Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Sogdia

Ancient Iranian civilization From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

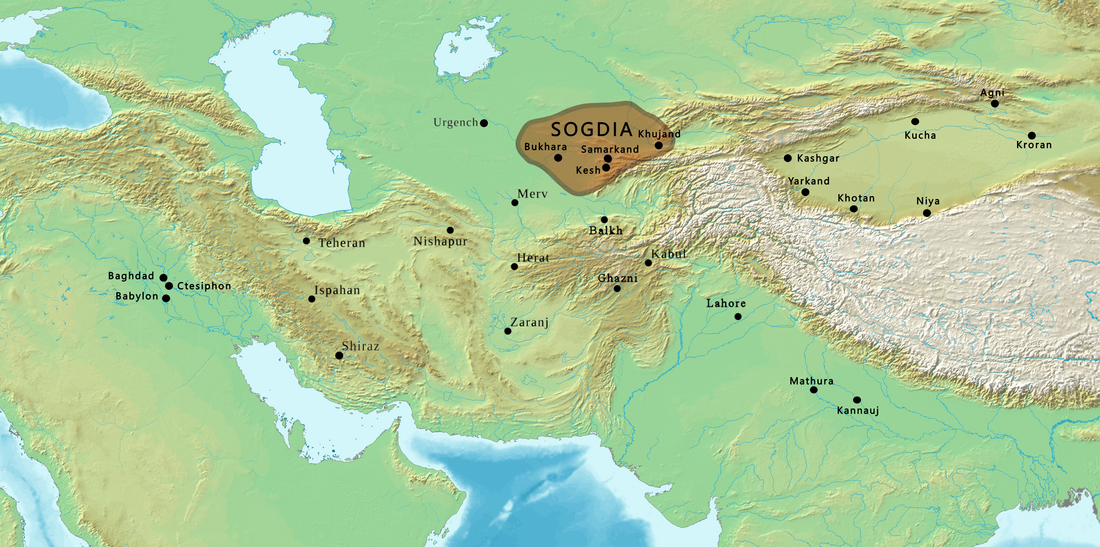

Sogdia (/ˈsɒɡdiə/) or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya rivers, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also a province of the Achaemenid Empire, and listed on the Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great. Sogdiana was first conquered by Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, and then was annexed by the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great in 328 BC. It would continue to change hands under the Seleucid Empire, the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, the Kushan Empire, the Sasanian Empire, the Hephthalite Empire, the Western Turkic Khaganate, and the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.

The Sogdian city-states, although never politically united, were centered on the city of Samarkand. Sogdian, an Eastern Iranian language, is no longer spoken. However, a descendant of one of its dialects, Yaghnobi, is still spoken by the Yaghnobis of Tajikistan. It was widely spoken in Central Asia as a lingua franca and served as one of the First Turkic Khaganate's court languages for writing documents.

Sogdians also lived in Imperial China and rose to prominence in the military and government of the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907 AD). Sogdian merchants and diplomats travelled as far west as the Byzantine Empire. They played an essential part as middlemen in the Silk Road trade route. While initially practicing the faiths of Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Buddhism and, to a lesser extent, the Church of the East from West Asia, the gradual conversion to Islam among the Sogdians and their descendants began with the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana in the 8th century. The Sogdian conversion to Islam was virtually complete by the end of the Samanid Empire in 999, coinciding with the decline of the Sogdian language, as it was largely supplanted by New Persian.

Remove ads

Geography

Sogdiana lay north of Bactria, east of Khwarezm, and southeast of Kangju between the Oxus (Amu Darya) and the Jaxartes (Syr Darya), including the fertile valley of the Zeravshan (called the Polytimetus by the ancient Greeks).[4] Sogdian territory corresponds to the modern regions of Samarkand and Bukhara in modern Uzbekistan, as well as the Sughd region of modern Tajikistan. In the High Middle Ages, Sogdian cities included sites stretching towards Issyk Kul, such as that at the archeological site of Suyab.

Remove ads

Name

Summarize

Perspective

Oswald Szemerényi devotes a thorough discussion to the etymologies of ancient ethnic words for the Scythians in his work Four Old Iranian Ethnic Names: Scythian – Skudra – Sogdian – Saka. In it, the names provided by the Greek historian Herodotus and the names of his title, except Saka, as well as many other words for "Scythian", such as Assyrian Aškuz and Greek Skuthēs, descend from *skeud-, an ancient Indo-European root meaning "propel, shoot" (cf. English shoot).[5] *skud- is the zero-grade; that is, a variant in which the -e- is not present. The restored Scythian name is *Skuδa (archer), which among the Pontic or Royal Scythians became *Skula, in which the δ has been regularly replaced by an l. According to Szemerényi, Sogdiana (Old Persian: Suguda-; Uzbek: Sug'd, Sug'diyona; Persian: سغد, romanized: Soġd; Tajik: Суғд, سغد, romanized: Suġd; Chinese: 粟特; Greek: Σογδιανή, romanized: Sogdianē) was named from the Skuδa form. Starting from the names of the province given in Old Persian inscriptions, Sugda and Suguda, and the knowledge derived from Middle Sogdian that Old Persian -gd- applied to Sogdian was pronounced as voiced fricatives, -γδ-, Szemerényi arrives at *Suγδa as an Old Sogdian endonym.[6] Applying sound changes apparent in other Sogdian words and inherent in Indo-European, he traces the development of *Suγδa from Skuδa, "archer", as follows: Skuδa > *Sukuda by anaptyxis > *Sukuδa > *Sukδa (syncope) > *Suγδa (assimilation).[7]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Prehistory

Sogdiana possessed a Bronze Age urban culture: original Bronze Age towns appear in the archaeological record beginning with the settlement at Sarazm, Tajikistan, spanning as far back as the 4th millennium BC, and then at Kök Tepe, near modern-day Bulungur, Uzbekistan, from at least the 15th century BC.[8]

Young Avestan period (c. 900–500 BC)

In the Avesta, namely in the Mihr Yasht and the Vendidad, the toponym of Gava (gava-, gāum) is mentioned as the land of the Sogdians. Gava is, therefore, interpreted as referring to Sogdia during the time of the Avesta.[9] Although there is no universal consensus on the chronology of the Avesta, most scholars today argue for an early chronology, which would place the composition of Young Avestan texts like the Mihr Yasht and the Vendiad in the first half of the first millennium BCE.[10]

The first mention of Gava is found in the Mihr Yasht, ie., the hymn dedicated to the Zoroastrian deity Mithra. In verse 10.14 it is described how Mithra reaches Mount Hara and looks at the entirety of the Airyoshayan (airiio.shaiianem, 'lands of the Arya'),

— Mihr Yasht 10.14 (translated by Ilya Gershovitch).[11]

The second mention is found in the first chapter of the Vendidad, which consists of a list of the sixteen good regions created by Ahura Mazda for the Iranians. Gava is the second region mentioned on the list, directly behind Airyanem Vaejah, the homeland of Zarathustra and the Iranians, according to Zoroastrian tradition:

The second of the good lands and countries which I, Ahura Mazda, created, was the Gava of the Sogdians (gāum yim suγδō.shaiianəm).

Thereupon came Angra Mainyu, who is all death, and he counter-created the locust, which brings death unto cattle and plants.

— Vendidad 1.4 (translated by James Darmesteter).[12]

While it is widely accepted that Gava referred to the region inhabited by the Sogdians during the Avestan period, its meaning is not clear.[13] For example, Vogelsang connects it with Gabae, a Sogdian stronghold in western Sogdia and speculates that during the time of the Avesta, the center of Sogdia may have been closer to Bukhara instead of Samarkand.[14]

Achaemenid period (546–327 BC)

Achaemenid ruler Cyrus the Great conquered Sogdiana while campaigning in Central Asia in 546–539 BC,[15] a fact mentioned by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus in his Histories.[16] Darius I introduced the Aramaic writing system and coin currency to Central Asia, in addition to incorporating Sogdians into his standing army as regular soldiers and cavalrymen.[17] Sogdia was also listed on the Behistun Inscription of Darius.[18][19][20] A contingent of Sogdian soldiers fought in the main army of Xerxes I during his second, ultimately-failed invasion of Greece in 480 BC.[20][21] A Persian inscription from Susa claims that the palace there was adorned with lapis lazuli and carnelian originating from Sogdiana.[20]

During this period of Persian rule, the western half of Asia Minor was part of the Greek civilization. As the Achaemenids conquered it, they met persistent resistance and revolt. One of their solutions was to ethnically cleanse rebelling regions, relocating those who survived to the far side of the empire. Thus Sogdiana came to have a significant Greek population.

Given the absence of any named satraps (i.e. Achaemenid provincial governors) for Sogdiana in historical records, modern scholarship has concluded that Sogdiana was governed from the satrapy of nearby Bactria.[22] The satraps were often relatives of the ruling Persian kings, especially sons who were not designated as the heir apparent.[16] Sogdiana likely remained under Persian control until roughly 400 BC, during the reign of Artaxerxes II.[23] Rebellious states of the Persian Empire took advantage of the weak Artaxerxes II, and some, such as Egypt, were able to regain their independence. Persia's massive loss of Central Asian territory is widely attributed to the ruler's lack of control. However, unlike Egypt, which was quickly recaptured by the Persian Empire, Sogdiana remained independent until it was conquered by Alexander the Great. When the latter invaded the Persian Empire, Pharasmanes, an already independent king of Khwarezm, allied with the Macedonians and sent troops to Alexander in 329 BC for his war against the Scythians of the Black Sea region (even though this anticipated campaign never materialized).[23]

During the Achaemenid period (550–330 BC), the Sogdians lived as a nomadic people much like the neighboring Yuezhi, who spoke Bactrian, an Indo-Iranian language closely related to Sogdian,[24] and were already engaging in overland trade. Some of them had also gradually settled the land to engage in agriculture.[25] Similar to how the Yuezhi offered tributary gifts of jade to the emperors of China, the Sogdians are recorded in Persian records as submitting precious gifts of lapis lazuli and carnelian to Darius I, the Persian king of kings.[25] Although the Sogdians were at times independent and living outside the boundaries of large empires, they never formed a great empire of their own like the Yuezhi, who established the Kushan Empire (30–375 AD) of Central and South Asia.[25]

Hellenistic period (327–145 BC)

Top: painted clay and alabaster head of a Zoroastrian priest wearing a distinctive Bactrian-style headdress, Takhti-Sangin, Tajikistan, 3rd–2nd century BC.

Bottom: a barbaric copy of a coin of the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus I, from the region of Sogdiana; the legend on the reverse is in Aramaic script.

Bottom: a barbaric copy of a coin of the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus I, from the region of Sogdiana; the legend on the reverse is in Aramaic script.

A now-independent and warlike Sogdiana formed a border region insulating the Achaemenid Persians from the nomadic Scythians to the north and east.[26] It was led at first by Bessus, the Achaemenid satrap of Bactria. After assassinating Darius III in his flight from the Macedonian Greek army,[27][28] he became claimant to the Achaemenid throne. The Sogdian Rock or Rock of Ariamazes, a fortress in Sogdiana, was captured in 327 BC by the forces of Alexander the Great, the basileus of Macedonian Greece, and conqueror of the Persian Achaemenid Empire.[29] Oxyartes, a Sogdian nobleman of Bactria, had hoped to keep his daughter Roxana safe at the fortress of the Sogdian Rock, yet after its fall Roxana was soon wed to Alexander as one of his several wives.[30] Roxana, a Sogdian whose name Roshanak means "little star",[31][32][33] was the mother of Alexander IV of Macedon, who inherited his late father's throne in 323 BC (although the empire was soon divided in the Wars of the Diadochi).[34]

After an extended campaign putting down Sogdian resistance and founding military outposts manned by his Macedonian veterans, Alexander united Sogdiana with Bactria into one satrapy. The Sogdian nobleman and warlord Spitamenes (370–328 BC), allied with Scythian tribes, led an uprising against Alexander's forces. This revolt was put down by Alexander and his generals Amyntas, Craterus, and Coenus, with the aid of native Bactrian and Sogdian troops.[35] With the Scythian and Sogdian rebels defeated, Spitamenes was allegedly betrayed by his own wife and beheaded.[36] Pursuant with his own marriage to Roxana, Alexander encouraged his men to marry Sogdian women in order to discourage further revolt.[30][37] This included Apama, daughter of the rebel Spitamenes, who wed Seleucus I Nicator and bore him a son and future heir to the Seleucid throne.[38] According to the Roman historian Appian, Seleucus I named three new Hellenistic cities in Asia after her (see Apamea).[38][39]

The military power of the Sogdians never recovered. Subsequently, Sogdiana formed part of the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a breakaway state from the Seleucid Empire founded in 248 BC by Diodotus I, for roughly a century.[40][41] Euthydemus I, a former satrap of Sogdiana, seems to have held the Sogdian territory as a rival claimant to the Greco-Bactrian throne; his coins were later copied locally and bore Aramaic inscriptions.[42] The Greco-Bactrian king Eucratides I may have recovered sovereignty of Sogdia temporarily.

Saka and Kushan periods (146 BC–260 AD)

Finally Sogdia was occupied by nomads when the Sakas overran the Greco-Bactrian kingdom around 145 BC, soon followed by the Yuezhi, the nomadic predecessors of the Kushans. From then until about 40 BC the Yuezhi tepidly minted coins imitating and still bearing the images of the Greco-Bactrian kings Eucratides I and Heliocles I.[46]

The Yuezhis were visited in Transoxiana by a Chinese mission, led by Zhang Qian in 126 BC,[47] which sought an offensive alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu. Zhang Qian, who spent a year in Transoxiana and Bactria, wrote a detailed account in the Shiji, which gives considerable insight into the situation in Central Asia at the time.[48] The request for an alliance was denied by the son of the slain Yuezhi king, who preferred to maintain peace in Transoxiana rather than seek revenge.

Zhang Qian also reported:

the Great Yuezhi live 2,000 or 3,000 li [832–1,247 kilometers] west of Dayuan, north of the Gui [Oxus ] river. They are bordered on the south by Daxia [Bactria], on the west by Anxi [Parthia], and on the north by Kangju [beyond the middle Jaxartes/Syr Darya]. They are a nation of nomads, moving from place to place with their herds, and their customs are like those of the Xiongnu. They have some 100,000 or 200,000 archer warriors.

— Shiji, 123[50]

From the 1st century AD, the Yuezhi morphed into the powerful Kushan Empire, covering an area from Sogdia to eastern India. The Kushan Empire became the center of the profitable Central Asian commerce. They began minting unique coins bearing the faces of their own rulers.[46] They are related to have collaborated militarily with the Chinese against nomadic incursion, particularly when they allied with the Han dynasty general Ban Chao against the Sogdians in 84, when the latter were trying to support a revolt by the king of Kashgar.[51]

- Battle scenes between "Kangju" Saka warriors, from the Orlat plaques. 1st century CE.[52]

- Orlat plaque hunter.

- Model of a Saka cataphract armour with neck-guard, from Khalchayan. 1st century BCE. Museum of Arts of Uzbekistan, nb 40.[53]

Sasanian satrapy (260–479 AD)

Historical knowledge about Sogdia is somewhat hazy during the period of the Parthian Empire (247 BC – 224 AD) in Persia.[54][55] The subsequent Sasanian Empire of Persia conquered and incorporated Sogdia as a satrapy in 260,[54] an inscription dating to the reign of Shapur I claiming "Sogdia, to the mountains of Tashkent" as his territory, and noting that its limits formed the northeastern Sasanian borderlands with the Kushan Empire.[55] However, by the 5th century the region was captured by the rival Hephthalite Empire.[54]

Hephthalite conquest of Sogdiana (479–557 AD)

on the reverse.[56]

on the reverse.[56]The Hephthalites conquered the territory of Sogdiana, and incorporated it into their Empire, around 479 AD, as this is the date of the last known independent embassy of the Sogdians to China.[57][58]

The Hephthalites may have built major fortified Hippodamian cities (rectangular walls with an orthogonal network of streets) in Sogdiana, such as Bukhara and Panjikent, as they had also in Herat, continuing the city-building efforts of the Kidarites.[58] The Hephthalites probably ruled over a confederation of local rulers or governors, linked through alliance agreements. One of these vassals may have been Asbar, ruler of Vardanzi, who also minted his own coinage during the period.[59]

The wealth of the Sasanian ransoms and tributes to the Hephthalites may have been reinvested in Sogdia, possibly explaining the prosperity of the region from that time.[58] Sogdia, at the center of a new Silk Road between China to the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire became extremely prosperous under its nomadic elites.[60] The Hephthalites took on the role of major intermediary on the Silk Road, after their great predecessor the Kushans, and contracted local Sogdians to carry on the trade of silk and other luxury goods between the Chinese Empire and the Sasanian Empire.[61]

Because of the Hephthalite occupation of Sogdia, the original coinage of Sogdia came to be flooded by the influx of Sasanian coins received as a tribute to the Hephthalites. This coinage then spread along the Silk Road.[57] The symbol of the Hephthalites appears on the residual coinage of Samarkand, probably as a consequence of the Hephthalite control of Sogdia, and becomes prominent in Sogdian coinage from 500 to 700 AD, including in the coinage of their indigenous successors the Ikhshids (642–755 AD), ending with the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.[62][63]

Turkic Khaganates (557–742 AD)

The Turks of the First Turkic Khaganate and the Sasanians under Khosrow I allied against the Hephthalites and defeated them after an eight-day battle near Qarshi, the Battle of Bukhara, perhaps in 557.[64] The Turks retained the area north of the Oxus, including all of Sogdia, while the Sasanians obtained the areas south of it. The Turks fragmented in 581, and the Western Turkic Khaganate took over in Sogdia.

Archaeological remains suggest that the Turks probably became the main trading partners of the Sogdians, as appears from the tomb of the Sogdian trader An Jia.[65] The Turks also appear in great numbers in the Afrasiab murals of Samarkand, where they are probably shown attending the reception by the local Sogdian ruler Varkhuman in the 7th century AD.[66][67] These paintings suggest that Sogdia was a very cosmopolitan environment at that time, as delegates of various nations, including Chinese and Korean delegates, are also shown.[66][68] From around 650, China led the conquest of the Western Turks, and the Sogdian rulers such as Varkhuman as well as the Western Turks all became nominal vassals of China, as part of the Anxi Protectorate of the Tang dynasty, until the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.[69]

Arab Muslim conquest (8th century AD)

Letter of an Arab Emir to the Sogdian ruler Devashtich, found in Mount Mugh

Wealthy Arab, Palace of Devashtich, Penjikent murals

Umayyads (−750)

Qutayba ibn Muslim (669–716), Governor of Greater Khorasan under the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), initiated the Muslim conquest of Sogdia during the early 8th century, with the local ruler of Balkh offering him aid as an Umayyad ally.[55][70] However, when his successor al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah governed Khorasan (717–719), many native Sogdians, who had converted to Islam, began to revolt when they were no longer exempt from paying the tax on non-Muslims, the jizya, because of a new law stating that proof of circumcision and literacy in the Quran was necessary for new converts.[55][71] With the aid of the Turkic Turgesh, the Sogdians were able to expel the Umayyad Arab garrison from Samarkand, and Umayyad attempts to restore power there were rebuffed until the arrival of Sa'id ibn Amr al-Harashi (fl. 720–735). The Sogdian ruler (i.e. ikhshid) of Samarkand, Gurak, who had previously overthrown the pro-Umayyad Sogdian ruler Tarkhun in 710, decided that resistance against al-Harashi's large Arab force was pointless, and thereafter persuaded his followers to declare allegiance to the Umayyad governor.[71] Divashtich (r. 706–722), the Sogdian ruler of Panjakent, led his forces to the Zarafshan Range (near modern Zarafshan, Tajikistan), whereas the Sogdians following Karzanj, the ruler of Pai (modern Kattakurgan, Uzbekistan), fled to the Principality of Farghana, where their ruler at-Tar (or Alutar) promised them safety and refuge from the Umayyads. However, at-Tar secretly informed al-Harashi of the Sogdians hiding in Khujand, who were then slaughtered by al-Harashi's forces after their arrival.[72]

From 722, following the Muslim invasion, new groups of Sogdians, many of them Nestorian Christians, emigrated to the east, where the Turks had been more welcoming and more tolerant of their religion since the time of Sassanian religious persecutions. They particularly created colonies in the area of Semirechye, where they continued to flourish into the 10th century with the rise of the Karluks and the Kara-Khanid Khanate. These Sogdians are known for producing beautiful silver plates with Eastern Christian iconography, such as the Anikova dish.[73][74][75]

Abbasid Caliphate (750–819)

The Umayyads fell in 750 to the Abbasid Caliphate, which quickly asserted itself in Central Asia after winning the Battle of Talas (along the Talas River in modern Talas Oblast, Kyrgyzstan) in 751, against the Chinese Tang dynasty. This conflict incidentally introduced Chinese papermaking to the Islamic world.[77] The cultural consequences and political ramifications of this battle meant the retreat of the Chinese empire from Central Asia. It also allowed for the rise of the Samanid Empire (819–999), a Persian state centered at Bukhara (in what is now modern Uzbekistan) that nominally observed the Abbasids as their overlords, yet retained a great deal of autonomy and upheld the mercantile legacy of the Sogdians.[77] Yet the Sogdian language gradually declined in favor of the Persian language of the Samanids (the ancestor to the modern Tajik language), the spoken language of renowned poets and intellectuals of the age such as Ferdowsi (940–1020).[77] So too did the original religions of the Sogdians decline; Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Manichaeism, and Nestorian Christianity disappeared in the region by the end of the Samanid period.[77] The Samanids were also responsible for converting the surrounding Turkic peoples to Islam.

Samanids (819–999)

The Samanids occupied the Sogdian region from circa 819 until 999, establishing their capital at Samarkand (819–892) and then at Bukhara (892–999).

Turkic conquests: Kara-Khanid Khanate (999–1212)

In 999 the Samanid Empire was conquered by an Islamic Turkic power, the Kara-Khanid Khanate (840–1212).[81]

From 1212, the Kara-Khanids in Samarkand were conquered by the Kwarazmians. Soon however, Khwarezmia was invaded by the early Mongol Empire and its ruler Genghis Khan destroyed the once vibrant cities of Bukhara and Samarkand.[82] However, in 1370, Samarkand saw a revival as the capital of the Timurid Empire. The Turko-Mongol ruler Timur brought about the forced immigration to Samarkand of artisans and intellectuals from across Asia, transforming it not only into a trade hub but also into one of the most important cities of the Islamic world.[83]

Remove ads

Economy and diplomacy

Summarize

Perspective

Central Asia and the Silk Road

Most merchants did not travel the entire Silk Road, but would trade goods through middlemen based in oasis towns, such as Khotan or Dunhuang. The Sogdians, however, established a trading network across the 1500 miles from Sogdiana to China. In fact, the Sogdians turned their energies to trade so thoroughly that the Saka of the Kingdom of Khotan called all merchants suli, "Sogdian", whatever their culture or ethnicity.[84] The Sogdians had learnt to become expert traders from the Kushans, together with whom they initially controlled trade in the Ferghana Valley and Kangju during the 'birth' of the Silk Road. Later, they became the primary middlemen after the demise of the Kushan Empire.[85][86]

Unlike the empires of antiquity, the Sogdian region was not a territory confined within fixed borders, but rather a network of city-states, from one oasis to another, linking Sogdiana to Byzantium, India, Indochina and China.[87] Sogdian contacts with China were initiated by the embassy of the Chinese explorer Zhang Qian during the reign of Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BC) of the former Han dynasty. Zhang wrote a report of his visit to the Western Regions in Central Asia and named the area of Sogdiana as "Kangju".[88]

Left image: Sogdian men feasting and eating at a banquet, from a wall mural of Panjakent, Tajikistan, 7th century AD

Right image: Detail of a mural from Varakhsha, 6th century AD, showing elephant riders fighting tigers and monsters.

Right image: Detail of a mural from Varakhsha, 6th century AD, showing elephant riders fighting tigers and monsters.

Following Zhang Qian's embassy and report, commercial Chinese relations with Central Asia and Sogdiana flourished,[47] as many Chinese missions were sent throughout the 1st century BC. In his Shiji published in 94 BC, Chinese historian Sima Qian remarked that "the largest of these embassies to foreign states numbered several hundred persons, while even the smaller parties included over 100 members ... In the course of one year anywhere from five to six to over ten parties would be sent out."[89] In terms of the silk trade, the Sogdians also served as middlemen between the Chinese Han Empire and the Parthian Empire of the Middle East and West Asia.[90] Sogdians played a major role in facilitating trade between China and Central Asia along the Silk Roads as late as the 10th century, their language serving as a lingua franca for Asian trade as far back as the 4th century.[91][92]

Left image: An Jia, a Sogdian trader and official in China, depicted on his tomb in 579 AD.

Right image: ceramic figurine of a Sogdian merchant in northern China, Tang dynasty, 7th century AD

Right image: ceramic figurine of a Sogdian merchant in northern China, Tang dynasty, 7th century AD

Left image: Sogdian coin, 6th century, British Museum

Right image: Chinese-influenced Sogdian coin, from Kelpin, 8th century, British Museum

Right image: Chinese-influenced Sogdian coin, from Kelpin, 8th century, British Museum

Subsequent to their domination by Alexander the Great, the Sogdians from the city of Marakanda (Samarkand) became dominant as traveling merchants, occupying a key position along the ancient Silk Road.[93] They played an active role in the spread of faiths such as Manicheism, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism along the Silk Road. The Chinese Sui Shu (Book of Sui) describes Sogdians as "skilled merchants" who attracted many foreign traders to their land to engage in commerce.[94] They were described by the Chinese as born merchants, learning their commercial skills at an early age. It appears from sources, such as documents found by Sir Aurel Stein and others, that by the 4th century they may have monopolized trade between India and China. A letter written by Sogdian merchants dated 313 AD and found in the ruins of a watchtower in Gansu, was intended to be sent to merchants in Samarkand, warning them that after Liu Cong of Han-Zhao sacked Luoyang and the Jin emperor fled the capital, there was no worthwhile business there for Indian and Sogdian merchants.[21][95] Furthermore, in 568 AD, a Turko-Sogdian delegation travelled to the Roman emperor in Constantinople to obtain permission to trade and in the following years commercial activity between the states flourished.[96] Put simply, the Sogdians dominated trade along the Silk Road from the 2nd century BC until the 10th century.[84]

Suyab and Talas in modern-day Kyrgyzstan were the main Sogdian centers in the north that dominated the caravan routes of the 6th to 8th centuries.[97] Their commercial interests were protected by the resurgent military power of the Göktürks, whose empire was built on the political power of the Ashina clan and economic clout of the Sogdians.[98][99][100] Sogdian trade, with some interruptions, continued into the 9th century. For instance, camels, women, girls, silver, and gold were seized from Sogdia during a raid by Qapaghan Qaghan (692–716), ruler of the Second Turkic Khaganate.[101] In the 10th century, Sogdiana was incorporated into the Uighur Empire, which until 840 encompassed northern Central Asia. This khaganate obtained enormous deliveries of silk from Tang China in exchange for horses, in turn relying on the Sogdians to sell much of this silk further west.[102] Peter B. Golden writes that the Uyghurs not only adopted the writing system and religious faiths of the Sogdians, such as Manichaeism, Buddhism, and Christianity, but also looked to the Sogdians as "mentors", while gradually replacing them in their roles as Silk Road traders and purveyors of culture.[103] Muslim geographers of the 10th century drew upon Sogdian records dating to 750–840. After the end of the Uyghur Empire, Sogdian trade underwent a crisis. Following the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana in the 8th century, the Samanids resumed trade on the northwestern road leading to the Khazars and the Urals and the northeastern one toward the nearby Turkic tribes.[99]

During the 5th and 6th century, many Sogdians took up residence in the Hexi Corridor, where they retained autonomy in terms of governance and had a designated official administrator known as a Sabao, which suggests their importance to the socioeconomic structure of China. The Sogdian influence on trade in China is also made apparent by a Chinese document which lists taxes paid on caravan trade in the Turpan region and shows that twenty-nine out of the thirty-five commercial transactions involved Sogdian merchants, and in thirteen of those cases both the buyer and the seller were Sogdian.[104] Trade goods brought to China included grapes, alfalfa, and Sassanian silverware, as well as glass containers, Mediterranean coral, brass Buddhist images, Roman wool cloth, and Baltic amber. These were exchanged for Chinese paper, copper, and silk.[84] In the 7th century, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang noted with approval that Sogdian boys were taught to read and write at the age of five, though their skill was turned to trade, disappointing the scholarly Xuanzang. He also recorded the Sogdians working in other capacities such as farmers, carpetweavers, glassmakers, and woodcarvers.[105]

Trade and diplomacy with the Byzantine Empire

Shortly after the smuggling of silkworm eggs into the Byzantine Empire from China by Nestorian Christian monks, the 6th-century Byzantine historian Menander Protector writes of how the Sogdians attempted to establish a direct trade of Chinese silk with the Byzantine Empire. After forming an alliance with the Sasanian ruler Khosrow I to defeat the Hephthalite Empire, Istämi, the Göktürk ruler of the First Turkic Khaganate, was approached by Sogdian merchants requesting permission to seek an audience with the Sassanid king of kings for the privilege of traveling through Persian territories in order to trade with the Byzantines.[90] Istämi refused the first request, but when he sanctioned the second one and had the Sogdian embassy sent to the Sassanid king, the latter had the members of the embassy poisoned.[90] Maniah, a Sogdian diplomat, convinced Istämi to send an embassy directly to Byzantium's capital Constantinople, which arrived in 568 and offered not only silk as a gift to Byzantine ruler Justin II, but also proposed an alliance against Sassanid Persia. Justin II agreed and sent an embassy to the Turkic Khaganate, ensuring the direct silk trade desired by the Sogdians.[90][106][107]

It appears, however, that direct trade with the Sogdians remained limited in light of the small amount of Roman and Byzantine coins found in Central Asian and Chinese archaeological sites belonging to this era. Although Roman embassies apparently reached Han China from 166 AD onwards,[108] and the ancient Romans imported Han Chinese silk while the Han dynasty Chinese imported Roman glasswares as discovered in their tombs,[109][110] Valerie Hansen (2012) wrote that no Roman coins from the Roman Republic (507–27 BC) or the Principate (27 BC – 330 AD) era of the Roman Empire have been found in China.[111] However, Warwick Ball (2016) upends this notion by pointing to a hoard of sixteen Roman coins found at Xi'an, China (formerly Chang'an), dated to the reigns of various emperors from Tiberius (14–37 AD) to Aurelian (270–275 AD).[112] The earliest gold solidus coins from the Eastern Roman Empire found in China date to the reign of Byzantine emperor Theodosius II (r. 408–450) and altogether only forty-eight of them have been found (compared to thirteen-hundred silver coins) in Xinjiang and the rest of China.[111] The use of silver coins in Turfan persisted long after the Tang campaign against Karakhoja and Chinese conquest of 640, with a gradual adoption of Chinese bronze coinage over the course of the 7th century.[111] The fact that these Eastern Roman coins were almost always found with Sasanian Persian silver coins and Eastern Roman gold coins were used more as ceremonial objects like talismans, confirms the pre-eminent importance of Greater Iran in Chinese Silk Road commerce of Central Asia compared to Eastern Rome.[113]

Sogdian traders in the Tarim Basin

The Kizil Caves near Kucha, mid-way in the Tarim Basin, record many scenes of traders from Central Asia in the 5–6th century: these combine influence from the Eastern Iran sphere, at that time occupied by the Sasanian Empire and the Hephthalites, with strong Sogdian cultural elements.[114][115] Sogdia, at the center of a new Silk Road between China to the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire became extremely prosperous around that time.[116]

The style of this period in Kizil is characterized by strong Iranian-Sogdian elements probably brought with intense Sogdian-Tocharian trade, the influence of which is especially apparent in the Central-Asian caftans with Sogdian textile designs, as well as Sogdian longswords of many of the figures.[117] Other characteristic Sogdian designs are animals, such as ducks, within pearl medallions.[117]

- Dragon-King Mabi saving traders, Cave 14, Kizil Caves

- Two-headed dragon capturing traders, Cave 17

- Sab leading the way for the 500 traders, Kizil Cave 17.

Sogdian merchants, generals, and statesmen in Imperial China

Left image: kneeling Sogdian donors to the Buddha (fresco, with detail), Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves, near Turpan in the eastern Tarim Basin, China, 8th century

Right image: Sogdians having a toast, with females wearing Chinese headdresses. Anyang funerary bed, 550–577 AD.[118]

Right image: Sogdians having a toast, with females wearing Chinese headdresses. Anyang funerary bed, 550–577 AD.[118]

Aside from the Sogdians of Central Asia who acted as middlemen in the Silk Road trade, other Sogdians settled down in China for generations. Many Sogdians lived in Luoyang, capital of the Jin dynasty (266–420), but fled following the collapse of the Jin dynasty's control over northern China in 311 AD and the rise of northern nomadic tribes.[95]

Aurel Stein discovered 5 letters written in Sogdian known as the "Ancient Letters" in an abandoned watchtower near Dunhuang in 1907. One of them was written by a Sogdian woman named Miwnay who had a daughter named Shayn and she wrote to her mother Chatis in Sogdia. Miwnay and her daughter were abandoned in China by Nanai-dhat, her husband who was also Sogdian like her. Nanai-dhat refused to help Miwnay and their daughter after forcing them to come with him to Dunhuang and then abandoning them, telling them they should serve the Han Chinese. Miwnay asked one of her husband's relative Artivan and then asked another Sogdian man, Farnkhund to help them but they also abandoned them. Miwnay and her daughter Shayn were then forced to became servants of Han Chinese after living on charity from a priest. Miwnay cursed her Sogdian husband for leaving her, saying she would rather have been married to a pig or dog.[119][120][121][122][123][124][125][126][127] Another letter in the collection was written by the Sogdian Nanai-vandak addressed to Sogdians back home in Samarkand informing them about a mass rebellion by Xiongnu Hun rebels against their Han Chinese rulers of the Western Jin dynasty informing his people that every single one of the diaspora Sogdians and Indians in the Chinese Western Jin capital Luoyang died of starvation due to the uprising by the rebellious Xiongnu, who were formerly subjects of the Han Chinese. The Han Chinese emperor abandoned Luoyang when it came under siege by the Xiongnu rebels and his palace was burned down. Nanai-vandak also said the city of Ye was no more as the Xiongnu rebellion resulted in disaster for the Sogdian diaspora in China.[128][129] Han Chinese men frequently bought Sogdian slave girls for sexual relations.[130]

Still, some Sogdians continued living in Gansu.[95] A community of Sogdians remained in the Northern Liang capital of Wuwei, but when the Northern Liang were defeated by the Northern Wei in 439 AD, many Sogdians were forcibly relocated to the Northern Wei capital of Datong, thereby fostering exchanges and trade for the new dynasty.[133] Numerous Central Asian objects have been found in Northern Wei tombs, such as the tomb of Feng Hetu.[134]

Other Sogdians came from the west and took positions in Chinese society. The Bei shi[135] describes how a Sogdian came from Anxi (western Sogdiana or Parthia) to China and became a sabao (薩保, from Sanskrit sarthavaha, meaning caravan leader)[106] who lived in Jiuquan during the Northern Wei (386 – 535 AD), and was the ancestor of An Tugen, a man who rose from a common merchant to become a top ranking minister of state for the Northern Qi (550 – 577 AD).[94][136] Valerie Hansen asserts that around this time and extending into the Tang dynasty (618 – 907 AD), the Sogdians "became the most influential of the non-Chinese groups resident in China". Two different types of Sogdians came to China, envoys and merchants. Sogdian envoys settled, marrying Chinese women, purchasing land, with newcomers living there permanently instead of returning to their homelands in Sogdiana.[94] They were concentrated in large numbers around Luoyang and Chang'an, and also Xiangyang in present-day Hubei, building Zoroastrian temples to service their communities once they reached the threshold of roughly 100 households.[94] From the Northern Qi to Tang periods, the leaders of these communities, the sabao, were incorporated into the official hierarchy of state officials.[94]

During the 6–7th centuries AD, Sogdian families living in China created important tombs with funerary epitaphs explaining the history of their illustrious houses. Their burial practices blended both Chinese forms such as carved funerary beds with Zoroastrian sensibilities in mind, such as separating the body from both the earth and water.[137] Sogdian tombs in China are among the most lavish of the period in this country, and are only inferior to Imperial tombs, suggesting that the Sogdian Sabao were among the wealthiest members of the population.[138]

In addition to being merchants, monks, and government officials, Sogdians also served as soldiers in the Tang military.[139] An Lushan, whose father was Sogdian and mother a Gokturk, rose to the position of a military governor (jiedushi) in the northeast before leading the An Lushan Rebellion (755 – 763 AD), which split the loyalties of the Sogdians in China.[139] The An Lushan rebellion was supported by many Sogdians, and in its aftermath many of them were slain or changed their names to escape their Sogdian heritage, so that little is known about the Sogdian presence in North China since that time.[140] The former Yan rebel general Gao Juren of Goguryeo descent ordered a mass slaughter of West Asian (Central Asian) Sogdians in Fanyang, also known as Jicheng (Beijing), in Youzhou identifying them through their big noses and lances were used to impale their children when he rebelled against the rebel Yan emperor Shi Chaoyi and defeated rival Yan dynasty forces under the Turk Ashina Chengqing,[141][142] High nosed Sogdians were slaughtered in Youzhou in 761. Youzhou had Linzhou, another "protected" prefecture attached to it and Sogdians lived there in great numbers.[143][144] because Gao Juren, like Tian Shengong wanted to defect to the Tang dynasty and wanted them to publicly recognize and acknowledge him as a regional warlord and offered the slaughter of the Central Asian Hu "barbarians" as a blood sacrifice for the Tang court to acknowledge his allegiance without him giving up territory. according to the book, "History of An Lushan" (安祿山史記).[145][146] Another source says the slaughter of the Hu barbarians serving Ashina Chengqing was done by Gao Juren in Fanyang in order to deprive him of his support base, since the Tiele, Tongluo, Sogdians and Turks were all Hu and supported the Turk Ashina Chengqing against the Mohe, Xi, Khitan and Goguryeo origin soldiers led by Gao Juren. Gao Juren was later killed by Li Huaixian, who was loyal to Shi Chaoyi.[147][148] A massacre of foreign Arab and Persian Muslim merchants by former Yan rebel general Tian Shengong happened during the An Lushan rebellion in the Yangzhou massacre (760),[149][150] since Tian Shengong was defecting to the Tang dynasty and wanted them to publicly recognized and acknowledge him, and the Tang court portrayed the war as between rebel hu barbarians of the Yan against Han Chinese of the Tang dynasty, Tian Shengong slaughtered foreigners as a blood sacrifice to prove he was loyal to the Han Chinese Tang dynasty state and for them to recognize him as a regional warlord without him giving up territory, and he killed other foreign Hu barbarian ethnicities as well whose ethnic groups were not specified, not only Arabs and Persians since it was directed against all foreigners.[151][152]

Sogdians continued as active traders in China following the defeat of the rebellion, but many of them were compelled to hide their ethnic identity. A prominent case was An Chongzhang, Minister of War, and Duke of Liang who, in 756, asked Emperor Suzong of Tang to allow him to change his name to Li Baoyu because of his shame in sharing the same surname with the rebel leader.[139] This change of surnames was enacted retroactively for all of his family members, so that his ancestors would also be bestowed the surname Li.[139]

The Nestorian Christians like the Bactrian Priest Yisi of Balkh helped the Tang dynasty general Guo Ziyi militarily crush the An Lushan rebellion, with Yisi personally acting as a military commander and Yisi and the Nestorian Church of the East were rewarded by the Tang dynasty with titles and positions as described in the Nestorian Stele.[153][154][155][156][157][158]

Amoghavajra used his rituals against An Lushan while staying in Chang'an when it was occupied in 756 while the Tang dynasty crown prince and Xuanzong emperor had retreated to Sichuan. Amoghavajra's rituals were explicitly intended to introduced death, disaster and disease against An Lushan.[159] As a result of Amoghavajrya's assistance in crushing An Lushan, Estoteric Buddhism became the official state Buddhist sect supported by the Tang dynasty, "Imperial Buddhism" with state funding and backing for writing scriptures, and constructing monasteries and temples. The disciples of Amoghavajra did ceremonies for the state and emperor.[160] Tang dynasty Emperor Suzong was crowned as cakravartin by Amoghavajra after victory against An Lushan in 759 and he had invoked the Acala vidyaraja against An Lushan. The Tang dynasty crown prince Li Heng (later Suzong) also received important strategic military information from Chang'an when it was occupied by An Lushan though secret message sent by Amoghavajra.[161]

Epitaphs were found dating from the Tang dynasty of a Christian couple in Luoyang of a Nestorian Christian Sogdian woman, who Lady An (安氏) who died in 821 and her Nestorian Christian Han Chinese husband, Hua Xian (花献) who died in 827. These Han Chinese Christian men may have married Sogdian Christian women because of a lack of Han Chinese women belonging to the Christian religion, limiting their choice of spouses among the same ethnicity.[162] Another epitaph in Luoyang of a Nestorian Christian Sogdian woman also surnamed An was discovered and she was put in her tomb by her military officer son on 22 January 815. This Sogdian woman's husband was surnamed He (和) and he was a Han Chinese man and the family was indicated to be multiethnic on the epitaph pillar.[163] In Luoyang, the mixed raced sons of Nestorian Christian Sogdian women and Han Chinese men has many career paths available for them. Neither their mixed ethnicity nor their faith were barriers and they were able to become civil officials, a military officers and openly celebrated their Christian religion and support Christian monasteries.[164]

During the Tang and subsequent Five Dynasties and Song dynasty, a large community of Sogdians also existed in the multicultural entrepôt of Dunhuang, Gansu, a major center of Buddhist learning and home to the Buddhist Mogao Caves.[165] Although Dunhuang and the Hexi Corridor were captured by the Tibetan Empire after the An Lushan Rebellion, in 848 the ethnic Han Chinese general Zhang Yichao (799–872) managed to wrestle control of the region from the Tibetans during their civil war, establishing the Guiyi Circuit under Emperor Xuānzong of Tang (r. 846–859).[166][167] Although the region occasionally fell under the rule of different states, it retained its multilingual nature as evidenced by an abundance of manuscripts (religious and secular) in Chinese and Tibetan, but also Sogdian, Khotanese (another Eastern Iranian language native to the region), Uyghur, and Sanskrit.[168]

There were nine prominent Sogdian clans (昭武九姓). The names of these clans have been deduced from the Chinese surnames listed in a Tang-era Dunhuang manuscript (Pelliot chinois 3319V).[169] Each "clan" name refers to a different city-state as the Sogdian used the name of their hometown as their Chinese surname.[170] Of these the most common Sogdian surname throughout China was Shí (石, generally given to those from Chach, modern Tashkent). The following surnames also appear frequently on Dunhuang manuscripts and registers: Shǐ (史, from Kesh, modern Shahrisabz), An (安, from Bukhara), Mi (米, from Panjakent), Kāng (康, from Samarkand), Cáo (曹, from Kabudhan, north of the Zeravshan River), and Hé (何, from Kushaniyah).[169][171] Confucius is said to have expressed a desire to live among the "nine tribes" which may have been a reference to the Sogdian community.[172]

The influence of Sinicized and multilingual Sogdians during this Guiyijun (歸義軍) period (c. 850 – c. 1000 AD) of Dunhuang is evident in a large number of manuscripts written in Chinese characters from left to right instead of vertically, mirroring the direction of how the Sogdian alphabet is read.[173] Sogdians of Dunhuang also commonly formed and joined lay associations among their local communities, convening at Sogdian-owned taverns in scheduled meetings mentioned in their epistolary letters.[174] Sogdians living in Turfan under the Tang dynasty and Gaochang Kingdom engaged in a variety of occupations that included: farming, military service, painting, leather crafting and selling products such as iron goods.[169] The Sogdians had been migrating to Turfan since the 4th century, yet the pace of migration began to climb steadily with the Muslim conquest of Persia and Fall of the Sasanian Empire in 651, followed by the Islamic conquest of Samarkand in 712.[169]

Remove ads

Language and culture

Summarize

Perspective

The 6th century is thought to be the peak of Sogdian culture, judging by its highly developed artistic tradition. By this point, the Sogdians were entrenched in their role as the central Asian traveling and trading merchants, transferring goods, culture and religion.[175] During the Middle Ages, the valley of the Zarafshan around Samarkand retained its Sogdian name, Samarkand.[4] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, medieval Arab geographers considered it one of the four fairest regions of the world.[4] Where the Sogdians moved in considerable numbers, their language made a considerable impact. For instance, during China's Han dynasty, the native name of the Tarim Basin city-state of Loulan was "Kroraina", possibly from Greek due to nearby Hellenistic influence.[176] However, centuries later in 664 AD, the Tang Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang labelled it as "Nafupo" (納縛溥), which according to Hisao Matsuda is a transliteration of the Sogdian word Navapa meaning "new water".[177]

Art

The Afrasiab paintings of the 6th to 7th centuries in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, offer a rare surviving example of Sogdian art. The paintings, showing scenes of daily life and events such as the arrival of foreign ambassadors, are located within the ruins of aristocratic homes. It is unclear if any of these palatial residences served as the official palace of the rulers of Samarkand.[178] The oldest surviving Sogdian monumental wall murals date to the 5th century and are located at Panjakent, Tajikistan.[179] In addition to revealing aspects of their social and political lives, Sogdian art has also been instrumental in aiding historians' understanding of their religious beliefs. For instance, it is clear that Buddhist Sogdians incorporated some of their own Iranian deities into their version of the Buddhist Pantheon. At Zhetysu, Sogdian gilded bronze plaques on a Buddhist temple show a pairing of a male and female deity with outstretched hands holding a miniature camel, a common non-Buddhist image similarly found in the paintings of Samarkand and Panjakent.[180]

Language

The Sogdians spoke an Eastern Iranian language called Sogdian, closely related to Bactrian, Khwarazmian, and the Khotanese Saka language, widely spoken Eastern Iranian languages of Central Asia in ancient times.[54][181] Sogdian was also prominent in the oasis city-state of Turfan in the Tarim Basin region of Northwest China (in modern Xinjiang).[181] Judging by the Sogdian Bugut inscription of Mongolia written c. 581, the Sogdian language was also an official language of the First Turkic Khaganate established by the Gokturks.[107][181]

Sogdian was written largely in three scripts: the Sogdian alphabet, the Syriac alphabet, and the Manichaean alphabet, each derived from the Aramaic alphabet,[182][183] which had been widely used in both the Achaemenid and Parthian empires of ancient Iran.[17][184] The Sogdian alphabet formed the basis of the Old Uyghur alphabet of the 8th century, which in turn was used to create the Mongolian script of the early Mongol Empire during the 13th century.[185] Later in 1599, the Jurchen leader Nurhaci decided to convert the Mongolian alphabet to make it suitable for the Manchu people.

The Yaghnobi people living in the Sughd province of Tajikistan still speak a descendant of the Sogdian language.[55][186] Yaghnobi is largely a continuation of the medieval Sogdian dialect from the Osrushana region of the western Fergana Valley.[187] The great majority of the Sogdian people assimilated with other local groups such as the Bactrians, Chorasmians, and Persians, and came to speak Persian. In 819, the Persian speaking population founded the Samanid Empire in the region. They are among the ancestors of the modern Tajiks. Numerous Sogdian cognates can be found in the modern Tajik language, although the latter is a Western Iranian language.

Clothing

Early medieval Sogdian costumes can be divided in two periods: Hephtalitic (5th and 6th centuries) and Turkic (7th and early 8th centuries). The latter did not become common immediately after the political dominance of the Gökturks but only in c. 620 when, especially following Western Turkic Khagan Ton-jazbgu's reforms, Sogd was Turkized and the local nobility was officially included in the Khaganate's administration.[188]

For both sexes clothes were tight-fitted, and narrow waists and wrists were appreciated. The silhouettes for grown men and young girls emphasized wide shoulders and narrowed to the waist; the silhouettes for female aristocrats were more complicated. The Sogdian clothing underwent a thorough process of Islamization in the ensuing centuries, with few of the original elements remaining. In their stead, turbans, kaftans, and sleeved coats became more common.[188]

Religious beliefs

The Sogdians practiced a variety of religious faiths. However, Zoroastrianism was most likely their main religion, as demonstrated by material evidence, such as the discovery in Samarkand, Panjakent and Er-Kurgan of murals depicting votaries making offerings before fire altars and ossuaries holding the bones of the dead – in accordance with Zoroastrian ritual. At Turfan, Sogdian burials shared similar features with traditional Chinese practices, yet they still retained essential Zoroastrian rituals, such as allowing the bodies to be picked clean by scavengers before burying the bones in ossuaries.[169] They also sacrificed animals to Zoroastrian deities, including the supreme deity Ahura Mazda.[169] Zoroastrianism remained the dominant religion among Sogdians until after the Islamic conquest, when they gradually converted to Islam, as is shown by Richard Bulliet's "conversion curve".[189]

One of the most widely worshiped deities in Sogdia was the goddess Nana, derived from the Mesopotamian goddess Nanaya, and is traditionally depicted as a 4 armed goddess riding a lion, holding the sun and moon. She and the river god Oxus were some of the most widely attested deities from the region.[190] She was regarded as a civic and astral goddess, and her sacred city was Panjikent.

Left: An 8th-century Tang dynasty Chinese clay figurine of a Sogdian man wearing a distinctive cap and face veil, a probable Zoroastrian priest engaging in a ritual at a fire temple, since face veils were used to avoid contaminating the holy fire with breath or saliva; Museum of Oriental Art (Turin), Italy.[191]

Right: A Zoroastrian fire worship ceremony, depicted on the Tomb of Anjia, a Sogdian merchant in China.[192]

Right: A Zoroastrian fire worship ceremony, depicted on the Tomb of Anjia, a Sogdian merchant in China.[192]

The Sogdian religious texts found in China and dating to the Northern dynasties, Sui, and Tang are mostly Buddhist (translated from Chinese sources), Manichaean, and Nestorian Christian, with only a small minority of Zoroastrian texts.[193] But, tombs of Sogdian merchants in China dated to the last third of the 6th century show predominantly Zoroastrian motifs or Zoroastrian-Manichaean syncretism, while archaeological remains from Sogdiana appear fairly Iranian and conservatively Zoroastrian.[193]

However, the Sogdians epitomized the religious plurality found along the trade routes. The largest body of Sogdian texts are Buddhist, and Sogdians were among the principal translators of Buddhist sutras into Chinese. However, Buddhism did not take root in Sogdiana itself.[194] Additionally, the Bulayiq monastery to the north of Turpan contained Sogdian Christian texts, and there are numerous Manichaean texts in Sogdiana from nearby Qocho.[195] The reconversion of Sogdians from Buddhism to Zoroastrianism coincided with the adoption of Zoroastrianism by the Sassanid Empire of Persia.[106] From the 4th century onwards, Sogdian Buddhist pilgrims left behind evidence of their travels along the steep cliffs of the Indus River and Hunza Valley. It was here that they carved images of the Buddha and holy stupas in addition to their full names, in hopes that the Buddha would grant them his protection.[196]

The Sogdians also practiced Manichaeism, the faith of Mani, which they spread among the Uyghurs. The Uyghur Khaganate (744–840 AD) developed close ties to Tang China once it had aided the Tang in suppressing the rebellion of An Lushan and his Göktürk successor Shi Siming, establishing an annual trade relationship of one million bolts of Chinese silk for one hundred thousand horses.[102] The Uyghurs relied on Sogdian merchants to sell much of this silk further west along the Silk Road, a symbiotic relationship that led many Uyghurs to adopt Manichaeism from the Sogdians.[102] However, evidence of Manichaean liturgical and canonical texts of Sogdian origin remains fragmentary and sparse compared to their corpus of Buddhist writings.[197] The Uyghurs were also followers of Buddhism. For instance, they can be seen wearing silk robes in the praṇidhi scenes of the Uyghur Bezeklik Buddhist murals of Xinjiang, China, particularly Scene 6 from Temple 9 showing Sogdian donors to the Buddha.[198][199]

In addition to Puranic cults, there were five Hindu deities known to have been worshipped in Sogdiana.[200] These were Brahma, Indra, Mahadeva (Shiva), Narayana, and Vaishravana; the gods Brahma, Indra, and Shiva were known by their Sogdian names Zravan, Adbad and Veshparkar, respectively.,[200] As seen in an 8th-century mural from Panjakent, portable fire altars can be "associated" with Mahadeva-Veshparkar, Brahma-Zravan, and Indra-Abdab, according to Braja Bihārī Kumar.[200]

Among the Sogdian Christians known in China from inscriptions and texts were An Yena, a Christian from An country (Bukhara). Mi Jifen a Christian from Mi country (Maymurgh), Kang Zhitong, a Sogdian Christian cleric from Kang country (Samarkand), Mi Xuanqing a Sogdian Christian cleric from Mi country (Maymurgh), Mi Xuanying, a Sogdian Christian cleric from Mi country (Maymurgh), An Qingsu, a Sogdian Christian monk from An country (Bukhara).[201][202][203]

When visiting Yuan-era Zhenjiang, Jiangsu, China during the late 13th century, the Venetian explorer and merchant Marco Polo noted that a large number of Christian churches had been built there. His claim is confirmed by a Chinese text of the 14th century explaining how a Sogdian named Mar-Sargis from Samarkand founded six Nestorian Christian churches there, in addition to one in Hangzhou during the second half of the 13th century.[204] Nestorian Christianity had existed in China earlier during the Tang dynasty when a Persian monk named Alopen came to Chang'an in 653 to proselytize, as described in a dual Chinese and Syriac language inscription from Chang'an (modern Xi'an), dated to the year 781.[205] Within the Syriac inscription is a list of priests and monks, one of whom is named Gabriel, the archdeacon of "Xumdan" and "Sarag", the Sogdian names for the Chinese capital cities Chang'an and Luoyang, respectively.[206] In regards to textual material, the earliest Christian gospel texts translated into Sogdian coincide with the reign of the Sasanian Persian monarch Yazdegerd II (r. 438–457), and were translated from the Peshitta, the standard version of the Bible in Syriac Christianity.[207]

Remove ads

Slave trade

Summarize

Perspective

Slavery existed in China since ancient times, although during the Han dynasty the proportion of slaves to the overall population was roughly 1%,[208] far lower than the estimate for the contemporary Greco-Roman world (estimated at 15% of the entire population).[209][210] During the Tang period, slaves were not allowed to marry a commoner's daughter, were not allowed to have sexual relations with any female member of their master's family, and although fornication with female slaves was forbidden in the Tang code of law, it was widely practiced.[211] Manumission was also permitted when a slave woman gave birth to her master's son, which allowed for her elevation to the legal status of a commoner, yet she could only live as a concubine and not as the wife of her former master.[212]

Sogdian and Chinese merchants regularly traded in slaves in and around Turpan during the Tang dynasty. Turpan under Tang dynasty rule was a center of major commercial activity between Chinese and Sogdian merchants. There were many inns in Turpan. Some provided Sogdian sex workers with an opportunity to service the Silk Road merchants, since the official histories report that there were markets in women at Kucha and Khotan.[214] The Sogdian-language contract buried at the Astana graveyard demonstrates that at least one Chinese man bought a Sogdian girl in 639 AD. One of the archaeologists who excavated the Astana site, Wu Zhen, contends that, although many households along the Silk Road bought individual slaves, as demonstrated in the earlier documents from Niya, the Turpan documents point to a massive escalation in the volume of the slave trade.[215] In 639 a female Sogdian slave was sold to a Chinese man, as recorded in an Astana cemetery legal document written in Sogdian.[216] Khotan and Kucha were places where women were commonly sold, with ample evidence of the slave trade in Turfan thanks to contemporary textual sources that have survived.[217][218] In Tang poetry Sogdian girls also frequently appear as serving maids in the taverns and inns of the capital Chang'an.[219]

Sogdian slave girls and their Chinese male owners made up the majority of Sogdian female-Chinese male pairings, while free Sogdian women were the most common spouse of Sogdian men. A smaller number of Chinese women were paired with elite Sogdian men. Sogdian man-and-woman pairings made up eighteen out of twenty-one marriages according to existing documents.[218][220]

A document dated 731 AD reveals that precisely forty bolts of silk were paid to a certain Mi Lushan, a slave dealing Sogdian, by a Chinese man named Tang Rong (唐榮) of Chang'an, for the purchase of an eleven-year-old girl. A person from Xizhou, a Tokharistani (i.e. Bactrian), and three Sogdians verified the sale of the girl.[218][221]

Central Asians like Sogdians were called "Hu" (胡) by the Chinese during the Tang dynasty. Central Asian "Hu" women were stereotyped as barmaids or dancers by Han in China. Han Chinese men engaged in mostly extra-marital sexual relationships with them as the "Hu" women in China mostly occupied positions where sexual services were sold to patrons like singers, maids, slaves and prostitutes.[222][223][224][225][226][227] Southern Baiyue girls were exoticized in poems.[228] Han men did not want to legally marry them unless they had no choice such as if they were on the frontier or in exile since the Han men would be socially disadvantaged and have to marry non-Han.[229][230][231] The task of taking care of herd animals like sheep and cattle was given to "Hu" slaves in China.[232]

Remove ads

Modern historiography

Summarize

Perspective

In 1916, the French Sinologist and historian Paul Pelliot used Tang Chinese manuscripts excavated from Dunhuang, Gansu to identify an ancient Sogdian colony south of Lop Nur in Xinjiang (Northwest China), which he argued was the base for the spread of Buddhism and Nestorian Christianity in China.[233] In 1926, Japanese scholar Kuwabara compiled evidence for Sogdians in Chinese historical sources, and by 1933, Chinese historian Xiang Da published his Tang Chang'an and Central Asian Culture, detailing the Sogdian influence on Chinese social religious life in the Tang-era Chinese capital city.[233]

The Canadian Sinologist Edwin G. Pulleyblank published an article in 1952, demonstrating the presence of a Sogdian colony founded in Six Hu Prefectures of the Ordos Loop during the Chinese Tang period, composed of Sogdians and Turkic peoples who migrated from the Mongolian steppe.[233] The Japanese historian Ikeda on wrote an article in 1965, outlining the history of the Sogdians inhabiting Dunhuang from the beginning of the 7th century, analyzing lists of their Sinicized names and the role of Zoroastrianism and Buddhism in their religious life.[234] Yoshida Yutaka and Kageyama Etsuko, Japanese ethnographers and linguists of the Sogdian language, were able to reconstruct Sogdian names from forty-five different Chinese transliterations, noting that these were common in Turfan whereas Sogdians living closer to the center of Chinese civilization for generations adopted traditional Chinese names.[169]

Remove ads

Notable people

- Amoghavajra, prolific translator and one of the most politically powerful Buddhist monks of Chinese history, of Sogdian descent through his mother[235][236]

- An Lushan (安祿山),[139] a military leader of Sogdian (from his father's side) and Tūjué origin during the Tang dynasty in China; he rose to prominence by fighting (and losing) frontier wars between 741 and 755. Later, he precipitated the catastrophic An Lushan Rebellion, which lasted from 755 to 763 and led to the decline of the Tang dynasty

- An Qingxu (安慶緒), son of An Lushan

- An Chonghui (安重誨), a minister of China's Later Tang

- An Congjin (安從進), a general of Later Tang and China's Later Jin (Five Dynasties)

- An Chongrong (安重榮), a general of China's Later Jin (Five Dynasties)

- Apama,[38] daughter of Spitamenes (see below) and wife of Seleucus I Nicator, founder of the Seleucid Empire

- Azanes,[20] son of Artaios, who led a contingent of Sogdian troops in the Persian army of Xerxes I during the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC

- Divashtich,[237] 8th-century ruler of Panjakent

- Fazang,[238] Buddhist monk and influent philosopher of the 7th century, considered the founder of the Huayan school

- Gurak,[71] 8th-century ruler of Samarkand

- Kang Senghui (康僧會),[239] Buddhist monk of the 3rd century who lived in Jiaozhi (modern-day Vietnam) during the Three Kingdoms period

- Kang Jing (康景)? – a possible Sogdian who worked at the Ming dynasty Mansion of the Prince of Qin (明朝藩王列表 (秦王系)) as a servant[240][241]

- Khaydhar ibn Kawus al-Afshin,[242] a general of the Abbasid caliphate and a vassal of the Abbasids as the prince of Osrushana during the 9th century

- Kaydar Nasr ibn 'Abdallah,[243] Abbasid governor of Egypt during the 9th century

- Li Baoyu (李抱玉),[139] formerly known as An Chongzhang (安重璋) and ennobled as Duke Zhaowu of Liang (涼昭武公), a general of the Chinese Tang dynasty who fought against the rebellion of An Lushan and the Tibetan Empire

- Mi Fu (米芾),[244] painter, poet, and calligrapher of the Song dynasty

- Malik ibn Kaydar,[245] a 9th-century general of the Abbasid caliphate

- Muzaffar ibn Kaydar, son of Kaydar Nasr ibn 'Abdallah (see above), and yet another Abbasid governor of Egypt during the 9th century

- Oxyartes,[30][31][32] Sogdian warlord from Bactria, follower of Bessus, and father of Roxana, the wife of Alexander the Great

- Roxana,[30][31][32][246] the primary wife of Alexander the Great during the 4th century BC

- Shi Jingtang (石敬瑭),[247] Emperor of China, temple name Gaozu (高祖)

- Spitamenes,[35] a Sogdian warlord who led an uprising against Alexander the Great in the late 4th century BC

- Tarkhun,[71] 8th-century ruler of Samarkand

- Abu'l-Saj Devdad, emir and official of the Abbasid caliphate and ancestor of the Sajid dynasty[248]

- Muhammad al-Bukhari, Hadith composer and Islamic scholar, writer of Salih Al-Bukhari.[249]

Remove ads

Diaspora areas

- A community of merchant Sogdians resided in Northern Qi era Ye.[250]

- A community of Sogdians existed in Jicheng (Beijing) since at least the time of the Tang dynasty. They were targeted for slaughter by the Tang government during the An Lushan rebellion.[251][252]

- Sogdians in Yizhou (Sichuan)

- Turkic Khaganate era Inner Mongolia.[253]

See also

- Ancient Iranian peoples

- Buddhism in Afghanistan

- Buddhism in Khotan

- Étienne de La Vaissière

- History of Central Asia

- Huteng

- Iranian languages

- Kangju

- List of ancient Iranian peoples

- List of Sodgian States

- Margiana

- Philip (satrap)

- Poykent

- Sogdian Daēnās

- Sughd Province

- Tajiks

- Tomb of Wirkak

- Tomb of Yu Hong

- Tocharians

- Yaghnobi people

- Yagnob Valley

- Yazid ibn al-Muhallab

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads