Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Japanese conjugation

Overview of how Japanese verbs conjugate From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

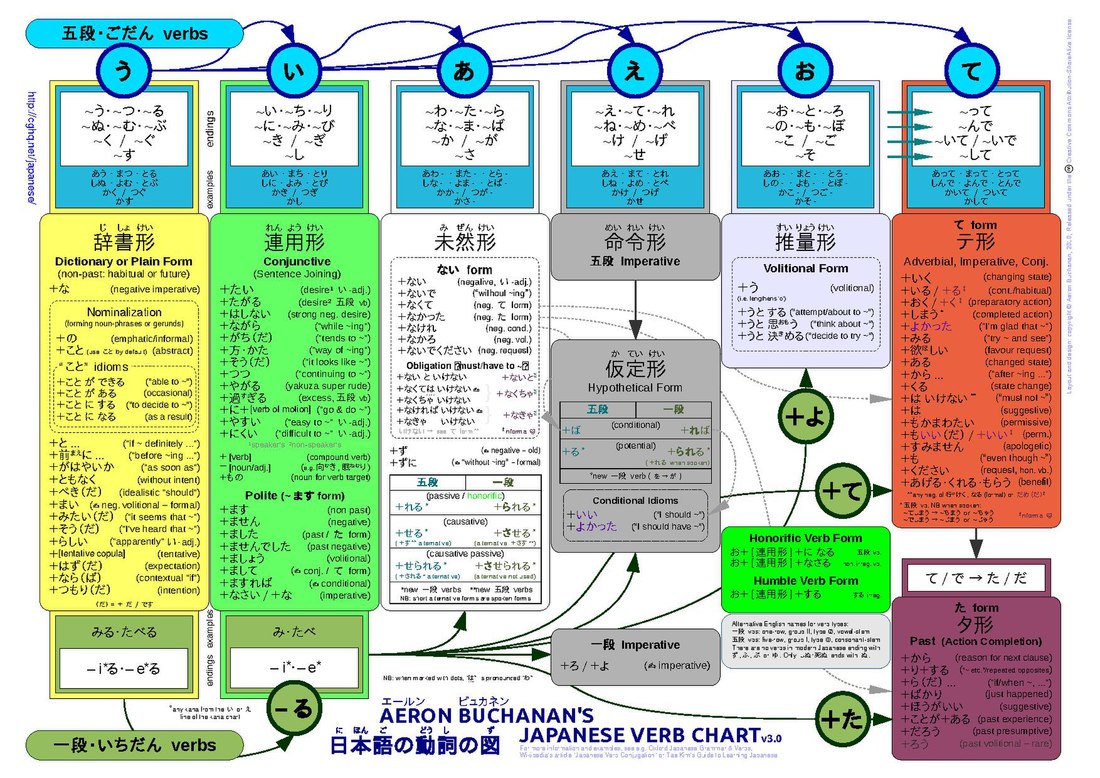

Japanese conjugation, like the conjugation of verbs of many other languages, allows verbs to be morphologically modified to change their meaning or grammatical function. In Japanese, the beginning of a word (the stem) is preserved during conjugation, while the ending of the word is altered in some way to change the meaning (this is the inflectional suffix). Japanese verb conjugations are independent of person, number and gender (they do not depend on whether the subject is I, you, he, she, we, etc.); the conjugated forms can express meanings such as negation, present and past tense, volition, passive voice, causation, imperative and conditional mood, and ability. There are also special forms for conjunction with other verbs, and for combination with particles for additional meanings.

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (August 2025) |

Japanese verbs have agglutinating properties: some of the conjugated forms are themselves conjugable verbs (or i-adjectives), which can result in several suffixes being strung together in a single verb form to express a combination of meanings.

Remove ads

Verb groups

Summarize

Perspective

For Japanese verbs, the verb stem remains invariant among all conjugations. However, conjugation patterns vary according to a verb's category. For example, 知る (shiru) and 着る (kiru) belong to different verb categories (godan and ichidan, respectively) and therefore follow different conjugation patterns. As such, knowing a verb's category is essential for conjugating Japanese verbs.

Japanese verbs can be allocated into three categories:[1]

- Godan verbs (五段動詞, godan-dōshi; literally: "five‑row verbs"), also known as "pentagrade verbs"

- Ichidan verbs (一段動詞, ichidan-dōshi; literally: "one‑row verbs"), also known as "monograde verbs"

- Irregular verbs, most notably: する (suru, to do) and 来る (kuru, to come)

Verbs are conjugated from their "dictionary form", where the final kana is either removed or changed in some way.[1] From a technical standpoint, verbs usually require a specific conjugational stem (see § Verb bases, below) for any given inflection or suffix. With godan verbs, the conjugational stem can span all five columns of the gojūon kana table (hence, the classification as a pentagrade verb). Ichidan verbs are simpler to conjugate: the final kana, which is always る (ru), is simply removed or replaced with the appropriate inflectional suffix. This means ichidan verb stems, in themselves, are valid conjugational stems which always end with the same kana (hence, the classification as a monograde verb).

This distinction can be observed by comparing conjugations of the two verb types, within the context of the gojūon table.[2]

- * These forms are given here in hiragana for illustrative purposes; they would normally be written with kanji as 見ない, 見ます etc.

As can be seen above, the godan verb yomu (読む, to read) has a static verb stem, yo- (読〜), and a dynamic conjugational stem which changes depending on the purpose: yoma- (読ま〜; row 1), yomi- (読み〜; row 2), yomu (読む; row 3), yome- (読め〜; row 4) and yomo- (読も〜; row 5). Unlike godan verb stems, ichidan verb stems are also functional conjugational stems, with the final kana of the stem remaining static in all conjugations.

Remove ads

Verb bases

Summarize

Perspective

Conjugable words (verbs, i‑adjectives, and na‑adjectives) are traditionally considered to have six possible conjugational stems or bases (活用形, katsuyōkei; literally "conjugation forms") .[3] However, as a result of the language evolving,[4][5] historical sound shifts,[6][7] and the post‑WWII spelling reforms,[8] three additional sub‑bases have emerged for verbs (seen in the table below as the Potential, Tentative, and Euphonic bases). Meanwhile, verbs no longer differentiate between the conclusive form (終止形, shūshikei; used to terminate a predicate) and the attributive form (連体形, rentaikei; used to modify a noun or noun phrase) bases (these bases are only distinguished for na‑adjectives in the modern language, see Japanese adjectives).[9][10] Verb bases function as the necessary stem forms to which inflectional suffixes attach.

The "default" dictionary form, or lemma, of any conjugational morpheme, be it a verb, an adjective or an auxiliary, is its conclusive form, which is listed first in the table below. The verb group (godan, ichidan, or irregular) determines how to derive any given conjugation base for the verb. With godan verbs, the base is derived by shifting the final kana along the respective vowel row of the gojūon kana table. With ichidan verbs, the base is derived by removing or replacing the final ru (る) kana.[2]

The table below illustrates the various verb bases across the verb groups, with the patterns starting from the dictionary form.[11]

Of the nine verb bases, the shūshikei/rentaikei, meireikei, and ren'yōkei bases can be considered fully conjugated forms without needing to append inflectional suffixes. In particular, the shūshikei/rentaikei and meireikei bases do not conjugate with any inflectional suffixes. By contrast, a verb cannot be considered fully conjugated in its kateikei, mizenkei, ishikei, kanōkei, or onbinkei base alone; a compatible inflectional suffix is required for that verb construction to be grammatical.[33]

Certain inflectional suffixes, in themselves, take on the form of verbs or i‑adjectives. These suffixes can then be further conjugated by adopting one of the verb bases, followed by the attachment of the appropriate suffix. The agglutinative nature of Japanese verb conjugation can thus make the final form of a given verb conjugation quite long. For example, the word 食べさせられたくなかった (tabesaseraretakunakatta) is broken down into its component morphemes below:

Derivative verb bases

There are three modern verb base forms that are considered to be derived from older forms. These are the potential, volitional, and euphonic sub‑bases, as shown in the Verb base formation table above.

As with all languages, the Japanese language has evolved to fulfil the contemporary needs of communication. The potential form of verbs is one such example. In Old Japanese and Early Middle Japanese, potential was expressed with the verb ending ゆ (yu), which was also used to express the passive voice ("to be done") and the spontaneous voice ("something happens on its own"). This evolved into the modern passive ending (ら)れる (-(ra)reru), which can similarly express potential and spontaneous senses. As usage patterns changed over time, different kinds of potential constructions emerged, such as the grammatical pattern of the rentaikei base + -koto ga dekiru (〜ことができる), and also via the kanōkei base.[4] The historical development of the kanōkei base is disputed, however the consensus is that it stemmed from a shift wherein transitive verbs developed an intransitive sense similar to the spontaneous, passive, and potential, and these intransitive forms conjugated in the 下二段活用 (shimo nidan katsuyō, lower bigrade conjugation pattern) of the Classical Japanese of the time.[5] The lower bigrade conjugation pattern evolved into the modern ichidan pattern in modern Japanese, and these stems for godan verbs have the same form as the hypothetical stems in the table above.

The mizenkei base that ends with -a was also used to express the volitional mood for yodan verbs (四段動詞, yodan-dōshi; "Class‑4 verbs") in Old Japanese and Middle Japanese,[disambiguation needed] in combination with volitional suffix む (-mu). Sound changes caused the resulting -amu ending to change: /-amu/ → /-ãu/ → /-au/ (like English "ow") → /-ɔː/ (like English "aw") → /-oː/. The post‑WWII spelling reforms updated spellings to reflect this and other sound changes, resulting in the addition of the ishikei or volitional base, ending with -o, for the volitional mood of yodan verbs. This also resulted in a reclassification of "yodan verbs" to "godan verbs" (五段動詞, godan-dōshi; "Class‑5 verbs").[8][34]

The ren'yōkei base also underwent various euphonic changes specific to the perfective and conjunctive (te) forms for certain verb stems,[35][6][7] giving rise to the onbinkei or euphonic base.[36] In the onbinkei base, the inflectional suffixes for godan verbs vary according to the last kana of the verb's ren'yōkei base.[2]

The bases of suru

Unlike most verbs, suru and its derived compounds exhibit strong irregularity in their verb bases. In some cases, some variants are preferred over the others, and such preferences vary among speakers. Roughly speaking, there are three major groups that behave similarly:[37]

- Group A: Suru itself and compounds of it and free nouns (which are usually, but not always, spelt with two more kanji if Sino-Japanese): jikkō suru (実行する; 'practise'), toku suru (得する; 'gain'), son suru (損する; 'lose'), bikkuri suru (吃驚する; 'be startled'), janpu suru (ジャンプする; 'jump'), etc.

- Group B: Compounds with bound Sino-Japanese morphemes that behave more like godan verbs. These often have full-fledged, interchangeable godan derivatives: aisu(ru) (愛す(る); 'love'), zokusu(ru) (属す(る); 'belong'), tassu(ru) (達す(る); 'reach'), etc.

- Such a form as aisenu (愛せぬ) is supposed to be the classical Japanese equivalent to aisanai (愛さない). Compare the following translations of 1 John 3:14 ("[...] Anyone who does not love remains in death."[38]):

- However, aisenu ("not love") as the negative of aisu(ru) ("love") would likely be confused with aisenu ("cannot love") as the negative of the potential aiseru ("can love") in modern Japanese. It is clear that aisenu is not the same as aisanu where they both occur in close proximity: Wa ga ko o aisanu mono wa arimasen. Wa ga ko sae aisenu mono ga, dō shite goshukun o aisemashō. (わが子を愛さぬ者はありません。わが子さえ愛せぬ者が、どうしてご主君を愛せましょう。; transl. No man does not love his own son. If he is not capable of loving even his own son, in what way could he ever love his lord?).[41]

- There is great variety among Group-B verbs as to whether to choose between the godan-negative -san(u)/-zu and the classical-negative -sen(u)/-zu, and there are indeed cases where only contexts can clarify whether -sen(u)/-zu are truly classical-negative, or actually godan-negative-potential. In general, it seems that if the Sino-Japanese stem contains a moraic obstruent as in kussuru (屈する; くっする, /kɯQsɯɾɯ/), a moraic nasal as in hansuru (反する; はんする, /haNsuru/), or lengthening mora as in kyōsuru (供する; きょうする, /kjoRsɯɾɯ/), the godan options are less preferable with all auxiliaries (including the negative -n(u)/-zu), though not impossible. Thus, such forms as kussenu/kussezu (屈せぬ・屈せず; 'not bend') are more likely to be classical-negative, while such forms as aisenu/aisezu (愛せぬ・愛せず; 'cannot love') are more likely to be godan-negative-potential; and while both kussanu/kussazu (屈さぬ・屈さず; 'not bend') and aisanu/aisazu (愛さぬ・愛さず; 'not love') are unambiguously godan-negative, the former are not as likely as the latter.[37]

- Group C: Compounds with bound Sino-Japanese morphmes that behave more like upper (i-stemmed) ichidan verbs. These often have full-fledged, interchangeable upper ichidan derivatives: ronzuru → ronjiru (論ずる→論じる; 'discuss'), ōzuru → ōjiru (応ずる→応じる; 'respond'), omonzuru → omonjiru (重んずる→重んじる; 'appreciate'), sassuru → sasshiru (察する→察しる; 'surmise'), etc.

- Group D: Compounds with bound Sino-Japanese morphemes that behave more like lower (e-stemmed) ichidan verbs. These may have full-fledged, interchangeable lower ichidan derivatives: shinzuru → shinzeru (進ずる→進ぜる; 'provide') and misuru → miseru (魅する→魅せる; 'enchant').

Across the following forms of suru within standard Japanese, an eastern dialect, while there is a dominance of the eastern vowel i as in shinai,[42] shiyō[43] and shiro,[44] the once prestigious western vowel e, as in sen(u) and seyo, still has currency especially in formal or literary Japanese. Such variants as senai and sanai (both of shinai); shin(u) (of sen(u)); shō (← seu), seyō and sō (all of shiyō); sero (of shiro); and shiyo, sē and sei (all of seyo), remain dialectal or obsolete.[45][46][47]

Remove ads

Copulae: de aru, da, de arimasu and desu

Summarize

Perspective

The copula or "to be" verb in Japanese is a special case. This comes in two basic forms, だ (da) in the plain form and です (desu) in the polite form. These are generally used to predicate sentences, equate one thing with another (i.e. "A is B."), or express a self‑directed thought (e.g. a sudden emotion or realization).[49]

Copulae: Conjugation table

The copulae of Japanese demonstrate suppletion, in that they combined different forms from different words into one word. The original copulae were all based on the verb ari (あり; 'to exist'), which evolved into the modern aru (ある). It needed to be preceded by one of the three particles, ni, ni te → de[50][51] and to, which yielded three variants, ni ari/ni aru → nari/naru,[52] de ari/de aru → da[53] and to ari/to aru → tari/taru, the last of which fell out of use, but did phonetically coincide with te ari/te aru → tari/taru,[54] which in turn evolved into the modern past auxiliary ta.[55] It also combined with adjectival roots to expand their conjugation, for example akaku arō → akakarō (赤かろう), akaku atta → akakatta (赤かった), etc.

- The original conclusive de ari, was replaced by the attributive de aru, which evolved into the informal conclusive da, and the formal conclusive de aru. In terms of formality and politeness:

- Da is informal and impolite. Depending on specifically what precedes it, da can be perceived as abrupt or too masculine, and therefore is customarily omitted in some cases.[56]

- De aru is formal and nonpolite (with no inherent assumption of politeness).

- Desu is nonformal (with no inherent assumption of formality) and polite.

- De arimasu is formal and polite.

- Da/datta/darō are the colloquial contractions of de aru/de atta/de arō in eastern dialects (including Tokyo Japanese). Their western equivalents include ja/jatta/jarō and ya/yatta/yarō.[57] Ja/jatta/jarō, along with other western features (-n(u), -nanda, u-onbin, etc), are occasionally used in faux-archaic speech[58] rather dialectal speech; for example, the character Gandalf, an ancient wizard from The Lord of the Rings, is made to speak with a few selectively chosen western features,[i] while still retaining some eastern features,[j] in the Japanese translations (see relevant quotations in the footnotes).

- Gozaru (御座る; contracted from goza aru) is the honorific version of aru, and goza(r)imasu is the honorific version of arimasu. Gozaru has most of the forms that aru does ((de (wa)) gozaru, (de (wa)) gozaranu, (de (wa)) gozareba, etc), although it additionally undergoes a minor sound change in the polite conclusive/attributive gozarimasu → gozaimasu and the imperative gozare → gozai. Gozaimasu is authentically used in modern Japanese, while gozaru, gozarimasu(ru) and gozaimasuru are used for effect, such as in theatrical or humorous lines.[59]

- The current attributive form of de (wa) aru is still de (wa) aru. Da additionally takes naru → na (of said nari) as its attributive form[60] only in adjectival verbs,[61] as in kirei na hana (綺麗な花; 'pretty flower', lit. 'a flower, which is pretty'), and after the auxiliaries sō (そう), yō (よう) and mitai (みたい), as in rikō sō na kao (利口そうな顔; 'smart-looking face', lit. 'a face, which appears smart') and kanojo no yō na hito (彼女のような人; 'someone like her', lit. 'a person, who is like her'); while the particle no is used after nouns, as in tomodachi no Yūko (友達の裕子; 'my friend Yūko', lit. 'Yūko, who is my friend') or bijin no onēsan (美人のお姉さん; 'my beautiful sister', lit. 'my sister, who is a beauty'). However, since no also expresses possession, this may cause ambiguity, as in isha no ojisan (医者のおじさん; lit. 'my uncle, who is a doctor; my doctor's uncle');[62] moreover, some nouns can function as either "adjectival verbs" or "nouns", and take either na or no, such as iroiro na mono/iroiro no mono (色々な物・色々の物; 'various things'). The old naru (of said nari) and taru (of said to ari/to aru → tari/taru) can still be used for literary effect, as in zetsudai naru gokitai (絶大なるご期待; 'the utmost anticipation'), Hokkaidō naru chihō (北海道なる地方; 'Hokkaido region'), isha taru hito (医者たる人; 'a person, who is known as a doctor'), kyōshi taru mono (教師たるもの; 'those who call themselves teachers'), or in such idiom as sei naru (聖なる; 'holy') or dōdō taru (堂々たる; 'splendid').[61] Incidentally, an ancient possessive na was fossilized in words like manako (眼; 'eyeball', lit. 'eye's child'), minato (港; 'harbor', lit. 'water's door'), tanagokoro (掌; 'palm', lit. 'hand's heart'), etc.[63] There is also a niche distinction between Kōbe no hito (神戸の人; 'person from Kobe', lit. 'Kobe's person') and Kōbe na hito (神戸な人; 'person seeming like they could be from Kobe', lit. 'Kobe-ish person').[64] Na is also used before the nominalizer no, as in sobo wa hyakusai na no da (祖母は100歳なのだ; lit. 'it's a fact that my grandma is 100 years old').

- The three conjunctive forms (two of which are particles) combine with different words,[65][66][21] each with its own parallel:

- ni + naru → ni naru ("become"), parallel with akaku + naru → akaku naru ("become red")

- de + aru → de aru ("be"), parallel with akaku + aru → akaku aru ("be red") and nomi + suru → nomi suru ("drink")

- de + nai → de nai ("not be"), parallel with akaku + nai → akaku nai ("not be red") and nomi + shinai → nomi shinai ("not drink")

- de ari + -masu → de arimasu ("be"),[k] parallel with nomi + -masu → nomimasu ("drink")

- The above formations allow "splitting",[67] or adding particles like wa or mo between the conjunctive forms and the following verbs, which would be impossible with da ("be"), akai ("be red") and nomu ("drink") alone:

- da ("be"), parallel with akai ("be red") and nomu ("drink")

- ni mo naru ("become ..., too"), parallel with akaku mo naru ("become red, too")

- de wa aru ("be ..., indeed"), parallel with akaku wa aru ("be red, indeed") and nomi wa suru ("drink, indeed")

- de wa nai ("not be ..., indeed"), parallel with akaku wa nai ("not be red, indeed") and nomi wa shinai ("not drink, indeed")

- The particles wa and mo are often added, especially to the negatives, although not required in principle.[50][68] Wa puts focus on what goes after it, while mo puts focus what goes before it.[69] In the following sentences, the focused information is underlined for the Japanese originals and the literal English translations; for the non-literal English translations, all-caps type emulates how an English speaker would emphasize the focused information.

- Kono hen ga shizuka da. (この辺が静かだ。; lit. 'This area[, not any other area,] is quiet.', transl. THIS area is quiet.)

- Kono hen mo shizuka da. (この辺も静かだ。; lit. 'This area, too, [along with at least another area,] is quiet.', transl. THIS area's also quiet.)

- Kono hen wa shizuka da. (この辺は静かだ。; lit. 'This area? It's quiet.', transl. This area's QUIET.)

- Kono hen wa shizuka de wa aru ga, fuben da. (この辺は静かではあるが、不便だ。; lit. 'This area? Being quiet? It is indeed, but it's inconvenient.', transl. This area IS quiet, but it's inconvenient)

- Sometimes de and aru can be split quite widely:[70]

- Ikuji nashi! Soshite mattaku sono tōri de watashi wa atta no da. (意氣地なし! そして全くその通りで私はあったのだ。[71]; transl. A wuss! I WAS exactly just that.)

- While de nai/arimasen are sometimes used in formal contexts, in ordinary speech ja nai/ja arimasen are used instead. In this case, even though ja is etymologically a colloquially reduced version of de wa,[10] ja nai/arimasen are, functionally, colloquial versions of either de nai/arimasen, which focus on what comes before them, or de wa nai/arimasen which focus on nai/arimasen. Some speakers distinguish the short ja (じゃ) for de and the long jā (じゃあ) for de wa.[72]

- Marukusu to Renin no shinja de nai desu ka /~ ja arimasen ka (マルクスとレニンの信者でないですか・~じゃありませんか; lit. 'Are they not believers in Marx and Lenin?', transl. Aren't they BELIEVERS in Marx and Lenin?)

- Marukusu to Renin no shinja de wa nai desu ka /~ ja(a) arimasen ka (マルクスとレニンの信者ではないですか・~じゃ(あ)ありませんか; lit. 'Believers in Marx and Lenin? Is that not what they are?', transl. Are they NOT believers in Marx and Lenin?)

- While de (wa) arimasen and de (wa) arimasen deshita are often recommended, de (wa) nai desu and de (wa) nakatta desu are acceptable colloquial alternatives.[73] For the idiosyncratic de (wa) aranai and de (wa) arimashinai, see #Negative: Conjugation table.

- De (wa) areba is the regular way of forming conditionals (仮定形, kateikei) in modern Japanese. Naraba (of said nari) is kept as the conditional of da, and along with taraba (of said te ari/te aru → tari/taru → ta), retains the old way of forming conditionals. See #Conditional: Conjugation table or more.

- Desu, a copula of uncertain origin, takes its missing forms from de (wa) aru and de (wa) arimasu, the latter of which is conceivably the ancestor of desu.[74]

- Although なら(ば) (nara(ba)), だろう (darō) and でしょう (deshō) were originally conjugations of だ (da) and です (desu), they are now also used as particles or auxiliaries and can attach directly to other verbs' conclusive/attributive forms, as in kaku nara(ba) (書くなら(ば); 'if one writes'), kaku darō/deshō (書くだろう・でしょう; 'one will probably write'). Unlike da which is inherently blunt and only suitable for familiar speech, nara(ba) and darō are suitable for writing.[75] Desu (or de arimasu or de gozaimasu), deshita and deshō can add politeness the negative auxiliaries -n(u) and -nai, as well as adjectives:[76]

- Arimasen/gozaimasen / nai desu/de arimasu/de gozaimasu / naku arimasu / nō gozaimasu ("be not")

- Arimasen/gozaimasen deshō / nai deshō/de arimashō/de gozaimashō / naku arimashō / nō gozaimashō ("be probably not")

- Arimasen/gozaimasen deshita / nakatta desu/de arimasu/de gozaimasu / naku arimashita / nō gozaimashita ("were not")

- Arimasen/gozaimasen deshita deshō / nakatta deshō/de arimasu/de gozaimasu / naku arimashita deshō / nō gozaimashita deshō ("were probably not")

- Akai desu/de arimasu/de gozaimasu / akaku arimasu / akō gozaimasu ("be red")

- Akai deshō/de arimashō/de gozaimashō / akaku arimashō / akō gozaimashō ("be probably red")

- Akakatta desu/de arimasu/de gozaimasu / akaku arimashita / akō gozaimashita ("were red")

- Akakatta deshō/de arimasu/de gozaimasu / akaku arimashita deshō / akō gozaimashita deshō ("were probably red")

- As shown above, desu does not have its own negative form, and instead borrows de (wa) arimasen from de (wa) arimasu. However, the auxiliary -n in de (wa) arimasen in turn does not have its own past and conjectural form, therefore deshita and deshō have to be added. The past conjectural -tarō is infrequent, thus instead of deshitarō, deshita deshō is preferred.[77]

Copulae: Grammatical compatibility

Derived from aru and arimasu, the copulae can have all the forms that these verbs are capable of having. Certain affirmative conclusive and attributive forms have contracted, especially in speech, such as de aru → da/ja and de arimasu → desu; the negative forms remain uncontracted, meaning there is no such form as *daran or *desen. Furthermore, the perfective forms, だった (datta) and でした (deshita), are compatible with the ~tara conditional.[197]

Remove ads

Imperfective

Summarize

Perspective

The imperfective form (also known as the "non‑past", "plain form", "short form", "dictionary form" and the "attributive form") is broadly equivalent to the present and future tenses of English. In Japanese, the imperfective form is used as the headword or lemma. It is used to express actions that are assumed to continue into the future, habits or future intentions.[198]

The imperfective form cannot be used to make a progressive continuous statement, such as in the English sentence "I am shopping". To do so, the verb must first be conjugated into its te form and attached to the いる (iru) auxiliary verb .

Imperfective: Conjugation table

Certain ‑suru or ‑zuru verbs and their godan and ichidan equivalents are interchangeable (or at least sensitive to specifically what follows them) and even used in the same text, although it has been claimed that, at least for the conclusive/attributive form, the more classical/literary (文語, bungo)/western ‑zuru variants are more "formal" and "basically a written form",[199] compared to the more modern/colloquial (口語, kōgo)/eastern ‑jiru variants.[200] The ‑su variants are highly inconsistent across verbs, and even for highly "godan‑ized" verbs like aisuru (愛する), whose other forms are predominantly godan, the conclusive/attributive aisuru and conditional aisureba in particular are still preferred to the fully godan variants aisu and aiseba.[37] In some cases it is not clear whether aisu is godan or actually pseudo-classical, for example in aisu beki (愛すべき) where all ‑suru verbs can optionally lose the ru. In classical or pseudo-classical literature, aisu is more likely to be conclusive and aisuru is more likely to be attributive or nominalized.

The politeness auxiliary ‑masuru is characterized as "pseudo-literary"[201] or faux archaic.[202] It was used in parliamentary speech during the 20th century, but usage drastically declined into the 21st century.[203] Some examples include Wakayama ni orimasuru haha (和歌山に居りまする母; 'my mother who is in Wakayama'), Taku e de mo maitte iru yō ni itasō ka to zonjimasuru no de gozaimasu (宅へでも参っているように痛そうかと存じまするのでございます; 'I am wondering whether I should decide to come and stay perhaps at your house'), Sore ni gisei no tame o omotte mimasuru to, geshuku ni okimasu no wa ikaga de gozaimashō (それに犠牲の為を思って見ますると、下宿に置きますのはいかがでございましょう; 'And thinking of the victims' welfare, how about putting them in a boarding house?'). The conjugational similarity between ‑masu and suru suggests an etymological link.[204]

The sound sequence /Vi/, with /V/ being a vowel, is often colloquially and masculinely fused into a long vowel. Since all adjectival conclusive/attributive forms have this sound sequence, they are liable to such fusion. Most adjectives of this kind remain distinctly masculine, and their phonetic spellings are found in written dialog for masculine characters in fiction, such as nai → nē (ねえ・ねー; 'nonexistent'), urusai → urusē → ussē (うるせえ・うるせー・うっせえ・うっせー; 'noisy; pesky'), hayai → ha(y)ē (はええ・はえー; 'quick'), sugoi → sugē (すげえ・すげー; 'superb'), tsuyoi → tsu(y)ē (つええ・つえー; 'strong'), warui → warī (わりい・わりー; 'bad'), yasui → yashī (やしい・やしー; 'easy; cheap'), mazui → majī (まじい・まじー; 'unpalatable'), atsui → achī (あちい・あちー; 'thick; hot'), kayui → kaī (かいい・かいー; 'itchy'), etc. Non-masculine examples include yoi → (y)ē → ī (いい・いー; 'good'),[205] and kawayui → kawaī (かわいい・かわいー; 'adorable'). See Japanese phonology § Vowel fusion for further citations.

The classical conclusives nashi and yoshi in particular are now more of cliches rather than catch-all representatives of adjectives in general. Nashi is often used as a nominal suffix meaning "without", "‑less" or "‑free", as in satō nashi no jōzai (砂糖なしの錠剤; 'sugar-free tablet'). Yoshi is often used as an interjection meaning "Good!" or "Alright!". The classical onaji has evolved into an adjectival noun (onaji da/de aru/desu, onaji (na), etc), and despite being originally conclusive, it is now prevalently attributive. Other examples of classical conclusives for cliched, proverbial and elevated uses include Tenki wa yoshi, kaze wa nashi, buratsuku no ni motte koi no hi da (天気はよし、風はなし、ぶらつくのに持ってこいの日だ; transl. The weather's nice, there's no wind, it's the perfect day to stroll), Genkin fuyō jidai, chikashi de aru (現金不要時代、まさに近しである; transl. The cashless era is nigh), Eyasuki mono wa ushinaiyasushi (得やすきものは失いやすし; transl. Easy come, easy go), Kyū kābu Jiko ōshi (急カーブ 事故多し; transl. Sudden curve: Many accidents),[206] etc.

The classical attributive ending ‑ki, the ancestor of the modern attributive/conclusive ending ‑i, is still used in elevated cliches and titles for books and fictional characters, such as jinkaku naki shadan (人格無き社団; 'unincorporated association'),[207] Osorenaki Tansasha, Akiri (恐れなき探査者、アキリ; 'Akiri, Fearless Voyager'),[208] furuki yoki jidai (古き良き時代; 'the good old days'),[207] yoki Samariya‑bito/‑jin / hitsujikai (善きサマリヤ人・羊飼い; 'the good Samaritan / shepherd'), Utsukushiku Aoki Donau (美しく青きドナウ; 'The Beautiful Blue Danube'), Aoki Me no Otome (青き眼の乙女; transl. Maiden with Eyes of Blue),[209] Akaki Ryū (赤き竜; transl. Crimson Dragon),[210] Atarashiki Mura (新しき村; lit. 'New Village'), Imawashiki Tsurīfōku (忌まわしきツリーフォーク; 'Ambominable Treefolk'),[211] etc.

The attributive ending ‑karu, a fusion of the infinitive ending ‑ku and the verb aru, is uncommon in modern Tokyo Japanese. It has been found in such constructions with ‑beki as tanoshikaru beki (楽しかるべき; transl. that ought/is supposed to be joyful; that is otherwise happy).[212] In Kyushu, ‑karu was reduced further to ‑ka,[213] and yoka is used instead of either yoi or yoshi.[214][s]

The classical adjectival extenders beshi, gotoshi and maji are still used in elevated language. Their attributives retain the ‑ki ending as in beki, gotoki, majiki, although the ‑i ending as in bei, majii has historically and dialectally occurred.[215][216] For beshi in particular, its attributive beki can be used conclusively in the phrase beki da/de aru/desu. For more examples, see #Imperfective: Grammatical compatibility below.

Imperfective: Grammatical compatibility

The imperfective conclusive/attributive form can be followed by various extenders.[250]

Of these extenders, beshi, beki, beku, etc are capable of reviving classical conclusive forms such as the irregular su (す; 'do') and ku (来; 'come'), and the nidan (二段) u (得; 'get'), tabu (食ぶ; 'eat'), kazō (数ふ; 'count'), otsu (落つ; 'fall'), etc. These can be substituted with the modern irregular suru (する) and kuru (来る), and the ichidan eru (得る), taberu (食べる), kazoeru (数える), ochiru (落ちる), etc. With the classical irregular conclusive ari (あり; 'exist') and its derivatives, however, the attributive is used instead, as in aru beshi (あるべし; 'ought to be'), yokaru beshi (良かるべし; 'ought to be good'), etc rather than *ari beshi, *yokari beshi, etc, and such exceptions coincide with the modern godan conclusive aru of the same verbs.[251][252][205]

Remove ads

Negative

Passive

Potential

Causative

Volitional

Conjunctive

te form

Perfective

Imperative

Summarize

Perspective

The imperative form functions as firm instructions do in English. It is used to give orders to subordinates (such as within military ranks, or towards pet animals) and to give direct instructions within intimate relationships (for example, within family or close friends). When directed towards a collective rather than an individual, the imperative form is used for mandatory action or motivational speech.[256] The imperative form is also used in reported speech.

However, the imperative form is perceived as confrontational or aggressive when used for commands; instead, it is more common to use the te form (with or without the please do (〜下さい, ‑kudasai) suffix), or the conjunctive form's polite imperative suffix, ‑nasai (〜なさい).[256]

Imperative: Conjugation table

The honorific godan verbs are originally おっしゃれ (osshare), 下され (kudasare), 為され (nasare), 御座れ (gozare), just like other godan/四段 (yodan) verbs, though *いらっしゃれ (irasshare) was not found. These forms are obsolescent and only used for special effect, such as in advertisements.[291] Historically, honorific verbs were 二段 (nidan) rather than godan/yodan, and western imperative forms like いらせられよ (iraserareyo; → irasshai), 仰せられよ (ōserareyo; → osshai), 下されよ・下されい (kudasareyo/kudasarei; → kudasai), 為されよ (nasareyo; → nasai) are attested. From these nidan verbs, apart from the godan offshoots, there still exist ichidan equivalents. Some rural eastern dialects still have 為さろ (nasaro).[292][293]

With non-godan verbs, there are two imperative forms, one ending in ‑ro (〜ろ) and one in ‑yo (〜よ). ‑Ro has been characterized as used for speech, while ‑yo as used for writing.[294] In actuality, this corresponds to a difference between modern Japanese (口語, kōgo; lit. 'oral language') based on the eastern Tokyo Japanese dialect,[aa] and Classical Japanese (文語, bungo; lit. 'literary language'), various literary stages of premodern Japanese based on western dialects.[296][297][298] Both ‑ro and ‑yo were interjectional particles in Old Japanese,[299][ab][300][301] and were sometimes optional, sometimes obligatory with non-godan verbs. ‑Yo became obligatory with non-godan verbs toward Early Middle Japanese, and its reduced variant ‑i arose during Late Middle Japanese.[302][ac] Historically and dialectally, mi-yo/mi-i/mi-ro/mi (見よ・見い・見ろ・見; 'look!'), oki-yo/oki-i/oki-ro/oki (起きよ・起きい・起きろ・起き; 'get up!'), ke-yo/ke-i/ke-ro/ke (蹴よ・蹴い・蹴ろ・蹴; 'kick!'),[ad] ake-yo/ake-i/ake-ro/ake (開けよ・開けい・開けろ・開け; 'open!') (all ichidan), se-yo/shi-yo/se-i/shi-i/se-ro/shi-ro/se/shi (せよ・しよ・せい・しい・せろ・しろ・せ

し; suru, 'do!') and ko-yo/ki-yo/ko-i/ki-i/ko-ro/ki-ro/ko/ki (来よ・来い・来ろ・来; kuru, 'come!') were all possible,[303][304][305] with ‑yo and ‑i being the western forms, and ‑ro being the eastern form.[306][307][308][309] The division between western ‑yo/‑i and eastern ‑ro still exists today.[310][311] According to a 1991 survey:

- ‑Ro dominates eastern dialects.[312][313][314]

- ‑Yo is found mostly in central Chūbu and eastern Kyushu.

- ‑I dominates western dialects in Honshu and Shikoku, and marginally in Shitamachi, Tokyo.[295]

- ‑Re, likely as a shortened ‑ro‑i,[295] is found in the northernmost dialects in Hokkaido and the southernmost ones in Kyushu.

- Shiro ("do!") dominates eastern dialects, while sē does western dialects. Seyo and shiyo concentrate in central Chūbu, while sero and sere do in western Kyushu.[44]

- There exist such fused forms as myo(o) (← miyo, "look!"), okyo(o) (← okiyo, "rise!"), akyo(o) (← akeyo, "open!") and sho(o) (← seyo, "do!") in Shizuoka Prefecture and some surrounding areas.

- Koi ("come!") occurs consistently across Japan, although kō has a strong presence in the east. There is a concentration of kē and ke in Kyushu. Koyo is rare in contemporary Japanese dialects,[315] despite being the standard form in classical Japanese. According to another account, koro occurs in an Akita dialect, while kiro is found in Ibaraki. Other variants include kiyo, kī, kui, keyo, etc.[301]

- In some dialects, okiro(o), akero(o), nero(o), koro(o), shiro(o) are actually volitional forms, not imperative forms.[316][317][318][319][320]

In modern Tokyo Japanese (eastern, specifically Yamanote Japanese), ‑yo largely displaced ‑ro in non-imperative contexts. ‑Yo can be optionally added to modern imperative forms with no historical ‑yo, as in kake yo (書けよ; 'write!'), miro yo (見ろよ), shiro yo (しろよ), koi yo (来いよ); ‑ro can no longer be used this way, although historically it used to occasionally be, as with yodan imperatives like oke ro (置けろ; 'put!') or yome ro (読めろ; 'read!').[301] Although ‑yo imperative forms already contain ‑yo and are primarily "written", it is not impossible for them to be followed by another colloquial ‑yo, as in Kura o akeyo yo (倉を開けよよ; 'Open the storehouse, would you?')[321] or Mō neyo yo (もう寝よよ; 'Just sleep already, would you?').[322] Apart from the difference between eastern and western dialects, there exists a register difference ‑yo and ‑ro within standard Japanese.[309] ‑Yo, as the more prestigious classical form of the former western capitals (Nara, Kyoto and Osaka), is still used in formal instructions, such as on test forms,[323] in academic questions,[324] on signage, in formal or polite quoted commands[295] or concessive clauses (spoken[325][326][327][328] or written[329][330][331]), etc. On the other hand, ‑ro, as the more colloquially common form, has a connotation of rudeness.[309][ae]

Despite originally having the same conjugation as suru,[332] the imperative form of ‑masu(ru) is not *‑mashiro. However, there used to be ‑masei, with ‑i being the western reduced form of ‑yo.[333] ‑Mase yo exists, though not mandatorily like seyo, but only as ‑mase optionally followed by ‑yo. ‑Mashi is a later variant, characteristic of Shitamachi.[201] It used to be common during the Meiji era, but now has a connotation of unrefined speech. ‑Mase and ‑mashi are meant to be used with honorific verbs, as in irasshaimase (いらっしゃいませ), nasaimase (為さいませ), asobashimase (遊ばしませ), meshiagarimase (召し上がりませ), etc, and not with ordinary verbs like *kakimase (書きませ) or *arukimase (歩きませ).[202]

Gozai and gozare are used as a more polite way to say "come!" instead of 来い (koi). They also occur in the concessive idiom nan de mo gozai/gozare (lit. 'be it anything', transl. anything goes; anything's good; anything imaginable),[207] which is synonymous with nan de mo koi.[334]

Are and de (wa) are have limited use in formal contexts, for example Kami mo shōran are (神も照覧あれ; 'may God be my witness'),[295] hikari are (光あれ; 'let there be light'), Ito takaki tokoro ni wa eikō, Kami ni are, chi ni wa heiwa, mikokoro ni kanau hito ni are. (いと高きところには栄光、神にあれ、地には平和、御心に適う人にあれ。; 'In the highest realm, glory be unto God, on earth, peace be unto those who earn his grace.'),[335] itsumo Kami ni shitagatte are. (いつも神に従ってあれ。; 'always be obedient to God.'),[336] shōjiki de are (正直であれ; 'be honest').[295] De (wa) are also has a concessive use, as in Riyū wa nan de are, bōryoku wa yoku nai yo. (理由は何であれ,暴力はよくないよ。; 'No matter the reason, violence is not good.'),[337] Nan no heya de are, mō koko ni tomete morau hoka wa nai (何の部屋であれ、もうここに泊めてもらうほかはない; 'Whatever the room may be, we have no choice but to stay here.').[338] This has been linked to a probable contraction from the identically sounding conditional base, de are, preceding the concessive particle ‑do, as in de aredo.[338] However, unambiguously imperative bases in ni seyo and ni shiro also have concessive uses, as in Sanka suru ni seyo, shinai ni seyo, toriaezu renraku o kudasai. (参加するにせよ,しないにせよ,とりあえず連絡を下さい。; 'Whether you partake or not, please get in touch soon.') and Soba ni shiro, udon ni shiro, menrui nara nan de mo ii n da. (そばにしろ,うどんにしろ,麺類なら何でもいいんだ。; 'Soba, udon, whatever, any kind of noodles will do.')[337]

Unlike are, adjectival imperative forms derived from fusions with it (‑ku are → ‑kare), seem to be used mostly for concession, as in ōkare sukunakare (多かれ少なかれ; 'be there more or less'), takakare yasukare (高かれ安かれ; 'be it expensive or cheap'), tsuyokare yowakare (強かれ弱かれ; 'be it strong or weak'), osokare hayakare (遅かれ早かれ; 'be it later or sooner'), yokare ashikare (良かれ悪しかれ; 'be it good or bad'),[339] tōkare chikakare (遠かれ近かれ; 'be it far or near'), etc and occasionally for elevated wishes, as in Yasukare (安かれ; transl. May you be at peace)[207][af] or Sachi ōkare (幸多かれ; transl. Best of luck to you).[341] The exceptional nakare ("let there not be") expresses elevated and/or motivational negative commands or wishes, as in Ogoru nakare! Jimintō (驕るなかれ!自民党; transl. Do not be prideful! O, Liberal Democratic Party), Taka ga benpi to yū nakare (高が便秘と言うなかれ; transl. Don't say it's just constipation), etc. The phrase koto nakare (事なかれ; lit. 'let there be no incident') is used in koto nakare shugi (事なかれ主義; 'principle of not rocking the boat').[207] Nakare behaves syntactically like the negative imperative particle na, which is similarly placed after an attributive/conclusive verb, thus ogoru na (驕るな; 'don't be prideful'), yū na (言うな; 'don't say'), etc.[342] Unfused ‑ku are forms have also been found, as in kiyoku are (清くあれ; 'be pure!').[343]

Conditional

Summarize

Perspective

The conditional form (also known as the "hypothetical form", "provisional form" and the "provisional conditional eba form") is broadly equivalent to the English conditionals "if..." or "when...". It describes a condition that provides a specific result, with emphasis on the condition.[399] The conditional form is used to describe hypothetical scenarios or general truths.[400]

Conditional: Conjugation table

The conditional form is created by using the kateikei base, followed by a conditional particle, usually the hypothetical/provisional ba (ば), and occasionally with the elevated concessive do (mo) (ど(も)).

The ‑eba ending can be colloquially reduced to ‑ya(a), where the consonant b is weakened to the point of complete omission, as in ieba → *iewa → iya(a) (言えば; 'provided that one says'), ikeba → *ikewa → ikya(a) (行けば; 'provided that one goes'), mireba → *mirewa → mirya(a) (見れば; 'provided that one looks'), etc. In cases like mateba → *matewa → matya(a) (待てば; 'provided that one waits'), hanaseba → *hanasewa → hanasya(a) (話せば; 'provided that one speaks'), etc, the consonants ty and sy may be used rather than ch and sh.[401] The adjectival ending ‑kereba → ‑kerya(a) in particular can be further reduced to ‑kya(a), as in akakereba → *akakerewa → akakerya(a) → akakya(a) (赤ければ; 'provided that one's red'). In western dialects where ‑n is used instead of ‑nai, there are ‑nkerya(a) and ‑nkya(a) (from ‑nkereba), and ‑nya (from ‑neba).[402] These colloquial reductions are analogous to how ‑te wa/‑de wa are reduced to ‑tya(a)/‑dya(a), ‑te aru/‑de aru/‑te yaru/‑de yaru to ‑ty(a)aru/‑dy(a)aru, de wa to dya(a) to ja(a), and de atte to dy(a)atte to j(a)atte, etc, although some of these reductions may be more dialectal than the others.[403]

The polite auxiliary -masu has two options, the provisional ‑masureba, and the morphologically hypothetical yet semantically provisional -maseba.[404] -Masureba has been said to be uncommon, while ‑maseba has been said to be nonstandard.[405]

Provisional vs hypothetical

In classical Japanese, there was a distinction between the provisional izenkei (已然形) base, which expresses a prerequisite condition ("provided that one is/does"), and the hypothetical mizenkei (未然形) base, which expresses a contingent condition ("if one happens to be/do"). Furthermore, when these constructions are used in perfect clauses, they express temporal conditions ("when/because one had been/done").[442] Modern Japanese replaced the classical hypothetical base with the classical perfect hypothetical (which is dubbed the conditional by Martin (2004:564–566)), although the classical hypothetical lingers on in cliched phrases. The only exception is nara(ba), which became provisional. In the following table, the examples are given for kaku (書く; 'write'), suru (する; 'do'), da/de aru (だ・である; 'be') and yoi (良い; 'be good').

The idiom tatoeba (例えば; lit. 'if one happens to make a simile', 'for example') was the hypothetical form of the nidan verb tatō (例ふ; 'to make a simile').[443] The phrase sayō nara (左様なら; 'farewell') came from an archaic hypothetical phrase that literally meant "if it happens to be like that".[444][445][446]

Conditional: Advanced usage

In its negative conjugation (〜なければ, -nakereba), the conditional form can express obligation or insistence by attaching to 〜ならない (-naranai, to not happen) or 〜なりません (-narimasen, to not happen (polite)). This pattern of grammar is a double negative which loosely translates to "to avoid that action, will not happen". Semantically cancelling out the negation becomes "to do that action, will happen" ; however the true meaning is "I must do that action".[447][448]

Concessive

In earlier stages of Japanese, the particle -do (ど) was used in place of -ba (ば) for what is known as the concessive, which was used in premodern Edo Japanese.[449] In the modern paradigm, combinations of the gerund and the particle mo (も), or of the infinitive and the particle nagara (ながら), are preferred,[450][451] while the older concessive is used only in cliches or elevated writing.

Politeness stylization

Summarize

Perspective

The auxilaries desu and -masu, and the verb gozaru can be used to enhance politeness. In general, the more verbose forms with -masu and even gozaimasu are more polite.[452][453]

- Desu substitutes de aru and da for more politeness. Desu adds politeness and expresses tense and affirmativity:

- de aru / da → desu ("are")

- Desu makes verbs and adjectives more polite. Desu only adds politeness:

- akai → akai desu ("are red"), akaku nai → akaku nai desu ("aren't red")

- akakatta → akakatta desu ("were red"), akaku nakatta → akaku nakatta desu ("weren't red")

- kaku → kaku desu ("write"), kakanai → kakanai desu ("don't write")

- kaita → kaita desu ("wrote"), kakanakatta → kakanakatta desu ("didn't write")

- nai → nai desu ("don't exist")

- nakatta → nakatta desu ("didn't exist")

- de nai → de nai desu ("aren't")

- de nakatta → de nakatta desu ("weren't")

- Deshita substitutes de atta and datta for more politeness. Deshita adds politeness and expresses tense and affirmativity:

- de atta / datta → deshita ("were")

- Deshita makes past adjectives more polite. Deshita adds politeness and expresses tense and affirmativity:

- akakatta → akai deshita ("were red")

- -Masu makes nonpast affirmative verbs more polite. -Masu adds politeness and expresses tense and affirmativity:

- kaku → kakimasu ("write")

- aru → arimasu ("exist")

- de aru / da → de arimasu ("are")

- -Masen makes nonpast negative verbs more polite. -Masen adds politeness and expresses tense and negativity:

- kakanai → kakimasen ("don't write")

- nai → arimasen ("don't exist")

- de nai → de arimasen ("aren't")

- -Masen deshita makes past negative verbs more polite. -Masen adds politeness and expresses negativity, while deshita maintains politeness and expresses tense:

- akaku nakatta → akaku arimasen deshita ("weren't red")

- kakanakatta → kakimasen deshita ("didn't write")

- nakatta → arimasen deshita ("didn't exist")

- de nakatta → de arimasen deshita ("weren't")

- Adjectives cannot directly combine with -masen, but with arimasen:[ai]

- akaku nai → akaku arimasen ("aren't red")

- akaku nakatta → akaku arimasen deshita ("weren't red")

- -Mashita makes past affirmative verbs more polite. -Mashita adds politeness and expresses tense and affirmativity:

- kaita → kakimashita ("wrote")

- atta → arimashita ("existed")

- de atta / datta → de arimashita ("were")

- Desu can further attach to -masu, -masen, -mashita for even more politeness, but such attachments have been characterized as, "excessively polite", "unrefined" or "ingratiating":[454][202]

- kakimasu → kakimasu desu ("write"), kakimasen → kakimasen desu ("don't write"), kakimashita → kakimashita desu ("wrote")

- Deshō makes nonpast affirmative tentative verbs, and past and nonpast tentative adjectives, more polite. The main verbs/adjectives express tense and affirmativity or negativity, while deshō adds politeness and expresses tentativity:

- akai de arō / akai darō / akakarō → akai deshō ("are probably red")

- akakatta de arō / akakatta darō / akakattarō → akakatta deshō ("were probably red")

- akaku nai de arō / akaku nai darō / akaku nakarō → akaku nai/arimasen deshō ("aren't probably red")

- akaku nakatta de arō / akaku nakatta darō / akaku nakattarō → akaku nakatta deshō ("weren't probably red")

- kaku de arō / kaku darō / kakō → kakimasu/kaku deshō ("probably write")

- kaita de arō / kaita darō / kaitarō → kakimashita/kaita deshō ("probably wrote")

- kakanai de arō / kakanai darō / kakanakarō → kakimasen/kakanai deshō ("probably don't write")

- kakanakatta de arō / kakanakatta darō / kakanakattarō → kakanakatta deshō ("probably didn't write")

- aru de arō / aru darō / arō → arimasu/aru deshō ("probably exist")

- atta de arō / atta darō / attarō → arimashita/atta deshō ("probably existed")

- nai de arō / nai darō / nakarō → arimasen/nai deshō ("probably don't exist")

- nakatta de arō / nakatta darō / nakattarō → nakatta deshō ("probably didn't existed")

- de aru de arō / de aru darō / de arō / darō → deshō / de arimasu deshō ("probably are")

- de atta de arō / de atta darō / de attarō / datta darō / dattarō → de arimashita/atta deshō ("probably were")

- de nai de arō / de nai darō / de nakarō → de arimasen/nai deshō ("probably aren't")

- de nakatta de arō / de nakatta darō / de nakattarō → de nakatta deshō ("probably weren't")

- -Masen deshita deshō makes past negative tentative verbs more polite. -Masen adds politeness and expresses negativity, deshita maintains politeness and expresses tense, while deshō maintains politeness and expresses tentativity:

- akaku nakatta darō / akaku nakattarō → akaku arimasen deshita deshō ("probably weren't red")

- kakanakatta darō / kakanakattarō → kakimasen deshita deshō ("probably didn't write")

- nakatta darō / nakattarō → arimasen deshita deshō ("probably didn't existed")

- de nakatta darō / de nakattarō → de arimasen deshita deshō ("probably weren't")

- Deshitarō can substitute deshita deshō, and -mashitarō can substitute -mashita deshō, although both are uncommon.

- -Mashō makes nonpast affirmative tentative/hortative verbs more polite. Whether the verb is tentative or hortative is contextual, but verbs with human agency tend to be hortative, and those without tend to be tentative. -Mashō adds politeness, and expresses tense, affirmativity and tentativity/hortativity:

- kakō → kakimashō ("probably write; want to write; let's write")

- kumorō → kumorimashō ("it's probably cloudy")

- arō → arimashō ("probably exist")

- de arō / darō → de arimashō ("probably are")

- Gozaimasu substitutes or appends to -masu, arimasu and desu for even more politeness. Extra instances of desu, deshita and deshō can be added to make up for missing forms. The negative and past forms can be based on the original verb/adjective, or based on gozaimasu, or supplied with deshita:

- Nonpast affirmatives:

- akai desu → akō gozaimasu ("are red"), akai deshō → akō gozaimashō ("are probably red")

- kakimasu / kaku desu → kaku (no) de gozaimasu / kakimasu de gozaimasu ("write"), kakimasu/kaku deshō / kakimashō → kaku (no) de gozaimashō / kakimasu de gozaimashō ("probably write")

- arimasu / aru desu → gozaimasu ("exist"), arimasu/aru deshō / arimashō → gozaimashō ("probably exist")

- desu / de arimasu → de gozaimasu ("are"), deshō / de arimasu/aru deshō / de arimashō → de gozaimashō ("probably are")

- Nonpast negatives based on gozaimasen:

- akaku nai desu / akaku arimasen → akaku/akō gozaimasen ("aren't red"), akaku nai/arimasen deshō → akaku/akō gozaimasen deshō ("aren't probably red")

- kakimasen / kakanai desu → kaku (no) de gozaimasen / kakimasu de gozaimasen ("don't write"), kakimasen/kakanai deshō → kaku (no) de gozaimasen deshō / kakimasu de gozaimasen deshō ("probably don't write")

- arimasen / nai desu → gozaimasen ("don't exist"), arimasen/nai deshō → gozaimasen deshō ("probably don't exist")

- de arimasen / de nai desu → de gozaimasen ("aren't"), de arimasen/nai deshō → de gozaimasen deshō ("probably are")

- Nonpast negatives based on the main verbs:

- kakimasen / kakanai desu → kakanai (no) de gozaimasu / kakimasen de gozaimasu ("don't write"), kakimasen/kakanai deshō → kakanai (no) de gozaimashō / kakimasen de gozaimashō ("probably don't write")

- Past affirmatives based on gozaimashita:

- akakatta desu / akai deshita → akō gozaimashita ("were red"), akakatta deshō → akō gozaimashita deshō ("were probably red")

- kakimashita / kaita desu → kaku (no) de gozaimashita ("wrote"), kakimashita/kaita deshō → kaku (no) de gozaimashita deshō ("probably wrote")

- arimashita / atta desu → gozaimashita ("existed"), arimashita/atta deshō → gozaimashita deshō ("probably existed")

- deshita / de arimashita → de gozaimashita ("were"), deshita deshō / de arimashita/atta deshō → de gozaimashita deshō ("probably were")

- Past affirmatives based on the main verbs/adjectives:

- akakatta desu / akai deshita → akakatta de gozaimasu ("were red"), akakatta deshō → akakatta de gozaimashō ("were probably red")

- kakimashita / kaita desu → kaita (no) de gozaimasu ("wrote"), kakimashita/kaita deshō → kaita (no) de gozaimashō ("probably wrote")

- Past negatives based on gozaimasen deshita:

- akaku nakatta desu / akaku arimasen deshita → akaku/akō gozaimasen deshita ("weren't red"), akaku nakatta/arimasen deshō → akaku/akō gozaimasen deshita deshō ("were probably red")

- kakimasen deshita / kakanakatta desu → kaku (no) de gozaimasen deshita ("didn't write"), kakimasen deshita deshō / kakanakatta deshō → kaku (no) de gozaimasen deshita deshō ("probably didn't write")

- arimasen deshita / nakatta desu → gozaimasen deshita ("didn't exist"), arimasen deshita deshō / nakatta deshō → gozaimasen deshita deshō ("probably didn't exist")

- de arimasen deshita / de nakatta desu → de gozaimasen deshita ("weren't"), de arimasen deshita deshō / de nakatta deshō → de gozaimasen deshita deshō ("probably weren't")

- Past negatives based on the main verbs/adjectives:

- akaku nakatta desu / akaku arimasen deshita → akaku nakatta de gozaimasu ("weren't red"), akaku nakatta/arimasen deshō → akaku nakatta de gozaimashō ("were probably red")

- kakimasen deshita / kakanakatta desu → kakanakatta (no) de gozaimasu ("didn't write"), kakimasen deshita deshō / kakanakatta deshō → kakanakatta (no) de gozaimashō ("probably didn't write")

- Nonpast affirmatives:

- Gozaimasu deshō can substitute gozaimashō.

In principle, desu, de arimasu and de gozaimasu can be mere politeness enhancers and can attach to anything, even in such cases as -masu desu, -mashita desu, -masu de gozaimasu[452] or (de) gozaimasu de gozaimasu.[455][456][457]

See also

Notes

- When spelt in hiragana, the standard spelling is still いう, not *ゆう.[17][18] This convention, along with the particles wa (は), e (へ) and o (を), is retained from historical kana orthography for practical purposes. For yū (言う), the kana spelling いう is in keeping with other conjugational forms such as iwanai (いわない) and itta (いった). 言う (yū, 'say') is possibly homophonous with 結う (yuu → yū, 'fasten'),[19] except that the latter can be unaccented or accented, while the former is only unaccented.[20][21] In this article, the more phonetically accurate spelling ゆう is used in the conjugation tables below not to obscure phonetic changes between verb forms.

- The mizenkei base for verbs ending in ‑u (〜う) appears to be an exceptional case with the unexpected ‑wa (〜わ). This realization of ‑wa is a leftover from past sound changes, an artifact preserved from the archaic Japanese ‑fu from ‑pu verbs (which would have yielded, regularly, ‑wa from ‑fa from ‑pa). This is noted with historical kana orthography in dictionaries; for example, yū (言う) from ifu (言ふ) from ipu and iwanu (言わぬ) from ifanu (言はぬ) (from ipanu).[25] In modern Japanese, original instances of mid‑word consonant [w] have since been dropped before all vowels except [a].[25][26][27] (For more on this shift in consonants, see Old Japanese § Consonants, Early Middle Japanese § Consonants, and Late Middle Japanese § /h/ and /p/). Yuwa‑ is quite common among a number of actors.[22]

- Suru and many (but not all) of its compounds currently do not accept potential forms, but rely on the circumlocutory (koto ga) dekiru instead.

- For verbs like kau (買う; 'buy'), yū (言う; 'say'), etc, there is a clear preference for sokuonbin in northern and eastern dialects, as in katte (買って), itte/yutte (言って) (with yutte being less common generally or by individual speakers who have used both[22]); and for u‑onbin in western and southern dialects, as in kōte (買うて), yūte (言うて).[31][32] However, according to two surveys conducted in 2016 and 2017, at least some speakers, particularly female college students from Notre Dame Seishin University, from the western prefecture of Okayama, showed a strong preference for itta n/yutta n (言ったん), even though the broader public still preferred yūta n, and there was a discreprancy in preference for the said forms and itta no/yutta no/yūta no (言ったの).[22]

- Historically not distinguished from the passive.

- Ja/jatta/jaro rather than da/datta/daro, tōsan(u) rather than tōsanai, etc.

- Tōku rather than toō, oyobanakatta rather than oyobananda, nigero rather than nigē, etc.

- Some traditional descriptions also count dat in datta ("was/were"), which was historically de arita, as well as deshi in deshita.

- For more specific derivatives, see mentions of aru (ある) in the following sections.

- No longer audible on the surface level as it fused with the conjectural auxiliary -u to make the form below. Historically still spelt out in modern literature before spelling reform, as in だらう, though the actual pronunciation was still darō.

- Historically also spelt ぢやら or じやら before spelling reform.

- Only audible in the negative de (wa) arimasen(u) shown above. When combining with the conjectural auxiliary -u, it became the form shown below. Historically still spelt out in modern literature before spelling reform, as in ませう, though the actual pronunciation was still mashō.

- No longer audible on the surface level as it fused with the conjectural auxiliary -u to make the form below. Historically still spelt out in modern literature before spelling reform, as in でせう, though the actual pronunciation was still deshō.

- Etymologically only. Currently, instances of ni (wa) aru do not involve the copular ni, but the locative ni, meaning A ni aru actually means "that is in A" rather than "that is A".

- Etymologically only.

- These lines are spoken by a character from Kagoshima Prefecture.

- Equivalent to -nai darō/deshō, -masen desō, among others.

- Or, "It's conduct that shouldn't be for a student."

- Or, "There must not be no word (=there must be a word) against his action."

- Or, "it's impossible to count his exploits."

- Or, "the list of what not to do"

- Or, "There are things inexplicable by human knowledge."

- A quote attributed to Steve Jobs.

- Compare the alternative forms of joi/ii (良い), yuku/iku (行く).

- This verb is primarily godan, therefore the more common imperative is actually kere.

- The author argues that the imperative forms of most verbs are inherently rude in speech, barring those of honorific verbs which are presumed to be polite, such as irasshai (いらっしゃい; 'come, please!'), asobase (遊ばせ; 'let do/be, please!'), kudasai (下さい; 'give me, please!'). The problem is that, with the sole exception of goranjiro (御覧じろ; 'look, please!'), most of these verbs' conjugations (yodan/godan) have nothing to do with ‑ro (non-yodan/godan only), giving ‑ro an unavoidable connotation of rudeness. ‑Yo, on the other hand, is associated with classical Japanese (the "written" language) and therefore is the only appropriate option in formal contexts, even in speech.

- In some cases, there may be ambiguity. Compare yoku nai desu (よくないです; 'aren't good') and yoku arimasen (よくありません; 'aren't common; aren't good (?)').

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads