Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Semiotics

Study of signs From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Semiotics[a] is the study of signs. It is an interdisciplinary field that examines what signs are, how they form sign systems, and how individuals use them to communicate meaning. Its main branches are syntactics, which addresses formal relations between signs, semantics, which addresses the relation between signs and their meanings, and pragmatics, which addresses the relation between signs and their users. Semiotics is related to linguistics but has a broader scope that includes nonlinguistic signs, such as maps and clothing.

Signs are entities that stand for something else, like the word cat, which stands for a carnivorous mammal. They can take many forms, such as sounds, images, written marks, and gestures. Iconic signs operate through similarity. For them, the sign vehicle resembles the referent, such as a portrait of a person. Indexical signs are based on a direct physical link, such as smoke as a sign of fire. For symbolic signs, the relation between sign vehicle and referent is conventional or arbitrary, which applies to most linguistic signs. Models of signs analyze the basic components of signs. Ferdinand de Saussure's dyadic model identifies a perceptible image and a concept as the core elements, whereas Charles Sanders Peirce's triadic model distinguishes a sign vehicle, a referent, and an effect in the interpreter's mind.

Sign systems are structured networks of interrelated signs, such as the English language. Semioticians study how signs combine to form larger expressions, called texts. They explore how the message of a text depends on the meanings of the signs composing it and how contextual factors and tropes influence this process. They also investigate the codes employed to communicate meaning, including conventional codes, such as the color code of traffic signals, and natural codes, such as DNA encoding hereditary information.

Semiotics has diverse applications because of the pervasive nature of signs. Many semioticians study cultural products, such as literature, art, and media, investigating both the elements used to express meaning and the subtle ideological messages they convey. The psychological activities associated with sign use are another research topic. Biosemiotics extends the scope of inquiry beyond human communication, examining sign processes within and between animals, plants, and other organisms. Semioticians typically adjust their research approach to their specific domain without a single methodology adopted by all subfields. Although the roots of semiotic research lie in antiquity, it was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that semiotics emerged as an independent field of inquiry.

Remove ads

Definitions and related fields

Summarize

Perspective

Charles Sanders Peirce and Ferdinand de Saussure helped establish semiotics as a distinct field of inquiry.[2]

Semiotics is the study of signs or of how meaning is created and communicated through them. Also called semiology,[b] it examines the nature of signs, their organization into signs systems, like language, and the ways individuals interpret and use them. Semiotics has wide-reaching applications because of the pervasive nature of signs, affecting how individuals experience phenomena, communicate ideas, and interact with the world.[4]

These applications make it an interdisciplinary field, originating in philosophy and linguistics and closely related to disciplines like psychology, anthropology, aesthetics, sociology, and education sciences.[5] Because most sciences rely on sign processes in some form, semiotics is sometimes characterized as a meta-discipline that provides a general approach for the analysis of signs across domains.[6] It is controversial whether semiotics is itself a science since there are no universally accepted theoretical assumptions or methods on which semioticians agree.[7] Semiotics has also been characterized as a theory, a doctrine, a movement, or a discipline.[8] Apart from its interdisciplinary applications, pure semiotics is typically divided into three branches: semantics, syntactics, and pragmatics, studying how signs relate to objects, to each other, and to sign users, respectively.[9]

Semiotic inquiry overlaps in various ways with linguistics and communication theory. It shares with linguistics the interest in the analysis of sign systems, examining the meanings of words, how they are combined to form sentences, and how they convey messages in concrete contexts. A key difference is that linguistics focuses on language, while semiotics also studies non-linguistic signs, such as images, gestures, traffic signs, and animal calls.[10] Communication theory studies how individuals encode, convey, and interpret both linguistic and non-linguistic messages. It typically focuses on technical aspects of how messages are transmitted, usually between distinct organisms. Semiotics, by contrast, concentrates on the meaning of messages and the creation of meaning, including the role of non-communicative signs.[11][c] For example, semioticians also study naturally occurring biological signs, like disease symptoms, and signs based on inanimate relations, such as smoke as a sign of fire.[13]

The term semiotics derives from the Greek word σημειωτική (semeiotike), originally associated with the study of disease symptoms.[14] Proposing a new field of inquiry of signs, John Locke suggested the Greek term as its name.[15] The first use of the English term semiotics dates to the 1670s.[1] Semiotics became a distinct field of inquiry following the works of the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce and the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, the founders of the discipline.[2]

Remove ads

Signs

Summarize

Perspective

A sign is an entity that stands for something else. For example, the word cat is a sign that stands for a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. Signs direct the attention of interpreters away from themselves and toward the entities they represent. They can take many forms, such as words, images, sounds, and odours. Similarly, they can refer to many types of entities, including physical objects, events, or places, psychological feelings, and abstract ideas. They help people recognize patterns, predict outcomes, make plans, communicate ideas, and understand the world.[16]

Semioticians distinguish different elements of signs. The sign vehicle is the physical form of the sign, such as sound waves or printed letters on a page, whereas the referent is the object it stands for. The precise number and nature of these elements is disputed and different models of signs propose distinct analyses.[17] The referent of a sign can itself be a sign, leading to a chain of signification. For instance, the expression "red rose" is a sign for a particular type of flower, which can itself act as a sign of love.[18]

Semiosis is the capacity or activity of comprehending and producing signs. Also characterized as the action of signs, it involves the interplay between sign vehicle and referent as organisms interpret meaning within a given context.[19] Different types of semiosis are distinguished by the type of organisms engaging in the sign activity, such as the contrast between anthroposemiosis involving humans, zoösemiosis involving other animals, and phytosemiosis involving plants.[20]

Meaning, sense, and reference

The meaning of a sign is what is generated in the process of semiosis. Meaning is typically analyzed into two aspects: sense and reference.[d] This distinction is also known by the terms connotation and denotation as well as intension and extension. The reference of a sign is the object for which it stands. For example, the reference of the term morning star is the planet Venus. The sense of a sign is the way it stands for the object or the mode in which the object is presented. For instance, the terms morning star and evening star have the same reference since they point to the same object. However, their meanings are not identical since they differ on the level of sense by presenting this object from distinct perspectives.[22]

Various theories of meaning have been proposed to explain its nature and identify the conditions that determine the meanings of signs. Referential or extensional theories define meaning in terms of reference, for example, as the signified object or as a context-dependent function that points to objects.[23] Ideational or mentalist theories interpret the meaning of a sign in relation to the mental states of language users, for example, as the ideas it evokes.[24] Pragmatic theories describe meaning based on behavioral responses and use conditions.[25]

Types and sign relations

Semioticians distinguish various types of signs, often based on the sign relation or how the sign vehicle is connected to the referent.[29] A type is a general pattern or universal class, corresponding to shared features of individual signs. Types contrast with tokens, which are individual instances of a type. For example, the word banana encompasses six letter tokens (b, a, n, a, n, and a), which belong to three distinct types (b, a, and n).[30]

A historically influential classification of sign types relies on the contrast between conventional and natural signs. Conventional signs depend on culturally established norms and intentionality to establish the link between sign vehicle and referent. For example, the meaning of the term tree is fixed by social conventions associated with the English language rather than a natural connection between the term and actual trees. Natural signs, by contrast, are based on a substantial link other than conventions. For instance, the footprint of a bear signifies the presence of a bear as a result of the bear's movement rather than a matter of convention. In modern semiotics, the distinction between natural and conventional signs has been replaced by the threefold classification into icons, indices, and symbols, initially proposed by Peirce.[29]

Icons are signs that operate through similarity: sign vehicles resemble or imitate the referents to which they are linked. They include direct physical similarity, such as a life-like portrait depicting a person, but also encompass more abstract resemblance, such as metaphors and diagrams.[31] Icons are also used in animal communication. For instance, ants of the species Pogonomyrmex badius use a smell-based warning signal that resembles the type of danger with a correspondence between intensity and duration of signal and danger.[32]

Indices are signs that operate through a direct physical link. Typically, the referent is the cause of the sign vehicle. For example, smoke indicates the presence of fire because it is a physical effect produced by the fire itself. Similarly, disease symptoms are signs of the disease causing them and a thermometer's gauge reading indicates the temperature responsible. Other material links besides a direct cause-effect relation are also possible such as a directional signpost physically pointing the path to a nearby campsite.[33]

Symbols are signs that operate through convention-based associations. For them, the relation between sign vehicle and referent is arbitrary. It arises from social agreements, which an individual needs to learn in order to decode the meaning. Examples are the numeral "2", the colors on traffic lights, and national flags.[34]

The categories of icon, index, and symbol are not exclusive, and the same sign may belong to more than one. For example, some road warning signs combine iconic elements, like an image of falling rocks to indicate rockslide, with symbolic elements, such as a red triangle to signal danger.[35] Various other categories are discussed in the academic literature. Thomas Sebeok expands the icon-index-symbol classification by adding three more categories: signals are signs that typically trigger behavioral responses in the receiver; symptoms are automatic, non-arbitrary signs; names are extensional signs that identify one specific individual.[36] Other categorizations of signs are based on the channel of transmission, the intentions of the communicators, vagueness, ambiguity, reliability, complexity, and type of referent.[37]

Models

Models of signs seek to identify the essential components of signs. Many models have been proposed and most introduce a unique terminology for the different components although they often share substantial conceptual overlap. A common classification distinguishes between dyadic and triadic models.[38]

Dyadic models assert that signs have essentially two components, a sign vehicle and its meaning. An influential dyadic model was proposed by Saussure, who names the components signifier and signified. The signifier is a sensible image, whereas the signified is a concept or an idea associated with this form. For Saussure, the sign is a relation that connects signifier and signified, functioning as a bridge from a sensory form to a concept. He understands both signifier and signified as psychological elements that exist in the mind. As a result, the meaning of signs is limited to the realm of ideas and does not directly concern the external objects to which signs refer. Focusing on language as a general model of signs, Saussure argued that the relation between signifier and signified is arbitrary, meaning that any sensible image could in principle be paired with any concept. He held that individual signs need to be understood in the context of sign systems, which organize and regulate the arbitrary connections.[40]

Various interpreters of Saussure's model, such as Louis Hjelmslev[e] and Roman Jakobson, rejected the purely psychological interpretation of signs. For them, signifiers are material forms that can be seen or heard, not mental images of material forms. Similarly, critics have objected to the idea that the relation between signs and signifiers are always arbitrary, pointing to iconic and indexical signs as counterexamples.[42][f]

Triadic models assert that signs have three components. An influential triadic model proposed by Peirce argues that the third component is required to account for the individual that interprets signs, implying that there is no meaning without interpretation. According to Peirce, a sign is a relation between representamen, object, and interpretant. The representamen is a perceptible entity, the object is the referent for which the representamen stands, and the interpretant is the effect produced in the mind of the interpreter.[45]

Peirce distinguishes various aspects of these components. The immediate object is the object as the sign presents it—a mental representation. The dynamic object, by contrast, is the actual entity as it really is, which anchors the meaning of the sign. The immediate interpretant is the sign's potential meaning, whereas the dynamic interpretant is the sign's actual effect or the understanding it produces. The final interpretant is the ideal meaning that would be reached after an exhaustive inquiry.[46] Peirce emphasizes that semiosis or meaning-making is a continuously evolving process. Analyzing Peirce's model, Umberto Eco talks of an "unlimited semiosis" in which the interpretation of one sign leads to more signs, resulting in an endless chain of signification.[47]

Another triadic model, proposed by Charles Kay Ogden and I. A. Richards, distinguishes between symbol, thought, and referent. Known as the semiotic triangle, it asserts that the connection between symbol and referent is not direct but requires the mediation of thought to establish the link.[48]

Remove ads

Sign systems

Summarize

Perspective

A sign system is a complex of relations governing how signs are formed, combined, and interpreted, such as a specific language. Signs usually occur in the context of a sign system, and some semiotic theories assert that isolated signs have little meaning apart from their systemic relations to other signs.[49]

Sign elements and texts

Sign systems often rely on basic constituents or sign elements to compose signs. For example, alphabetic writing systems use letters as sign elements to construct words, while Morse code uses dots and dashes. Letters are essential for differentiating word meanings, like the contrast between the words cat, rat, and hat based on their initial letter. The basic sign elements usually do not have a meaning of their own unless combined in systematic ways.[50]

A text is a large sign composed of several smaller signs according to a specific code.[51] Unlike basic sign elements, the units composing a text are themselves meaningful. The meaning of a text, called its message, depends on its components. However, it is usually not a mere aggregate of their isolated meanings, but shaped by their interaction and organization. In addition to linguistic texts, such as a novel or a mathematical formula, there are also non-linguistic texts, such as a diagram, a poster, or a musical composition consisting of several movements.[52] The capacity to create and understand texts, known as textuality, is also present in some non-human animals. For example, honey bees perform a complex dance combining diverse features to communicate information about their environment to other bees.[53]

The meaning of a text can depend on and refer to other texts—a feature called intertextuality.[54] Semioticians distinguish several aspects of texts. Paratext encompasses elements that frame or surround a text, such as titles, headings, acknowledgments, footnotes, and illustrations. Architext refers to the general categories to which a text belongs, such as its genre, style, medium, and authorship. A metatext is a text that comments on another text. A hypotext is a text that serves as the basis of another text, such as a novel that has a sequel or is parodied in another work. In such cases, the derivative text that refers to the earlier work is the hypertext.[55][g]

Structural relations between signs

The signs in a sign system are connected through several structural relations, like the contrast between syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations. Syntagmatic relations govern how individual signs or sign elements can be combined to form larger expressions. For example, sentences are linear arrangements of words, and syntagmatic relations govern which words can be combined to produce grammatically correct sentences. Similarly, a dinner menu is a sequence of courses with syntagmatic relations governing their arrangement, like beginning with a starter, followed by a main course and a dessert. Some sign systems use non-linear arrangements, such as traffic signs combining the shape of a sign with the symbol it shows.[58]

Paradigmatic relations are links between signs that belong to the same structural category. They specify which elements can occupy a particular position and can substitute for each other without breaking the system's rules. For example, in the sentence "The man sleeps.", the word man stands in paradigmatic relations to words like woman, child, and person because substituting them also results in a correct sentence. For the dinner menu, the same holds for the different options for the dessert, such as cake, ice cream, and fruit salad. In the case of traffic signs, there are paradigmatic relations between the shape options, such as triangle and circle. The meaning of the chosen paradigmatic option is influenced by the absent options, which form a background of meaningful alternatives. In natural language, these alternatives are typically related to specific word classes. For instance, when a particular word position in a sentence calls for a verb then the paradigmatic options consist of verbs.[59]

Another form of semiotic analysis examines sign pairs consisting of opposites where two signs denote contrasting features and exclude each other, like the pairs good/bad, hot/cold, and new/old. Some contrasts involve a continuous scale with intermediate levels, like fast/slow, whereas others are polar oppositions without degrees in between, such as alive/dead.[61] Early structuralist philosophy is associated with the idea that meaning arises primarily from binary oppositions.[62] The semiotic square, proposed by Algirdas Greimas, offers a more fine-grained differentiation. It relates a sign, such as rich, to three contrasting terms: its contradictory (not rich), its contrary (poor), and the contradictory of its contrary (not poor).[63]

Another structural feature is asymmetric sign pairs where one item is unmarked and the other marked. The unmarked sign is the generic and neutral expression often taken for granted, whereas the marked sign is specialized and denotes additional features. The unmarked term is more commonly used and is typically privileged as the default or norm. Examples are the pairs dog/bitch, day/night, he/she, and right/left. This asymmetry is of particular interest to the semiotic study of culture as a guide to implicit background assumptions and power relations.[64] For example, patriarchal societies tend to use unmarked forms for masculine terms, while unmarked forms for feminine terms are more common in matriarchal societies.[65]

Tropes

Semioticians study associative mechanisms through which a sign acquires alternative meanings by interacting with other signs. This change in meaning can occur in cases where the literal meaning of a sign is inadequate or absurd, leading to a shift toward a figurative meaning. For example, the term snake literally refers to a limbless reptile but has a different meaning in the sentence "The professor is a snake."[66]

The mechanisms through which this shift in meaning happens are called tropes. Discussions of tropes sometimes focus on four master tropes[h] as the basis of most others: metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, and irony.[68] A metaphor is an analogy in which attributes from one entity are carried over to another, such as associating the snake-like attributes of being sneaky and cold-blooded with a professor.[69] A metonymy is a way of referring to one object by naming another closely related thing, like speaking of a king as the crown.[70] Similarly, a synecdoche is a way of referring to one object by naming one of its parts, like speaking of one's car as my wheels.[71] The trope of irony works through dissimilarity, literally expressing the opposite of what is meant, such as remarking "Great job!" after a horrible failure.[72]

Semiotic tropes are primarily discussed in relation to linguistic sign systems, where they are also known as figures of speech. However, their underlying mechanisms also affect non-linguistic sign systems.[73] For example, an advertisement for an airline may juxtapose the landing of a plane with the tranquil touchdown of a swan as a pictorial metaphor for grace and reliability.[74] Comics often rely on pictorial metonymies to express emotions, like a raised fist to stand for anger.[75] In photography, close-ups can function as synecdoches by presenting the whole through a part.[76] In film, one type of audiovisual irony presents a horrific visual scene accompanied by incongruously cheerful music.[77]

Codes

A code is a sign system used to communicate. It includes a set of signs, the meaning relations among them, and the rules for combining them to create and interpret messages.[78][i] Digital codes rely on clear and precise distinctions of how signs are formed and combined, as in written language. They contrast with analog codes, which use continuous variations to convey meaning, such as seamless gradations of color in painting.[80] Simple codes include only few basic elements and relations, as in the color code of traffic signals. Complex codes, like the English language, can encompass countless elements as well as syntactic and sociocultural norms involved in meaning-making. Conventional codes are human-made constructs, including aesthetic codes used in the creation of artworks, like music and painting. They contrast with natural codes,[j] like DNA, which functions as a biochemical information system encoding hereditary information through nucleotide sequences.[82]

Semioticians analyze codes along several dimensions, such as the domain and context they operate in, the sensory channel they rely on, and the function they perform. Some codes focus on the precise expression of knowledge, such as mathematical formulas, while others govern cultural and behavioral norms, including conventions of politeness and ceremonial practices.[83] A code can have domain-specific subcodes that refine its scope of meaning or regulate usage in particular settings. Codes and subcodes are not static frameworks but can evolve as new conventions or technologies emerge.[84]

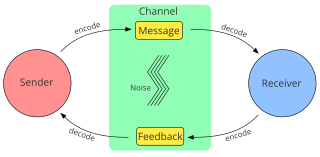

Code also plays a central role in models of communication—conceptual representations of the main components of communication. Many include the idea that a sender conveys a message through a channel to a receiver, who interprets it and may respond with feedback. Encoding is the process of expressing meaning in the form of a message using the system of a specific code. Decoding is the reverse process of interpreting the message to understand its meaning. In some cases, different codes can be used to express the same message. Similarly, messages can sometimes be translated from one code into another, such as transcribing a written text into Morse code.[86]

Discourse is the social use of language or other codes, taking place at a specific moment in a particular context. Discourse analysis examines how meaning arises in a discourse, considering the communicators and their respective roles, as well as the influences of context and institutional backgrounds.[87]

Semioticians are also interested in how codes reflect and shape human perception of the world.[88] By influencing perception, codes can affect behavior by making individuals aware of possible courses of action.[89] The controversial Whorfian hypothesis suggests that language shapes thought by providing fundamental categories of understanding, with the potential consequence that speakers of different languages think differently.[90]

Remove ads

Core branches

Summarize

Perspective

General semiotics studies the nature of signs and their operation within sign systems in the widest sense, independent of the domains to which they belong. It contrasts with applied semiotics, which examines signs in particular domains or from discipline-specific perspectives.[92] An influential categorization, proposed by Morris, divides general semiotics into three branches: syntactics, semantics, and pragmatics.[91]

Syntactics studies formal relations between signs. It investigates how signs combine to form compound signs and which rules govern this process. For example, the rules of grammar in natural languages specify how words may be arranged to form sentences and how different arrangements influence meaning. As a result of the syntactic rules of the English language, the expression "elephants are big" is grammatically correct, whereas "elephants big are" is not.[93] Syntactics is not limited to language and includes the study of non-linguistic compound signs, such as the arrangement of visual elements in geographic maps.[94]

Semantics studies the relation between signs and what they stand for, examining how signs refer to concrete things and abstract ideas. It typically focuses on the general meaning of a sign rather than its meaning in a particular context. Semantics addresses the meaning of both basic and compound signs. In the linguistic domain, it includes lexical semantics, which explores word meaning, and phrasal semantics, which studies sentence meaning.[95] Other areas include animal semantics, which investigates, for example, how animal warning calls stand for predators.[96]

Pragmatics studies the relation between signs and sign users. It examines how individuals produce and interpret signs in concrete contexts, applying syntactic insights into formal structures and semantic insights into general meaning to real-life situations. The pragmatic dimension of sign use in communication encompasses aspects such as social conventions and expectations, speaker intention, audience, and other contextual factors. For example, it depends on the concrete situation whether the expression "she found a mole" refers to the discovery of an animal, a skin mark, or a spy.[97]

Various academic discussions address the relation between the three branches, such as their relative importance or hierarchy. Historically, syntactics and semantics have received more attention than pragmatics, particularly in the study of linguistic sign systems. One reason for this preferential treatment is the idea that sign usage is largely determined by what signs mean and how they can be combined. As a result, pragmatics has often been regarded as a secondary discipline, reserved for diverse problems that could not be adequately addressed from the perspectives of the other two disciplines. However, this marginal treatment of pragmatics is questioned in the contemporary discourse. Some proposals reverse the priority and see pragmatics as the primary discipline. One reason is the idea that syntactics and semantics are abstractions that cannot be scientifically studied on their own without examining actual sign use.[98]

Remove ads

Applications

Summarize

Perspective

Biology

While traditional semiotics focuses on human communication and culture, biosemiotics integrates this perspective with biology. It studies how living beings produce and interpret signs through channels such as vision, sound, movement, and chemical cues like smell.[100] It does not restrict sign processes to conscious mental activities and explicitly includes nonintentional processes within its scope.[101] Biosemiotics has branches dedicated to different types of organisms, such as zoosemiotics (animals), phytosemiotics (plants), bacteriosemiotics (bacteria), mycosemiotics (fungi), and protistosemiotics (protists).[102] Anthroposemiotics, which addresses humans, is sometimes included in zoosemiotics or treated as a distinct branch.[103]

The scope of biosemiotics covers semiotic activities on different levels of organization, ranging from cellular information processes to communication between distinct individuals. At the microlevel, there are sign activities within individual organisms. For example, genes encode information about hereditary traits, and diverse biological processes decode and activate this information. Similarly, hormones function as signaling molecules that control physiological functions by conveying information over long distances in the body. Biosemioticians also study how nerve cells communicate with each other and how neurotransmitters regulate this process.[104] This topic is more closely examined by neurosemiotics, which investigates neural processes involved in sign interpretation and meaning-making.[105]

At the macrolevel, there are sign processes between distinct organisms. They happen primarily between individuals of the same species as forms of cooperation or coordination.[106] For example, birds use calls to attract mates, warn of predators, and maintain territorial boundaries.[99] Similar semiotic processes also happen in the plant kingdom, such as airborne chemicals released by maple trees as a warning signal of herbivore attacks.[107] In some cases, communication happens between members of distinct species.[108] For instance, flowers use symmetrical shapes and vivid colors as signs to guide insects to nectar.[109] Because of the pervasive nature of sign processes, biosemioticians typically argue that semiosis is not a rare phenomenon limited to specific biological niches but an intrinsic feature of life in general.[110]

Culture

Several branches of applied semiotics study cultural phenomena, which encompass systems of beliefs, values, norms, and practices shared in society. The semiotics of culture analyzes sign systems used in cultural practices by examining the meanings and ideological assumptions they embody. It integrates findings from fields such as psychology, anthropology, archaeology, linguistics, and neuroscience. It addresses both the fundamental characteristics of culture in general and the distinctive features of specific cultural formations, such as myths, aesthetics, cuisine, clothing, rituals, and artifacts.[111] On a more general level, the semiotics of culture explores how culture differs from nature and which processes are responsible for the emergence of cultural formations.[112] Social semiotics, a related field, studies sign practices as social phenomena in cultural contexts.[113] It also investigates the social construction of reality. This includes semiotic practices that establish social meanings, categories, and norms shaping how people perceive the world and what they take for granted.[114] Related fields include semiotic anthropology, which analyzes how sign systems reproduce, transmit, and change culture,[115] and ethnosemiotics, which examines and compares semiotic phenomena in specific ethnic groups.[116]

Semioticians have been particularly interested in cultural myths, which they understand as structures of meaning that codify ideologies. In this sense, myths are not only a specific genre of literature but encompass widely shared views about human nature or the world. For example, pervasive ideological myths in Western culture include the idea of progress, which frames history as a linear series of improvements, and individualism, which conceives individuals as autonomous and self-reliant agents. Myths help people make sense of experience and guide behavior through common frameworks that conceptualize phenomena. Semiotic analysis sees myths as secondary sign systems that use other signs as vehicles to convey their ideas, often in the form of metaphors. For instance, the image of a child represents a child on the literal level. However, it can at the same time embody a myth of childhood associated with innocence and purity, motivating social arrangements associated with protection and parenting. Semioticians analyze this secondary level of signification across diverse media, such as literature, film, and advertising.[117]

In specific areas of culture, semiotics examines the codes and conventions they employ and the meanings they produce.[118] The semiotics of clothing studies clothing as a nonverbal sign system. Clothes are often implicitly interpreted as signs of the personality and social status of the wearer, covering features such as gender, age, and political beliefs. Different social occasions are associated with distinct dress codes, such as uniforms for sport, the military, and religious rituals.[119] Similarly, the semiotics of food analyzes food items as bearers of cultural meanings. It explores how culinary practices reflect social organization and belief systems, like cooking methods, table etiquette, taboos against eating certain items, the cultural roles of fasting and feasting, and food symbolism.[120] Research topics in popular internet culture include the codes and conventions of emojis and internet memes.[121]

Literature

Text semiotics studies the meanings of linguistic texts. It typically focuses on larger fragments of discourse, leaving the analysis of smaller units, like phonemes, to linguistics.[122] Text semiotics plays a central role in literary criticism by exploring the codes, conventions, and tropes employed in literary texts. It situates these insights within broader cultural and semiotic frameworks.[123]

Central schools of thought in text semiotics include structuralism and poststructuralism.[124] Structuralism assumes that structural relations within sign systems are the primary source of meaning and understanding. It examines how texts employ these patterns, such as binary oppositions between good and evil or nature and culture, often with the goal of identifying ideological biases.[125] Post-structuralism argues that sign systems are self-referential and cannot provide a stable representation of reality. The post-structuralist method of deconstruction aims to reveal contradictions and ambiguities within texts, for example, by showing how a text unintentionally undermines a binary opposition on which it relies.[126]

A historically influential tradition in text semiotics is hermeneutics—the study of interpretation. Hermeneutics originates in the examination of mythological and religious texts. It was used by medieval Christian philosophers to decode the theological and moral doctrines of the Bible, for instance, by distinguishing literal from spiritual meanings and analyzing symbolic structures associated with allegories. Modern hermeneutics extends these practices to secular texts. The hermeneutic circle is a central concept in this field. It is the idea that understanding involves a circular movement in which preconceptions guide interpretation and interpretation shapes preconceptions. It is sometimes explained as an interplay where understanding the text as a whole depends on understanding its parts and vice versa.[127] It is debated whether there is a single correct interpretation of every text or whether incompatible interpretations can be valid at the same time.[128]

Narratology is a branch of semiotics that studies narrative texts, such as tales and stories. It assumes that there is a universal narrative code of the different elements found in narratives, meaning that individual texts only express variations of the same underlying code. For example, according to Algirdas Julien Greimas's actantial model, these elements include a subject, such as the hero of the story, an entity that they desire, and an opponent or obstacle to their goal.[129] Other research directions in text semiotics are stylistics and rhetorics, which compare different styles and explore how texts persuade.[130]

Arts and media

Semiotics has diverse applications in the analysis of art and other media, ranging from film and music to advertising and video games.[132] The field of media semiotics studies how meaning is produced, interpreted, and shared in media, such as newspapers, radio, television, and the internet. Understood in the widest sense, it encompasses all channels of everyday communication, including shop signs and posters.[133]

In the visual arts, semioticians examine how meaning is created through aspects such as color, shape, texture, composition, and perspective. For example, colors can express different moods, emotions, and atmospheres, such as warm and soft colors in contrast to cold and harsh ones. Colors can also have culture-specific symbolic meanings, such as pink signifying femininity.[134] Semioticians are further interested in the representational dimension of images, studying how they may act as icons that represent their motive through similarity. In photography, images may additionally function as indexical signs because of the causal connection between the depicted object and the photograph.[135]

Musical semiotics studies music as a meaning-making process involving signifiers and signifieds.[136] There is substantial disagreement about the extent to which music is a semiotic activity. Some theoretical attempts treat sounds as individual signs and compositions as compound signs or messages, while others argue that sounds and compositions signify nothing beyond themselves.[137] Another research approach investigates the cultural significance of music, for example, how musical styles, like heavy metal, reggae, and classical music, are associated with different subcultures and lifestyles.[138]

Film semiotics analyzes films as sign activities, exploring how visual and auditory codes interact. Some theorists compare films to language, arguing that individual shots act as words and that montages, which combine several shots, correspond to sentences. A key difference to many other forms of language is that film involves asymmetrical communication since there is usually no direct way for spectators to respond to messages.[139] The semiotics of architecture, another field, examines how buildings communicate meaning, including their practical functions, historical heritage, and social significance.[140]

The semiotics of advertising studies how advertisements use and combine signs to influence consumers. Advertisements typically combine linguistic and non-linguistic codes. For instance, print ads typically use language for the brand name and verbal commentary, while visual elements convey non-verbal messages to the target audience. In many cases, the core message, related to the economic reality of selling a product, is not stated explicitly. Instead, an indirect message is used to make the product appealing.[131]

Computer games integrate elements from many other media and combine them with an interactive dimension. They include diverse sign elements, for example, to explain how to interact with the virtual world, set goals, provide feedback, and establish a narrative.[141]

Cognition

Cognitive semiotics is an interdisciplinary field that examines how mental processes contribute to meaning-making. It integrates insights of diverse disciplines, covering semiotics, cognitive science, linguistics, anthropology, psychology, and philosophy.[142] Cognitive semioticians study sign activity from complementary perspectives: the subjective first-person perspective, the intersubjective second-person perspective, and the objective third-person perspective. While acknowledging the validity of each perspective in its respective area, the field privileges first-person and second-person methods as offering more direct access to the mental dimension of meaning. For example, it relies on the phenomenological description to analyze how sign processes shape experience.[143] By examining how meaning operates in the mind, it contrasts with certain aspects of biosemiotics that address sign processes without mental activity, like in genetics.[144]

Cognitive semioticians typically understand mind and cognition in terms of practical engagement with the world rather than theoretical attempts to model or depict it. They argue that meaning includes representation as one way of engaging with the world, but is not limited to it. Their primary focus is on non-representational forms of meaning, such as habits, values, and other ways how individuals attune to their environment. From this perspective, sign structures are understood as processes that shape habits and dispositions to act in different circumstances, emphasizing that meaning is a dynamic process rather than a static product.[145] The theory of finite semiotics explains semiosis as an effect of the finite nature of the human mind that occurs as an individual passes from one cognitive state to another.[146]

Others

In the field of non-verbal communication, semioticians investigate the exchange of information without linguistic sign systems.[147] For example, body language includes signifying practices like raising a thumb and other gestures, as well as facial expressions like laughing and frowning.[148] Other types of non-verbal communication encompass touching behavior, like shaking hands or kissing, and the use of personal space, such as the distance between speakers to express their degree of familiarity.[149] Paralanguage encompasses non-verbal elements of linguistic messages. For instance, pitch and loudness in a conversation can express emotion or emphasis without stating them explicitly.[150]

Semiotics has various applications in psychoanalysis. Sigmund Freud proposed a theory of dream interpretation to understand and resolve psychological conflicts. He argued that dream elements act as symbols that stand for unconscious desires and fears. For example, dreams of losing a tooth can signify castration or fear of impotence.[151] Semiotics also plays a central role in the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan, who argued that the unconscious is structured like a language.[152]

In the field of computing, semiotics has been used to describe programming languages and analyze human–computer interaction. There are also attempts to develop formal theories of semiotics, allowing computational processes to perform semiotic analyses.[153] Cybersemiotics, another approach, combines biosemiotics with cybernetics to provide a unified framework of semiotic processes across biological, social, and technological domains.[154]

Edusemiotics is a research movement that conceptualizes semiotic activity as the foundation of educational theory. For instance, it understands teaching and learning as sign processes.[155] Semioethics is a critical approach that examines the ethical dimension of sign activities. It seeks to diagnose problems that arise in the context of global communication.[156] Medical semiotics studies how disease symptoms, such as pain, dizziness, and fever, indicate medical conditions.[157] Legal semiotics investigates sign activities in legal practice, including the interpretation of evidence, testimony, and legal texts.[158]

Remove ads

Methods

Summarize

Perspective

Semioticians use diverse methods to analyze and compare signs and sign systems. Different domains of signs and perspectives of inquiry typically call for distinct techniques depending on the forms of representation and modes of meaning-making under study. As a result, there is no universally adopted methodology but only an interdisciplinary, loosely connected set of approaches.[159] Within a given domain, semioticians typically seek to determine what meaning is produced, why it emerges the way it does, and how it is encoded.[160]

Structural analysis examines the structural framework of texts and sign systems, exploring the syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations underlying signification. The commutation test is an influential tool for structural analysis. It explores how the meanings of linguistic and non-linguistic texts are shaped by their components and what roles specific signs play in this process. It proceeds by changing certain elements of a text, either actually or as a thought experiment, and assesses whether or how this change affects the overall meaning. For example, in the analysis of an advertisement, a semiotician may probe whether the overall message changes if a woman is shown using the product instead of a man. If it does then gender is a signifying element. The way how the overall message changes provides insights into the semiotic role of the changed aspect. The commutation test can be applied to a wide range of elements or features, such as shape, size, color, camera angle, typeface, age, class, and ethnicity. Instead of replacing one element with another, other versions of the commutation test add or remove elements to explore, for instance, what draws attention by its absence or what is taken for granted.[161][k]

In the study of cultural sign systems, semioticians often focus on hidden meanings and connotations, such as ideological messages and power dynamics that influence meaning-making without being immediately apparent to observers.[163] This dimension can be studied in diverse ways, such as comparing marked and unmarked terms to reveal how cultural norms privilege certain meanings and marginalize others.[64] Critical discourse analysis has a similar goal, seeking to understand how texts and social reality shape each other. It is particularly interested in how ideologies and power relations are reproduced in discourse, for example, by analyzing how political actors depict immigrants as threats to promote restrictive immigration policies.[164]

Another approach to semiotics focuses on the historical dimension of sign systems and semiotic practices. It examines how they came into existence and evolved, studying how the relevant codes and media developed and how new conventions and genres emerged. The historical inquiry also considers the effects of technological developments, for instance, by tracing how the invention of the printing press and the internet have shaped the way people engage with written texts.[165]

Although qualitative investigation is the dominant approach in semiotics, some researchers also use quantitative methods. For example, many forms of content analysis examine objective patterns found in an individual document or an entire discourse and employ statistical analysis to discover systematic patterns in sign usage. Applied to the news coverage of a violent incident, a content analyst may gather statistical information about how often the perpetrators are described as rebels rather than terrorists. Quantitative data on its own is usually not sufficient to explain complex semiotic processes, which is why content analysis is typically combined with other approaches.[166]

In applied semiotics, researchers often tailor their approach to the specific area of signs under investigation.[167] For instance, biosemioticians may adapt concepts intended for linguistic analysis to biological codes like DNA. In some cases, this requires conceptual modifications, for example, when terms like interpretation are applied to sign processes without a conscious subject.[168]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The study of signs has its origin in antiquity. Early approaches examined concrete patterns that indicate underlying conditions or future outcomes, such as medical diagnosis and divination. Some Mesopotamian tablets from the 3rd millennium BCE document this practice, such as the interpretation of the moon's visibility as a sign of an impending drought.[170] In ancient Greek thought, Hippocrates (460–377 BCE) and later Galen of Pergamum (c. 129–216 CE) investigated medical signs as indications of underlying diseases, establishing "semeiosis" or symptomatology as a branch of medicine.[169] In philosophy, Plato (427–347 BCE) explored whether the relation between linguistic signs and their referents is natural or conventional.[171] His student Aristotle (384–322 BCE) distinguished verbal from nonverbal signs. He argued that verbal signs represent mental states, which refer to external things, while nonverbal signs guide inference to expand knowledge.[172][l] Starting in the 3rd century BCE, the Stoics defended a triadic model of signs, understanding sign vehicle and referent as material objects linked through nonmaterial meaning. In the same period, the Epicureans proposed a dyadic model, emphasizing a direct connection between sign vehicle and referent without meaning as a separate component to link them.[174] Philodemus (c. 110–40 BCE) provided a detailed overview of discussions about the Epicurean theory of signs, such as whether signs function as inferences from the known to the unknown.[175]

In ancient India, various schools of Hinduism examined semiotic phenomena. Nyaya studied the relations between names, things, and knowledge, while Mīmāṃsā addressed the connection between word meaning and sentence meaning.[177] The philosopher Bhartṛhari (4th–5th century CE) developed and compared theories of meaning, arguing that sentences are the primary bearers of meaning. He asserted that cognition depends on linguistic categorization, for example, that names make it possible to individuate and perceive distinct objects.[178] Semiotic thought is also present in Buddhist philosophy. The Mahayana-sutra-alamkara-karika, a text from the 4th century CE, explored the spiritual role of semiosis, suggesting that the soteriological goal is to transform cognition in such a way that semiotic activity ceases.[179] In ancient China, Mohism understood sign use as the practical skill of drawing distinctions and argued that public, intersubjective standards ground meaning. The School of Names explored the relation between names and things. They practiced a method of public disputation, for example, to decide whether two names refer to the same thing or to different things.[180]

As a forerunner of semiotics in the medieval period, Augustine (354–430) drew on Stoic, Epicurean, and Christian ideas to develop one of the first systematic theories of signs. He examined the relations between signs, meanings, and interpreters. Augustine's theory included non-linguistic signs based on the distinction between natural and conventional signs.[182] Boethius (480–528) analyzed sign activity as a chain of signification: writing refers to speech, speech expresses mental concepts, and mental concepts represent external things.[183] Peter Abelard (1079–1142) studied non-linguistic sign processes, such as images and conventional gestures.[184] The most detailed medieval account of signs was proposed by Roger Bacon (c. 1214–1293), who understood signs as triadic relations between sign vehicle, represented thing, and interpreter. He developed a complex classification that distinguishes between natural signs and signs directed by the soul, with several subtypes in each category.[185] The Modist grammarians proposed that all languages share a universal grammar that reflects the shared structure of modes of being, understanding, and signifying.[181] William of Sherwood (c. 1200–1272), Peter of Spain (c. 1210–1277), and William of Ockham (c. 1285–1349) formulated contextual theories of meaning and reference.[186] In the Islamic world, philosophers explored semiotic topics from a religious perspective. They addressed the problem of how to interpret signs of Allah in the Quran and whether to describe Allah by affirming or negating attributes. Influential theorists were al-Kindi, al-Farabi, and Avicenna.[187]

In the early modern period, John Poinsot (1589–1644) integrated ideas of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) to investigate how signs mediate between objective reality and subjective experience.[188] The Port-Royal school, another tradition, formulated a mind-based theory of signs. It argued that signs consist of two ideas: one for the representing entity and one for the represented entity.[189] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) understood signs as visible marks that stand for ideas. He saw them as indispensable tools of thought, enabling operations on complex semantic concepts without apprehending them in full.[190] John Locke (1632–1704) proposed a general science or doctrine of signs to examine the link between knowledge and representation. He distinguished two types of signs: ideas are signs of things, and words are signs of ideas, effectively functioning as signs of signs.[191] Christian Wolff (1679–1754) and Johann Heinrich Lambert (1728–1777) both developed theories of signs while focusing on how knowledge depends on sign activity.[192]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, semiotics emerged as a distinct field of inquiry. The twin origins of this process lie in the works of the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) and the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913), who separately articulated the foundational principles of the discipline.[193] Peirce developed a triadic model, understanding signs as relations that can apply to any sign vehicle that is interpreted to stand for something else. He distinguished different types of relations between sign vehicle and referent and used this distinction to classify signs as indices, icons, and symbols. As a pragmatist, Peirce focused on the effects of sign processes while emphasizing the dynamic nature of meaning.[194] Charles W. Morris (1901–1979) popularized Peircean semiotics and integrated it with behaviorism. He conceptualized syntactics, semantics, and pragmatics as the main branches of the field.[195]

Saussure proposed a dyadic model that understands signs as relations in the mind between a sensible form and a concept. He emphasized the arbitrary nature of this relation and explored how signs form sign systems, such as language. Saussure distinguished synchronic or static from diachronic or historical aspects of language.[m] He formulated the foundations of structuralism to investigate how differences between signs, such as binary oppositions, are the primary mechanism of meaning.[196] Based on Saussure's structuralism, Louis Hjelmslev (1899–1965) developed glossematics, which divides language into basic units defined only by the formal functions they play in a sign system.[197] Focused on articulating a general semiotics, Algirdas Julien Greimas (1917–1992) expanded glossematics and applied it to narratology, aiming to discern a universal code underlying narrative texts.[198] Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) employed the principles of structural semiotics to engage in ethnology, analyzing myths and cultural practices as sign systems that reveal how different cultures make sense of the world.[199] Roland Barthes (1915–1980) used the theories of Saussure and Hjelmslev to study literature and media, covering signifying processes in myths, theology, pictures, advertising, and fashion. In these fields, he often examined how connotations encode subtle ideological messages.[200]

Using the phenomenological method, Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) studied the nature of signs and meaning through the description of experience. He contrasted the direct awareness of objects in perception with the indirect awareness of objects that refer to something other than themselves.[202] In psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) interpreted dream elements as signs of unconscious desires. Jacques Lacan (1901–1981) expanded Freud's ideas, analyzing the structure of the unconscious as a sign system.[203] Drawing on psychoanalysis and feminism, Julia Kristeva (1941–present) has explored the problem of intertextuality and conceptualized the semiotic and the symbolic as two contrasting dimensions of signification.[201]

Jakob von Uexküll (1864–1944) pioneered the study of animal and plant semiosis. He understood the interaction between organism and environment as a process of sign exchange in which individuals respond to cues that are relevant to their species-specific needs and capacities. Uexküll argued that different species inhabit distinct perceptual worlds based on their selective interpretation of cues.[204] Thomas A. Sebeok (1920–2001) relied on Uexküll's ideas to establish biosemiotics as a branch of semiotics, covering sign processes within and between organisms, such as animals, plants, and fungi.[205]

Roman Jakobson (1896–1982) contributed to various schools of thought, including Russian formalism, the Prague School, and the Copenhagen School. Adopting structuralism, he reinterpreted Saussure's dyadic model and later incorporated Peircean ideas, such as an emphasis on contextual factors.[206][n] Yuri Lotman (1922–1993) engaged in cultural semiotics, analyzing cultural formations in terms of models that showcase distinctive features of their origin culture.[208] Umberto Eco (1932–2016) understood semiotics as the study of communicative processes in culture, focusing the field on conventional codes. He explored the idea of unlimited semiosis, according to which the interpretation of signs is an open-ended process leading to further signs.[209] Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) was an influential proponent of poststructuralism. He developed the method of deconstruction to discover internal ambiguities and contradictions within texts.[210] The second half of the 20th century saw the emergence of many journals dedicated to semiotics, while international institutions, such as the International Association for Semiotic Studies, were established.[211]

Remove ads

See also

- Ecosemiotics – Branch of semiotics

- Index of semiotics articles

- Outline of semiotics – Overview of and topical guide to semiotics

- Philosophy of language

- Semiofest – Conference series and event on semiotics

- Semiotica – Academic journal on semiotics

- Sign Systems Studies – Academic journal on semiotics

- The American Journal of Semiotics – Academic journal on semiotics

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads