled the politicisation of the masses, the possibility of a coup de force is rejected by the majority of the French ,[68] so that the disruptive effect introduced by President Mac Mahon's initiative made the fear of disorder work against the camp of conservation according to the analysis of Jean-Marie Mayeur.[69]

The republicans who, traditionally, embodied the threat of disorder, now benefit from popular support and present themselves as guarantors of the institutions, even though their most radical adversaries threaten to use force against them.[48] According to Jérôme Grévy, "so as not to risk destroying their image as a governmental party patiently built over six years, the republicans must refuse any temptation of violent action, even if they are sure of their right".[70] Throughout the period, they distinguished themselves by the calm, resolution and determination they displayed, and as early as 16 May, Gambetta warned his political family against any untimely outburst.[35]

Respect for legality and the Constitution ultimately being shared by President Mac Mahon, the risk of escalation was definitively ruled out, all the more so since the marshal's supporters were divided, as Jean-Marc Guislin reports:[35]

The tensions within the moral order coalition are manifest […] : disappointment of the clericals and legitimists whose wishes are hardly taken into account, fear of the Orléanists in the face of the dynamism and authoritarian methods of the Bonapartists, oppositions on the appropriateness of the dissolution, the date of the elections, the choice of candidates, resistance or submission.

The 16 May 1877 crisis thus testifies to the reversal of political fronts. During the electoral campaign, the major titles of the liberal press such as La Semaine financière and the Journal des débats relayed the concern of business circles and associated the moral order with disorder, while praising the Republic as a guarantee of stability.[44] From the early days of the crisis, the republicans presented the conservative manoeuvres as a peril for the country, as shown by Victor Hugo's intervention during the Senate discussion of the conforming opinion on the dissolution:[48]

The government is committing this imprudence: the opening of the unknown. An arrest of civilisation in the full 19th century is not possible. I vote against the catastrophe, I refuse the dissolution.

The republicans also denounced the risk of war that a clerical policy would entail, in reference to the threats that Chancellor Bismarck had uttered in 1873 when he stated that France's political alignment with the Vatican would make her Germany's sworn enemy.[71]

Religious question

It was over a question of a religious nature that the crisis broke out at the beginning of May, with the republicans denouncing the pressures of the Church, long accused of being favourable to a monarchical restoration, and the period ultimately reinforced the antagonism between the two camps.[23]

Although some ecclesiastics, such as the Bishop of Orléans Félix Dupanloup, elected senator by a narrow margin the previous year and whose influence was significant with President Mac Mahon,[72] would have wished for the formation of a cabinet more conservative than the de Broglie government, they largely supported the electoral campaign of the president's official candidates, notably through press organs such as La Défense religieuse et sociale, the newspaper of Bishop Dupanloup.[23]

While the episcopate remained largely in the background, many priests engaged in a most virulent campaign.[23] The historian Arnaud-Dominique Houte reports that foreign caricaturists then took to representing Mac Mahon as a puppet manipulated by priests.[72]

This intrusion of the clergy into the electoral campaign tended to reinforce the anticlericalism of the republicans, with the argument of clerical intervention moreover regularly put forward by the latter to justify the invalidation of certain elections.[23] After the president's submission, the appointment of a Protestant to Foreign Affairs in the person of William Waddington demonstrated the republican desire to provide a guarantee of neutrality in diplomatic affairs regarding religious matters.[35]

- Anticlerical caricatures targeting Marshal Mac Mahon.

- Wearing a skullcap, Mac Mahon kneels before a Jesuit and the Legitimist pretender Henri, Count of Chambord. In the background, a gagged Léon Gambetta. “It was in 1877”, lithograph by Henri Rupp after a composition by Achille Belloguet.

- Protecting Marianne, a man of the people tramples a comminatory government decree and the Syllabus of Errors. With his right hand, he shakes Mac Mahon whose bicorne and broken sabre lie on the ground. “Anger of the People”, drawing by A. Belloguet.

- Marianne and Léon Gambetta (depicted as a sans-culotte) tip over the sedan chair of the pope and Mac Mahon, who here suffers “another Sedan”. Caricature by Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly, 10 November 1877.

Consequences of triumphant parliamentarism

Ministerial instability

The historian Jean-François Chanet considers that the Seize Mai marks the transition between two eras of French democracy.[73] After his election to the presidency of the Republic in 1879, Jules Grévy declared to the assemblies that he never wished to enter into conflict with the national will expressed through its constitutional organs: he thus renounced the use of the right of dissolution, which de facto placed the executive, and in particular the government, under the control and domination of the legislative power.[1] The president remained an influential figure but devoid of real powers.[12] The Third Republic then slid from a dualist parliamentarism to a monist parliamentarism, in other words a regime of assembly, which ratified the customary drift of the presidential function according to the constitutionalist Éric Ghérardi.[1]

Grévy's election was supposed to mark for the republicans the beginning of an era of stability thanks to a Constitution "tested by trials of grand style, especially by that of the Seize Mai" according to the expression of Maurice Reclus,[74] but it ultimately led to the opposite situation and, for Jean-François Chanet, "the hemicycle of the Palais Bourbon remained a battlefield where the corpses of ministries were no longer counted".[73] The historian Odile Rudelle speaks of an abusive preponderance of parliamentary representation over the will expressed by the electorate[75] that the republicans accepted all the more as ministerial instability appeared to them as a virtue against the authoritarian temptation of a head of state whose powers would be extended.[73] In his work Propos d'un Normand, published in 1912, the philosopher Alain describes precisely the mechanism of vigilant mobilisation of the "citizen against the powers":[73]

Since the 16 May we have not a single example of even sketched resistance. One can even say that ministries are increasingly fragile in the face of unfavourable opinion; they no longer even wait for a vote; as soon as their authority is doubtful, and depends on a shift of a few votes, they leave.

Rejection of the right of dissolution

Thus the Seize Mai led to the weakening of the executive power in favour of the legislative power and, in French political culture, it became "a symbolic date and a reference for subsequent republican defence struggles".[66] The right of dissolution, although enshrined in the constitutional texts and maintained by the republicans during the revision of August 1884,[73][76] became after the Seize Mai and for several generations of politicians the symbol of an authoritarian danger. The socialist Léon Blum called it a "legalised coup d'État"[48] while the lawyer and former minister César Campinchi popularised the expression "As long as Mac Mahon is dead, the Chamber will not be dissolved" to express the concerted refusal of its use.[77] Retained in the Constitution of the Fourth Republic, the right of dissolution remained theoretical until the President of the Council Edgar Faure resorted to it on 29 November 1955 to resolve the crisis opened by the overthrow of his ministry.[73] Largely approved by the French population, this dissolution was widely criticised in the political camp, particularly by Pierre Mendès France and the members of the SFIO, to the point of leading to the expulsion of Edgar Faure from the Radical Party, and it was only under the Fifth Republic, starting with the dissolution of 9 October 1962 decided by President Charles de Gaulle to resolve the conflict with the National Assembly on the question of the election of the head of state by universal suffrage, that parliamentary dissolution ceased to be considered an anti-republican act.[73]

Remove ads

Historiography

Summarize

Perspective

Studies

Despite the fundamental role of the 16 May crisis in the definitive advent of the Republic, its historiography is sparse.[78][21] While the Seize Mai is frequently mentioned in general works devoted to the early years of the Third Republic, by historians such as Daniel Halévy, Odile Rudelle, Jérôme Grévy or Jean-Marie Mayeur, as well as in biographies devoted to its protagonists, it is rarely the subject of a detailed study.[66] In 1965, Fresnette Pisani-Ferry published with Éditions Robert Laffont, Le coup d'État manqué du 16 mai 1877, while on 16 November 2007, under the direction of Jean-Marc Guislin, a study day was devoted to it at University of Lille III.[78] According to the historian Guy Thuillier, the small number of studies on the crisis and its origins is partly explained by the relative discretion of its protagonists: Jules Simon, in his memoirs entitled Le Soir de ma journée, practically evades the question, President Mac Mahon gives only an official version of it, and the Duke of Broglie does not address the subject at all in his Souvenirs.[79]

Numerous articles and chapters in university works are nevertheless devoted to it. In 1986, Michel Winock provided a detailed account in his narrative of the political crises of contemporary French history, La fièvre hexagonale,[78] and the same year, Guy Thuillier devoted a short thirteen-page study to its possible origins.[79] Two years later, the sociologist Willy Pelletier spoke on the question at a colloquium devoted to the presidential institution.[66] In 2002, in a work devoted to electoral incidents from the French Revolution to the Fifth Republic, Jacqueline Lalouette studied more precisely the wave of invalidations following the 1877 legislative elections, while in 2004, the jurist Jean-Pierre Machelon questioned the relevance of likening the Seize Mai to an attempted coup d'État.[66] On another level, historians such as Bernard Ménager or Marcel Vigreux address in detail the direct consequences of the 16 May crisis in works devoted to local history, namely political life in the Nord department for the former or relations between peasants and notables in the Morvan for the latter. In 2002, Jean-Marc Guislin studied the event more particularly through the career of the minister Auguste Paris whose abundant correspondence with his wife he analyses.[66] Studies devoted to the Seize Mai also go beyond the national framework: the American historian Susanna Barrows devoted several texts to it that highlight "the original approach of the generation of American historians of France to which she belonged compared to French historians and justifies the project of a social history of the rejection of authoritarian power through the prism of France of 16 May 1877".[78]

Retained date

Jacqueline Lalouette and Jean-François Chanet recall that the "Seize Mai" is one of the rare events in French history that can be designated by a date immediately intelligible, without the year being specified, like the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, the coup d'État of 18 Brumaire carried out by Napoleon Bonaparte or the proclamation of the Republic on 4 September 1870.[21][73]

But whereas this "phenomenon of memorial crystallisation" was caused by revolutionary days or coups d'État carried out under popular pressure, it applies in the case of the Seize Mai to a change of government decided by the executive power and without consultation of the assembly, in the manner of the message of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte to the National Legislative Assembly to announce the formation of an "extraparliamentary" ministry on 31 October 1849. These two events are perceived as exceptional, that is to say that they mark "refer to a turning point in political life sufficiently identifiable without the need to indicate the precise date" according to Jean-François Chanet.[73] According to the latter, it is for this reason that the date of 16 May is retained to designate the entire process triggered by the initiative of President Mac Mahon and not that of the dissolution, the legislative elections or his final submission, because "the anomaly thus designated is therefore no longer the irruption of illegality or violence into the ordinary course of political life […] but the doubtful legitimacy, the ill-considered choice, the untimely abruptness of an action that came to disrupt the regular functioning of the institutions adopted less than two years earlier".[73]

All historians agree in recognising the importance of the Seize Mai in the political and institutional history of the country. For Philippe Levillain, this crisis "is part of the republican annals". He specifies that, "intended and experienced as a decisive trial of strength on the definition of conservatism, it had cascading consequences on republican mentalities and its effect was considerable on the behaviour of the rights".[80] Jean-Marc Guislin for his part describes it as a "neuralgic" period.[66]

Coup d'État hypothesis

Atmosphere of a coup d'État

In 1877, the Third Republic was still living under the royalist threat and in the memory of the 2 December 1851 coup d'état, so that, for the republicans, "the holders of executive power are in principle suspected of seeking to increase their prerogatives to remain in power".[48] It is for this reason that "French historiographical and political tradition has made the Seize-Mai the threat of a coup d'État", as the historian Claude Nicolet asserts.[81] In many respects, the course of events in 1877 indeed reproduced the process of 1851 that led to the establishment of the Second Empire and the republican historiography that immediately took shape imposed for a vision of the Seize-Mai as a coup de force intended to bring down the Republic.[48]

By obtaining the resignation of a ministry nevertheless invested with the confidence of the Chamber of Deputies and, consequently, of the nation that had elected it, President Mac Mahon gave the impression of practising "a legal coup d'État":[81] "the presidential act could seem a violation of the national will and the affirmation of an authoritarian and personal conception of the institutions", according to the analysis of Emmanuel Cherrier.[48] In the letter he addressed to Jules Simon, Mac Mahon placed his responsibility before the country as superior to that of the government before the Chamber, thus taking up "the logic of the Louis-Napoleonic argument" of 1851 by opposing the formal legality of the Constitution and the legitimacy of the head of state as representing the nation as a whole.[48] More than the coup d'État of 2 December, Mac Mahon's initiative recalled the dismissal in October 1849 by President Bonaparte of the Barrot government, invested with the confidence of the National Assembly, and its replacement by the Hautpoul government favourable to him.[48] Furthermore, Thierry Truel affirms that the speed with which the Broglie cabinet was formed suggests that the president's coup de force was premeditated.[82]

From the opening of the crisis, Jules Ferry presented it as the struggle "of the government of the President of the Republic against parliamentary government", so that the historian Michel Winock saw the presidential initiative as an abuse of power "exercised against universal suffrage and the Republic".[83] In 1877, the atmosphere of a coup d'État was all the more perceptible because the Bonapartists explicitly invited the president to take action, as evidenced by the articles of Paul de Cassagnac in Le Pays which demanded the state of siege and exceptional laws.[48] Mac Mahon himself, in his statements, reinforced the ambiguity of the situation. On 1 July, in a speech before the army, he affirmed: "You will help me, I am certain, to maintain respect for authority and the laws, in the exercise of the mission that has been entrusted to me and that I will fulfil to the end", then on 1 October, he proclaimed: "I cannot obey the summonses of demagogy. I cannot become the instrument of radicalism, nor abandon the post where the Constitution has placed me".[84] Furthermore, the appointment of authoritarian Bonapartists such as Fourtou to the Interior, the revocations of elected officials or magistrates, and the dissolution of municipal councils were immediately denounced as "the return of the tyrannical acts of the Empire".[48]

Constitutional legality of the presidential initiative

However, the course of the 16 May crisis presents no character of illegality or violence, two criteria determining the notion of coup d'État.[85][48] In the first place, as Emmanuel Cherrier notes, "physical violence is nowhere and at no time employed, and there is no seizure of power by force or the threat of force, no troop movements nor arrest of republican leaders".[48] On the other hand, all the presidential and governmental acts of the period are established within the limits strictly defined by law.[48] As Thierry Truel notes, "most of the dispatches sent to the prefects [...] are intended to remind them of the legal frameworks within which they can act, without falling under the blade of possible legal actions brought by republican opponents".[86]

The crisis results above all from a difference in interpretation of the constitutional laws which still retained a certain ambiguity in 1877.[87] If President Mac Mahon considers that the government bound to share his views, the republicans believe it is responsible only to the chamber elected by direct universal suffrage and which expresses the will of the nation, as opposed to the Senate designated by grand electors and the president elected indirectly by parliamentarians.[48]

For Emmanuel Cherrier, "the Seize-Mai is therefore also a controversy as to the monist or dualist responsibility of the government". Nothing then obliged Jules Simon to resign since nothing expressly indicates the slightest responsibility of the government to the head of state in the constitutional laws of 1875, and the decision of the President of the Council results only from the prevalence of a dualist reading of the Constitution and the "à la française" practice of the parliamentary regime which customarily establishes the dual responsibility of ministers.[48] The letter addressed by Mac Mahon therefore has no unconstitutional character, and even more, the president does not feel he is carrying out a coup d'État by taking this initiative: since it is up to him to appoint ministers, he believes he can also revoke them outright.[48] Furthermore, the administrative pressure exerted by the Broglie cabinet until the legislative elections does not exceed the framework of the law: the transfer or revocation of officials is part of the powers available to the government, as is the suspension of municipal councils or the revocation of mayors, guaranteed by the laws of 14 April 1871 and 20 January 1874.[48] In addition, while the law of 27 July 1849 subjects the peddling of newspapers and printed matter to prefectural authorisation, that of 29 December 1875 defines the referral of press offences to the correctional court, so that the censorship exercised by the government is also carried out by applying legal provisions.[48]

For Emmanuel Cherrier, the 16 May crisis is therefore a paradoxical event: "1877 has the particularity of not being a coup d'État but of appearing as such to the republicans of the time, without even mentioning those, revanchist Bonapartists or determined royalists, who regretted that it was not one". By qualifying the action of President Mac Mahon as a coup d'État, the republicans sought above all to discredit him in the eyes of public opinion.[48]

Remove ads

Seize Mai in arts and culture

Summarize

Perspective

Literature

With the corpse of an imperial eagle at his feet, Victor Hugo rises as a judge to write Histoire d'un crime. Censorship prohibited the publication of this admiring drawing by André Gill for La Lune rousse of 7 October 1877.[88][89]

It was in the context of this crisis that Victor Hugo had his Histoire d'un crime published,[90] a text mainly written in Brussels where the author had taken refuge the day after the coup d'État of 2 December 1851 and of which only the most pamphletary part was published as early as 1852 in the form of a book of about a hundred pages, Napoléon le Petit.[91] Three days after the coup of 16 May, La Revue politique et littéraire announced that the writer was working on a Histoire du coup d'État to appear in October and simultaneously in French, English, German and Italian.[92] From then on, while preparing the edition of his work, Victor Hugo led the fight in the Senate where he organised two meetings a week with left-wing senators and where he delivered a virulent speech against the dissolution.[92]

The first volume of Histoire d'un crime appeared on 1 October, two weeks before the first round of the legislative elections,[91] and achieved great commercial success.[92] The sentence that the author placed as an epigraph to his work sums up the pedagogical and propagandist role he intended to assign to this publication: "This book is more than topical: it is urgent. I publish it".[91]

In this account, the writer warns his reader against a probable and prophetic return of a coup d'État, assimilating the one carried out by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte twenty-six years earlier to establish the Empire to the initiative of President Mac Mahon. Moreover, the account does not end the day after 2 December but at the end of the French defeat at Sedan in 1870, Victor Hugo thus seeking to recall the role deemed inglorious of Mac Mahon during this rout while denouncing the responsibility of the emperor and the risk of war that a new advent of this regime would entail.[91] Certain passages of the work are reprinted in republican newspapers but also conservative, monarchist or Bonapartist ones, each seeking to derive the best profit from it.[91]

Other renowned writers refer to the Seize Mai crisis in their works. This is the case of Charles Péguy in his essay L'Argent in 1913. Evoking the changes in French culture after the end of the Ancien Régime and "the temporary dechristianisation of France", he mentions the event: "There must be a reason why, in the country of Saint Louis and Joan of Arc, in the city of Saint Geneviève, when one starts talking about Christianity, everyone understands that it is about Mac-Mahon, and when one prepares to talk about the Christian order so that everyone understands that it is about the Seize-Mai".[93] In 1919, Marcel Proust mentions it in In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower to describe the talent or opportunism of his character, the Marquis de Norpois, who managed to play an important role before and after this date.[94]

Popular culture

From the beginning of the crisis, the authorities noted an increase in critical inscriptions and graffiti on the walls of major French cities, and the historian Susanna Barrows, who studied this phenomenon precisely, states that the Paris police prefecture files concerning these acts are four times more voluminous for the year 1877 than for any other year after the Paris Commune. She refers to a genuine "clandestine opposition culture" that sought to discredit the conservatives and more particularly President Mac Mahon, sometimes likened to a "pig", mocked for his age or his Irish origins which would make him a traitor to the nation.[95]

These spontaneous acts follow a topographical logic. The historian notes that Parisian graffiti were mainly inscribed in the affluent districts of the city, with the aim of shocking the conservative electorate as much as possible: thus, on 1 October, the number 363, in reference to the republican deputies, was inscribed on the very façade of the Élysée Palace, and three days later, it was reproduced on a large scale on the walls of buildings Rue Saint-Honoré, on the façades of the Bank of France and the Rothschild house. Similarly, a temporal logic was at work because reports of graffiti multiplied around the most significant events of the crisis: the first two weeks of the crisis in May, the legislative elections in October and the first ten days of December, during the period of uncertainty and rumours of a coup d'État that preceded Mac Mahon's capitulation.[95]

Susanna Barrows estimates that "faced with the moral pretensions of the regime, its adversaries took malicious pleasure in denigrating it in a scabrous, often obscene and deliberately immoral manner". The historian sees in this proliferation of gestures or acts of derision a response to the massive purge undertaken by the government which manifests itself in a form of "brief and often scathing joke" where coarse or even scatological humour is often highlighted. Susanna Barrows notes that "the nickname Macmoncon for Mac-Mahon spread. Posters were put up in urinals or whispered at café counters baroque sexual scenarios featuring the president, his wife, high ecclesiastics and monarchist ministers".[96]

On another level, to qualify their adversaries, some republicans coined the word "seizemayeux",[21] which Lucien Rigaud defines in his Dictionnaire d'argot moderne as the "nickname given to officials after 16 May, to the partisans of the reactionary policy of 16 May 1877".[97] The term became established in the political slang of the Third Republic and was embodied after the crisis in the character of Oscar Seizemayeux, a little hunchbacked, one-eyed and toothless man, drawn by the caricaturist André Gill in issue no. 25 of the satirical weekly La Petite Lune. It is inspired by a famous imaginary comic character in the 1830s under the July Monarchy, Mayeux, created by the caricaturist Traviès, and bears the same first name as the Minister of the Interior of the de Broglie cabinet, Oscar Bardi de Fourtou, a figure hated by the entire republican group.[21]

The number of the 363 republicans who signed the manifesto of 18 June immediately acquired great symbolic value, so that propaganda objects were quickly put into circulation. The portraits of the 363 as well as the printed text of the manifesto appear in particular on handkerchiefs, some of which are preserved in the National Archives or at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.[21][98] Furthermore, in 1878, Aristide Bruant composed a song entitled Les 363 ou les vendanges de la République.[21][99]

Remove ads

Notes and references

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads