Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Senate of the Philippines

Upper house of the Congress of the Philippines From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

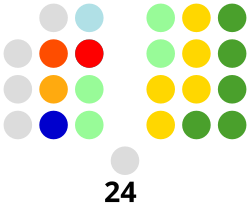

The Senate of the Philippines (Filipino: Senado ng Pilipinas) is the upper house of Congress, the bicameral legislature of the Philippines, with the House of Representatives as the lower house. The Senate is composed of 24 senators who are elected at-large (the country forms one district in senatorial elections) under a plurality-at-large voting system.

Senators serve six-year terms with a maximum of two consecutive terms, with half of the senators elected in staggered elections every three years. When the Senate was restored by the 1987 Constitution, the 24 senators who were elected in 1987 served until 1992. In 1992, the 12 candidates for the Senate obtaining the highest number of votes served until 1998, while the next 12 served until 1995. This is in accordance with the transitory provisions of the Constitution. Thereafter, each senator elected serves the full six years. From 1945 to 1972, the Senate was a continuing body, with only eight seats up every two years.

Aside from having its concurrence on every bill in order to be passed for the president's signature to become a law, the Senate is the only body that can concur with treaties and try impeachment cases. The president of the Senate is the presiding officer and highest-ranking official of the Senate. They are elected by the entire body to be their leader and are second in the Philippine presidential line of succession. The current officeholder is Francis Escudero.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The Senate has its roots in the Philippine Commission of the Insular Government. Under the Philippine Organic Act, from 1907 to 1916, the Philippine Commission headed by the governor-general of the Philippines served as the upper chamber of the Philippine Legislature, with the Philippine Assembly as the elected lower house. At the same time the governor-general also exercised executive powers.

In August 1916 the United States Congress enacted the Philippine Autonomy Act or popularly known as the "Jones Law", which created an elected bicameral Philippine Legislature with the Senate as the upper chamber and with the House of Representatives of the Philippines, previously called the Philippine Assembly, as the lower chamber. The governor-general continued to be the head of the executive branch of the Insular Government. Senators then were elected via senatorial districts via plurality-at-large voting; each district grouped several provinces and each elected two senators except for "non-Christian" provinces where the governor-general of the Philippines appointed the senators for the district.

Future president Manuel L. Quezon, who was then Philippine Resident Commissioner, encouraged future president Sergio Osmeña, then Speaker of the House, to run for the leadership of the Senate, but Osmeña preferred to continue leading the lower house. Quezon then ran for the Senate and became Senate President serving for 19 years (1916–1935).

This setup continued until 1935, when the Philippine Independence Act or the "Tydings–McDuffie Act" was passed by the U.S. Congress which granted the Filipinos the right to frame their own constitution in preparation for their independence, wherein they established a unicameral National Assembly of the Philippines, effectively abolishing the Senate. Not long after the adoption of the 1935 Constitution several amendments began to be proposed. By 1938, the National Assembly began consideration of these proposals, which included restoring the Senate as the upper chamber of Congress. The amendment of the 1935 Constitution to have a bicameral legislature was approved in 1940 and the first biennial elections for the restored upper house was held in November 1941. Instead of the old senatorial districts, senators were elected via the entire country serving as an at-large district, although still under plurality-at-large voting, with voters voting up to eight candidates, and the eight candidates with the highest number of votes being elected. While the Senate from 1916 to 1935 had exclusive confirmation rights over executive appointments, as part of the compromises that restored the Senate in 1941, the power of confirming executive appointments has been exercised by a joint Commission on Appointments composed of members of both houses. However, the Senate since its restoration and the independence of the Philippines in 1946 has the power to ratify treaties.

The Senate finally convened in 1945 and served as the upper chamber of Congress from thereon until the declaration of martial law by President Ferdinand Marcos in 1972, which shut down Congress. The Senate was resurrected in 1987 upon the ratification of the 1987 Constitution. However, instead of eight senators being replaced after every election, it was changed to twelve.

Remove ads

Composition

Article VI, Section 2 of the 1987 Philippine Constitution provides that the Senate shall be composed of 24 senators who shall be elected at-large by the qualified voters of the Philippines, as may be provided by law.

The composition of the Senate is smaller in number as compared to the House of Representatives. The members of this chamber are elected at large by the entire electorate. The rationale for this rule intends to make the Senate a training ground for national leaders and possibly a springboard for the presidency.[1]

It follows also that the senator will have a broader outlook of the problems of the country, instead of being restricted by narrow viewpoints and interests by having a national rather than only a district constituency.[1]

The Senate Electoral Tribunal (SET) composed of three Supreme Court justices and six senators determines election protests on already-seated senators. There had been three instances where the SET has replaced senators due to election protests, the last of which was in 2011 when the tribunal awarded the protest of Koko Pimentel against Migz Zubiri.[2]

Remove ads

Qualifications

The qualifications for membership in the Senate are expressly stated in Section 3, Article VI of the 1987 Philippine Constitution, as follows:

No person shall be a Senator unless he is a

- natural-born citizen of the Philippines, and on the day of the election, is

- at least 35 years of age,

- able to read and write,

- a registered voter, and

- a resident of the Philippines for not less than two years immediately preceding the day of the election.

The age is fixed at 35 and must be possessed on the day of the election, that is, when the polls are opened and the votes cast, and not on the day of the proclamation of the winners by the board of canvassers.

With regard to the residence requirements, it was ruled in the case of Lim v. Pelaez that it must be the place where one habitually resides and to which he, after absence, has the intention of returning.

The enumeration laid down by the 1987 Philippine Constitution is exclusive under the Latin principle of expressio unius est exclusio alterius. This means that Congress cannot anymore add additional qualifications other than those provided by the 1987 Philippine Constitution.

Organization

Summarize

Perspective

Under the Constitution, "Congress shall convene once every year on the fourth Monday of July for its regular session...". During this time, the Senate is organized to elect its officers. Specifically, the 1987 Philippine Constitution provides a definite statement to it:

(1) The Senate shall elect its President and the House of Representatives its Speaker by a vote of all its respective members.

(2) Each House shall choose such other officers as it may deem necessary.

(3) Each House may determine the rules of its proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly behavior, and, with the concurrence of two-thirds of all its Members, suspend or expel a Member. A penalty of suspension, when imposed, shall not exceed sixty days.

— Article VI, Section 16, paragraphs 1 to 3, The Constitution of the Philippines

By virtue of these provisions of the Constitution, the Senate adopts its own rules, otherwise known as the "Rules of the Senate." The Rules of the Senate provide the following officers: a president, a president pro tempore, a secretary and a sergeant-at-arms.

Following this set of officers, the Senate as an institution can then be grouped into the Senate Proper and the Secretariat. The former belongs exclusively to the members of the Senate as well as its committees, while the latter renders support services to the members of the Senate.

The secretary and sergeant-at-arms are elected by the senators from among the employees and staff of the Senate. Meanwhile, the Senate president, the Senate president pro tempore, the majority floor leader, and the minority floor leader are elected from among the senators themselves.

Within the Senate, senators organize themselves into two main coalitions or blocs: the majority bloc and the minority bloc. These blocs are roughly analogous to the ruling coalition and the opposition in other legislatures. The majority and minority groupings help streamline legislative business by aligning members into those who support the chamber's leadership and those who constitute the opposition. Each bloc selects its own leaders to speak and act on its behalf during Senate sessions. This majority–minority structure is central to how the Philippine Senate operates, shaping everything from leadership positions to committee control and the flow of legislation.[3]

At the start of each new Congress (every three years when the Senate convenes after an election), senators decide whether to join the majority or minority. By longstanding practice, those who vote for the winning candidate for Senate President—the chamber's presiding officer—form the majority bloc, while those who vote for a different candidate (or otherwise choose not to align with the winner) form the minority bloc.[4] This tradition means bloc affiliation is not strictly based on political party, but rather on alliances and choices in the Senate's internal leadership elections. For example, in the 19th Congress (2022), almost all senators voted for a single Senate President candidate, resulting in a supermajority coalition of about 20 senators, while only two senators opted to form the minority bloc.[5] In previous Congresses, minority blocs have typically ranged from around 4 up to 9 members out of the 24-seat Senate, depending on political alignments of the day.[6] The rest of the Senate (usually the larger share) joins the majority. It is unusual for a senator to remain outside both blocs—those who attempt to be "independent" of either side often end up with no committee positions or influence until they align with one of the blocs.[5]

Because Philippine senators come from diverse parties (the Senate uses a multi-party system with senators elected at-large), both the majority and minority blocs are usually coalitions of multiple parties and independents rather than single-party caucuses. Senators often shift alliances after elections—for instance, many will join the majority coalition supporting the Senate leadership (often aligned with the incumbent president's agenda), even if they campaigned under different parties. The minority bloc, on the other hand, is generally composed of those in opposition to the current administration or Senate leadership. In practice, this means the majority bloc can include a broad spectrum of parties united by convenience or common support for the leadership, while the minority bloc is a smaller cross-party group representing the legislative opposition.

Membership in the Commission on Appointments is proportional to the size of blocs. This means the Senate's majority bloc receives a larger share of seats in that commission, while the minority bloc gets a smaller representation.

Majority bloc

The majority bloc controls the Philippine Senate's leadership positions. Its members, being the larger group, elect the Senate President, who is the head of the chamber and typically a senior figure from the majority. The Senate President presides over sessions and is considered the most powerful individual in the Senate. The majority bloc also chooses the Senate Majority Leader (also called Majority Floor Leader) from among its ranks.[3] The Majority Leader serves as the floor leader for the majority coalition and the Senate's primary legislative manager. In the Senate, the Majority Leader's primary responsibility is to manage the chamber's legislative business—scheduling debates and steering the majority's bills through the Senate.[1] By tradition, the Majority Leader is concurrently the chairperson of the Senate Committee on Rules, giving them significant influence over the calendar of bills and the rules of debate. This makes the Majority Leader the Senate's agenda-setter, coordinating closely with the Senate President to decide which bills are prioritized for debate and voting.[3]

Because the majority bloc has the numerical strength, it holds sway over decisions in the Senate. The majority elects other officers (such as the Senate President Pro Tempore and committee chairpersons) and generally has the votes to pass legislation it favors. In Philippine legislative practice, the majority bloc works to advance the administration or majority coalition's legislative program, using its superior numbers to approve bills, budgets, and confirmations. Senators in the majority often receive chairmanships or memberships in key committees, reflecting their bloc's dominance. The majority bloc, holding the Senate's top offices, also controls many internal resources—for instance, office budgets for committee work, staff support for committees, and the flow of official Senate communications. In essence, the majority bloc "controls" the Senate: it occupies the top posts and most committee leadership roles, it can prioritize bills for passage, and it controls many of the chamber's internal resources. However, the majority is expected to govern responsibly, as it faces oversight and debate from the minority.[5]

Minority bloc

The minority bloc is the officially recognized opposition group in the Senate. Its members did not support the prevailing Senate President and thus organized themselves as a check on the majority. The Senate Minority Leader (also known as the Minority Floor Leader) is often informally called the Senate's "shadow president", in the sense that they lead the opposition and can serve as an alternative voice to the Senate President's leadership.[1] The Minority Leader's role is to be the chief spokesperson and strategist for the minority. They articulate the minority bloc's positions and are expected to constructively criticize the policies and programs advanced by the majority.[7] In Philippine legislative parlance, this duty of the minority to scrutinize and offer alternatives is sometimes referred to as "fiscalizing"—acting as fiscal watchdogs and critics of the government's proposals.[8]

Even though they lack the votes to win on their own, the Minority Leader and the minority bloc provide checks and balances by debating bills, pointing out flaws or issues, and proposing amendments. The Minority Leader is typically given the floor to respond to major speeches by the majority and to represent the dissenting view. By tradition, the Senate Minority Leader does not hold any committee chairmanships, in order to focus on leading the opposition (and perhaps to avoid conflicts of interest in overseeing executive programs).[5] Instead, the Minority Leader is usually granted membership in all committees as an ex officio member, ensuring the minority is represented in every committee's discussions.[9] Minority bloc members can sit in committees (and even head a few select committees on occasion if the majority permits), but in general the minority has fewer committee leadership positions. Minority senators use the committee platform to ask probing questions and air the opposition's concerns on legislation and public issues.[10]

Even with limited numbers, a minority bloc can influence public opinion and sometimes sway legislation by building coalitions issue-by-issue. Political observers and scientists warn that if the minority bloc becomes too small or ineffective, the Senate could turn into a mere "rubber stamp" for the executive branch's agenda, undermining the principle of separation of powers.[11]

Remove ads

Legislative powers

Summarize

Perspective

The Philippine Senate was modeled upon the United States Senate; the two chambers of Congress have roughly equal powers, and every bill or resolution that has to go through both houses needs the consent of both chambers before being passed for the President of the Philippines's signature. Once a bill is defeated in the Senate, it is lost. Once a bill is approved by the Senate on third reading, the bill is passed to the House of Representatives, unless an identical bill has also been passed by the lower house. When a counterpart bill in the lower house is different from the one passed by the Senate, either a bicameral conference committee is created consisting of members from both chambers of Congress to reconcile the differences,[12] or either chamber may instead approve the other chamber's version to expedite passage.[13] Aside from a few special cases of origination (discussed below), the Senate's legislative power is essentially equal to that of the lower house,[14] unlike in some parliamentary systems where an upper chamber may have limited veto power.[15]

Financial and appropriation measures

One constitutional exception in the legislative process is that certain types of bills must originate in the House of Representatives. The 1987 Constitution provides that all "appropriation, revenue or tariff bills, bills authorizing an increase of the public debt, bills of local application, and private bills" (which include franchise bills for public utilities or corporations) shall start in the House. However, the Senate retains the right to "propose or concur with amendments" to these House-initiated measures.[16] This means budget laws, tax measures, and franchise bills are first filed and approved in the House, but the Senate can fully scrutinize, modify, or even reject such bills when they reach its chamber. No money bill takes effect without the Senate's consent, ensuring a balance where neither chamber can legislate unilaterally on national laws.

Public oversight

Beyond lawmaking, the Senate helps oversee the executive branch and public agencies. Under Article VI, Section 21 of the Constitution, the Senate (or any of its committees) may conduct inquiries "in aid of legislation".[16] In practice, this oversight power allows the Senate to hold hearings and investigations on matters of public interest, government performance, and potential wrongdoing by officials. Such legislative inquiries are meant to gather information for crafting laws or to monitor and check the implementation of existing laws. The Senate can compel officials or private citizens to testify and produce documents as needed for these investigations. The Supreme Court has affirmed that the power to conduct inquiries carries implicit authority to enforce attendance and testimony—for example, the Senate may cite recalcitrant witnesses in contempt or order their arrest to ensure cooperation.[17] High-profile investigations (sometimes termed "blue ribbon" inquiries) are conducted by the Senate into allegations of corruption, misuse of funds, or other national issues. Through its oversight functions, the Senate helps ensure that laws are faithfully executed by the executive and that government officials remain accountable to the public.

Confirming executive appointments

The Senate also exerts influence over executive and judicial appointments via its participation in the Commission on Appointments (CA), a constitutional body that reviews and approves certain presidential appointments. It is composed of 25 members: the Senate President as ex officio chairperson, plus 12 senators and 12 members of the House of Representatives (selected by their respective chambers proportionally from blocs). Under the Constitution, appointments to key government positions require the Commission's consent before the officials can fully assume office. These positions include the heads of executive departments (Cabinet Secretaries), ambassadors and other high-ranking diplomats, officers of the armed forces above the rank of colonel, and heads or commissioners of independent constitutional bodies (such as the Commission on Elections, Civil Service Commission, and Commission on Audit), among others. In performing this function, the senators (who form one-half of the CA's membership) have substantial say in confirming or rejecting presidential nominees. The Senate President presides over the CA but votes only to break ties. This process ensures legislative oversight of high-level appointments—it prevents the Philippine president from installing officials in important posts without bipartisan consent. If the Commission on Appointments disapproves an appointment, or if it fails to act within 30 session days, the appointment is not confirmed and the nominee cannot continue in office. Through the CA, the Senate (together with the House contingent) performs a critical advise-and-consent function, similar to the confirmation powers of the U.S. Senate but exercised by a joint body in the Philippine system.[18]

Treaty concurrence

The Senate of the Philippines has the authority to concur in treaties. While the President holds the power to negotiate and sign treaties and international agreements, no treaty can take effect and bind the Philippines without the Senate's consent. The Constitution (Article VII, Section 21) states that "no treaty or international agreement shall be valid and effective unless concurred in by at least two-thirds of all the Members of the Senate".[16] Therefore, at least 16 affirmative votes are required to ratify a treaty. The House of Representatives is not involved in the treaty ratification process—this power resides solely in the Senate, a design inspired by the United States Senate's role in foreign treaties. For example, agreements on defense, trade, or diplomatic relations with other countries must be submitted to the Senate for its concurrence after presidential signing. If the Senate withholds its concurrence (or votes to reject a treaty), the treaty cannot become part of Philippine law or obligation. In contrast, purely executive agreements that do not rise to the level of a treaty may be entered by the President and are generally not subject to Senate approval.[19]

Impeachment trials

The Senate has an exclusive role in impeachment trials. Under the Constitution, the power to initiate an impeachment rests with the House of Representatives (which brings forward impeachment charges, called the articles of impeachment). However, once the House impeaches an official, the Senate alone has the authority to sit as the impeachment court to try the case and render judgment. Article XI, Section 3(6) of the Constitution vests in the Senate "the sole power to try and decide all cases of impeachment".[20][21] All senators act as judges in impeachment trials, with the Senate President presiding—except when the President of the Philippines is on trial, in which case the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court presides over the Senate impeachment court (although the Chief Justice does not vote). The Senate has broad authority to conduct a full trial—including summoning witnesses, receiving evidence, and ultimately deciding whether to convict the official from office. If convicted, the official is removed from office and may also be barred from holding any future public office. To convict an impeached official and remove them from office, a two-thirds vote of all senators (at least 16 out of 24 senators) is required. The Senate's judgment in impeachment is final as to removal, although the dismissed official may still face criminal or civil liability in the courts after removal. In exercising this power, the Senate serves as a check on the executive and judicial branches, since it can hold the President, Vice President, Supreme Court Justices, and other constitutional officers accountable for impeachable offenses (such as treason, bribery, graft and corruption, betrayal of public trust, or culpable violations of the Constitution).[21]

Other powers and functions

In addition to the major powers outlined above, the Senate shares in a number of other constitutional functions of Congress. For instance, only the Congress (Senate and House jointly) may declare the existence of a state of war, which requires a two-thirds vote in joint session voting separately. The Senate also participates in Congress's authority to approve or revoke the President's suspension of civil liberties or declaration of martial law in emergencies, by majority vote of all members voting jointly. Furthermore, an amnesty proclamation issued by the President requires concurrence of a majority of all members of Congress (Senators and Representatives voting together). These extraordinary powers, however, are exercised by the Senate collectively with the House, rather than by the Senate alone. The Senate's internal leadership—headed by the Senate President—also plays a role in the broader government (for example, the Senate President is third in the line of succession to the presidency and co-chairs the Joint Congressional Oversight Committees on certain laws).[16]

Remove ads

Current members

Leadership

Members

Per bloc and party

Remove ads

Seat

Summarize

Perspective

The Senate currently meets at the GSIS Building along Jose W. Diokno Boulevard in Pasay. Built on land reclaimed from Manila Bay, the Senate shares the complex with the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS).

The Senate previously met at the Old Legislative Building in Manila until May 1997. The Senate occupied the upper floors (the Session Hall now restored to its semi-former glory) while the House of Representatives occupied the lower floors (now occupied by the permanent exhibit of Juan Luna's Spoliarium as the museum's centerpiece), with the National Library at the basement. When the Legislative Building was ruined in World War II, the House of Representatives temporarily met at the Old Japanese Schoolhouse at Lepanto Street (modern-day S. H. Loyola Street),[23] while the Senate's temporary headquarters was at the half-ruined Manila City Hall.[24] Congress then returned to the Legislative Building in 1950 upon its reconstruction. When President Ferdinand Marcos dissolved Congress in 1972, he built a new legislative complex in Quezon City. The unicameral parliament known as the Batasang Pambansa eventually met there in 1978. With the restoration of the bicameral legislature in 1987, the House of Representatives inherited the complex at Quezon City, now called the Batasang Pambansa Complex, while the Senate returned to the Congress Building, until the GSIS Building was finished in 1997. Thus, the country's two houses of Congress meet at different places in Metro Manila.

The Senate would eventually move to the New Senate Building at the Navy Village in Fort Bonifacio, Taguig by 2025 at the earliest.[25] As the Senate has rented GSIS for the office space, it asked the Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA) to present suitable sites for it to move to, with the Senate eyeing the Navy Village property along Lawton Avenue as its favored site.[26] In 2018, a building designed by AECOM was chosen as winner for the new home for the Senate and was expected to be built by 2022. Civil works to erect the building had been awarded to Hilmarcs Construction Corporation, the same company the Senate investigated for alleged overpriced construction of the Makati City Hall Parking Building II in 2015.[27] The reception to the design was mixed, with some Filipino netizens comparing it to a garbage can.[28] By early 2021, the New Senate Building's construction was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines.[29]

Remove ads

Recent elections

Summarize

Perspective

These are the two recent elections that determined the current membership of the 20th Congress of the Philippines.

2025

- Guest candidate of DuterTen

2022

- Guest candidate of the UniTeam

- Guest candidate of the MP3 Alliance

- Guest candidate of Tuloy ang Pagbabago

- Guest candidate of the Lacson–Sotto slate

- Guest candidate of Team Robredo–Pangilinan

- Guest candidate of Aksyon Demokratiko

- Guest candidate of Laban ng Masa

Remove ads

Historical makeup

Summarize

Perspective

This is how the Senate looked like after the beginning of every Congress under the 1987 constitution. The parties are arranged alphabetically, with independents at the rightmost side. Vacancies are denoted by dashes after the independents. Senators may switch parties or become independents mid-term.

Prominent senators

Summarize

Perspective

Presidents of the Philippines

- Manuel L. Quezon – 2nd President of the Philippines and 1st Senate President; lobbied for a nationally-elected Senate, which was established in 1940

- Jose P. Laurel – 3rd President

- Sergio Osmeña – 4th President, 1st Speaker of the House of Representatives, and 1st Vice President of the Philippines

- Manuel Roxas – 5th President, 2nd Senate President, and 2nd Speaker of the House of Representatives; first Filipino to have served as chief of both the upper and lower house; recipient of the Quezon Service Cross

- Elpidio Quirino – 6th President and 2nd Vice President

- Carlos P. Garcia – 8th President and 4th Vice President

- Ferdinand Marcos – 10th President and 9th Senate President

- Joseph Estrada – 13th President and 9th Vice President

- Gloria Macapagal Arroyo – 14th President, 10th Vice President (first female Vice President), and 21st Speaker of the House of Representatives (first female House Speaker)

- Benigno Aquino III – 15th President

- Bongbong Marcos – 17th President

Vice Presidents of the Philippines

- Fernando Lopez – 3rd and 7th Vice President of the Philippines

- Emmanuel Pelaez – 6th Vice President

- Salvador Laurel – 8th Vice President

- Teofisto Guingona Jr. – 11th Vice President

- Noli de Castro – 12th Vice President

Speakers of the House of Representatives

- Quintín Paredes – 3rd Speaker of the House of Representatives and 5th Senate President

- Gil Montilla – 4th Speaker of the House of Representatives

- Benigno Aquino Sr. – former Speaker of the National Assembly (Second Philippine Republic)

- Jose Zulueta – 8th Speaker of the House of Representatives and 8th Senate President

- Manny Villar – 16th Speaker of the House of Representatives and 20th Senate President

- Alan Peter Cayetano – 22nd Speaker of the House of Representatives

Chief Justices of the Philippines

- José Yulo – 6th Chief Justice of the Philippines and former Speaker of the National Assembly of the Philippines

- Marcelo Fernan – 18th Chief Justice and 16th Senate President; the first and only Filipino to have served as chief of the Senate and the judiciary

Framers of the 1987 Philippine Constitution

- Domocao Alonto – lawyer, educator, author, traditional leader, and Islamic figure from Lanao del Sur

- Blas Ople – president of the 60th International Labour Conference of the International Labour Organization (ILO) and former Secretary of Foreign Affairs

- Ambrosio Padilla – vice president of the 1986 Philippine Constitutional Commission

- Soc Rodrigo – playwright, poet, journalist, broadcaster, lawyer, and Marcos-era opposition leader

- Decoroso Rosales – member of the 1986 Philippine Constitutional Commission

- Lorenzo Sumulong – former Senate President pro tempore of the Philippines

Recipients of the Quezon Service Cross

- Benigno Aquino Jr. – Marcos-era opposition leader, husband of the 11th president Corazon C. Aquino, and father of the 15th President Benigno S. Aquino III

- Miriam Defensor Santiago – first Filipino to be elected as International Criminal Court judge, Ramon Magsaysay Award recipient, member of the International Development Law Organization International Advisory Council, and former presidential candidate.[30][31]

Honorific senators

These senators have been given honorifics from historians.

- Isabelo de los Reyes – nationalist, journalist and historian known as the "Father of the Philippine Labor Movement"[32]

- Vicente Sotto – journalist known as the "Father of Cebuano Journalism"[33]

Milestone senators

Aside from Manuel Roxas, who was the first Filipino to have served as chief of both the Senate and the House of Representatives, and Marcelo Fernan, the first and only Filipino to have served as chief of the Senate and the judiciary, these senators below have garnered historic firsts or records in the chamber.

- Hadji Butu – first Muslim senator

- Loi Ejercito – first, and to date only, former First Lady to become a Senator

- Risa Hontiveros – first social democratic politician to be elected to the Senate and the first female Senate Deputy Minority Leader

- Eva Estrada Kalaw – first woman senator to be re-elected

- Loren Legarda – first female Senate Majority Leader and the second female Senate President Pro Tempore

- Geronima Pecson – first woman senator of the Philippines

- Santanina Rasul – first Muslim woman elected to the Senate

- Tecla San Andres Ziga – first woman Bar topnotcher in the Philippines

- Tito Sotto – longest-serving senator (24 years and counting: 1992–2004, 2010–2022, 2025–present), first five-term senator

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads